By GARY ADKINS

Never defeated, he needs

Mike Bakalis takes on

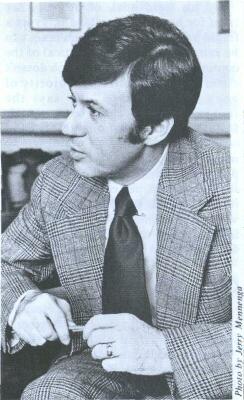

GUBERNATORIAL candidate Michael J. Bakalis seems to be keying his current campaign towards aggressive criticism of Gov. James R. Thompson. In an effort to deflate Thompson's "incredibly shallow support" (Bakalis' phrase) the Democratic nominee has flung a number of harsh charges at the style and substance of Thompson's administration. He has castigated the governor as a "do nothing," a "regal" personal spender and an "adolescent" in his dealings with the legislature. Such charges seem strangely out of place coming from a man of Bakalis' reserved professorial manners. They also seem to have done Bakalis little good — so far. Bakalis is an underdog in his race against Gov. Thompson, a position symbolized by the difference in the two men's height — Bakalis is 5 feet 10 inches tall, Thompson is 6 feet 6 inches. But like a wrestler, Bakalis is trying a lot of holds, taking the offensive and trying to pin the big man down. Thompson is a first-term governor who hasn't given voters much opportunity to get angry at him in his first year in office. He has kept his pledge not to raise taxes, taken considerable credit for pushing a "Class X" anti-crime bill through the legislature and won national attention for his tight-fisted budget and his vetoes of a bill to legalize laetrile and another to stop the state from funding abortions with welfare money. Bakalis disagreed with Thompson on both of the vetoes — and the budget too. Bakalis took a generally conservative attitude on both vetoes. He said the state "ought to be fiscally neutral" on abortions because many taxpayers do not think state money should be spent for an operation they believe to be the same as murder. Bakalis is a member of the Greek Orthodox Church, which considers abortion wrong on moral grounds. Bakalis also took the view that laetrile, a controversial drug used with questionable success in treatment of terminal cancer, should be legal. Bakalis said since there is "no evidence the substance is more harmful than any other cancer cure, an individual's choice ought to be honored in the last resort." Thompson had vetoed the abortion bill because he said it discriminated against poor women, since it did not ban all abortions, but only those paid for by welfare funds. He vetoed the laetrile bill because he said there was no evidence of the drug's effectiveness, and the state must protect the public from false drugs. The Thompson vetoes were characterized as "courageous" by the national media, and they certainly did not injure his already growing reputation as a moderate Republican governor with presidential potential. Yet they were also politically wise since they won him attention he would not have garnered had he not vetoed them. And they gained him few bitter enemies since both bills had overwhelming support in the legislature and were certain to be overridden anyway, as indeed they were. Thompson did not lobby against an override of either bill. Thus, those who liked the vetoes remember his conscientious stands that went against the odds, and those who disagreed with the stands are not angered by any lasting effect. On government interference Although both laetrile and public payment for abortions are highly emotional issues on which no leader has much hope of altering the often irrational views of both voters and lawmakers, such issues are legitimate manifestations of a philosophy of government. We must assume, of course, that both Bakalis and Thompson made their stands on ideological grounds. On both issues Bakalis came out against government action or interference. Bakalis feels "government should be 4/June 1978/Illinois Issues doing for people only those things we can't do for ourselves." While decrying such labels, Bakalis calls himself a "moderate conservative." He says that government is "a long way from the role our founding fathers gave it . . . growing in size and scope." But he doesn't believe it can be totally curtailed. He quotes a phrase of Harvard Professor Daniel Bell to describe the public's demand for services: "a revolution of rising entitlements." On Gov. Thompson Bakalis criticizes Gov. Thompson as a "do-nothing governor." He says "I don't think he [Thompson] has even begun to ask the hard questions about what functions government should do." When asked specifically what programs he would recommend be cut, Bakalis admits he is not sure, but he does feel that some departments can be combined, others perhaps eliminated. He points to the accomplishments of Gov. Patrick Lucey of Wisconsin, who, he says, generated productivity in government. Bakalis may make an issue of the size and complexity of state government and Gov. Thompson's promise to reorganize, a promise that has as yet brought little action. Other campaign issues he might raise include Thompson's backing of a pay hike for state officials, the governor's job stimulus package versus Bakalis' jobs and economic revitalization plan(see below), and the rising local assessment rates of property taxes for individuals across the state. Bakalis accuses Thompson of causing a tax increase at the local level in places where state aid to school districts is less now than in the past. Bakalis lists four main goals if elected governor. He wants to create an economic development plan, readjust funding for education, provide property tax relief and reform the medicaid system.

1. The first goal of economic development consists of a six-point program unveiled last April by Bakalis. It would give an added $100 million in bonding authority to the state Industrial Development Authority (IDA) to be used for startup loans to new businesses unable to get other financing, or for construction for lease. 2. His plan would tighten rules and standards of eligibility for unemployment compensation to prevent fraud and abuse "that presently contribute to the program's excessive cost" and eliminate excessive payments and litigation expenses in the workmen's compensation program. 3. It proposes a constitutional amendment to permit the 102 counties in Illinois to provide property tax abatement or exemptions to businesses which won't build or expand without incentives. 4. His plan would also eliminate the sales tax on machinery "used for replacement, expansion or new facilities purposes . . . beginning in fiscal 1979" (Gov. Thompson proposes a similar plan, though he does not wish to see the tax lifted on repair or replacement of parts). 5. Bakalis' economic plan also calls for phasing out the corporate personal property tax, slowly eliminating the portion of it which applies to equipment used in industrial operations. The state Constitution calls for the tax to be totally eliminated this year, but the legislature is considering a resolution (House Joint Resolution 21) aimed at deleting this mandated deadline in the Constitution through a November referendum. If the constitutional change gets on the ballot, Bakalis could conceivably campaign for its adoption. "Leave the tax as it is and collect it," he says. 6. And finally, Bakalis thinks a tax credit should be granted to business for "socially desirable goals," such as hiring unemployed or minority people, and for training unskilled and minority workers. Bakalis would also give tax credits to firms that institute antipollution or energy-saving measures.

Overall the Bakalis program resembles the governor's. Both stress the creation of jobs through improvement of the business climate. Both candidates' proposals would rely on aid to private enterprise rather than public works projects or extensive job training or state construction of roads and buildings. (Although Thompson stressed construction projects and manpower programs in his budget message, calling it part of his program for jobs creation, there was nothing massive or new about the initiatives he mentioned.) Both candidates are jockeying for position in the political center. Thompson would appear liberal to many Republicans, and Bakalis is certainly conservative for a Democrat. Both are moderates, trying to hold the votes of their party faithful and gain votes from the vast group of voters loosely classed as independents. In Illinois such a coalition is an absolute necessity for victory statewide. Bakalis' second goal, education, has not been as meticulously developed as his six-point economic plan. But he says the main point of it is "adequate" funding. He says, "The present formula is meaningless .... We should better evaluate what we're asking local districts to do and then give them the money they need to do it." He also backs the concepts of a functional literacy test as a prerequisite for high school graduation and an "early out program" for especially bright students, age 16 and over, through use of a proficiency test. June 1978/Illinois Issues/5

On his third goal, of property tax relief for homeowners, Bakalis favors a freeze on the percentage such taxes can be raised in a year. He is critical of the continued rise in the tax "which doesn't cover the overwhelming majority of people in this state." He says the increases are traceable to the state's failure to meet its pledge to fund education and the state's willingness to mandate programs for localities without paying for them. He thinks the state should put a 3 per cent ceiling on the increase of the tax from year to year, while at the same time giving money to local districts to fully fund each mandated program the state sets up. On welfare fraud Like most political candidates, he calls the medicaid system a "disgrace." (Thompson would probably agree.) "We have $300 million a year being ripped off in Illinois in fraud alone. We don't need many new laws, simply for the department (Illinois Department of Public Aid — IDPA) to do its job," he says. In January Bakalis blasted the governor and the IDPA for not catching irregularities in the billing procedures of medicaid psychiatrists. He singled out a mysterious "Dr. X" at a press conference in the Statehouse, charging that Dr. X had billed the state 31 times for working more than 24 hours in a day. He mentioned seven other psychiatrists who had also abused medicaid billing procedures and who "alone received more than one-eighth of the total Medicaid expenditures for psychiatric care" in 1976. Bakalis ended by blaming the governor for the "ultimate responsibility" in not clearing up the medicaid mess. But Bakalis greatly angered the press by not revealing the names of Dr. X and the seven other accused medicaid abusers at the press conference. Reporters felt Bakalis was making charges without properly backing them up in detail, while Bakalis obviously feared the appearance of susceptibility to slander or libel charges should he release the names. It was clear that he wanted the press to discover the names for themselves, which they eventually did, but not without residual resentment. Bakalis seems to reciprocate the media's distrust of him. When he ran for comptroller in 1976, he put forward a plan to set up a state board to oversee the press, and once in office he backed a plan to require notification of state workers whose pay records were being looked at by reporters in the comptroller's office. On school desegregation In the past Bakalis has taken some outspoken positions. In his first elected office, superintendent of public instruction, he supported collective bargaining for teachers before it was popular. He was the last elected superintendent (an office done away with by the 1970 Constitution), but the first to outline school desegregation guidelines. And Bakalis pushed for full funding of the state school aid formula before former Gov. Dan Walker decided against it in 1973. Bakalis then reversed himself to support the governor. Now, as comptroller, Bakalis has bickered with Gov. Thompson about the funds available for state services. Throughout the first months of Thompson's administration, Bakalis consistently gave a higher estimate of resources in the General Revenue Fund than the governor. Eventually, Thompson's budget estimate was proven right, and Bakalis admitted he "missed" it and said his office wasn't "prepared to make those kinds of judgments." But he later revised his thinking on this subject, saying Thompson "grossly exaggerated" the fiscal crisis in his first year in office — hiding revenues in effect, so that his "political year budget" could pay for more services. That whole subject could be a sensitive, key point in the proposed gubernatorial debates, if they ever come about. Thompson and Bakalis have agreed to a series of five televised debates, four with questioning by reporters. Originally, Bakalis wanted six debates and Thompson was pushing for four. Bakalis wanted most of the time to be spent on head-to-head discussion between the candidates, and Thompson wanted questioning by a panel of reporters. Bakalis did not mention holding any of the debates in Peoria; Thompson did and facetiously criticized Bakalis for excluding that "all-American city." Thompson wanted the first debate to be in mid-May on the budget; Bakalis did not mention a specific debate on the budget. "It is incomprehensible to me how the governor expects to carry on an intelligent discourse about the State budget without first discussing with me the substantive areas with which the budget is concerned," Bakalis said. In an interview in March, however, Bakalis criticized the fiscal 1979 budget proposals of Gov. Thompson. "It's a budget of illusions. The first illusion is that it is a low spending budget, in fact it is the largest in Illinois history. Then there is the impression it is a cost-conscious budget, but there is actually a 9 to 10 per cent rise proposed for

6/June 1978/Illinois Issues operations costs of state government. Education is called a top priority, but hundreds of school districts would get less money next year. It's described as including down taxes, yet there is going to be a raise in local property taxes all over the state." Later, Bakalis called the property tax "the Thompson tax." On the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which both Bakalis and Thompson support, Bakalis says Thompson has been "all talk." He says, "I tried to get a legislative strategy among Democrats. He was talking about ERA when he was a member of a private club that excluded women. He should do more than talk about it: he should do what he can to get votes for it in the legislature. I'm going to talk to the individual Democratic members to get their help." Bakalis thinks Thompson was "extremely lucky" to get the cooperation from Democrats in his first year on such things as the budget and Class X. "The Democratic party was in extreme turmoil after Mayor Daley died. In Chicago there was an interim mayor who needed accomplishments, there was a necessity for that kind of love feast." In reference to Gov. Thompson's much vaunted presidential ambition, Bakalis says, "That's talk that he started. He travelled out of state for 60 days and ran around the country trying to promote his candidacy. He's a self-promoter and a superb public relations man but a mediocre governor who purposely avoided tough issues. He's afraid to rock the boat, which is good politics and bad government. He has offered no leadership, only task forces and delaying actions, not true stands." On campaign technique Obviously, from such hard talk, Bakalis is a scrappy campaigner. He won his only two statewide campaigns against favored incumbents. In 1970 he upset popular school superintendent Ray Page, and in 1976 he beat hard-working Comptroller George Lindberg. But Thompson, a rising political figure in the nation, is his toughest opponent yet. Bakalis seems bent on turning Thompson's position against him, sharply criticizing his performance, thereby gaining attention. He criticized Thompson's support for a pay raise for top state executives, including the governor, by describing Thompson as a "regal" chief executive and by calling attention to Thompson's two new Checker limousines and large mansion staff. He characterized the Thompson administration as "adolescent" at the time of the dispute between the governor and some House leaders over the name of criminal justice reform legislation. Such tough language is strangely incongruous to Bakalis' own air of academic reserve and friendly introspection. He began his career as a high school teacher in Evanston in 1960 and became an assistant professor of history at Northern Illinois University in 1965. Meanwhile, he worked toward his doctorate in American history, which he received from Northwestern University in 1966. Since entering public life he has been a visiting professor at Northwestern and the University of Illinois. Few political observers believe that he can beat Jim Thompson, but Bakalis has surprised the experts twice before. He is a good media candidate, in part because of his relative youth and good looks, and in part because of his conservative, businesslike image. Regarding qualifications, he says, "I've had the experience in state government as comptroller of taking a detailed, in-depth view of all the operations of the various departments. Before that I administered a $3 billion education budget. I've had legislative experience in working with the legislature in both offices. I'm running on my record." On the debates The debates are probably a good thing for Bakalis since they put the candidates on an equal footing, by their very nature, thus lessening Thompson's advantage of incumbency. Bakalis looks as if he might be good in a debate. He knows how to come across on television, but so does Thompson. Sadly, experience has shown that performance may not matter as much as appearance. The debates are tentatively scheduled for telecast by the Public Broadcasting System. They will be held on June 9 in Springfield or Chicago, on July 25 in Carbondale, on September 6 in Rockford, on September 19 in Peoria, and on October 12, again in Chicago or Springfield. The final debate will be a one-on-one confrontation, moderated by an expert in forensics (debate). June 1978/Illinois Issues/7

|

||||||||||||||||||