|

Chicago may lose one seat

Musical chairs in congressional redistricting

EVERY 10 years, after the national census, the Illinois legislature is faced with two variations of a difficult theme: redrawing the boundary lines of the state's legislative and congressional districts.

Redistricting the state legislature in 1981 -- despite past problems (see August 1978 Illinois Issues) — will be relatively easy, compared to the problems the legislators will face in redrawing congressional district lines.

In state redistricting, the legislature will be able to work with a set number of districts, 59, and must satisfy both political needs and the Supreme Court's one-man, one-vote ruling requiring fairly equal population in each district.

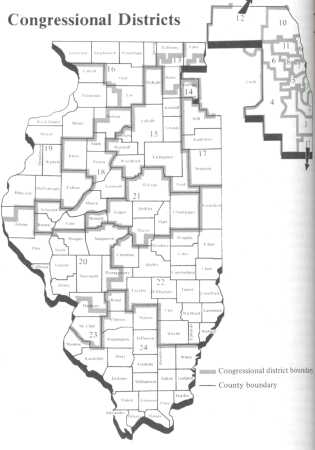

But redistricting of the U.S. House seats will be complicated by the fact that under current population projections, Illinois stands to lose one U.S. House seat, dropping the state's representation on Capitol Hill from 24 to 23 seats. That fact in turn will introduce a whole host of other factors into the redistricting battle. According to present Census Bureau projections, the population of the United States in 1980 will be 221,651,000. The bureau adds that its projections show Illinois will have 11,376,000 people at present rates of growth. But figures projected by the Illinois Bureau of the Budget show that the state will have 11,349,074 people in 1980, an increase of 235,102. That is not enough to sustain the present Illinois representation of 24 members in the House. Though Illinois' population has increased, that of other states, notably Florida and Texas, has grown faster. (For example, Georgia will have gained 500,000 people -- but no seats — by 1980.) The Illinois 24th Congressional District which should go from Chicago to its suburban belt where population has increased dramatically will go to a Sunbelt state instead.

Seats are apportioned in the U.S. House on the basis of a complex formula called the "Method of Equal Proportions." Under a 1929 law, the president transmits to the clerk of the U.S. House a listing of the number of seats each state is entitled to following every census. The clerk then sends a certificate with each state's number of seats to the governor of that state. The state's governor and legislators must then under their normal legislative process reapportion the congressional districts on a one-man, one-vote basis according to the U.S. Supreme Court decision. And the court has been very strict about variations within states from the ideal district population. In Illinois, that ideal population in 1980 is estimated to be 493,438 people for each of the 23 districts.

Reapportionment process

The reapportionment method is not simply a matter of taking the total U.S. population (221 million people) and dividing that by the 435 seats in the U.S. House. To satisfy the constitutional requirement that each state must have one representative, the first 50 seats are automatically allotted — one per state. The next 385 seats are then given priority values, according to the following formula, district by district and state by state: Each of the extra 385 districts receives a "priority number" in the Cenus Bureau calculations. That number is taken by multiplying the state's population by the formula 1-n(n-1) where "n" is each extra district by state. In other words, Illinois' 2nd district would have a "priority number" of (.707) x (11,349,074). Then all the priority numbers for all 385 districts and 50 states, are lined up in order of size and the extra districts are assigned until the limit is reached.

Political problems

All of these calculations leave Illinois legislature with a thorny political problem. Federal law mandates that the districts be equal and contiguous. It appears a simple task to take the states total population and divide it by 23 getting an ideal district population, but that same law says nothing about political tradeoffs, gerrymandering deals in the legislature or natural or historic boundaries. All of these factors may enter into the legislature's deliberations.

One key factor in drawing the new district lines will be the 24 incumbent members of Congress. Each will fight to keep his/her seat and to keep a district favorable to his/her reelection chances. The process will test the relative political clout of each member and may involve tradeoffs within the legislature. For example, Chicago regular Democrats who are not ordinarily hospitable to independent Rep. Abner J. Mikva (D, Evanston, 10th District), might agree to partitioning his district in return for the preservation of the underpopulated 1st District, now represented by regular Democrat Bennett Stewart(D., Chicago).

February 1979/Illinois Issues/4

On the other hand, the GOP could exact a price — say, endangering Rep. Frank Annunzio (D., Chicago) by extending his 11th District into the Chicago suburbs — for keeping Stewart around. These and other tradeoffs, involving the legislators, Chicago Mayor Michael A. Bilandic, Cook County Board Chairman George W. Dunne, the U.S. representatives and Gov. James R. Thompson, could keep the 1981 legislative session very busy. Another question the legislature will pattern of state legislative redistricting when it redraws the U.S. House district lines. In its own redistricting, the legislature has carefully preserved a "natural" boundary between Chicago, its suburbs, and the rest of the state. The 1970 U.S. House redistricting also followed the same pattern. But Chicago is estimated to lose more than 430,000 people, the Cook suburbs will have gained around 182,000, and the five collar counties will have gained population at a tremendous rate.

The population bulge there combined with short falls downstate as counties are moved from district to district to compensate for losses may force the legislature into breaking the "natural" boundaries. The plan outlined here keeps the Chicago "boundary" largely intact. But assigning one district each to DuPage, Lake and Will counties before disposing of their excess population will cause the encroachment of downstate districts into the suburban area. The possibility of some fantastic legislative wheeling and dealing cannot be dismissed. For instance, Chicago Democrats concerned about state money for the city, could offer to trade their chance in one or two U.S. House districts for a better break in the state legislative reapportionment. Or suburban Republicans, looking for a way to drown city Democrats within their boundaries, could offer public works projects or education aid as an enticement for downstate support. If any remnants of the "Crazy Eight" remain in the Illinois Senate after the 1980 election, their swing votes could throw another deal — as yet unknown — into the works. The possibilities are almost endless.

The legislature will face four basic problems when it redraws the lines for the U.S. House seats. The statewide

problem will be the loss of one seat, causing each district to grow by at least 30,000 people over the 1970 census figures. The other three problems correspond to the three basic regions of the state. For Cook County, the problem is whose district will be carved up. For the five collar counties (DuPage, Lake, Will, McHenry and Kane), the problem will be to dispose of their excess population after one district is assigned to each of the first three counties (see map). And for downstate, the problem is "district creep,"as boundary lines shift northward and eastward to accommodate population shortfalls-causing at least two of the downstate districts to encroach upon the suburban county belt.

Cook County

The basic problem in Cook County is simple. A 240,000-plus population loss, taken along with the nationwide shift, means that Cook is now entitled to 10 seats in the U.S. House. Presently, Cook elects 11 members of Congress and shares two others with the collar counties. However, population projections provided by the U.S. Bureau of the Census show that the Cook population loss is not evenly distributed. By 1980 Chicago will have lost over 400,000 people, and the Illinois district to be eliminated should come out of the city. The suburbs in Cook will gain approximately 150,000 people, which is enough to hold their proportion of the U.S. House seats.

Of the 400,000-person loss in Chicago, almost 70,000 of it comes out of one district alone: the heavily black South Side 1st. Census bureau projects show population within that district's boundaries will drop from 462,434 in 1970 to a 1980 mark of 393,069. With Illinois losing one seat, the "ideal" district population in 1980 will rise to a figure — according to present projections -- of 493,438. The 1st District will be more than 100,000 persons short. There are two ways to solve the problem. Both a re relatively easy numerically, but not politically. The first method is to preserve or strengthen the historic city-suburban differentiation in Cook County (see map). Under this plan, the 1st District would be eliminated, with the bulk of it going to the 2nd and 7th districts. The white-liberal 5th Ward would be tacked onto the 5th District, effectively drowning its independent voters in a sea of pro-machine votes from Bridgeport and allied areas — while keeping the 5th a majority-white area. Chicago Wards 2 and 4, now both heavily black, would be tacked onto the black-majority 7th District. The North Side districts, which have not lost as many people, would see only minor changes.

The second possible Cook County map would break the city-suburban line, but only in the north. Its predominant feature would be the elimination of the North Shore 10th District, which would be split between the 9th and the llth. This map also includes "district creep," with the avowed aim of retaining the 1st District's black majority. At the same time, it would rid the delegation of maverick liberal Abner Mikva (D., Evanston) of the 10th District. Obviously, there are political objections to both plans. The political problems with the first plan are obvious. By eliminating the 1st District, the legislature would be eliminating one of the two black representatives Illinois now sends to Washington. The GOP in the Illinois legislature may go along, but if Gov. Jim Thompson has his eye on the White House, he won't. An added attraction for the GOP state legislators, however, is the removal of all Chicago portions from the 3rd District along with the addition of Republican and heavily conservative Bloom Township to the 3rd. The result would be a now-Democratic seat turned into a second suburban battleground (along with the 10th). The second option also has its advantages and disadvantages. In addition to ridding the delegation of Mikva, that plan turns what is now a Democratic seat in the 11 th District into a marginal district. The present llth has shown GOP tendencies in the past. Gov. Thompson has carried it in both his races, President Gerald Ford carried it in 1976 and former Chicago Aid. John J. Hoellen, a Republican, almost defeated then-U.S. Rep. Roman C. Pucinski in 1966. Those tendencies would be reinforced by the addition of Maine and Northfield townships from the 10th District. Both are fast-growing areas which have formed the basis of GOP challenges to Mikva in the past. Mikva has countered with exhaustive precinct

February 1979/Illinois Issues/5

organization; incumbent llth District Rep. Frank Annunzio(D., Chicago) may not be able to do the same thing. Under this plan, the 3rd District is also marginal.

But outside of these two changes, there are no prospects for the GOP in this plan. Democratic incumbents would be safe in the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 7th, 8th and 9th districts. The 9th would become even more heavily Democratic than it already is, and it would be ready to elect an independent Jewish liberal (Mikva?) when its present Jewish liberal (Yates) retires, since the district would include all the heavily Jewish areas of the county, plus most of its independent voters in the lakefront city wards, along with Evanston and New Trier townships. An important point to note in both plans is that the GOP should be wary of any major changes in the 5th and 8th districts. It would do them no good to alienate either the mayor of Chicago, Michael Bilandic, who lives in the 5th, or the most powerful Illinoisan in the delegation, Dan Rostenkowski, who represents the 8th. In both plans the 4th and 6th districts would remain unchanged. Their population is holding up nicely, and both are safe GOP seats; nothing either party could do would make them marginal.

|

|

Both plans leave Cook with six Democratic seats, two Republican seats and two marginal seats. Ethnically, the delegation under the first plan would include one (not two) black city Democratic representatives, one city Italian, two Poles from the city and one from the suburbs, one Jewish city representative, and one Irish representative from the city and one from the suburbs. The districts in the suburbs now represented by a Jewish liberal and an Italian would be toss-ups. Under the second plan, both blacks, all three Poles and both Irishmen would be safe, as would the city's Jewish liberal. But the suburban Jewish liberal would be eliminated and both Italians would be in trouble.

The collar counties

In the collar counties, the problem is how to draw the district lines when you do not have an extra district to work with. If Illinois had not lost one seat overall, the collar county problem would be relatively simple: one Chicago district would be transferred to the five collar counties, while the 96 Downstate counties retain stable district lines. But because that district which would have been transferred will instead go to either Florida or Texas, the Illinois legislature will have a problem, and the collar counties' fate becomes tied in with that of the other 96

The problem is most acute in DuPage County. According to 1970 figures, the 14th District, which includes all but a few precincts of DuPage, had a population of 464,029. That census also showed DuPage had a total population of 491,882 — only 1,556 less people than the number needed for an entire district in 1980. By 1980 DuPage will have gained almost 120,000 people, according to population projections. Where to put the excess is a knotty problem which the legislature will have to solve. One possible solution, based on projected 1980 population figures, follows: District 12, with 19,059 less than the ideal district population in 1980, gives up its part of Lake County to District 13 and splits Kane County with District 13 District 13, with 42,688 more population tion than the district ideal, adds one fifth of McHenry County rather than its

|

February 1979/Illinois Issues/6

present one-half (29,872 people in that portion) to all of Lake County. District 14, with 89,586 population (not counting the portions of District 6) more than the ideal, gives up one-sixth of DuPage County to District 12 to replace the 12th's loss of its part of Lake Count District 15, with 26,056 population below the ideal, divides Kane County in half with the 12th District. District 16, with a 1980 population of 450,711, or 42,727 below the ideal, takes 80 per cent instead of 50 per cent of McHenry County, leaving the rest of McHenry for the 13th District. Though these solutions are tentative, they do illustrate the problems the legislature will have. Strictly speaking, the 15th and 16th districts have no place in a discussion of the five collar counties. But because these two districts must lose people to other Downstate districts which need to make up population shortfalls, the net result is that they wind up encroaching upon the collar county area. Though the solidly Republican political complexion of the two districts is not likely to change, the type of Republican sent to Washington -especially from the 16th — may do so. The other changes are relatively easily explained — though not as easy to work out. Lake County is close to qualifying for an entire district based on its population. To simplify things, it could be given a district which it would dominate while the McHenry County portion would only satisfy population requirements.

The 14th District would include only 84 per cent of DuPage County — which is all it needs. The excess DuPage population, combined with the westerly Cook townships now in the 12th District, would make up a new 12th District. Philip Crane (R., Mount Prospect) or his successors, should have no trouble there, and any Democratic votes produced in Elgin (which this year produced its mayor as the challenger to 13th District Rep. Robert McClory) will be drowned. Also added to the 12th would be that portion of Kane County not needed for the 15th District's population requirement.

In the 17th District, Will County would find itself in the dominant position. Though it will still be around 100,000 people short of qualifying for a full district, its growth should enable it to shed Bloom Township. Downstate shortfalls will rob the 17th of half of Iroquois County, effectively turning the 17th into the Will County district. Incumbent Rep. George M. O'Brien (R., Joliet) wouldn't mind, since he has represented the area for years in both the state and national legislatures. But 3rd District Rep. Marty Russo (D., South Holland) would not particularly appreciate the addition of heavily Republican Bloom to a district which former Illinois House Speaker W. Robert Blair (R., Park Forest) had originally carved out for himself.

Downstate

"District creep" will be the dominant feature of the new lines which could be drawn outside the Chicago area (see map). Though every district outside Chicago and the collar counties gained population, only one gained enough to match the "ideal" population of 493,438. This district is the 15th which is "blocking the road" for several districts which have projected shortfalls in population. As a result of subtractions from the 15th to equalize those shortfall districts, the 15th would have to move more strongly into Kane County than at present.

In the collar counties, where to put the excess is a knotty problem,

while 'district creep' will be the dominant feature of new lines

which could be drawn outside the Chicago area

|

The district with the least change is the Downstate 24th. The counties it encompasses will have grown by 23,798 people, according to population projections for 1980. This would mean only a 4,623-person shortfall, and the district would need to take only 60 per cent of tiny Edwards County from the 22nd to make up the difference. The change would have absolutely no effect on the prospects of Rep. Paul Simon (D., Carbondale).

On the other hand, a shortfall of over 29,000 people in District 23 could set off a "domino effect" pushing the boundaries of districts 19 and 20 northward, those of districts 16 and 21 eastward, those of 15 into Kane County and significantly altering the boundaries of District 18. The 23rd District has experienced the slowest growth of any Downstate district, adding a net of only 960 people by 1980 to its 1970 population of 462,920, according to population projections. The 23rd could not expand southwards or eastwards without causing substantial problems in both the 24th and 22nd districts. To balance the 23rd's population will take fully four-fifths of Madison County's population, rather than one-half. But taking 29,558 people from the Madison portion of District 20 would cause the shortfall there to rise from a modest 8,125 to a much higher 37,000-plus — and that shortfall would set off a game of musical chairs among counties along the Illinois River.

With other population gains and losses in District 20 thrown in, major additions would be needed. Rep. Paul Find-ley's west central district would have to make up its shortfall by grabbing, under this tentative plan, the rest of Adams County from the 19th District, and three Illinois River counties (Brown, Cassand Schuyler) and part of another (Mason) from the 18th plus another river county (Menard) from the 21st. The changes, all in a northward direction, would expand this old amalgamation of one Democratic and one Republican district - an uneasy marriage consummated after the 1960 census — into more securely Republican territory north of the river. If Findley ever retires, the seat should stay in GOP hands; under the old lines, it would be marginal.

In the east central area of the state, the present 21st and 22nd districts are both projected to fall more than 10,000 persons short of the 1980 ideal district population. If the 20th District took Menard County from the 21st District, the shortfall in the 21st would rise from 15,500 to 27,700. Since further chopping away at Bob Michel's 18th District seat is unthinkable for a GOP governor, the 21st would have to move northeast to equalize its population, taking Ford County (14,318 projected population) and one-third of Livingston County (13,417) from the 15th District. The result of that loss for the 15th, would be to push it more deeply into Kane County in the Chicago suburbs.

On the eastern side of the state,

February 1979/Illinois Issues/7

Rep. Dan Crane's (R., Danville) 22nd District will have a 11,703-person loss by 1980 and would be minus 4,623 more people if part of Edwards County goes to the 24th. Since the Will County dominated 17th District in the Chicago suburbs will have more than enough population and the 22nd just south of it too little, the best solution may be to split sparsely populated Iroquois County between them. Tom Railsback's (R., Moline) 19th District will have a population shortfall of 18,131 within its present boundaries by 1 980, according to population projections. Taking a corner of Adams County from the 19th to add to Findley's 20th District would increase the shortfall to 29,599. The easy solution is to add a corner (3 per cent and 2,202 people) of Knox County from the 18th and the rest of Lee County (27,397) from the 16th to the 19th District. It shouldn't affect Railsback politically.

|

Following the 1970 census, the two houses of the legislature disagreed,

and the issue wound up in the courts . . . the courts may again have to

disentangle the legislative knot

|

The representatives which such additions would affect are John Anderson (R., Rockford) in the 16th District and Robert Michel (R., Peoria) in the 18th District. Under this tentative plan, Michel would lose a corner of Knox County to the 19th, three river counties (Schuyler, Brown and Cass) and part of another (Mason) to the 20th. These losses would increase the shortfall for his district from 9,216 to 43,469. For his district, as for the 21st, there would be only one way to go: northeast into the 15th. Taking Marshall and Woodford counties would add 44,017 people, according to the population projections, and would further push the 15th into Kane County.

As for Anderson, his 16th District would remain solidly Republican, but the nature of the GOP electorate might be changed. With the addition of most of what would be left of McHenry County, which is both fast-growing and conservative, the base for future challenges to Anderson's moderate Republicanism would be expanded. Losing Lee County to the 19th would be a loss to Anderson of his home turf, but a gain of McHenry could very well be a mecca for the Rev. Donald Lyons, Anderson's challenger in the last primary.

Conclusion

There are several tentative conclusions which can be reached about the 1981 redistricting. The most obvious one is that the delegation may become preponderantly Republican. With the Republican stronghold in the Chicago suburbs gaining people at a rapid rate, the suburban representatives will become even safer for the GOP than at present. Encroachment of the 15th and 16th districts into the suburbs will also strengthen the GOP character of those two districts -- and, given the more conservative Republicanism of the Chicago suburbs versus the rest of Illinois, may endanger moderate Republican John Anderson's hold on his 16th District.

"District creep" downstate will also solidify GOP strength. The 20th District trict, which now straddles a Republican north-Democratic south dividing line in the middle of the state, will move northward, making the district a safe seat for any GOP representative, not just moderate Paul Findley. Moving the boundary of the 22nd District north ward into Republican Iroquois County may also turn a now marginal district into a safe GOP seat. And changes in the district lines in Kane County, caused by a northward shift of the 15th District may eliminate any strong base for s Democratic challenge to present 13th District Rep. Bob McClory or his successor. In Chicago and Cook County, the re districting is sure to eliminate one seat now held by a Democrat and endanger one or two others. The seat that goes will either be — under the tentative plans the safe 1 st Distrct or the marginal 10tg District. In both plans, the addition of heavily Republican Bloom Township the 3rd District will endanger the chances of Rep. Martin Russo. And one of the plans may very well imperil 11th District Rep. Frank Annunzio throwing him into an unfamiliar, suburbanized Republican-leaning district. The Illnois House delegation, which was 13-11 Democratic as recently as 1975, and is now 13-11 Republican, could be 14-9 Republican in 1983 after the redistricting.

There is one other conclusion could be drawn: "the past is prologue." Following the Supreme Court's one man, one-vote decision in 1964, the legislature could not redraw the lines and a special commission was mandated to do so. Following the 1970 census, the two houses of the legislature disagreed, and the issue wound up in the courts With both a state redistricting and a complex U.S. House seat redistricting battle occurring simultaneously, and with a legislature split between the parties and a GOP governor, the prospect is likely that the courts may have to disentangle the redistricting knot again.

February 1979/Illinois Issues/8

Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library

|

|