By DOUGLAS KANE, TONY LICATA and DUANE W. WAUGH

The three authors were asked to submit separate articles on bonding; the

background material is a composite of all

three manuscripts, but their opinions on the

state's use of bonding are attributed to the

individual author.

DOUGLAS KANE

A Democratic state representative of the

50th district (Montgomery and Sangamon

Counties), he holds the Ph.D. degree in

public finance from the University of

Illinois and serves on the House Revenue,

Higher Education, and Appropriations I

Committees.

TONY LICATA

A program analyst for the Illinois Capital

Development Board, he has also been an

administrative assistant in the

Governor's Action Office and a reporter

for the DuQuoin Evening Call.

He will enter Harvard Law

School in September.

DUANE W. WAUGH

Currently working as a budget analyst for

the Illinois Bureau of the Budget, he

holds a master's degree in business

administration from the University of

Chicago.

MOST PEOPLE would agree that it is imprudent to take out a three-year loan to pay this month's grocery bill. The food consumed this month will have lost its value entirely by next month. And finance companies are not in the habit of making long-term grocery loans. Conversely, most people would find it extremely prudent to take out a 20-year or 30-year loan to buy a house. After 30 years the house still has value and still provides benefits to the owner. We can connect these examples and say, metaphorically, that the State of Illinois borrows money to build houses, but not to buy groceries. The term that describes this borrowing process is bonding. The near default of New York City on its debts recently has brought bonding into the public eye nationwide, but in Illinois the practice has been a major political issue in every session of the General Assembly since the new Illinois Constitution went into effect July 1, 1971. Under the new Constitution, the issuing of general obligation bonds is much easier, requiring only a three-fifths vote of both House and Senate. Under the 1870 Constitution, approval by a statewide referendum was required.

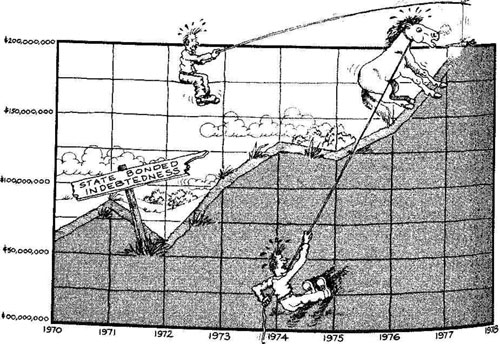

Bonding increase

In the four years following 1971, the

actual general obligation bonded debt

of Illinois increased almost three times,

jumping from $339.3 million as of June

1971 to $969.2 million in June 1975. The

pace at which debt has been authorized

has also accelerated, although much of

this bonding authority is unused.

During the last 20 years under the old

Constitution, $1.48 billion in general

obligation debt was authorized by referendum

$385 million to pay veterans' bonuses; $345 million

for mental health and higher education buildings, and

$750 million for sewage treatment plants (anti-pollution bonds).

In just the first four years (1971-75) under the new Constitution, almost $2.4 billion in general obligation debt was authorized by the legislature. A little more than half of that sum was earmarked for highways and mass transportation facilities. Much of the rest of it is going for educational buildings, but all kinds of projects are included.

In addition, as part of his fiscal 1976 budget Gov. Dan Walker asked for $761 mil lion in new general obligation bonding authority, of which $152.2 million was approved. From I960 to February 1976, a total of $3,492.2 million worth of borrowing had been authorized. Of that amount, the state through May 30 has already drawn down $1,655 million, and has paid back $285.5 million. So what it boils down to is this: the state currently owes $1,369.5 million and can, as its leaders see fit borrow another $1,837.2 million on the current authorizations.

These enormous sums have raised the question of whether the state is abandoning its conservative borrowing practices and taking on burdensome debt commitments. How do legislators and other state officials weigh the financial merits of employing debt in preference to pay-as-you-go financing from current tax revenues? Behind this question is the abiding belief that borrowing money must eventually lead to higher taxes.

Widely acceptable guidelines for determining capital spending levels are difficult to establish. It is possible, however, to put together enough facts to allow decision makers to reach more informed judgments about financing capital construction. If we know the relative as well as the absolute size of bond-financing activities in Illinois, and of the characteristics and purposes of the projects being financed, we may gain a useful perspective on the role of debt in the state budget.

Borrowing too much?

Simply put, the issue is this: Is Illinois

borrowing too much to pay for long-

term capital improvements such as

schools, hospitals, parks, highways and

university facilities? The question is

important since borrowed money must

be paid back sometime. Will future

taxpayers find a greater portion of their

General Fund outlays paying for decisions

made years earlier? Furthermore,

the availability of borrowed funds

enhances the attractiveness of what

might be labeled "pork barrel" projects.

Since a legislator can vote for a state

park project knowing that he can claim

18/ July 1976/ Illinois Issues

New Constitution gives General Assembly power to authorize general obligation bonds. Will state maintain its prudent fiscal policy with this new funding flexibility?

credit for it today but will not have to worry about paying the bill until tomorrow, he may be inclined to support frivolous projects outside normal program requirements.

Pressure to use

Finally, a high level of capital expenditures financed from borrowed

funds creates pressure upon governmental decision makers both in the

legislative and executive branches to

approve an ever growing number of

projects. How does a policymaker set

priorities among requests for capital

outlays when it's all borrowed money? If

the state can borrow for Western Illinois

University's new library, then why not

borrow to construct a law school at

Southern Illinois University?

The state borrows by selling bonds that is, in return for hard cash it issues a certificate promising to repay the amount of the loan and a specified rate of interest. There are two types of bonds: revenue and general obligation. Revenue bonds, which are mainly repaid from user's fees and do not draw upon General Revenue Funds, are discussed further on in the article. It is the general obligation bond backed by the "full faith and credit" of the state taxpayers that directly affects the state's budget. There are also special cases when state funds pay the debt of revenue bonds.

Under old Constitution

Prior to the adoption of the 1970

Constitution, Illinois struggled with the

strict financing provisions of the 1870

Constitution, which required a state-

wide referendum to incur general

obligation debt. In 1870 memories of

widespread default on public securities

resulting from the Jacksonian depression

were painfully fresh. All of the

various bonding authorities established

previous to 1971 were efforts to

circumvent the 1870 Constitution's rigid

policy. The need to borrow money more

easily for the financing of capital

projects was a definite factor

in producing the 1970 Constitution.

Since 1870 the state of Illinois has been either free of debt or so concerned about the amount of its indebtedness that default has not even been a remote possibility. This relatively low debt burden has been a factor in the state's excellent credit rating of triple-A by two private bond rating agencies, Standard & Poor's Corporation and Moody's Investors Service, Inc. The rating is the best that any borrower can achieve, and the effect of such a rating is to allow the state to borrow at the lowest interest cost that can generally be obtained in the municipal market. In Illinois' recent history, interest rates have been below six per cent for money borrowed through general obligation bonds.

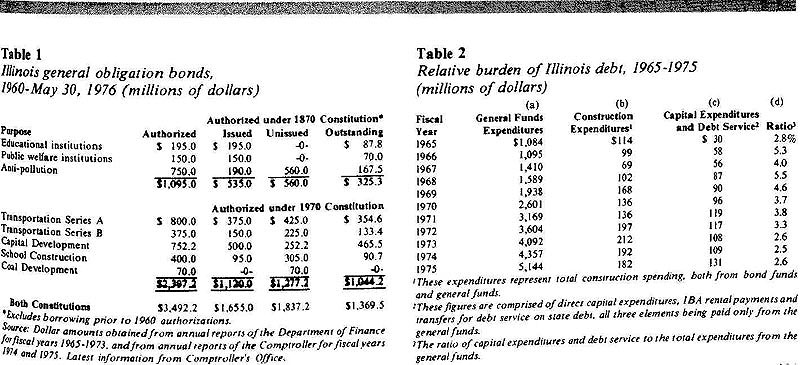

Since new Constitution

The bond issues passed under the new

Constitution plus those previously

authorized by referendum are as follows

(see Table 1 for amounts authorized and

issued):

1. Anti-Pollution Bonds to furnish funds to construct municipal sewage treatment plants and solid waste disposal facilities (authorized by referendum under the 1870 Constitution).

2. Capital Development Bonds are authorized in specific amounts for specific purposes: $482.5 million for higher education, $11 million for corrections, $103 million for conservation, $77.6 million for child care, mental health and public health, $120.5 million for general state purposes, $6 million for regional port districts, $ 12.5 million for water resources projects, and $10 million for education purposes for nonprofit, non-public health service organizations. The total of these bonds is $823.1 million, but only $752.2 million may be issued according to the statute.

3. Coal Development Bonds are designed to encourage development of Illinois' coal reserve by federal and private investors.

4. Educational Institutions Bonds are for higher education (authorized under the 1870 Constitution, this bonding authorization is exhausted).

5. Mental Health and Public Welfare Institutions Bonds are for construction of mental health treatment and other welfare service facilities (authorized under the old Constitution, this bonding authority is exhausted).

6. School Construction Bonds are used to finance state grants to local school districts for construction or renovation of school facilities. These funds are also used to assist local districts with debt service on their bond issues.

7. Transportation Series A Bonds are for highway construction.

8. Transportation Series B Bonds are for mass transit and airports. (Transportation Series A Bonds are retired from payments from the Road Fund, and thus, any growth in borrowing which affects the General Revenue Fund will occur in the other programs).

Revenue bonds

Revenue bonds finance projects

which pay for themselves through fees

charged to those who use the facilities.

No appropriation of state funds is

required to pay principal or interest on

revenue bonds, but there are exceptions.

Four agencies which have issued

revenue bonds receive state funds, as a result

of statute or contractual agreement.

State taxpayers are still paying for

projects constructed by the Illinois

Building Authority (IBA), the Illinois

Armory Board, the Metropolitan Fair

July 1976/ Illinois Issues/ 19

At present, Illinois has a low debt/income ratio a significant measure of the state's ability to pay off its debts. Bonding priorities have been for education and highway construction

and Exposition Authority (which built McCormick Place in Chicago), and the Springfield Metropolitan Exposition and Auditorium Authority. The primary example of these agencies is the IBA which between 1964 and 1972 issued $543 million worth of revenue bonds that were used to finance higher education, mental health, conservation and correctional facilities. These bonds are now being paid off with "rental payments" to the IBA from the state's general revenue funds.

Education, highways

The state's current capital program

financed by general obligation bonds is

shown in Table 1. Approximately one-

third or nearly $1.1 billion of the total

bonding authorizations is for education

(elementary, secondary and higher

education), and represents 40 percent of

all bonds payable from the General

Revenue Fund. The next largest use for

bonds is highways $800 million in

authorization or about 23 per cent of the

total. The $750 million for pollution

control purposes accounts for 21 per

cent of total authorization.

These bond authorizations reflect a financial commitment by the state for particular kinds of investment in buildings, roads, etc. We may presume that these authorizations are evidence of the demand or need for public services or facilities, since they were determined through majority action by the legislature and approved by the governor (and in some cases by the voters through referendum). For all of these capital programs, the authorization does not specify a time period within which the amount of authorization should be fully expended.

Of the $1.6 billion issued in general obligation bonds since 1960, about one- third has been for education and about 20 per cent of the total has been issued for highways. Thus, education and high- way construction account for more than half of all general obligation debt incurred by the state in the past 15 years.

These percentages are not surprising. Aggregate state expenditures for education in fiscal year 1975 accounted for 43 per cent of all spending from the General Revenue Fund and Common School Fund. Similarly, appropriations from all highway funds in fiscal year 1975 amounted to 15 per cent of total state appropriations for that year. The point is that authorization and use of debt financing reflects generally the relative priority given to education and highways in the state budget as a whole.

Gov. Walker's fiscal year 1977 budget book argues that the state's indebtedness is reasonable and is maintained at a sound level. The budget document points out that five major states (New York, Pennsylvania, California, Massachusetts and Ohio) have more aggregate debt than Illinois. Illinois ranks low on the list of major industrial states when the state debt is compared to personal income of Illinois residents. Among the same states, only California has a lower debt per capita. As the budget book points out, "The ratio of debt to total income is significant as a measure of the state's ultimate ability to raise the funds required to meet debt service payments." State governments, like private individuals, must expect to have their debt/income ratio scrutinized by lending institutions before new loans are approved.

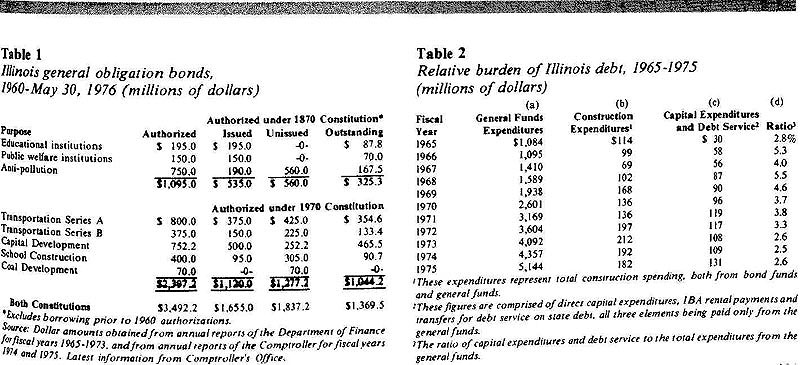

Debt service

What proportion of general fund

revenues goes for permanent

improvements? In fiscal year 1975 the percentage

of total general funds expenditures

attributable to financing capital

construction was lower than for most of the

past 10 years. In none of these years

could the burden of carrying state debt

be considered as a large or dominant

part of the state budget. Obviously, the

adoption of the state income tax in 1969,

which substantially increased the state's

resources in fiscal year 1970 and there-

after, may account for the reduced ratio

of capital expenditures and debt service

to total expenditures in 1970. Yet,

without any further change in the tax

structure, after 1969, the ratio continued

to decline through fiscal year 1974

before rising slightly in 1975.

Considering fiscal year 1975 only, even if we

eliminate income tax revenues ($1,580

million) from total spending for that

year, the ratio of capital expenditures

and debt service ($141 million) to the

remaining expenditures ($3,564 million)

rises to 3.7 per cent, still below the ratio

in the late sixties.

Debt and state budget

How does debt affect the state's

budget? Table 2 covers fiscal years 1965

through 1975, and compares total

spending of general revenue funds to

total capital expenditures and debt

service paid from the general funds for

the last 11 years.

The general funds expenditures in Table 2 include the total demand - direct expenditures and transfers to other state funds, including financing the state debt made on the general funds.

The construction expenditures given in column (b) consist of (1) funds derived from the sale of bonds ( including funds derived through the sale of revenue bonds of the Illinois Building Authority), and (2) spending of current tax revenues directly from the general funds. The IBA initiated $543.4 million of bond-financed construction between 1964 and 1972 on behalf of the State of Illinois, and the state is paying the full amount of debt service due on those bonds. The state leases the capital facilities from the IBA, pays rent as called for in the leases, and the IBA in turn pays debt service on its revenue bonds from the rent. When those bonds are paid in full, the facilities constructed become the property of the state. To exclude the IBA debt from this analysis would be to substantially understate the amount of capital spending which the state has authorized on its behalf during the past decade.

To finance the state's capital construction (column (c)), three specific demands are made on the general funds:

(1) direct capital expenditures, (2) IBA rental payments and (3) transfers from the general funds to the debt service funds to pay principal and interest on the state's general obligation bonds.

The individual analysis of general obligation bonding follows in separate sections by the authors.

20/ July 1976/ Illinois Issues

Licata:

Industries should

not depend too

much on state bonds

As the percentage of General Revenue Fund expenditures devoted to debt service and higher operating costs resulting from the capital investments increases, the amounts available for other programs are restricted. A large growth in debt payments and associated operating costs might possibly devour increases in general revenue. If future revenue growth must be increasingly allocated to higher capital investment costs, there will be fewer dollars available for increases in education or public aid. In short, too much bonded debt will make a tax increase inevitable.

As the state builds public facilities, it creates a demand for capital goods, thereby stimulating private investment in the means of producing those goods. Labor will become accustomed to finding work at state-financed projects. And bureaucrats will come to expect new facilities on a regular basis. What happens when all the borrowed money is spent? Most likely, contractors, labor and bureaucrats will join in demanding that the state issue new bonds in order to maintain high levels of capital construction. A condition might well result whereby the state must continually borrow to maintain high employment and prosperity in its capital goods industries. A continual expansion of the debt to be serviced would only aggravate the problems described above.

This in fact is the real danger of annual high levels of capital expenditures financed through borrowing. Illinois may well be creating a situation not unlike that of the so-called "military-industrial complex" in which a whole industry has become dependent upon government spending for survival. Just as Lockheed and the Pentagon lobby vigorously for continual increases in defense spending, so too may private firms and state agencies come to lobby for ever more capital outlays.

Such speculation may be carrying things too far. It must be granted that there are benefits to debt financing. Borrowing allows for the immediate construction of urgently needed facilities, whereas paying for such items from current revenues would create delays. And debt service payments extended over a long period of time allow future taxpayers who use the facilities to share in the cost of providing them.

The proposed total capital appropriation for fiscal 1977 in the governor's March budget book is $608.7 million, which is substantially below the $830.2 million approved in fiscal 1976. This reduced level of investments indicates a determination not to allow debt- financed expenditures to run rampant. Rumblings from various quarters, however, indicate that there is much dissatisfaction with the proposed level of capital outlays, and that the legislature may be pressured to approve higher levels of spending.

Please turn to next page for Kane and Waugh opinion.

July 1976/ Illinois Issues/ 21

Kane:

Decide merits of a

project first

then the financing

Gov. Walker, in urging the passage of his $4.1 billion bonding program to the legislature last year, gave these reasons:

(1) in a time of recession when tax revenues are down, the state has the "obligation" to use bond financing for capital projects "to fight the recession;"

(2) bond-financed projects will create jobs; (3) bonds will give us money to build projects now before inflation drives construction prices up, and (4) bonding will allow projects to be paid for as they are being used and by the people who are benefiting from them.

Walker's general position, in other words, was that in times of recession government should create additional demand in order to put idle resources to work. The secondary arguments have to do with timing to take advantage of price, and intergenerational equity the idea that each generation which obtains some use or benefit from a capital project should pay a portion of the cost.

The arguments against heavy bonding are basically those of fiscal prudence: the state should live within its means; it should not incur unnecessary debt; interest almost doubles the cost of a project; bond financing is too easy and encourages projects that would not be undertaken if finances had to be secured through current taxes, and that bonds must be authorized only after consideration of the long-range effect on the state budget. Taxes will have to be raised if the state issues too many bonds. Bonds, after all, must eventually be repaid, and with interest.

General considerations of fiscal prudence aside, the argument that periods of recession, inflation and unemployment are the most opportune for bond-financed capital construction is open to other, more specific criticisms. Bonded construction projects normally take too long in their startup to have any beneficial effect on the slack economy that existed at the time the bonds were authorized. Several large construction projects can help turn around recession in an area, but such projects normally take two to four years of actual construction, and it may take two years of planning, engineering, etc.. before construction actually begins. Economic cycles are usually of shorter duration, so there is a good chance that actual construction will take place during the succeeding upturn in the economy, thereby reinforcing the cycli- cal swing rather than dampening it.

Capital projects may have a major effect on the construction industry, but the effect on the rest of the economy is indirect and more limited. If the con- struction industry is in particularly bad shape, capital projects may be desirable, but when Walker proposed his bonding program last year, only a small part of the state's unemployment was in con- struction. Most unemployment at that time was in manufacturing and finance. Also, a massive public building program may bid resources away from the private sector competing for private invest- ment funds and driving up prices. The effect of this is to transfer resources from the private to the public sector at a higher cost.

Proponents of bond ing say, "Let's build now before prices rise even further." But this is simplistic. Prices are related to capacity, supply and demand. If the construction industry is already near capacity, and building costs are undergoing rapid inflation, additional demand will only result in further price increases and no additional output. These are good reasons for government to postpone construction in periods of rapid inflation. When demand drops prices Will tend to level off.

The problem of construction capacity could become critical in the next few years. For example, several billion dollars of federal, state and local money will go to build sewage treatment plants in Illinois in the next five to seven years Right now the strain is on the engineering profession. Two Illinois firms have more than 100 sewage treatment projects between them, and delays are developing. When actual construction begins on these projects, there is a real question whether the construction industry in the state can handle the volume and maintain reasonable prices.

But this question of intergenerational equity is not straightforward. The real costs of a capital project for the bricks, the mortar, the cement, the use of construction equipment, the labor, the money must be paid for at the time of construction. If the projects are financed with borrowed money (bonds) rather than tax money, when the money is paid back in the future, it will be transferred from the taxpayer's pocket to the bondholder's pocket with no net burden in total economy.

The bond market itself imposes certain limits on bond financing by states and other public bodies. The net supply of new credit in the American economy in the last four years has fluctuated in the neighborhood of $175 billion. That sum must finance new federal debt, corporate borrowings,

22/ July 1976/ Illinois Issues

business loans, mortgages, consumer loans as well as state and local government bonds. Net new issues of state and local government bonds represent only a small part of the market, averaging $15 billion per year during the past four years. It is in this rather limited money market that Illinois must compete Bond experts tend to agree that under the most favorable conditions $600 million is the upper limit of bonds that any single unit of government (other than federal) can sell in a year. In addition, states shouldn't go to the market more often than once every three months. Few states have embarked on that massive a program, and the credit ratings of those that have done so have been adversely affected. The more debt any government piles up, the less attractive its bonds are to prospective purchasers and the higher the interest rates that must be paid to attract purchasers.

In calendar 1975 the state administration planned to market in the neighborhood of $600 million in bonds. Only $300 million was sold in 1975; however, another $150 million was sold in the spring of 1976. Because of the cash flow "crisis" during the fall of 1975, the attractiveness of Illinois bonds in the future may be decreased. The bond market has a long memory. In Moody's rating of Illinois' credit, mention is made of the stated default on bond interest payments in July 1841 caused by numerous bank failures during the recession of that period.

It is difficult to set general guidelines for the evaluation of bonding programs. Often it is a matter of judgment, and the judgments of the officials charged with making decisions can vary. It should be remembered, however, that bonding is a financing mechanism. The merits of projects to be financed should be determined first. Only after a project is deemed worthy, should the question of the best means of financing that project be raised.

The more "lumpy" the state's conduction program, the more sense bonds make as a financing vehicle. That is, if a state projects a heavy construction schedule for four or five years which will then drop off sharply, bonding would allow payments to be spread over a 20-to-30-year period, thus avoiding sharp dislocations in the tax structure. The price one pays for this, of course, is the interest. If a state projects a relatively even flow of construction over a period of 15 to 20 years, it makes more sense to finance that construction out of current revenue. The even flow does not put an undue burden on the tax structure, and the interest costs are saved. Whether these savings outweigh the inflated construction costs for future projects is extraordinarily difficult to determine.

Illinois has embarked on a heavy bonding program since the new Constitution has gone into effect. Passage by the legislature has been relatively easy, although resistance to new issues seems to be building.

If the state is faced with a need to trim expenditures, capital construction is no less and no more an appropriate budget element to examine than is any other element in the budget. But insofar as the outlays associated with that item account for 2.6 per cent of total outlays, the hoped for savings must be regarded as marginal. Other areas of the budget command far larger shares of total resources and must be examined at least as resolutely as capital financing.

Where there is impetus to curtail the use of state debt, ostensibly to keep the state from getting into too much debt or to reduce any pressure for increased tax revenues, the implications of a new financial policy must be acknowledged. To maintain and pay for existing capital programs from current tax revenues requires (given the financial leverage that accompanies bond financing), that for each dollar of additional debt service that is to be avoided in future budgets, more than one dollar of spending must be cut from those budgets (in non- capital areas). Or, if new revenues are to be raised, more than one dollar of additional revenue must be raised for each dollar of debt service to be avoided. To reduce the stated reliance on debt as a tool of capital financing would exacerbate the problem of making budget cuts in non-capital areas or intensify the need for additional revenues. Otherwise, the capital programs themselves must be sharply curtailed.

Finally, the state can borrow only so much in order to save money by building sooner than later, and those projects which the state borrows to undertake must be the ones which will bring the greatest benefits. The analogy of the family budget is again instructive. Obviously, a family can save money by anticipating what it will need in the future and buying before prices rise. So, a family may borrow money to purchase a new car, a washing machine, furniture, a second bathroom but not groceries in order to "beat" inflation. But few families can afford to purchase all these items at once.

The point is that only so much of any budget, family or state government, can be put into long-term purchases. And the long-term purchases selected must be not only the ones that the greatest saving can be realized on, but the ones that are needed most now and in the future. The fact that washing machines are selling at a good price does not mean that a family will go out and buy two. Nor will a state government build all the bridges it can across the entire state simply because construction costs are low at a particular time. Clearly, families and state governments will always desire to borrow in order to purchase needed items at lower prices, but what they buy depends on how much they can afford to borrow and how much they need the particular purchase. As prices and income fluctuate , as needs change and benefits shift, the long-term items selected by any purchasing unit will also change. As a family grows, it may indeed decide it is wise to purchase two washing machines, and a state government may opt for the construction of several new bridges to replace old bridges that are not adequate for projected use. State government bonding, like family borrowing, will always depend on prudent decision making based on costs, benefits and the upward spiral of the inflationary curve.

July 1976/ Illinois Issues/ 23