By TIMOTHY S. BRAMLET A former Illinois Issues intern, he is now a journalism student at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana.

They've happened before; will they happen again?

Quake expectations in Illinois

WHEN people think or worry about earthquakes, they conjure up visions of a skyscraper in Los Angeles toppling into the Pacific Ocean, or of a Peruvian village being swallowed up in a black crack in the earth. Very few people think of Illinois and its midwestern neighbors as the sites of such disasters. But, records of earthquakes that have either occurred or been felt in the past indicate that Illinois may be just as susceptible to these catastrophes as any other place on the globe. The problem is, however, that Illinois is an extremely difficult area in which to establish a stabilized earthquake prediction capability. The far southern part of the state ranks among the most dangerous areas in the country, while the northern sector, including Chicago and Cook County, has sustained only minor damage in the past. But geologists are aware of the probability of major earthquake damage occurring in any part of the state and are constantly working to develop methods to help predict such a tremor before it occurs. Monitoring systems There is presently no foolproof method to detect and monitor earthquakes. But scientists are optimistic that within10 years they may develop a reliable earthquake prediction capability. Presently, two methods are used throughout the country to estimate where and when the next tremor will be. Geophysical methods involve the observation and interpretation of certain changes in the physical environment in earthquake-prone areas. Scientists, who now rely heavily on this system, have established seismograph stations all across the country, especially in high-risk areas. But some doubt exists as to whether or not earthquakes are always preceded by some change in the environment. It may be that some quakes occur without such changes, or shifting, in the earth's crust. Whatever the case, it is still difficult to determine how far the damage of a quake will extend. The other commonly employed method of prediction is based upon the statistics of prior shocks that have occurred in an area. These statistics are used to make guesstimates about when and where earthquakes may occur in the future. Earthquakes are often clustered together, and by mapping the centers of quakes that have occurred, "risk ratings" can be derived for the probability of future occurrences in an area. These ratings help to develop criteria for design of earthquake-resistant buildings and homes. One problem of the statistical methods is that their generalized prediction is of little help in issuing warning for a specific tremor. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages depending upon the area of the country. Illinois is an area where statistical methods for predicting earthquakes are often more reliable. One reason is that earthquakes centered as far west as Kansas and as far east as South Carolina have brought damage to Illinois. By monitoring the predictions based on the past history of earthquakes

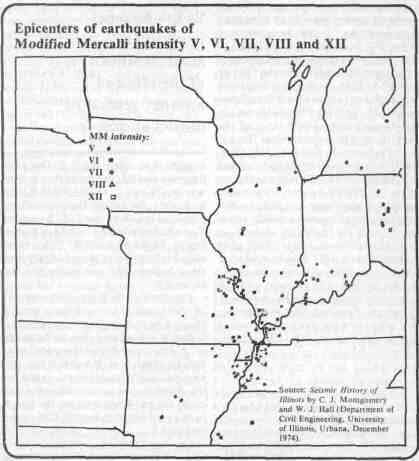

The Mercalli scale for earthquakes 20/ February 1978/ Illinois Issues we can begin to get a handle on seismic dangers for this state. Professor William J. Hall of the University of Illinois Department of Civil Engineering and his assistant, C. J. Montgomery, have compiled a report, Seismic History of Illinois. According to their report, there have been 328 earthquakes of Intensity IV or greater in Illinois from 1804-1972. Of these, 83 tremors had centers located within the state. No part of Illinois has been immune to earthquake shock waves, but the southern portion, specifically from Carbondale south to Cairo, has been especially vulnerable. A look at the map of past quakes indicates the number of high-intensity tremors which have jolted Illinoisians since 1804. The map shows only the epicenters and intensities of those quakes but not how far the shocks were felt. Intensities of earthquakes are based on a standardized scale which indicates how much force accompanies each tremor. The scale used in this case is the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale of 1931, which ranges from the least intense of I to the most intense of XII degrees (see accompanying box). New Madrid earthquake One of the most violent earthquakes in history began December 16, 1811, and was centered in New Madrid, Mo., a small town located about 35 miles south of Cairo. The shocks, which rocked an area including southeast Missouri, northeast Arkansas, southern Illinois and western Kentucky and Tennessee, lasted for more than one year. At that time, the region was sparsely settled and relatively little attention was paid to the shocks, but you can imagine the effects of a similar quake occurring today. A quake registering Intensity XII on the Mercalli scale would inflict massive damage to several large metropolitan areas, including Chicago and St. Louis. Thousands of people would lose their lives and there is no way to estimate the astronomical loss in property. Before the New Madrid earthquake subsided, it sent shockwaves throughout the United States, and damaging effects were felt in Boston and all along the east coast. The earthquake severly disturbed the Mississippi River Valley, destroying 150,000 acres of forests, tearing large holes and fissures in the ground and changing the course of the Mississippi River. Although the New Madrid earthquake was the most dramatic ever documented in this country, there have been other tremors of great magnitude felt in Illinois. A shock triggered in Charleston, S.C., on August 31, 1886, shook two million square miles and was listed as being Intensity X at its center. Other earthquakes, measuring Intensity VIII on the Mercalli scale, have rocked Illinois from centers in Memphis, Tenn. (1843); Charleston, Mo. (1895); Keewenaw, Mich. (1906); and Anna, Ohio (1937). Despite the fact that these major earthquakes were not centered in Illinois, a look at the Illinois fault system indicates why the American National Standards Committee assigned an area including southern Illinois an earthquake risk rating of three — the maximum. The committee mapped out risk areas throughout the United States for use in construction codes and planning. Most of the information on the fault map was based on statistics based on past quakes. Only six other areas in the country have received a rating of three, one of which includes the San Andreas fault along the California coast. With these risk maps and other geological data, scientists hope to achieve an effective prediction system, but much more fundamental research and field testing is still going to be required. Too many earthquakes occur in this part of the country without giving any warning. Scientists are still working to develop a reliable prediction method. The seismic picture of Illinois still befuddles geologists who puzzle over the state's extensive earthquake history. Intensity XII quakes are not common, but they have hit this area before. When asked by the Chicago Tribune one year ago about the probability of another earthquake in Illinois as dramatic as the New Madrid earthquake, Dr. Edward J. Olsen, director of the geology department at Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, answered: "There is no reason to believe it will, nor any reason to believe it will not."

21/ February 1978/ Illinois Issues

|

|||||||||||||||