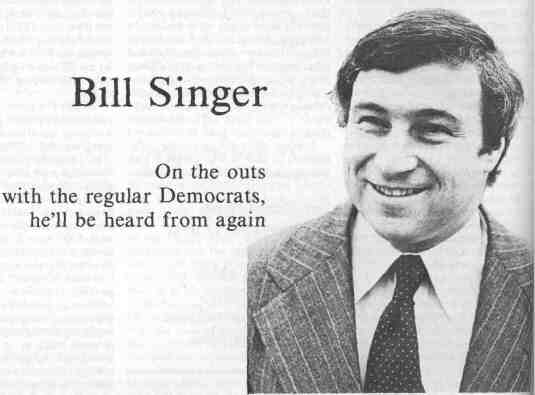

By MILTON RAKOVE *I once saw Bill Singer reading over a speech at 6 a.m. in the back seat of a Chevrolet sedan the color of Lake Michigan at the end of November. Nineteen hours later he was the same gray-green color as he cat-napped between sentences, plotting the next day's campaign. The North Side reform Democrat hoped to take over and redirect the regular party Machine and to score a personal victory over Richard J. Daley. When it was all over, Daley was still in the pink, and the Cook County Democratic Central Committee was still coming up roses. Unlike other reform candidates who have faltered in the political arena before the political prince these last two decades, Singer understood that precinct organization was the source of Daley's strength. He respected the precinct workers who carried the load. The only problem was, as a classic independent 43rd Ward Jew, Singer drew his support by being a gadfly, an articulate and even brilliant reformer of Chicago politics. Therefore, he couldn't conduct a winning campaign without alienating his natural following. What was sad about Singer's campaign was the electorate's inability to recognize that Singer's instincts and Daley's instincts watered at the same hole. To put it another way, the only difference cast by their shadows was time and circumstance. I used to think of Daley and Singer as father and bastard son, sworn to fight to the death because neither could stand the unmistakable identity of their political roots. * Reprinted courtesy of the Chicago Tribune. Like Richard J. Daley, William S. Singer has always been a political man, a gladiator born to the arena. But, unlike the Catholic, conservative, working class-rooted Daley, Singer's political life has always been complicated by his Jewish, liberal, middle class background. Daley went to Nativity of Our Lord grammar school, De LaSalle Institute and DePaul Law School. Singer went to Horace Mann grammar school, South Shore High School, Brandeis University and Columbia University Law School. Daley interned in the 11th Ward headquarters under Joe McDonough. Singer interned in Sen. Paul H. Douglas' Washington office and clerked for federal district Judge Hubert Will. But both men foreswore a career in the logic and rationality of the law for one in the excitement, irrationality and uncertainty of politics. Career of improvisation Unlike Daley, however, who planned his political career methodically and carefully, Singer's political career has been more a product of happenstance and improvization. He worked in Bobby Kennedy's campaigns for senator in New York in 1964 and for president in Chicago in 1968. But Singer's candidacy for alderman in Chicago's 43rd Ward in 1969 was completely unplanned. "An independent group in the neighborhood was looking for a candidate to run as an independent," he told me in an interview. "1 was invited to a meeting.... They went around the table asking if 18/ February 1978/ Illinois Issues anyone was interested in running. I said I might be interested and that was it." Singer won over the Democratic machine candidate by 427 votes in a closely contested election, but won his second aldermanic term with 70 per cent of the vote in the ward, thus clearly establishing himself as a solid local vote getter. In the Chicago City Council, Singer was a key member of the small but active minority bloc and opposed the machine on matters he considered to be crucial to the city's interest. But he voted with the majority 95 per cent of the time on routine matters like appropriations for street cleaning, snow removal and sidewalks. "I loved being an alderman," he said. "I loved both parts of the job. You do two different things if you are a full-time, conscientious alderman. One of them is being a legislator. I loved that, even though there was great frustration. There weren't more than four or five major pieces of legislation that I finally got through. But there were a number of pieces of legislation that were defeated when I sponsored them, but were later picked up by the machine." "The other part of the job," Singer said, "was to serve your neighborhood and your constituents' personal needs. I loved that, too. I would come home nights really charged up because I had been able to moderate a crisis in theneighborhood. You dealt with everything from getting garbage picked up togetting a park for the neighborhood, or a zoning matter or a school situation."So Singer was, as an alderman, not just an opponent of the machine, but a close adherent to the machine's and Daley's basic philosophy that serving the personalneeds of constituents was the warp and woof of good politics and representation. Student of policy Singer also worked hard at mastering the details of major public policy issues such as budget, schools and neighborhood development. Here, too, he was a student as well as an opponent of the machine. "I spent a lot of time learning from Tom Keane," he told me, in the interview, "and have an enormous respect for him. I've never met anyone like Tom Keane. He was and is absolutely brilliant. He knew where everything was and that the dollars and cents were what made the city go." In 1972, Singer allied himself with Rev. Jesse Jackson to challenge Daley and his delegates to the national Democratic convention, and they succeeded inhaving the Daley delegation unseated, the worst blow that Daley suffered in his long political career. "He never forgave me for that, " Singer said. Then, in 1975, he gave up his seat in the council and tackled Daley in the mayoral primary. Daley won easily, although Singer got a moderately respectable 32 per cent of the vote to Daley's 56 per cent. "I came close to beating the machine," he said, "but not beating Daley. Daley won that election himself. He transcended the machine by 100,000 votes."

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |