By PETER F. NARDULLI An assistant professor of political science and a member of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois, he holds a law degree and aPh.D. from Northwestern University. This article is based on research for a book he is writing on Chicago's criminal justice system.

Criminal justice reform in Cook

County courts: Is more always better?

In 1975 the

Chicago Bar Association

recommended reducing

workloads of trial judges

in the felony court system,

and the 79th General

Assembly did increase the

number of circuit judges in

the state by one-third.

However, comparison of

Cook County court

statistics of 1926 and 1972

indicates that an increase

in resources

will not automatically

create more efficient courts

SINCE THE turn of the century lawyers, litigants, defendants, journalists and scholars have made complaints about the way their local criminal justice system operated. Among the many proposals these complaints have generated, one of the most frequently voiced is to beef up the resources devoted to handling of criminal cases. This was one of the more fundamental proposals of the Wickersham Commission in 1931 and the President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Criminal Justice in 1967.

In Illinois, the Chicago Bar Association in its 1975 Program For Action advocated a major set of reforms for the criminal justice system in Cook County. Underlying this set of reforms, is a call for vast increases in resources — more judges, prosecutors, public defenders, courtrooms, and so forth — allocated to the felony court system. One specific recommendation is to reduce trial judges' workloads from the present rate of approximately 300 cases per year to only 75 cases per year. In response to the recommendation, as well as other factors, the Illinois legislature recently amended the Circuit Judges Act (Illinois Revised Statutes, ch. 37, sec. 72.2) by increasing the number of circuit judges in the state by one-third. Cook County alone will get an additional 30 circuit judges, and Chief Judge John Boyle is quoted as saying that he will assign all 30 to the Criminal Division ( Chicago Sun- Times, November 29, 1975).

While the bar association's proposals and the Illinois legislature's action are clearly within the mainstream of traditional thought on criminal justice reform, until just recently the relationship between criminal justice resources and the "output" of criminal courts has never been examined. Modem criminal justice scholars have begun to look with a wary eye, however, upon reform proposals aimed at increasing resources which are unaccompanied by a more fundamental restructuring of the whole court process. Some researchers have found that substantial increases in criminal justice resources in various court systems have not led to improvements in the efficiency of the courts.

The relationship between increased judicial resources and criminal court output needs to be examined more closely in the Cook County system. Judicial resources can be considered separately and systematically because reliable data exist. Data on the other resources (prosecutors, public defenders, clerks, courtrooms, etc.) are hard to acquire. Also, the level of judicial resources is a good indicator of the level of total criminal justice resources at any given time. More judges means that there must also be more courtrooms, more clerks, more bailiffs, etc., and usually means an increase in the number of prosecutors. A final reason for focusing upon judicial resources is that such an analysis can shed some light upon the impact in Cook County of the recent amendment to the Circuit Judges Act.

There are three generally accepted measures of criminal court output: the conviction rate, the dismissal rate, and the average amount of time required to dispose of a case. These are the most important indicators of courtroom efficiency because they cover the total percentage of defendants convicted, the total percentage arrested but never brought to trial (convictions + dismissals+ acquittals after a trial = total dispositions), and the time required to dispense justice. These three measures are not, of course, perfect indicators of criminal court efficiency because there are no absolute standards by which a court can be gauged. People generally

August 1976 / Illinois Issues/ 5

Lower workloads in 1972 for criminal court judges did not increase the conviction rate, and an average case took about twice as long to process

agree that "criminal justice delayed is criminal justice denied," but ideas of what undue delay means can vary significantly. Finally, the rates of conviction and dismissal depend upon what kind of cases a court handles.

Despite the problems with the measures of efficiency, those who favor increased resources argue that present conviction and dismissal rates are poor, and that processing time is slow. Their position is based upon the belief that many culpable defendants are able to escape from the system because the judges, prosecutors and clerks responsible for processing their cases are overworked and may not get a conviction because they don't have enough time to adequately handle each case. Heavy workloads also produce lengthy and unfair delays in the processing of cases. This affects conviction rates because it discourages witnesses and victims from following through with their initial complaints. Many cases are dismissed for this reason. It is argued that reduced workloads will shorten the time span for all trials, hence producing more convictions in a shorter time and encouraging more initial complaints to be brought to trial.

Although it is impossible to objectively determine whether any culpable defendants are in fact escaping punishment in Cook County, the Cook County felony courts have had historically lower conviction rates than other large urban systems. The Wickersham Report (Vol.4, pp. 190-191), for instance, found that in 1926 only 19.7 per cent of all defendants arrested for felonies in Cook County were convicted. The comparable figure for Milwaukee in 1926 was 63.5 per cent; for Baltimore in 1928, the figure was 53.4 per cent. Similar results were reported in a 1972 study, as yet unpublished, by Herbert Jacob of Northwestern University and James Eisenstein of Pennsylvania State University which compared the felony court systems of Chicago, Baltimore and Detroit. They found that only about 20 per cent of the defendants in Cook County were ultimately convicted — as opposed to 43 per cent in Baltimore and 58 per cent in Detroit. On the basis of these figures, it appears that either the various law enforcement agencies in Cook County are arresting too many innocent people or that at least some guilty defendants are escaping punishment in Cook County.

Cooperative relations

Although there may well be room for

improvement in Cook County, there is

doubt that merely increasing criminal

justice resources will result in improved

conviction rates, dismissal rates and

processing time. Those who advocate

this type of reform fail to recognize that

modern criminal courts do not operate

the way they do on Perry Mason or

Petrocelli. In reality, many judges do

not operate as neutral parties and often

assistant state's attorneys and defense

counsels are not adversaries. Rather,

modern criminal courts are

characterized by cooperative relations among

the judges and attorneys. They

cooperate because it is in their mutual self

interest to dispose of as many cases as

possible in a rapid and informal

manner. This cooperative relationship has

led many to contend that criminal

courts operate much like any other

bureaucracy.

Parkinson's Law — that venerable axiom of bureaucratic behavior — states that the resources required to perform a given task increase with the resources available to complete it. Within the context of this analysis, Parkinson's Law, if applicable, means that members of the "court organization " would not make good use of additional resources.Instead, they would be inclined to operate at about the same level. They would obtain about the same proportion of convictions and dismissals in about the same amount of time, and would use the additional resources to achieve personal goals.

Data analysis

A better idea of the value of increased

resources can be obtained by comparing

conviction rates, dismissal rates, and

average processing time for felony cases

in Cook County at two different points

in time. The first data come from the

classic Illinois Crime Survey conducted

in 1926 by the Illinois Association for

Criminal Justice. The second set of data

comes from a 1972 study by Jacob and

Eisenstein.

In 1926 there were only seven judges in the old Cook County criminal court, while in 1972 fifteen trial judges manned the Criminal Division of the circuit court. Interestingly enough, however, the number of defendants handled by the fifteen judges in 1972 was actually less than the number handled by the seven judges in 1926 (5,253 in 1926 4,281 in 1972). (The 1972 figures were computed from data included in "Statistical Report; Bonds, Cases, Fees, Fines, and Costs; December 1st to November 30th 1970-73" prepared by Matthew J. Danaher, Clerk of Circuit Court, p. 5, The 1926 figures came from Illinois Crime Survey, p. 43). If judicial caseloads are computed by dividing the number of defendants handled during a year by the number of judges handling criminal cases, it can be seen that between 1926 and 1972 the average felony caseload in Cook County trial courts decreased by 62 per cent. In 1926 the average caseload was 750 per judge per year, in 1972 it was 285. The number of assistant state's attorneys also increased significantly during this period. In 1926 there were between 28 and 35 assistants assigned to handle felony cases, while in 1972 there were 50, It was not possible to determine the exact number of prosecutors assigned to trial courts, however, so caseload figures for prosecutors couldnot be computed.

Disposition rates

When the dispositional rates of the

1972 trial courts are compared with

those of the 1926 trial courts, some

interesting differences emerge. First,

6/ August 1976/ Illinois

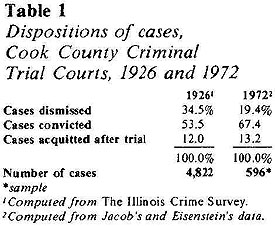

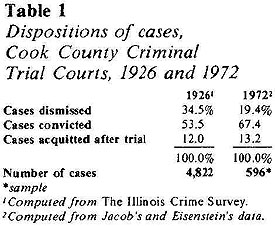

despite the lightened workload in 1972, the median number of days between grand jury indictment and the ultimate disposition of a case rose from 75 days in 1926 to 151 days in 1972, an increase of about 100 per cent. Table 1 breaks down the various dispositions of criminal cases in 1926 and 1972. At first glance, it appears that, despite the longer processing time, the conviction rate in 1972 is higher. The proportion of cases dismissed declined by about 15 per cent and the proportion of cases convicted increased by about 14 per cent.

Although these figures are correct, they should be viewed cautiously. Comparisons between 1926 and 1972 trial court statistics are not very meaningful, because since 1926 many changes in the nature of the dispositional process have taken place. Most of these changes relate to the role performed by the preliminary hearing courts.

Before a felony case can be sent to the grand jury, and eventually to a trial court, a judge in a preliminary hearing court must first enter a finding of probable cause. Besides conducting preliminary hearings, the preliminary hearing court judge also performs a screening function. He attempts to dismiss, at an early stage, weak or non- serious cases. He can also accept guilty pleas to felony and misdemeanor charges. Between 1926 and 1972 the manner in which the preliminary hearing court judges performed this screening function changed significantly. This has important implications for the types of cases that actually went to trial and makes comparisons between 1926 and 1972 trial court statistics tenuous. For instance, in 1926, 40 per cent of all felony cases eventually filtered through the lower courts and the grand jury to a trial court, while in 1972 only 11.5 per cent of all felony cases were sent to a trial court. In 1926 the lower courts which conducted preliminary hearings dismissed or entered findings of no probable cause in 50 per cent of all felony cases; in 1972 this figure rose to 75 per cent. This means, of course, that in 1926 the trial courts were probably handling many weaker cases (cases not screened out by the lower courts) than were the trial courts in 1972. This could well account for the greater dismissal rates in the 1926 trial courts.

Another significant difference

between trial court operations in 1926 and

1972 concerns guilty plea rates. In 1926

only 0.15 per cent of all felony cases

resulted in guilty pleas in lower courts.

In 1972, however, 16.9 per cent of the

felony cases resulted in guilty pleas to

felony or misdemeanor charges at the

preliminary hearing level. This indicates

that many defendants who would have

"copped" a plea at the trial level during

1972 did so at an earlier stage. Hence,

the guilty plea and conviction rates for

1972 and 1926 are also not strictly

comparable.

Rates of entire system

While differences make the comparison

of trial court disposition rates for

1926 and 1972 not wholly meaningful,

the real impact of the reduced workload

of trial court judges can be assessed in

another way. The disposition rates for

the entire system (preliminary hearing

court dispositions, grand jury dispositions,

and trial court dispositions) in

1926 and 1972 can be compared. If the

reduced workload of trial court judges

has enabled them to handle their

caseload more effectively, this should be

reflected in lower dismissal rates,

higher conviction rates, etc., for the

felony disposition process as a whole.

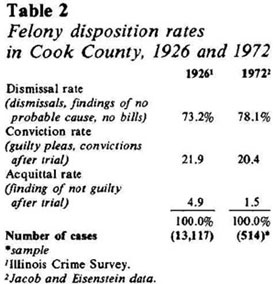

An examination of these overall rates

leads to some revealing results as shown

in Table 2. In 1926, 73.2 per cent of all

cases were dismissed by a lower court or

a trial court, resulted in a finding of no

probable cause by a lower court judge,

or an indictment was not returned by the

grand jury. The comparable figure for

1972, 78.1 per cent, shows that the

decreased workload did not result in a

lower overall dismissal rate. In 1926 the

overall conviction rate for the Cook

County criminal court system was 21.9

per cent, while in 1972 it was 20.4 per

cent. A 62 per cent reduction in the

workload of criminal court judges

between 1926 and 1972 resulted in no

increase in the conviction rate of felony

cases in Cook County. An average case

took about twice as long to process, and

there was almost no difference in the

overall dismissal and conviction rates.

Conclusion

These facts cast some doubt upon the

belief held by many that Cook County

criminal courts will operate better, i.e.,

produce higher conviction rates, if more

judges are appointed. Unfortunately,

however, the facts shed little light upon

the factors which do account for the

apparent malfunctioning of the system.

Much more study is required to truly

understand how and why the system

operates as it does. The most important

area to be considered is the

interrelationships among those who control

the felony disposition process — the

judge, the prosecutor and the defense

counsel. One must look to the structure

of the "court organization."

In Cook County the disposition of the vast majority of felony cases is controlled by a small group of judges, assistant state's attorneys, public defenders and regular criminal practitioners. These individuals have mutual interests because they desire to dispose of their caseloads as expeditiously as possible. In a vast majority of cases they have the power to do this, because together they control all of the vital aspects of the process (set bail, initiate charges, determine the nature and number of charges, make motions, determine guilt or innocence, sentence, appeal, etc.). In order to improve the quality of criminal justice in Cook County, those concerned with its reform must begin to grapple with the implications of having so much power vested in such a small and cohesive elite. ž

August 1976/ Illinois Issues/7