The vote power of Chicago Democrats from Cermak to Bilandic The consolidation of clout "PROHIBITION In 1920, Chicago had a Republican mayor, strong GOP city council representation, several competing Republican organizations inside the city and a tradition of voting heavily for Republican national and state candidates. In fact, 1920 GOP presidential candidate Warren G. Harding swamped Democrat James A. Cox in Chicago 549,243 to 182,252. Cox could carry only two city wards. The Democratic gubernatorial candidate, J. Hamilton Lewis, won just seven wards, and the county Republican ticket crushed their Democratic foes inside the city. Today, nearly 60 years later, the Chicago Republican party is a lifeless hulk unable to field viable candidates for major city office. In 1975 and 1977 its mayoral candidate was unable to carry one city ward. In 1976 its presidential candidate received less than one-third of the city vote. How has this come about and could the party's political demise have been avoided? This article will analyze the themes and trends which have left the Republican party so devastated and the Democratic party so dominant inside Chicago. We will discuss demographic shifts inside the city and migration patterns in and out of Chicago; the building of the Democratic organization and the destruction of the Chicago GOP; the impact of independent and black political activity and, finally, the influence of certain individuals who have shaped Chicago politics as we know it today. The 50-ward systemPrior to 1921 Chicago was divided into 35 wards. Each ward had two aldermen elected in alternate years to two-year terms. Aldermanic races were legally partisan contests requiring a party primary, and Chicagoans faced a constant barrage of ward elections. Beginning in 1912, Chicago's reformers advocated a redistricting of the city's ward boundaries. They believed the faster growing peripheral areas (containing the largest number of reform and independent voters) should have greater representation in the city council. Reformers advocated four-year terms and nonpartisan aldermen. They also wanted the wards to be single-member districts which would reduce council membership to a more manageable 50. According to the Municipal Voters League, a new 50-ward city council would give independent citizens acting in groups a rare opportunity to clean house. But as is often the case in such "reforms," the politicians (in this case, city Democrats and Republican Mayor William Hale "Big Bill" Thompson) manipulated the change to fit their own needs. The outcome of the "reform" was a system, still in use in 1979, in which each of Chicago's 50 wards elects an alderman to serve on the city council for a four-year term. The nonpartisan elections are held in February; however, if no candidate gets over 50 per cent of the vote, a runoff is held in April between the two top vote-getters. The February elections coincide with the Republican and Democratic mayoral primary elections; the April runoffs are held simultaneously with the mayoral general election. Chicagoans will be at the polls on February 27 and on April 3 to elect a mayor and city council to serve for the next four years. The 50 Chicago wards have been redistricted a number of times since 1921, and a ward-by-ward analysis of Chicago politics since then must consider these boundary changes. An examination of these changes reveals two crucial facts. First, except for wards 20, 21 and 34, which were moved to the south side to accommodate the growing black population, the boundaries of most city wards have not changed much since 1921. The major change has occurred to follow the population which has shifted outward towards the city's periphery; thus central city wards have grown geographically larger and peripheral wards have become territorially February 1979/Illinois Issues/11 smaller. Second, because only parish loyalty outranks ward loyalty to many Chicagoans in locating and identifying one's neighborhood, socioeconomic status and political persuasion, Chicago politicians have not often tampered with the numbers placed on city wards.

February 1979/Illinois Issues/12

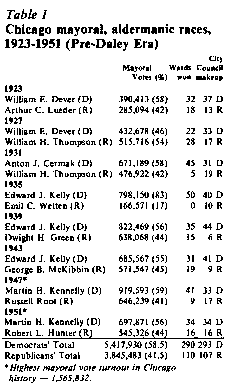

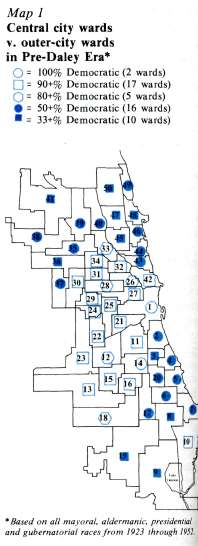

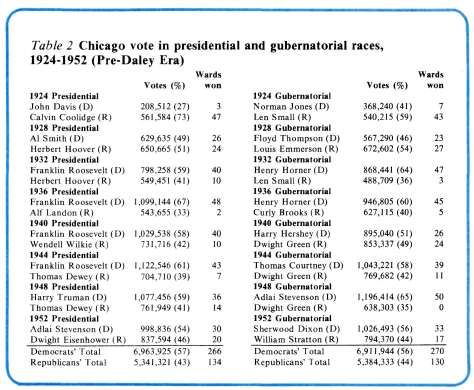

elections in the city. Among the factors causing this were the personalities of various candidates, the incredible cross-party factional deals and the stronger local Democratic inner-city ward organizations. The most crucial factor influencing this vote differentiation, however, was voter turnout in peripheral wards. In both local and national elections, central city ward voters turned out in relatively equal numbers, but the vote in the outer GOP wards was far heavier in national and state elections than it was in mayoral or aldermanic contests. Breakdown of a patternThis pattern broke down in 1931 when Cermak, the personification of an inner-city ethnic leader, crushed Thompson in traditional GOP peripheral wards. Republicans demonstrated their anger with Thompson by turning out in record numbers for a mayoral election. One year later Franklin D. Roosevelt, aided by a strong peripheral ward showing, became the first modern Democratic presidential candidate to carry the city. These two elections broke political traditions. In subsequent years Republicans would regain some of their power base on the periphery, and their candidates would once again carry these outer wards, but never again would the margins be as great. The Democrats had broken the peripheral barrier; psychologically and geographically they were expanding out from the center. Aiding the Democratic upsurge at this time was the nationwide Depression. Undoubtedly economic conditions spurred voter interest in the inner-city wards. FDR's candidacy encouraged a huge turnout in the heavily Democratic central ward region. But the Democratic trend locally had been set in motion prior to the Depression. Another factor fostering a Democratic upswing during this crucial 1927-1932 period was the consolidation of the Democratic organization under Cermak. His political rise came just when Chicago Democrats were emerging from decades of intraparty factional fights. Contenders for party control had not divided along ethnic lines; rather, ward leaders sought alliance with those groups which gave them tangible benefits. Cermak moved from Cook County Board president to party chairman and mayor with the backing of the same Irish and non-Irish ward bosses who had supported previous Democratic leaders. Some Irish Democrats opposed Cermak's election because of their anger at being bypassed within the party hierarchy. Cermak's Bohemian ancestry and his close ties with the city's Polish and Jewish spokesmen did, of course, bring more non-Irish into leadership positions within the party. But to say it was a revolt against the Irish overlooks the fact that Cermak's two most important backers were Pat Nash and Joe McDonough, and denies the fact that after Cermak's death Edward J. Kelly was selected as his replacement by Cermak's strongest non-Irish supporters. This logic would suggest that in 1979, Chicago's Irish ward committeemen will support Mary Jane Byrne over Michael A. Bilandic for ethnic reasons. Cermak was the first Democratic mayor ever to have been a ward committeeman (Daley was the only other one). During his brief tenure as mayor and party chairman, Cermak intertwined political and governmental processes and made them almost inseparable. Under Cermak the loosely linked parts of the political organization were rearranged and then consolidated into a well-oiled machine. Kelly and then Martin H. Kennelly followed Cermak into the mayor's office. The 1943 Kelly-George B. McKibbin race was a close contest. Mc-Kibbin, a prominent GOP lawyer, received 45 per cent of the vote and won 19 wards. The remaining Republican strength was still holding on the perimeter of Chicago. This fact did not escape the Chicago Tribune: "the wards carried by McKibbin fringe Chicago on the south side in Hyde Park, Englewood, and the Beverly Hills area. He carried wards in the northwest which are largely residential. On the north he carried six of nine wards. His strength was shown along the Lake Shore wards from Lincoln Park to Evanston. . . ." A ward-by-ward recapitulation of mayoral and aldermanic races during this 1923-1952 period reveals the extent of the Democrats' inner-city strength: 25 or one-half of the city wards voted Democratic for mayor or alderman 75 per cent of the time. Twelve wards (1,13, 14, 15, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 29,32,42) were Democratically perfect; no Republican was able to carry them in any aidermanic or mayoral contest. The best GOP ward was the 47th - a heavily German northside ward and the home base of the Hoellen family. John Hoellen, Sr., and his son John Hoellen, Jr. (Daley's 1975 opponent), occupied  February 1979/Illinois Issues/13 the ward's aldermanic seat for most of the past five decades. The 47th supported Democratic candidates only one-third of the time, but politically it was a rather lonesome ward in the city. Only seven other wards (3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 41, 15) joined the 47th in not voting for Democrats at least 50 per cent of the time. Presidential and gubernatorial elections: 1924-1952 Republicans fared slightly better in presidential and gubernatorial elections than they did in mayoral and aider-manic contests from 1924 to 1952. Still, GOP presidental and gubernatorial candidates won only 33 per cent of ward races, 233 of 800, and like their mayoral candidates were unable to carry the city following the critical 1927-1932 period. In 1940 Dwight H. Green, a Chicagoan and a recently defeated mayoral candidate, gave the GOP their best showing by coming within a few votes of carrying Chicago against Harry B. Hershey in the governor's contest. As in local elections, Republicans did better in national and gubernatorial races in the city's peripheral wards. Here the higher income and more heavily Protestant Chicagoans supported GOP presidential and gubernatorial candidates in the 1920's, switched to FDR and Henry Horner in the 1930's, and came back somewhat to the GOP fold in the 1940's and in 1952. Of course, Republicans on the periphery, like the rest of their fellow Chicagoans, rallied to the banner of Democrat Adlai E. Stevenson II in 1948 to blitz incumbent Gov. Green, who was seeking his third term. During the decade of the 1920's Chicago's population jumped from 2,701,525 to 3,373,573. The overwhelming bulk of this 672,048 increase occurred in 10 periphery wards (7, 8, 15, 19,37, 39,40,41,49,50) which saw their populations double during the decade. Irish, Poles, Jews and East Europeans who could afford to leave their old inner-city neighborhoods were moving to more desirable areas on the city's periphery. Eleven wards, mainly on the periphery, voted for Republican presidential and gubernatorial candidates over 50 per cent of the time. For example, the 19th Ward (Beverly) on the city's far south side was the best GOP ward, supporting every Republican presidential candidate from 1924 to 1952. Only Horner in 1932 and Stevenson in 1948 were able to carry this ward for the Democrats.

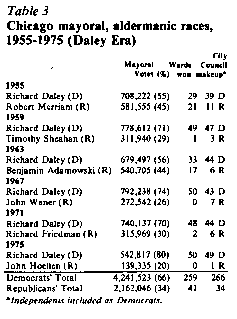

The Daley yearsIt was at the time of Daley's emergence as Democratic leader that the full impact of black Chicagoans hit the local political scene. As previously discussed black Chicagoans generally supported the Republican party and specifically backed "Big Bill" Thompson earlier in the century. They remained incredibly loyal to Thompson throughout his political life. But "Big Bill's" career ending mayoral defeat in 1931 plus the Depression gave the Democrats a chance to make inroads. Throughout the 1930'sand 1940's Chicago received increasing numbers of black migrants. Most settled in the city's southside black belt which began to bulge beyond its 2nd and 3rd ward borders, where black aldermen had represented black people's interests for over 20 years. In 1947, a new southside 20th Ward was carved out to give the city's burgeoning black population a third alderman. Democrats in national and state elections had already turned around the city's black wards by 1940, but in mayoral elections the two top-heavy black wards were battlegrounds. In 1940, William L. Dawson, anambitious black lawyer and former GOP 2nd Ward alderman, switched to the Democratic party and was elected 1st District congressman. By 1955 Bill Dawson was the city's undisputed "Black Boss," able to deliver five south side wards (2,3,4,6, 20). When Dawson teamed with Daley's February 1979/Illinois Issues/14 troops in 1955 he found the man and the vehicle to make the black vote a lifeline of the Democratic party. This alliance eliminated a vital part of the city Republican coalition and further diminished the GOP chances for a comeback, It also gave Daley a chance to demonstrate his political acumen by showing that it was possible to incorporate blacks into a multiracial, urban political organization. Much has been written about Daley as a politician, but seldom is it pointed out that his black connection was a key to the Chicago political machine outlasting America's other big city machines. Daley worked with blacks the same way earlier bosses had dealt with other large ethnic groups entering the political process. He gave them status, local office, upward mobility, neighborhood autonomy and the economic rewards for loyalty. Though his white and black critics may scoff, Daley also helped blacks attain political power and sold this power sharing arrangement to his own own white ethnic allies, Only late in his extraordinary career did Daley have to cope with the race problems which had destroyed other Democratic organizations around the country. Chicago's ghetto riots, Dr. Martin Luther King's housing marches, the Black Panther shooting episode, former Cook County State's Atty. Edward Hanrahan, a growing black independent middle class, Congressman Ralph H. Metcalfe's break over police brutality, and voter apathy among poor blacks combined to challenge Daley's brand of white-black politics. Yet even now, after the deaths of Daley and Dawson, their successors are still taking on all comers in south and west side black neighborhoods, producing many more organization victories than setbacks. City elections: 1955-1975

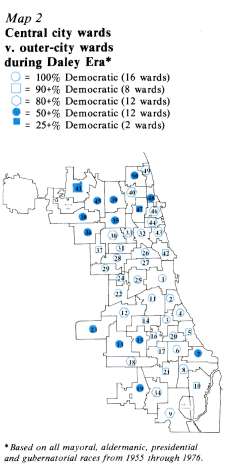

Daley and the Democratic party's desire to expand their party to include Chicago's periphery did not come at the expense of their long-time power base, the inner city. A ward ranking of Daley's vote margins in his six elections shows them the undisputed backbone of the city's Democratic party. Only in the 41st Ward on the city's far northwest side did Daley lack an overall plus-vote margin. The 41st is also the only ward where Daley merely broke even in his six elections. In 11 other wards he was 4-2, in 16 others he lost only once, and in the remaining 22 wards Daley was undefeated. The voting trends of Daley's six elections disclose some startling internal shifts within the Democratic organization. First, the 11th Ward's unmatched preeminence in Democratic politics is a relatively recent phenomenon. In Daley's first three mayoral races the 24th Ward easily outstripped the 11 th in support of the mayor. Moreover, several other west side wards were about even with the 11th Ward in producing Daley vote margins. In 1967 the 11th took off, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

February 1979/Illinois Issues/15

| and in 1971 and 1975 it shot out of sight. Second, the same westside wards (including the 24th) did not produce the boxcar margins in 1975 that they delivered in 1955. The west side underwent dramatic racial change and suffered a huge out-migration of total residents. The new black Democratic leaders have not matched the margins of old Jewish, Irish and Italian ward leaders. The westside's loss of political clout is probably the most dramatic change within the Democrat organization during the Daley years. On the other hand many southside wards which underwent racial change during the Daley Era have maintained or greatly improved the Democratic margins. Wards 6, 7, 8, 17, 20, 21 (and the new entry 34) have and will produce the city's black political leaders. They have bypassed the older and poorer southside black wards (2, 3, 4) in vote turnout, social and economic status and influence in the Democratic organization. The aldermanic contest mirrors the mayoral races during the Daley Era. The Republicans were respectable in 1955 and nonexistent by 1975. Like Daley, regular Democratic aldermanic candidates had more trouble with other Democrats than they did with Republicans. The independent aldermanic movement crested in 1971. Stretching out from their base in the north side lakefront wards, independents mounted strong challenges against regular Democrats in 20 city wards. Singer (43) and Richard Simpson (44) were successful on the near northside; Leon Despres (5) and William Cousins (8) won on the southeast side; Father Francis Lawler (15) and Anna Langford (16) beat regulars for different reasons in the racially tense southwest side; and former regular and County Board President Seymour Simon (40) converted to the independent cause. In sum, the Daley years saw the Democrats bury their opposition in mayoral and aldermanic contests. Twenty-one wards were perfect for the Democrats (6 mayoral and 6 aldermanic victories), and 45 wards elected Democrats in these elections 75 per cent of the time. The Republicans carried only 12 per cent of these total ward contests, and only the 47th Ward voted Republican more than 50 per cent of the time. Daley consolidated Chicago's government under his control by eliminating organized political opposition. |

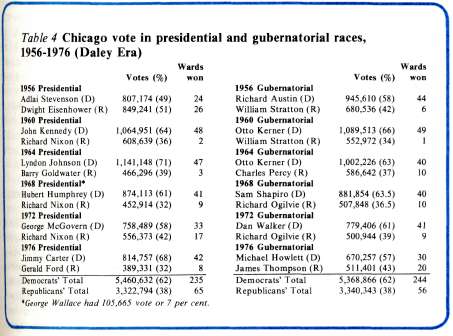

Presidential and gubernatorial elections: 1956-1976

Democratic presidential and gubernatorial candidates did well in Chicago during the Daley years, 1956-1976, but their performance did not match that of the local candidates. Of the 600 total ward contests in six presidential and gubernatorial elections during this period, the Republicans carried 121 or 20 per cent of the individual ward battles. Thirty-nine wards (compared to 45 in local elections) supported Democratic presidential and gubernatorial candidates 75 per cent of the time. Seven peripheral wards (compared to one in local elections) supported Republicans more than 50 per cent of the time. Surprisingly, the 41st Ward was a perfect Republican ward in presidential and gubernatorial elections. These peripheral wards continue to support some of the most popular Republican candidates like Gov. James R. Thompson, who carried 20 wards in 1976. Despite the remaining traces of Republican support which show up in the votes for Thompson, Atty. Gen. William J Scott, or U.S. Sen. Charles H. Percy, it is not likely that any Republican in the near future can carry 26 wards and attain a city plurality as did Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1956.

On the other hand, Daley's power in determining state and national winners in Illinois dwindled as Chicago's population dwindled (see "Downstate holds the key to victory," February 1978), John F. Kennedy in 1960 and Lyndon B, Johnson in 1964 received over a million votes in Chicago. Gubernatorial candidate Otto Kerner in those same years also captured over one million city votes. But in the 1970's these Chicago vote totals dropped for presidential and gubernatorial candidates even though the percentages stayed approximately the same or were even higher in some cases. Undoubtedly Daley's greatest moment in presidential politics was in 1960 when Chicago had enough votes to move Illinois into Kennedy's column. In 1976 Daley pushed hard for Jimmy Carter and even though Carter received approximately 4 per cent more of the city vote than JFK, his vote margin was 30,886 less and he lost the state.

When Daley died in 1976, his Chicago Democratic organization was not about to topple. Rather, it was at the zenith of its electoral political power in the city. The congressional scorecard stood Democrats 7, Republicans 0 (the last Republican city congressman had been elected in 1956); the state Senate Chicago delegation was Democrats 20, Re-publicans 0 (the last state Senate city Republican had been elected in 1972) in the Illinois House each of Chicago's 20 districts had two Democratic members (the last time a city district elected two Republicans was in 1968); the city council included only one Republican, and no Republican had served as mayor since 1931.

The Post-Daley Era

Richard J. Daley's death on December 20, 1976, did not alter the style or substance of Chicago politics. The politics of Chicago remains within the ranks of the regular Democrats. Personal ambitions, ethnic loyalties, geographical alliances, policy issues, friendships and animosities fuel conflict in Chicago as elsewhere, but these battles are largely confined within a general consensus

February 1979/Illinois Issues/16

that party unity is desirable and that the Democrats should govern Chicago.

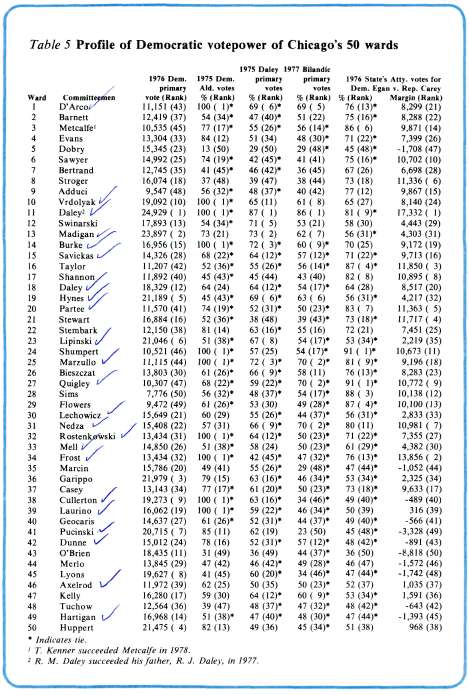

One way to look at the Democratic party's internal politics is to observe the records of its 50 ward committeemen in producing votes to bring election victories to the party. According to Milton Rakove in Don't Make No Waves. . . Don't Back No Losers, "The position of ward committeeman carries with it not only prerequisites but also responsibilities. . . . If one is given a leadership position by the party, one is expected to lead and product or get out. There is little room in the relationship of the ward committeemen to the county central committee for sentiment, friendship, or failure. Powerful committeemen who have been high in the party hierarchy for many years have been cast aside when they lost control of their ward organizations or failed to deliver for the party in an election."

Table 5 takes a close look at the current 50 ward committeemen and their performance in five recent key elections: the 1976 Democratic primary, the 1975 aldermanic elections, the 1975 and 1977 mayoral primaries, and the 1976 contest for Cook County state's attorney, which was a high priority race for the Democratic party. In each instance, a ward's performance score is shown and ranked against the other 50 wards (see following page for table 5, "Profile of Democratic votepower of Chicago's 50 wards").

| "The 1976 primary with Michael J. Howlett v. Daniel Walker for governor and Metcalfe v. Erwin A. France for Congress produced a high turnout. The ward committeemen were elected in this election for their current four-year terms, and their power within the party is based on the number of Democratic votes cast in their ward. Column 1 shows the ward rankings in the 1976 primary. Daley's 11th Ward ranked first with 24,929 votes cast, and Isaac Sims' 28th Ward finished last with only 7,776 Democratic ballots. Perhaps the most obvious pattern here was the poor turnout in the 15 black wards. Only three finished in the top half (21st, now led by Congressman Bennett Stewart; John H. Stroger's 8th Ward and Eugene Sawyer's 6th), and eight of the bottom 11 were black wards (3rd, 16th, 17th and 20th on the south side; 24th, 27th, 28th and 29th on the west side). Another interesting feature of the 1976 primary is the strong showing of the wards on the periphery of the city. With the exception of Daley's 11th Ward, everyone in the top 10 is on the periphery of the city: Michael J. Madigan's 13th, Louis P. Garippo's 36th, Jerome Huppert's 50th, Thomas C. Hynes' 19th, William Lipinski's 23rd, Roman C. Pucinski's 41st, Thomas G. Lyons' 45th, P. J. Cullerton's 38th and Edward R. Vrdolyak's 10th. Comparing ward turnout in Democratic primaries in 1972, 1974,1976 and 1978 shows the emergence of three committeemen who have rapidly improved the rankings of their wards Lipinski (23 rd Ward) up 27 ranks from 31st to 4th; Richard Mell (33 rd Ward) up29 slotsfrom41stinl974to 12th,and Edmund L. Kelly (47th Ward) up 21 notches from 29th to 7th. The second column on table 5 shows the vote percentage attained in each ward by the regular Democratic candidate for alderman in 1975. A good ward committeeman should be able to deliver an easy victory for his aldermanic choice, and as noted earlier 40 committeemen produced victories and 29 of them got 60 per cent or more for their aldermen in 1975. Six more regular Democrats won in runoffs in the 5th (which now has the only independent committeeman), Joseph G. Bertrand's 7th, William H. Shannon's 17th, Hynes' 19th, John C. Marcin's 35th and Lyons' 45th. Losing their wards to an independent or a Republican in the 1975 runoffs were Stroger's 8th, Daniel P. O'Brien's 43rd, John Merlo's 44th and Martin Tuchow's 48th. The next two columns of table 5 show a similar pattern for the 1975 and 1977 mayoral primary victories by Daley and Bilandic. The showing of the southwest side bloc of five wards may indicate the new core for organization support. These five best in 1975 include Daley's 11th, Theodore A. Swinarski's 12th, Madigan's 13th, Edward M. Burke's 14th and Vito Marzullo's 25th. These elections are discussed later. The last two columns show the vote percentage and vote margin attained by Democrat Edward Egan in his losing battle for Cook County state's attorney in 1976 against Republican Bernard Carey. This vote is the best recent test of a determined Democratic organization effort against an attractive, well-known Republican in a county race. Carey was able to win 11 wards by percentages |

February 1979/Illinois Issues/17

|

ranging from 51 to 55, except for the 43rd Ward where he won 64 per cent of the vote. Nine of his winning wards were among the 17 wards north of North Avenue. The committeemen who failed to carry their wards for Egan were Marcin (35th), Cullerton (38th), John Geocaris (40th), Pucinski(41st), George W. Dunne (42nd), O'Brien (43rd), Merlo(44th), Lyons(45th), Tuchow (48th) and Neil F. Hartigan (49th).

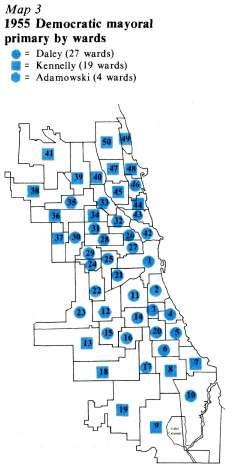

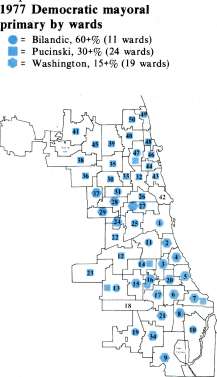

At the other end of the scale are those wards which produced the biggest percentages and more importantly, largest margins for Egan. Here the value of the black wards to the Democratic party in contests against the Republicans is clearly demonstrated. In terms of vote margins, 12 of Egan's best 14 wards were black including Wilson Frost's 34th, James C. Taylor's 16th, Stewart's 21st, Cecil A. Partee's 20th, Stroger's 8th, Shannon's 17th, Edward A. Quigley's 27th, Sawyer's 6th, Walter L. Shumpert's 24th, Sims' 28th, Willie Flower's 29th and Ralph Metcalfe's 3rd. Overall, the 15 black wards produced a 155,658-vote margin for Egan, while the other 35 city wards produced a cumulative margin of only 130,373. Although blacks do not turn out in large numbers for their committeemen those blacks who do vote are very loyal to the Democratic party and account for a crucial part of the huge victory margins which Democratic Candidates coming out of Chicago bring with them for county, state and national office. Chicago's other sizable minority, the Latin community, is already large and rapidly growing. The 1970 census showed Chicago having nearly 250,000 Spanish-speaking persons, although the true number is much higher. At present however, the Latin community is with out political power. There is not yet a single Latin alderman or ward commit-teeman because the Latins do not vote Many are not citizens, others suffer from language barriers. Potentially though, the Latin population is a power-ful political force in Chicago, particulary-ly in west side, near northside and north lakefront wards. Potential oppositionThe most recent mayoral primaries of 1975 and 1977 reveal the major divisions within the Democratic electorate of Chicago. These divisions are essential in understanding the politics of the city. In 1975, Mayor Daley was seeking his sixth term in office. He was challenged by independent Alderman Singer (43rd) and black state Sen. Newhouse. Citywide, Daley won 57 per cent, Singer 29 per cent and Newhouse 7 per cent. Daley won 47 wards, Singer captured 3. Former State's Atty. Hanrahan was also in the race. In 1977, then-Acting Mayor Bilandic won 51 per cent of the vote against northside Polish Alderman Pucinski, who received 32 per cent, and another black state senator, Harold Washington, who gathered 10 per cent citywide, and three other candidates including Hanrahan again. Bilandic carried 38 wards, Pucinski 7, Washington 5. The accompanying maps of these two elections give a rough approximation of the location of white ethnic (especially Polish) voters - Pucinski's supporters; liberal independents - Singer voters; the black electorate - Newhouse and Washington voters; and regular Democratic organization voters - Daley and |

|

February 1979/Illinois Issues/18

| Bilandic voters. Even a quick glance at these maps reveals the basic geographical patterns of Chicago voting the northside and southwest side white ethnics, the "lakefront liberals," the south and west side blacks and the central city core of Democratic organization support. Pucinski in 1977 was, and still is, the alderman and committeeman of the 41 st Ward. Previously, he served 14 years in the U.S. Congress representing the northwest side. The Pucinski vote in 1977 reveals both a strong north-northwest side appeal and the pull of ethnic Polish ties to his candidacy. In the 17 wards mostly north of North Avenue, Pucinski won over 30 per cent in each, and he actually carried seven of them. In fact, his totals were so strong that only in Kelly's 47th Ward was Bilandic able to surpass 60 per cent of the vote. These 17 wards north of North Avenue frequently support popular Republican statewide candidates like Gov. Thompson and Atty. Gen. Scott, although they support Democratic candidates in local elections. In the other 33 city wards, Pucinski was able to climb above 30 per cent in only the 7th, which includes heavily Polish neighborhoods; the 26th, adjacent to his north-side stronghold, and five southwest side wards(12th, 13th, 14th, 22nd and 23rd). Singer ran as the two-term alderman of the 43rd Ward and leader of the city's independents. His leadership was symbolized by his role in the 1972 Democratic National Convention, where Singer and Jesse Jackson led the independent Democratic delegation in unseating the Daley-led regular Democratic delegation. Singer's mayoral votes reveal the validity of the "lake-front liberal" cliche since seven of his nine best wards were the 5th (Hyde Park) and the six wards which front on the lake from the Chicago River to Evanston (42nd, 43rd, 44th, 46th, 48th and 49th). Singer also demonstrated some appeal to black voters, surpassing 30 per cent in nine predominantly black wards. He also scored over 30 per cent in six off-the-lake northside wards. Thus, his total "north of North Avenue" was over 30 per cent in 11 of 17 wards versus over 30 per cent in only 11 of 33 wards south of North Avenue. These totals again demonstrate the comparative weakness of the Democratic organization in relatively affluent, white, north-side areas. Not surpisingly, the two black state senators who ran for mayor did reasonably well in black wards but got very little support elsewhere. Neither was portrayed in the press as having a chance to win, and neither had sufficient finances or workers to launch a credible citywide campaign. Washington, running in 1977 against Bilandic, did much better than Newhouse who ran against Daley in 1975. Newhouse had to divide black votes with the liberal Singer and failed to carry a single ward; he made his best showing in the 6th and 21st where he received 23 per cent of the vote. Washington carried five wards and more than 23 per cent of the votes in 16 wards. His best showings came in the black middle-class wards (6th, 8th, 9th, 17th, 21st and 34th), where he scored |

|

much better than in inner-city south and west side black wards. On the other hand, Newhouse scored at least 2 per cent of the vote in every ward and got 376 votes in his lowest ward total. Washington was below 376 votes in 17 wards and below 2 per cent in 16. In short, Washington's vote was much more concentrated in the black community than was Newhouse's support. In comparing the 1975 victory of Mayor Daley with the 1977 triumph of Mayor Bilandic, the most obvious difference lies in the turnout for the winners. Daley ran almost 100,000 votes stronger than Bilandic 463,623 to 368,400. The total vote count for their combined opposition was nearly the same in both years. While Daley received over 60 percent in 21 wards, Bilandic could only match that total in 10 wards. The 10 committeemen who produced for both were D'Arco (1st), Vrdolyak (10th), Daley (11th), Madigan (13th), Burke (14th), Hynes (19th), Marzullo (25th), Quigley (27th), Rostenkowski (32nd) and Kelly (47th). These primary elections bear out the "second-choice phenomenon" of Chicago politics. Simply stated, some Chicagoans will vote their own ethnic preference ahead of the endorsed Democratic candidate, but without a candidate of |

|

February 1979/Illinois Issues/19

their own ethnic background, Chica-goans will vote for the regular Democratic candidate. This makes it virtually impossible to put together a coalition against the Democratic party candidate. For example, Pucinski, Washington, Hanrahan, Willa Mae Reid and Anthony Martin-Trigona totaled 352,483 (49%) against Bilandic's 368,400 (51%) in 1977, but if there had been fewer candidates in the race, it would have been Bilandic who benefited rather than his opponents.

1979 election forecast

The 1979 city council elections find the Republican party in its weakest position since the advent of the 50-ward system in 1923. Back in 1923 and 1927, the Republicans elected 19 aldermen, a total they have not since matched. After falling to only nine aldermen in the midst of the Depression, the Republicans regained strength and won 17 council seats in 1947 and 16 in 1951. Their decline since then has been continual. In the 1975 aldermanic elections only one Republican was elected Dennis Block of the 48th Ward. Block subsequently ran for mayor against Bilandic in 1977 and lost every ward in the city. He then resigned his aldermanic post and moved to the suburbs, as most Republican voters had done long ago. An independent, Helen Volini, was elected at the special aldermanic election to replace Block, thus leaving the Republicans totally without representation on the city council.

Last year, the Republican party discussed supporting independent candidates in some wards rather than fielding their own nominees. With the last two strong Republican wards in the city now firmly in the hands of Democrats Pucinski (41 st) and Kelly (47th), it is unlikely that Republicans can elect anyone in 1979.

Chicago's independents also face 1979 with uphill battles. The victorious candidates of the heady days of the late sixties and early seventies, when independents were on the march, have all been defeated or have retired. Ross Lathrop (5 th), Martin Oberman (43 rd) and Volini (48th) are the only incumbent independents who will be seeking reelection. Other fairly serious independent challenges will come in the following wards: 3rd (Ralph Metcalfe, Jr.), 29th (Cliff White), 44th (to replace Simpson), 45th (Mike Holewinski) and 49th (David Orr).

The only other possible irritation to regular Democrats will come where contending factions battle for control of the ward. These disputes are not infrequent; for example, in 1975 they occurred in the 19th and 33rd wards. This time contests within the ranks of the regulars include the 7th, where Joseph Bertrand, former regular Democratic city treasurer and present ward committeeman, is challenging incumbent Wilin-ski; the 24th, where David Rhodes, the incumbent who was not slated this time by the regulars, against the slated candidate, Committeeman Shumpert; and the 35th, where Marcin, longtime city clerk was not slated for clerkship this year, against the current alderman and vice-mayor, Casimir Laskowski. Two other incumbents who were not slated but are running are Solomon Gutstein in the 40th against slated candidate Ivan Rittenberg, a Chicago policeman, and in the 49th, Esther Saperstein is running against the regular candidate Homer Johnson. In sum, the outcome of the 1979 council elections will likely be very similar to that of the last election in 1975 when 143 candidates were on the ballot and 117 of them gathered 1,000 votes or more. Ten aldermen (all regular Democrats) ran unopposed, therefore, the Chicago electorate living in 40 of the 50 wards were able to choose among 133 candidates, of whom 107 were regarded as serious enough to award at least 1,000 votes each.

The 1979 city council elections find the Republican party

|

The wide range of choices did not dissuade most voters from supporting regular candidates, of whom 40 received over 50 per cent of the vote in February and were elected. In addition to the 10 who were unopposed, 19 other regulars received over 60 per cent of the vote. Two independents, Bill Cousins and Dick Simpson, also won in February. In the eight April runoffs, regulars won five, including Wilinski (7th) and Joyce (19th), who won factionalized fights among the regulars, along with Shan-non (17th), Laskowski (35th) and Ray-mond Fifielski(45th); independents won two Lathrop (5th) and Oberman (43rd); and Republicans one Block (48th). The result was a city council with 45 regular Democrats, 4 independents and 1 Republican.

Mayor Bilandic, at this writing, appears to be an absolute certainty for both the Democratic nomination and reelection in April. The likely Republic-can nominee, Wallace Johnson, should be an odds-on favorite to extend his party's futility record of failing to carry a single ward as in the 1975 and l977 mayoral elections. If Bilandic has little to worry about from the Republicans, he has even less to be concerned about from challenges inside the party. His only opponent of note is former city Consumer Commis-sioner Byrne, who lacks any base of suppport within the party or among the voters. Byrne's campaign apparently peaked 18 months before the election with the "taxigate" press coverage which brought her name before the public in opposition to Mayor Bilandic.

The fact that Bilandic is virtually without opposition is attributable to at least three factors: his behind-the-scenes work uniting party-business-labor inter-ests to support him as Mayor Daley's successor, public satisfaction with his policies, and his personal popularity. In the days following Mayor Daley's death two years ago, few would have predicted Bilandic's current dominance of Chicago. The fact is that Bilandic is unbeatable in 1979, and the Democratic party continues to carry on in the tradition of Cermak and Daley. Cer-mak's legacy was the consolidation of the Democratic party under one leader. Because of his strong command for more than two decades, Daley went further than Cermak and consolidated the party and the city. Bilandic's goal is to maintain the consolidations, but he can probably never attain the dual party-city leadership enjoyed by Cer-mak and Daley unless he becomes a ward committeeman. At present, he lives in the 11th Ward where the late Mayor Daley's son, state Sen. Richard M. Daley, is committeeman.

February 1979/Illinois Issues/20

|

|