By POLLY ANDERSON Higher education reporter for The Champaign-Urbana News Gazette since 1972, she is a graduate of the University of Illinois College of Communications

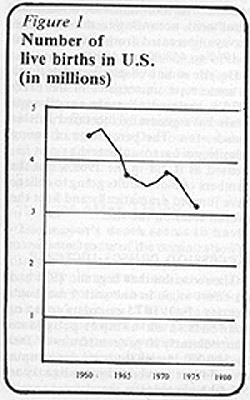

The end of the baby boom in the early 1960's means a drop in the college-age population in the 1980'sCollege enrollment declineTHE END of the long postwar baby boom is not news to most people, but it's about to make news in Illinois colleges and universities. The depleted ranks of newborns, starting in the early 1960's, will soon be the depleted ranks of 18-to21-year-olds, the traditional age of college undergraduates. And that could mean many empty seats in Illinois college classrooms. The severity of the baby boom decline can be seen in figures by the U.S. Bureau of the Census in its "Statistical Abstract of the United States 1976." In 1945, there were 2.86 million live births in the U.S. The number of live births soared to 3.63 million in 1950, to 4.10 million in1955 and 4.26 million in 1960. There was just one more year with an increase, to 4.27 million in 1961, before the decline began. In 1962, there were 4.17 million live births; in 1963, 4.10 million; in 1964, 4.03 million, and in 1965, 3.76 million.The lowest number of births during the1960's was recorded in 1968, when 3.50 million babies were born. The total climbed a bit during the next three years before plunging below 3.20 million by the mid-1970's. Gustav J. Froehlich, head of the University of Illinois Bureau of Institutional Research, is the accepted expert on the enrollment patterns of Illinois higher education. His yearly enrollment study is known simply as the Froehlich Report and is used by agencies throughout the state, including the Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE). "I think it's fairly certain that it won't be long, no later than 1980, when we're going to hit a peak in high school graduates," he said in an October interview, "and also in the age range from which we usually pick up our college students, 18 to 24. Practically every demographic study that I've seen, and some that we've made, agree on that. Maybe they're off one says one year, one says another but we know that the peak's coming and it's going to be with us fairly shortly," he said.

Of course, elementary school administrators have been grappling with the demographic facts of life resulting from the baby boom's end for several years now, and high school administrators are just beginning to face similar problems. What makes the situation more complex for higher education planners, though, is that demographics is not the only factor in predicting enrollments.

Predict the number of 5-year-olds in a given area, and you've pretty well predicted the kindergarten enrollment. But not every 18-year-old decides to enroll as a college freshman, and not every college freshman is an 18-year-old.

In the short run, the state of the economy is probably the biggest factor in determining enrollment changes. Froehlich theorizes that economic downturns have a two-stage impact. "In the early years of a depression, enrollments will go up," he said. "People still have some money; they don't have a job so the attitude is, 'All right, I'll go get a master's degree, and maybe I'll get a better job.' If the depression lasts, that cushion of money is gone and the new job doesn't materialize, then the bottom drops out."

In the longer run, social trends such as the public's opinion of the value of a college education and the aspirations of women and minorities, affect enrollment levels as much as population trends. So too does the availability of financial aid. Another factor important in recent years has been the increasing numbers of older adults taking college courses.

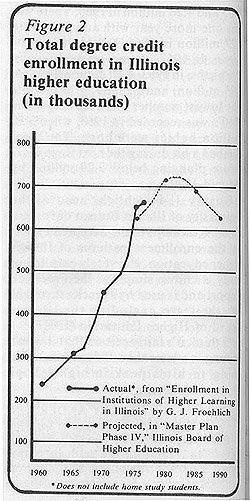

In the 1960's, these various factors all worked together: expanding numbers of young people coupled with rising aspirations of women, minorities and the lower and middle classes, all caused enrollments to increase just about as fast as new classrooms and campuses could be built. The total statewide on-campus enrollment, according to the Froehlich surveys, increased from about 200,000 in 1960 to 458,000 in 1970.

Despite some well-publicized declines at some state universities in the early1970's, the overall state enrollment totals have generally increased in this decade, too. The percentage of young people going to college has not increased as it did in the 1960's, but the numbers of older adults going to college have jumped dramatically and kept the overall total on the rise.

Recession causes increase

15/ February 1978/ Illinois Issues

ment, counting off-campus students, increased 1.4 per cent to 667, 000.

Figures gathered by Froehlich and the IBHE for fall 1977 showed on-campus enrollment up about 1.7 percent, to

554,000 and overall enrollment up about 3 per cent, to 687,000.

So enrollment declines aren't here yet.

But most planners expect that demographics will lead to enrollment declines soon, even with other social trends taken into account.

A 1977 study by the American Council on Education, Washington, D.C., considering demographics, migration patterns and numbers of students going to college out of state, projected a 16.2 per cent decline in "traditional age" (18 year-old) freshmen attending school in Illinois between 1975 and 1985. TheIBHE'S latest detailed projection, made in the 1976 Master Plan Phase IV, predicts as "most likely" an overall enrollment peak of about 717,000 in1981, then a drop of 11 per cent over the next nine years, to about 638,000 in 1990 about the same level as was projected for 1976.

If the coming enrollment decline has been about 15 years in the making, does this mean that planning for it has been going on just as long? Not too surprisingly, the answer is "No."

The IBHE'S Master Plan Phase II, for example, in 1966 predicted the future as follows: "The expanded population of young persons from 1965 to 1980 will produce more offspring than ever before, and these, in turn, will grow into the ever-expanding college-age population from 1983 until the turn of the century. College enrollments are increasing much more rapidly than the college-age population. In other words, college enrollments will continue to rise even in the unlikely event that the number of college-age youth were to become static."

Plan predicts peak

But Master Plan Phase III, and Phase IV, approved two years ago, did not deal with the issue of declining enrollments per se. Instead, they talked about how to deal with the enrollment bulge how to serve the extra students added on in the last half of the 1970's, whose numbers would disappear by around 1990. Thus, the first recommendation in Master Plan Phase IV states, "The allocation of resources to accommodate peak enrollments through the early 1980's should be made in a manner that is cognizant of probable subsequent enrollment declines to levels comparable to current enrollments."

In other words, the plan was saying to colleges and universities, "If you can double up a bit for a while, and do without many new buildings and programs and such in the next few years, you won't have to cut much when enrollments begin dropping five to ten years from now."

The IBHE this fall began studying the enrollment issue again, and this time appears to be facing up to the fact that the problem may be more difficult to solve than the master plans have indicated. The latest study was sparked by a letter from Gov. James R. Thompson sent to the board in July which asked such things as whether faculty retraining programs are planned and how top revent underutilization of higher education buildings. "What can we do in Illinois to redirect emphasis from the growth syndrome of the 1960's to a

focus on improving the quality of our programs?" Thompson asked.

John Folger, policy coordinator of the Education Commission of theStates, a national organization, was one of four experts invited to address the IBHE in October on enrollment and other coming problems. "Institutions don't have experience with retrenchment," he said. "As a political activity, it is something we don't know how to deal with."

Colleges and universities cannot cut costs rapidly as their enrollments decline, experts say, for many reasons. For one thing, tenured professors are difficult if not impossible to lay off, they cannot be retrained to switch from English to medicine as an assembly-line worker is retrained to switch from a Pinto to a Lincoln Continental. In addition, schools can't do much to cut fixed costs. As Jack W. Peltason, head of the American Council on Education, put it in a recent speech in Champaign, "You still need a laboratory whether there are 40 or 45 kids in there; you have to heat a classroom whether there are 50 kids sitting there or 60."

In addition to whatever limited cost-

6/ February 1978/ Illinois Issues

1. Finding enough students from

nontraditional college-bound groups those over age 24, minorities and others not now in college to overcome the decline in traditional students.

2. Asking the state not to decrease funding as enrollment declines with the extra state dollars-per-student to be invested in

improving the quality of education by decreasing

class size, for example.

3. Accepting the decline as the fate of free market forces

resulting in the death of weak programs which did not deserve to live anyway.

The first solution is the one most often cited by higher education officials. For example, college administrators often criticized the Master Plan Phase IV's projections by arguing that they did not take enough into account the increasing numbers of older adult students. But Froehlich and others caution against overestimating the effect of the older adult student, particularly in the state universities. "The big increase in older people going to school is in the junior college," he said. "You don't see it so much in universities. And we find it [the increases] in the junior colleges, not in the baccalaureate programs the kind of programs which mean transfer to a senior institution but in the occupational areas and in the general studies [recreational-type courses]. These people are not really

interested in getting any further degree. "Even the older adults who do go to universities will not affect all campuses equally." Many colleges and universities are not ideally positioned, geographically or philosophically, to serve a new student clientele," according to a November IBHE staff study. "Many of the state's largest universities are in areas of relatively low population and are not likely to attract many of the 'new' students."

Already, according to the IBHE'S annual Data Book on Illinois Higher Education, the numbers of older adults vary widely from campus to campus,with the greatest numbers at urban campuses. For example, in fall 1975, according to the book, the average undergraduate at Chicago State University was 25.6 years old; at Western Illinois University at Macomb, the average was 19.8 years.

(Though schools in rural areas stand to do the worst with older students, at least one such Illinois campus probably will not face much of a decline in enrollment demand the University of Illinois Urbana campus. Froehlich and other experts feel that a state's "flagship" state university the most prestigious research and teaching institution, which now turns away applicants will have little trouble in meeting enrollment goals in the future.)

Another difficulty in serving older students is that it will probably cost more, on the average, to serve them. It costs money to extend class hours into the evenings and on weekends and to create special counseling programs and new instructional methods geared to older adult needs. Furthermore, students who study only part-time often cost as much in administrative expenses as full-time students.

Colleges seek solutions

The second route using the decline

in enrollments to improve quality is naturally attractive to college and university administrators. In its November report, the IBHE staff reasoned that "productivity" (the ratio of costs to overall benefits) could be maintained in an era of declining enrollment in only two ways: cutting costs or increasing quality.

"While the most apparent way to maintain productivity in the face of declining enrollments may be to cut costs, e.g., lay off staff or close buildings, it is unlikely that cost-cutting alone could keep up with productivity declines," the report said. Among the ways to improve quality, the report suggested, are consolidating weak programs and strengthening those in fields needed the most by society, improving faculty teaching skills, and making more flexible programs to meet student needs.

A third "solution" of sorts would be a passive approach accepting the notion that students are consumers. An exponent of such a free market philosophy might well argue that the choices students make as to which college to attend will rightfully determine which colleges deserve to survive. Such a system is already in effect, to some extent, in the private college sector,where college closings due to declining enrollments are not unheard of even in these pre-decline years.

Since public higher education is subsidized primarily by the taxpayers rather than by student tuition, no public campus is likely to be shut down because of declining enrollments. However, it is likely that individual programs at these campuses might be cut. The IBHE this fall approved a system of program review at state universities, and enrollment trends is one of the criteria to be used in determining which programs, if any, should be discontinued.

Budgetmakers in Springfield for the next decade will have to resist the temptation to look just at enrollment figures as the criteria for a university or college total budget, or wholesale budget cuts will result. The best solution to the coming enrollment problem will likely be a combination of the above alternatives: some careful program cuts and cost reductions at campuses facing significant declines, improved programs to bring in more older adults and other previously excluded potential students, and improvements in quality education for all students.

17/ February 1978/ Illinois Issues

|

|||||||||||||||