FIRST IN A SERIES OF FOUR ARTICLES By BRITTA B. HARRIS

A Lincoln housewife, and mother of five,

Ms. Harris followed and researched the

events of the Oakley Dam controversy for

seven years in order to write her master's thesis in public administration for the University of Illinois at Urbana. She has also taught political science at Lincoln College.

The drama of Oakley Dam: To build or not to build,

that was the question

A struggle spanning three decades pitted the Army

Corps of Engineers and the City of Decatur against

conservationists and farmers with the U of I in the

middle. When the curtain fell, there was no dam, but

the way we make decisions had been exposed

ONE OF THE BITTEREST and most

protracted controversies in the recent

history of Illinois is finally over.

Although the debate over Oakley Dam

has stretched on for more than 30 years,

the majority of the state's citizens

outside of east central Illinois have

never heard of it, and the few who have

did not understand the baroque complexity of the largest public works project ever proposed for central Illinois. Four U.S. senators, Republicans Charles Percy and Everett Dirksen and Democrats Paul Douglas and Adlai Stevenson, two governors, Democrat Otto Kerner and Republican Richard Ogilvie, and two congressmen, William Springer and Edward Madigan, both

Republicans, gave it strong support. But

in spite of this powerful official approval, combined with the determined promotion of the U.S. Corps of Engineers, this Sangamon River project was ultimately, and perhaps inevitably, doomed.

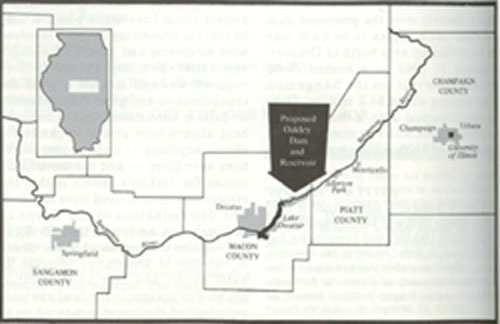

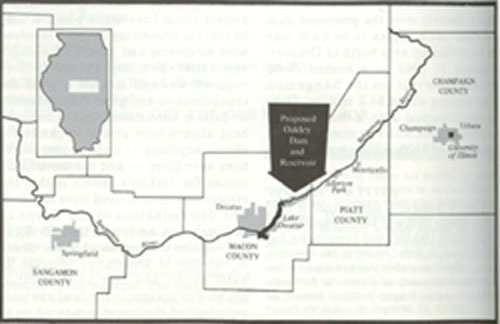

Since 1945, dozens of government

agencies, the University of Illinois,

many private organizations and lobby

groups and countless private individuals

argued fiercely over the proposed dam

and reservoir complex to be built near

the rural Oakley area north of Decatur.

Proposed in 1945 as a modest flood

control reservoir on the Sangamon

River costing about $4.8 million. Oakley mushroomed into a huge, multi-purpose project with two reservoirs and

a price tag of $120 million before it was finally cancelled after an investigation

by the federal General Accounting

Office in 1975. This report and the

persistent efforts of a cadre of citizens

concerned that the proposed reservoir

would flood Allerton Park near Monticello caused the Corps to withdraw from

the project it had championed so

vigorously for over three decades.

No one simple reason can be given for

the Oakley debacle, but a cluster of

failures in communication, research and

coordination can be discerned by

following the threads of controversy

and litigation over the years. If poor

coordination caused the failure, the next

question is whether our society, our

institutions, are organized in such a way

that any proper planning for such a

project could have taken place. It may

be that the competing interests involved

were so diverse and inherently antagonistic that the comprehensive effort

required was and is quite beyond the

capabilities of any governmental entity

or private consortium. But Americans

have always been able to organize for

almost anything — if the proper incentives were there — and the more likely

reason for Oakley's failure is that the

project was ill conceived from the start.

The determination of the Corps to

undertake an ambitious public works

project like Oakley matched the desire

of the city of Decatur to increase its

water supply and save Lake Decatur,

but neither reason, in the final analysis,

outweighed the environmental, economic and agricultural drawbacks so

loudly proclaimed by Oakley's detractors.

Because water is a migratory resource, flowing across political boundaries, a special set of requirements is necessary for purposes such as water

supply, water quality, flood control,

farm and municipal drainage and

recreation, as well as for growing

demands to preserve natural resources.

Illinois is water-rich, but many areas in

the state are short of water because of

geologic conditions and changing demographic patterns. The state has more

water miles than most states, a high rate

of replenishment through rainfall and

has twice the national percentage of

flooding. Consequently, flood control

has become a major government activity, as has the use of surface water for

water supply and recreation. Large

water projects benefit some communities while others suffer adverse impacts.

Cooperation between communities

competing for water use and control is

rare. Furthermore, water resource

planning has been complicated by

confrontations between developers and

conservationists. Another difficulty is

that the time-honored use of water

management tools such as channelization and multi-purpose reservoirs is

more often challenged by citizens

equipped with the engineering, hydrological and ecological expertise to

support their objections. Finally, the

ultimate problem in water resource

September 1976 / Illinois Issues / 3

First proposed for flood

control, the dam was

changed by the Corps

with Decatur support to

include water supply,

recreation and

pollution control

development is to find a common

ground where all these interests can

agree and public responsibilities can still

be met.

For more than 30 years, the U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers worked on the

development of a dam and reservoir

system on the Sangamon River as part

of a comprehensive flood control plan

for the entire Illinois River watershed.

The Oakley Project evolved from a dry

basin for flood control to a pair of multipurpose reservoirs providing flood

control, water supply for the city of

Decatur, recreation and, at one time,

water quality for pollution control. In

1966, when the proposed project was

expanded for recreation and pollution

control, there were angry protests from

many area citizens. Sufficient water

storage for the four "benefits" required a

high dam, which would have backed

reservoir waters upstream to a point

where thousands of acres of rich farmland, as well as forests in Allerton Park,

would have been flooded. Allerton

Park, located in Piatt County near

Monticello, is a 1,500-acre estate given

to the University of Illinois by the late

Robert Allerton, wealthy landowner

and son of a midwest tycoon. The

sacrifice of any part of the park, which is

used for educational, scientific and

cultural purposes, was considered

unthinkable by many people. A coalition of citizens led by university faculty

members and Champaign conservationists was organized to save the park.

Their dedicated campaign initiated an

incredibly complex chain of events

which eventually put the brakes on

project planning. After more than 30

years of human effort and public

expenditure, all that remains of the

Oakley mirage is some lingering bitterness and a classic public administration

case study in the pitfalls of narrow,

project-oriented planning.

During the course of the Oakley

mirage, several attempts were made to

establish comprehensive land and water

resource planning with coordination

and communication between local, state

and federal agencies. Most of these

efforts failed because of secrecy, misunderstanding, a lack of shared goals,

motivation and sufficient authority.

Timing also played a part in Oakley's

failure. The struggle between the Oakley

and Allerton forces peaked at a time

when debate over environmental issues

was developing. Citizens were more

aware of the value of irreplaceable

natural resources such as Allerton Park.

Environmentalists insisted on wide

consultation to balance information

presented by public agencies to promote

projects such as Oakley.

The Corps' methods

Many issues came and went while

Oakley remained on the drawing board,

but sustained throughout were questions related to the methods used by the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to advance its project. Specifically, detractors disagreed with the Corps' methods

of estimating future benefits, especially

those for flood control. The Corps is one

of the oldest and most powerful bureaucracies in the nation and is skilled in the

art of political manipulation. It has had

many powerful critics. In 1955 the

Hoover Commission on Organization

of the Executive Branch of Government

said the Corps' benefits were frequently

overstated. The Hoover Commission

said national policy led to the authorization of many projects of questionable merit, and it offered suggestions for the

transfer of the Corps' civil functions to

another agency. Water resources development, the report said, should be on a

regional watershed basis rather than on

a project basis which might favor local

interests.

|

The recommendations made by the

Hoover Commission failed, and the

Corps continued to exercise its vast

power over the development of water

management programs in the country.

In 1975, the Corps' powers were again

being reviewed, but this time from the

point of view of increasing that power.

Under study in 1975 was a plan to

expand the Corps' jurisdiction of

waterway authority to cover every body

of water in the nation. All lakes and

streams, even irrigation ditches and

marshes, could, under current proposals, come under the authority and

supervision of the Corps. An examination of the Corps' espousal of the Oakley

project can provide some insight into

how it has worked in the past and

perhaps some notion of whether its

power should be enlarged in the future.

|

|

The COAP

As the Oakley drama unfolded.

individuals and groups adhering to

policies expressed by the Corps and the

city of Decatur were opposed by those

sharing views shaped by the Committee

On Allerton Park (COAP), the coalition

which was dedicated to save the park

from permanent flood damage. Between

these polarized positions there were

important interests whose positions

shifted during the course of the struggle.

4 / September 1976 / Illinois Issues

Piatt County, designated by the

Corps' Oakley design plan as the area to

accommodate the backup of Oakley

floodwaters, became a major arena of

political strife. Many Piatt citizens

objected strenuously to plans for flooding; others played with the idea of bringing in even more water to encourage the

development of a recreation-based

tourist economy. Others in the county

appealed to state and local officials for

comprehensive valley planning.

Throughout the years of conflict, the

University of Illinois had trouble

establishing a policy towards the project. Torn between its legal responsibilities for the Allerton property and its

desire to maintain popular good will for

the university, the University Board of

Trustees first bowed to the project's

inevitability and then retreated, claiming the need for further study and

review. The board agreed to a compromise proposed by the state, but when the

Corps forced compromise changes,

there was displeasure and distrust. After

more studies, the board withdrew

university support for the project.

State government

The policies of the state government,

shaped by three successive administrations, were basically political, and the

ambitions of individuals sometimes

conflicted with objective professional

standards. Because of this and the

differences between several sets of

standards involved in the state's administration of natural resources, the state's

Oakley policies were often inept and

confused. State officials successively

promoted the project, offered compromises, and sought neutrality. The

project was never considered solely

from the broad vantage point of regional planning where a wide range of

interests in the Sangamon River Valley

could be reviewed.

Decatur, anxious to augment its

municipal water supplies with water

from Oakley, became the Corps' earliest

and most dedicated ally. City leaders

used their political influence to persuade

slate and federal support of Oakley. The

project, which had been on the Corps'

drawing boards since 1937, languished

for many years until the influence of

Decatur overwhelmed former objections to the project. Decatur city

officials had worried about the city's

future water supply for many years, and

it was natural that they would look to the federal project as a likely solution to

their problem. Located just a few miles

north of Decatur, the project had the

potential to serve many purposes for a

growing population.

|

Like many cities in Illinois, Decatur

had a municipal water supply reservoir,

but unlike others, it was constructed on

the main stem of the river. In 1921, the

reservoir. Lake Decatur, was placed on

the Sangamon River to accommodate

growing water needs of the A. E. Staley

Company, one of the city's chief industries and destined to become one of the

nation's largest grain processors. Considering the tons of sediment, which

poured through the river's channels

from thousands of acres of highly

cultivated upstream areas, a mainstream reservoir was a risky venture.

Lake Springfield, further downstream,

and also a combined water supply and

recreational reservoir, had been placed

on a tributary of the Sangamon River

where siltation rates were considerably

lower. The extent of Decatur's gamble

was soon obvious. Between 1922 and

1936, the lake lost 14 per cent of its

storage capacity. Thousands of tons of

silt, carried by swift Sangamon flood-

waters during the rainy season, settled in

Lake Decatur. In 1946 the sediment was

two feet deep near the dam and three

feet deep in the upper part of the

reservoir, up to the spillway level in

some places.

Large volumes of silt resulted from

the intensified cultivation in the upstream drainage areas. In Piatt County,

land planted with intertilled row crops

such as corn and soy beans was increasing at a high rate. In 1953 and 1954

worries about a shrinking water supply

were intensified by a drought which

caused Lake Decatur to drop alarmingly. Future droughts were predicted

by the Corps and concern developed

over the city's ability to provide water

for peak industrial demands. City

leaders organized a search for more

water and were advised by engineers

that the most feasible plan was the

construction of an upstream reservoir to

serve as a silt trap.

Decatur lobbyists

Decatur concentrated its efforts on

obtaining congressional approval of the

Corps' Oakley plan. Until Decatur

began lobbying, the plans of the Corps

for development on the Sangamon

River had been turned down by Congress because of strong opposition from

area conservationists and farmers.

Conservationists fought any engineering projects on the Sangamon, especially channelization — the dredging of

the river channel for faster water flow.

They opposed any change, which would

alter or destroy fish and wildlife habitats. Many downstream farmers, long

adjusted to the risks of farming rich

bottomland soil along the river, were

sensitive to any water management

, which might interfere with their use of

the land.

Farmers in upstream regions also

objected to the dam since there was the

risk of reservoir water backing up and

being held at high levels. Upstream

farmers were joined by residents in

Monticello, the Piatt County seat. In

Monticello there were objections to the

Corps' plans because of fears that a dam

on the Oakley site would cause flooding

|

|

Cast of Characters Act I

U.S. Corps of Engineers: one of the nation's

oldest and most powerful bureaucracies, the

Corps first put the Oakley Dam on its drawing

board in 1937 and pushed vigorously for its

construction until the project was scrapped

in 1975

City of Decatur: worried about the future of

its water supply because of the siltation of

Lake Decatur and the needs of a burgeoning

population and its vital grain processing

industry, the city was the Corps' strongest

ally throughout the Oakley drama

Committee On Allerton Park (COAP): dedicated

to the preservation of the University of Illinois'

priceless 1,500-acre park, the coalition entered

the drama's action at a crucial point and proved

to be Oakley's most vociferous and

effective opponent

Citizens of Piatt County: upstream from the

proposed site of the dam, area residents feared

that the backup of Oakley waters would flood

farmland and damage the municipal sewage

system of Monticello, Piatt County seat

State of Illinois: divided over the merits of

Oakley, officials and agencies of the state were

left out of early planning efforts and played

only cameo roles until forced to take sides

late in the action

University of Illinois: torn between the desire

to save its own Allerton Park and the fear of

alienating the university's powerful supporters,

the U of I Board of Trustees vacillated until

the drama's final act

U.S. Congress: responding to the strong support

of the powerful Illinois delegation, the Congress

approved each increase in the cost of Oakley

until a General Accounting Office report showed

the dam's costs would far outweigh its benefits

|

|

September 1976 / Illinois Issues / 5

Conservationists fought

the dam to save Allerton

Park and found an ally in

farmers who felt their

land was more threatened

by the dam than by floods

near the city and damage the municipal

sewage system. There was little confidence that the Corps could manage the

reservoir to prevent floodwater backups. Congressman William Springer

(R., Champaign), after considering the

strong opposition, told Decatur's leaders that it would take a miracle to get

Oakley started.

The push for Oakley had more going

for it in 1954. Economic conditions were

changing in Illinois, and agricultural

interests were overshadowed by the

compelling demands for industrial

expansion. Decatur was regarded by

some as the industrial gateway to central

Illinois, and its needs in a growing state

economy assumed greater importance.

Primarily interested in its own problems, Decatur lobbied for federal

approval of a water supply function in

Oakley's design. This time, there was

strong congressional support for Oakley. The late U.S. Sen. Everett Dirksen

(R., Pekin) never doubted the Corps

claims for Oakley or Decatur's need,

and U.S. Sen. Paul Douglas (D.,

Chicago) agreed that with some changes

there could be a reservoir. Planners in

the Chicago district office of the Corps,

which had jurisdiction over the Sangamon River development, were very

receptive to Decatur's overtures, especially since the Chicago office had yet to

build a major reservoir project.

Decatur's lobbying efforts were successful, and Congressman Springer's

doubtful miracle occurred. A revised

Oakley project was launched in 1956

with a new price tag of $22.8 million and

a Decatur agreement to pay a share

($5.4 million) of the cost. Rosy predictions for sudden wealth in central

Illinois did not convince everyone, and

objections continued to impede progress. The Korean War slowed down

federal public works spending, but

persistent political pressure overcame

all obstacles. In 1962, a new Oakley

design was approved, this time at a cost

of $27.2 million. Recreation was added

as a benefit at the insistence of Sen.

Douglas. Jubilant about the prospect of

Oakley's success, a Decatur city councilman said, "We've got a lake for about

half the price we would have to pay for

one of our own. The determination of

the Decatur Association of Commerce

and the City Council carried on through

war, indifference and opposition."

Throughout the entire Oakley controversy, Decatur's approach was characterized by this same tough single-mindedness. Even when the odds turned

decisively against the project, city

leaders refused to admit the possibility

of defeat and fought to the very end.

More resentment

Following congressional approval,

the 1962 version of Oakley was a reality

for opposition forces to contend with.

Voices of protest were again heard, but

this time more technical arguments were

offered. There was also resentment

against a project designed solely for

Decatur and Macon County, and there

was criticism that the more costly

project had not been put to the test of

public hearings. Farmers and conservationists again advanced alternative

proposals to provide cheaper and more

efficient methods of flood control.

Some critics thought the new dam

should be located below Decatur,

downstream where it would be more

protected from siltation. There, they

said, it would truly serve a flood control

purpose by containing flood waters

from the city. Most opponents were

suspicious of the Corps' motives. They

believed that the Chicago District,

anxious to build its first major reservoir,

selected the Oakley site because the

combined benefits of water supply,

flood control and recreation made the Oakley package more attractive. Critical of the Corps' decision, opponents

claimed the Corps' attitude was not,

"Where is the best place to put a dam?"

but instead, "How can we put a dam

here?"

More specific objections related to

topography. The land, it was said, was

too flat for water storage. With high

rates of runoff, it was necessary to take

the reservoir too far back into the watershed, using an excessive amount of

highly developed agricultural land.

Critics also said that Oakley's flood

control function would be useless

because Decatur's industrial needs

required a full reservoir at all times.

High water levels were also needed

during summer months when there were

peak demands for recreation. A full

reservoir contradicted the flood control

concept which required summer and fall

drawdowns to lower water levels for the

accommodation of late winter and

spring floods. Furthermore, farmers

claimed high reservoir levels would

permanently damage farm drainage

systems and keep the land soggy during

critical periods of the growing season.

Many downstream farmers were willing

to take occasional losses from flooding

because the losses were more than made

up by high yields from rich bottomland

soils. A dam at Oakley would curtail

flooding, but farmers feared that the

lower Sangamon River would be much

too high during the planting season.

Reservoir management was known to

be difficult, and water releases often

took longer than predicted. Downstream farmers feared the long period of

soaking more than they feared floodwaters, which drained, away in a few

weeks time each spring. Oakley opponents pointed out that agencies such as

the Corps, which construct, operate and

maintain multi-purpose resource projects are required to build only projects

which yield public benefits. It was

argued that since flood benefits alone

could not justify Oakley, the Corps

needed to count the benefits of water

supply and recreation to bolster a

sagging cost-benefit ratio.

Further enlargement

During 1964 and 1965, there were

widespread rumors that the Corps,

having difficulty with its cost-benefit

ratio, was planning to add a new

purpose and enlarge the reservoir.

Officials from the University of Illinois,

6 / September 1976 / Illinois Issues

with little information about the possible effects of flooding in Allerton Park

under the 1962 Oakley design, were

alarmed that a larger dam would bring

even more water. Objections were made

to Congressman Springer that Oakley

planning was proceeding too rapidly.

The congressman gave assurances that

the university would receive step-by-step notices of project development, but

in spite of his assurances, Oakley

planning continued to be secret.

Speculation about Oakley ended in

1966 when Congressman Springer

announced that Oakley had been doubled in size at an estimated cost of $62.4

million. Corps officials described the

changes as mere refinements. But by

raising the dam 15 feet from 621 above

mean sea level to 636 feet, adding a new

feature as well as channelization, they

had, in effect, given the project a major

overhaul. The new feature, low flow

augumentation, was the addition of

more water to dilute polluted water

downstream from Decatur, Since the

impoundment of the Sangamon River

by Lake Decatur in 1921, the river's flow

immediately downstream from Decatur

sometimes consisted of little more than

effluent from Decatur's sanitary plant.

This new purpose of dilution immediately became a target of Oakley opponents who regarded it as a crutch to

support the project's weak economic structure.

The Corps' decision to redesign Oakley without the benefit of public

hearings further aggravated opposition,

and the stage was set for one of the

longest political battles in Illinois history.

Subsequently, the struggle was carried into courtrooms, legislative chambers and council rooms at the federal,

state and local levels. The Corps of

Engineers, with everything to gain,

resisted demands for changes. The

Committee for Allerton Park (COAP),

with nothing to lose, refused to give up

its efforts to save the park. It is possible

that if the compromise had stuck

together, the Oakley Dam project would

have been accepted. What is certain is

that a small group of citizens, which

used every lever of publicity and political power, finally succeeded in bringing

the weight of public opinion and official

sanction against the project and its

powerful bureaucratic sponsor.

Next month — Oakley: the early years.

September 1976 / Illinois Issues / 7