By ROBERT McCLORY

IT WAS 6:30 p.m., February 27, 1979. The polls in Chicago had just closed, and radio reporters were trying to fill the gap until the first election results would start coming in. Someone spotted George W. Dunne, the chairman of the Cook County Democratic organization, and shoved a microphone in his direction. Was he worried? Did he think the predicted anti-Bilandic movement would hurt much? Did the unusually heavy voter turnout foreshadow ill tidings?

"No," said Dunne, in his usual calm, polite style. There was no way the Democratic organization could blow this one. But what if, the reporter persisted, what if, by some miracle, Jane Byrne should win? Did Dunne have a contingency plan? Was the party prepared to deal with such an upset? The chairman almost chuckled. "No," he said again. There was no plan because there was simply no way that could happen. "We haven't discussed it," he said. "We're confident."

Three hours Tater, Dunne knew how wrong he was. Mayor Michael A. Bilandic had blown it. The party had blown it. He had blown it. Jane Byrne was carrying precinct after precinct — even in many old bastions of party loyalty. The feisty little woman was coasting to an easy victory, not so much on her own merits but on an incredible combination of poor judgment, arrogant presumptions and acts of God. Whatever the reasons, the people's choice for mayor on the Democratic ticket was Jane Byrne.

Nobody knew what it meant. Party veterans feared it was the end. Ward Committeeman Edward A. Quigley said he didn't need any Jane Byrne. Aldermen like Edward M. Burke and Edward R. Vrdolyak fled the cameras and microphones. And Roman C. Pucin-ski's fertile brain was casting about for a way out — possibly by placing a more controllable organization candidate on the ballot in the general election under the Socialist Worker banner!

It was panic time. Mayor Richard J. Daley's old machine had sustained a serious, maybe fatal blow. There was no contingency plan — only a jubilant Jane Byrne, a surprised citizenry, and a disorganized organization. But there was also a George Dunne.

Only two weeks before this upset, I had talked at length with him about his approach to politics and government. One thing had been made clear to me: Dunne does not panic. He is oriented toward finding solutions, building bridges.

After Byrne's win

The day after the election, the chairman was at the microphone again. calmly sharing his expert assessment: "This [upset] indicates that democracy in Chicago is alive and well. The voters told us something. We'd better be responsive to the issues. It was an accumulation of aggravations that brought this about." During the following week, Dunne oversaw a series of closed meetings between the ward committeemen and Byrne. At first, relations between the candidate and the troops were terribly

April 1979/Illinois Issues/18

strained. But Dunne's smile was a little broader each day as he emerged from the discussions — invariably at Jane Byrne's right hand. The emerging message was that she would not dismantle the machine, only streamline it. And the party leaders, in return, would give her full backing in the April general election. Byrne, in fact, agreed to give Dunne final word on City Hall patronage appointments. Under Bilandic, these jobs had been doled out through the mayor's office. Under her administration, it would be different, said Byrne: "Dunne is the chairman, and he should have his say in the patronage system." Quigley called her "wonderful," Vrdolyak and Burke were smiling again, and Pucinski lost all interest in socialism. The man who made the difference was George Dunne.

George Dunne is a different kind of politician. After nine years as president of the Cook County Board and two years as Mayor Richard Daley's successor as chairman of the Democratic organization, Dunne doesn't have a press representative and he still personally talks at length to almost anybody. It is the kind of honest, open, let-it-all-hang-out approach that has gotten other politicians in trouble. Too much candor can sour the atmosphere. With Dunne, it works — partly because he himself has a built-in screening device that filters excessive candor better than anything a hired hand could do, and partly because with George Dunne a lot of filtering isn't necessary. For the most part, what you see is what you get.

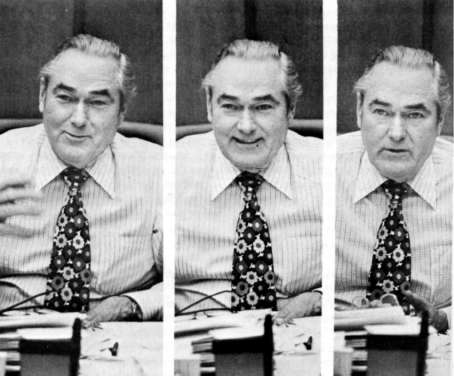

Dunne is a tall, husky, handsome man of 66 who talks with a "Chicagah" accent and who looks a little like John Connally, the Texas Democrat turned Republican. In Dunne's career there have been no turns. It has been so straight and so consistent for the past 30 years that it looks prepackaged.

He grew up on the Near North Side of Chicago in the shadow of Holy Name Cathedral (where his father was the sexton), attended De La Salle High School and Northwestern University (studying sociology, psychology and education but dropping out before graduation), then worked 29 years for the Chicago Park District, slowly moving up from playground supervisor to assistant general superintendent. He was in the army for three and one half years during World War II, seeing action on Saipan and Guam. He then

returned to active duty for almost two more years in the Korean War and continued after that in the Illinois Air National Guard for many years.

He was a precinct captain in his home ward (the 42nd) at 18 and has been the bulwark of the local organization since. Between 1955 and 1962 he served four terms as a representative in the Illinois General Assembly, winding up as the majority leader in his final term. Dunne was then appointed and subsequently elected a member of the county board, serving as chairman of its finance committee until he was elected president by the other commissioners in 1969 to succeed Richard B. Ogilvie. In three general elections since, he has won with ease. Following Daley's death, Dunne was chosen chairman of the Cook County Central Democratic Committee, and he won a unanimous vote for reelection last fall.

He has three children (now grown and on their own) and four grandchildren and still lives with his wife, Agnes, in the old neighborhood where he was raised (which includes the Gold Coast, housing some of Chicago's richest, and the Cabrini-Green project, housing its poorest).

Dunne's steady climb

Obviously then, Dunne's rise up the ladder has been remarkably steady, but not meteoric. It has happened so slowly, in fact, that Dunne is often taken for granted by the citizens of Cook County. There have been no scandals connected with his career and few memorable controversies. Consistently Dunne comes across on the people's side, as he definitely has in the recent flap over the 30 per cent salary hike the commissioners voted themselves. When he was first sworn in as county board president, the Chicago Tribune called him a "respected and financially astute administrator." Ten years later, he was still fostering that same image. The campaign slogan in 1978: "Dunne works."

Dunne has to work. He and the 15 other members of the county board (10 elected at large from Chicago and 6 from the suburbs) are administering this year a $220 million budget, with 75 per cent of it going to finance the county's mammoth criminal justice system: the courts, the jails, and the offices of the sheriff, state's attorney and medical examiner. The board has direct respon-

sibility for the county's unincorporated areas (about 180 square miles), plus highways and bridges, forest preserves, job training programs and health centers. Its overall realm numbers 5.5 million people (a population larger than that of 40 states), and it includes Chicago and 128 other municipalities, 30 townships, 640 separate taxing districts and 10,000 employees.

It costs the public to support all this — 1 cent on every gallon of gas, $1 on every gallon of hard liquor, and $15 on every car purchase, for example. But few citizens complain loudly about county taxes. George Dunne has such an honest, earnest face, and the other commissioners have traditionally been such a benign, innocuous group.

Then there is Dunne's role as chairman of the party. The predicted split among would-be leaders did not occur following Daley's death. Dunne kept the 50 ward committeemen from the city and the 30 township committeemen from the suburbs, plus the 5,000 precinct captains and their assistants marching in lock step, even though his method of settling disputes was more low-keyed; more open-ended than Daley's.

Then, out of the blue, came Jane Byrne and the snow. Suddenly, in one day the whole organization fell apart — so completely that the experts, in retrospect, are inclined to see it as more of an anomaly than a sign of permanent collapse; it's "an accumulation of

April 1979/Illinois Issues/19

aggravations," insists Dunne, not a rejection of the Democratic organization. In the moment of chaos Dunne had to step into the limelight and put things back in order. He does not like a lot of public attention, preferring to operate quietly behind the scenes.

That is a basic reason why Dunne gets so little feature coverage in Chicago. He was awarded only a passing mention in the best selling books about the Daley years by columnist Mike Royko and commentator Len O'Connor. He doesn't get into the gossip columns at all, and one looks in vain for any magazine articles about the man, despite his long career and his two high pressure positions. When his views and reactions on specific issues are reported, they are almost always presented in a favorable light, even by the gritty newsmen who delighted in baiting Mayor Daley. George Dunne is not easily baited — or hooked.

City Hall

On the fifth floor of the County Building in downtown Chicago are the huge glass doors that open to the office of George Dunne, president of the board. At the other end of the long hall are identical doors which lead to the office of the mayor of Chicago. The casual visitor doesn't notice it, but the two offices are actually in separate buildings which have been ingeniously wedded together. When City Hall and

the County Building were originally constructed side by side, they were divided by a thick brick wall. Over the years, the two governments and their politics became so entagled that it was decided to tear down the wall and let everyone function as one happy family. That was the way it was with Daley and Dunne for eight years. That was the way it was with Dunne and Bilandic. Apparently, that's the way it will be with Dunne and Byrne.

When I sought an interview with Dunne, I had no trouble getting an appointment. He put no limits on subject matter or time. "I'm always anxious to help the press," he said in a husky voice somewhat reminiscent of the late Mayor Daley. Indeed, during our conversation for the next two hours I was constantly reminded of Daley: the familiar platitudes, the homey sayings, the incredible oversimplifications, the occasional injections of humor, the flashes of originality. At times I wasn't sure whether he was pulling my leg or really speaking from the heart. But unlike Daley, there were no outbursts of indignation, no self-righteous posturing, no mangling of the language. Dunne is by no means as bland as Bilandic, but he is far less colorful and quotable than Chairman Daley.

On the crucial issue of shrinking population in the county, Dunne frankly admitted he had "no panacea." Between 1970 and 1975 the six-county area around Chicago lost 283,000 persons. The city alone lost 8 percent of its population and similar losses were reported by close-in Cook County suburbs like Cicero, Berwyn and Evan-ston. The people loss, said Dunne, is intimately related to the job loss, "and we just don't have any solution for that yet."

Last year, the county board, at Dunne's recommendation, adopted a tax incentive ordinance which allows assessments at 16 per cent of value for the first five years on new commercial or industrial developments moving in from outside the county (the normal assessment is 40 per cent). Although no one has yet used the plan, Dunne said, "I'm not too worried about population shifts. Sure, we've lost some big operations like the Donnelly and Berlin plants to the Sun Belt states. But in other areas, like the service trades, we seem to be now getting an increase in the county." With the cooperation of the utility com-

panies, chambers of commerce and local governments, said Dunne, "we'll see it through. We should all pray for better weather, too."

Dunne likewise had no special solution for the critical exodus of whites from Chicago although he expressed more urgent concern on this point. "It's absolutely necessary to maintainan integrated city," he said. "It's necessary for survival. Business, labor, banking — they've all got to unite to stop the flight."'

Despite the significant increase in the black population, Dunne conceded there has been no solid increase in black participation in government or politics. "The voter turnout [in black areas] is bad," he noted. "There's just terrible apathy. Such a great resource — but we're not able to tap it and we're sure not getting any answers from our black leaders."

Black voters

The great outpouring of black voters in the mayoral primary has not convinced Dunne or other party leaders that the days of apathy are over. Tht black vote (which, by itself, gave Byrne most of her victory margin) was it reponse to aggravation, he believes, especially the blatant aggravation created by cutting all rush hour elevated train service to the most populous black areas of the South and West sides, in the midst of the winter snow-in. Just as black voters in 1972 rose in unified anger against State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan, so they vented their collec-tive rage in 1979 against the Bilandic administration. Dunne does notsee occasional protests or unpredictable crises as effective foundations fora political organization.

Dunne reminisced about the early, 1960s, when as ward committeeman, he proudly dedicated a new indoor-outdoor swimming pool in the trouble-plagued Cabrini-Green housing project. "I talked to the people about what great utility it could have, about it helping the youngsters learn life saving. I thought they could even have water ballets. Later when I visited Cabrini, there wasn't anybody in the pool. It wasn't being used. I went to the park district gym, and there were a few guys standing around in there in street clothes. It's like that in politics. Blacks don't participate I don't know what it is . . . ."

The suggestion that the apathy is the

April 1979/Illinois Issues/20

product of years of exclusion from the political system drew a nod of agreement from Dunne. "Yeah, I know," he said. "They're not in the mainstream." But, he added, getting minorities into the mainstream is a difficult task even for the chairman of the Democratic party, thanks to the Shakman decision and similar court rulings which have weakened the patronage job system. In essence, argued Dunne, the political jobs held by the oldtimers (mostly white) cannot be stripped from them arbitrarily and given to deserving blacks or other minorities: the liberal assault on the machine has backfired.

These obstacles notwithstanding, Dunne insisted the patronage system as practiced in the city and county is alive and well. "In the past — 10 years or so ago — patronage was tarnished by some unscrupulous political leaders. There may have been shakedowns and payoffs and the like. But now that's as much past history as home brew. Anything going on today is miniscule."

Under the agreement with Byrne, Dunne will have a lot more to say about patronage than in the past. It was essentially her resentment of the old boy control of City Hall patronage jobs by Bilandic's Southwest Side cronies which prompted her to shift the control to Dunne, one of the few men she trusts in her strange new environment.

Regular revelations of political scandal by writers like Royko of the Chicago Sun-Times do not alarm Dunne. "What you must realize is that Royko is a humorist, and the essence of humor is exaggeration. I enjoy his stuff myself. But he exploits things way beyond their limits." Even the lengthy Mirage Tavern expose'of graft and corruption reported last year by the Sun-Times did not disturb Dunne. "They made more of that than was there," he said. "They had pictures of people accepting envelopes, but that's no proof the public employees knew what was in them."

Patronage and Daley

Patronage, said Dunne, permits officials like himself to weigh job recommendations from a variety of leaders in business, labor, religion or politics and then make their own informed choice. "And I'm jealous of my own reputation," he added. "I'm always gonna pick the top, the best qualified guy." Daley never condoned

corruption or dishonesty, emphasized Dunne. "For example, he always called in anyone with excessive drkinking or extra-marital troubles, and if they didn't reform, he kicked them out of politics." Asked if this applied equally to those accepting money under the table, Dunne replied, "Oh, yeah, sure. That too."

Dunne said he always held Daley in "the highest esteem as a teacher, legislator and administrator," but his association with the late mayor was "political, not personal," and he has never been inside the Daley home on the South Side.

Dunne's aggressiveness

His mild, unassuming manner notwithstanding, Dunne can occasionally lash out with telling effect. When he does lower the boom, it is a deliberate move well calculated to make a point and not to alienate permanently or set off some political vendetta. Even President Jimmy Carter felt the lash last year when he failed to respond to Dunne's repeated invitations to attend a major Democratic dinner in Chicago. Dunne finally let it be known that since the President was so busy, he had been "disinvited," and the invitation was being offered instead to California Gov. Jerry Brown. Almost miraculously, Mr. Carter's schedule suddenly opened up and he apologetically agreed to come to the affair. Fortunately, said Dunne, Brown couldn't come "or we might have had both of them here."

Dunne was equally on target in 1970 when Republican Joe Woods (brother of Rosemary Woods, of 18-minute-gap Watergate fame) mounted a major campaign to unseat him for the board presidency. With heavy financial backing from millionaire W. Clement Stone, Woods was omnipresent on television and radio belaboring Dunne for the shameful number of abandoned automobiles desecrating Cook County. The blitz fizzled, however, when Dunne publicly produced the appropriate statutes showing that responsibility for hauling off the cars was on the shoulders of the county sheriff, not the president of the board. And the sheriff at that time was one Joe Woods.

Woods was back as his opponent in the 1978 election, but his support was anemic this time, and Dunne slaughtered him at the polls as expected.

"We should never underestimate an opponent," said Dunne. "We must always assume he is strong." That is a lesson, he agrees, which can be occasionally forgotten even by old pros like himself.

Last November, Dunne was mightily embarrassed when the Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate, Alex R. Seith, blew an apparently commanding lead during the last two weeks of the campaign and eventually succumbed to incumbent Sen. Charles H. Percy. In a decidedly uncharacteristic display of sour grapes, Dunne accused Percy of faking his highly publicized fainting spell while preparing for a television debate.

More typical of Dunne's fighting style is his aggressive stance with the county board members over the salary increase they awarded and reawarded themselves. Like a tough schoolmaster repeatedly reprimanding a class of greedy children for stuffing themselves with sweets, Dunne has fought the hike as "outrageous and unjustified" from the start. At the same time he has been careful not to attack the members individually or impute their motives. The commissioners are "hard working, responsible, honest and dedicated," he has insisted, but they are not entitled to 30 per cent hikes (from $25,000-a-year to $32,500), not when hourly employees of the county are getting a 4.5 per cent raise. He vowed to oppose their efforts "through the courts or any other way

April 1979/Illinois Issues/21

that is legal," and he thereby gained broad editorial applause in the local media. The issue conceivably could trigger a permanent break between the president and the board members, but on the basis of Dunne's past performance, this quarrel will probably be settled quietly behind closed doors and the general public will never know exactly how.

The salary dispute has convinced Dunne the commissioners should be elected from specific geographic zones in the city and the suburban areas instead of as at-large members. That proposal has been discussed for years but never acted upon. Dunne formerly showed only guarded support for it. Now he says he will back it without qualification because "it would make the commissioners more accountable to a definite constituency."

'Being of service'

Dunne said he doesn't see his twojobs as totally separate responsibilities, but as "running parallel," and he instantly launched into a favorite theme: "You see, being of service gets into your nature. Government is our most priceless impersonal possession. We are recorded into this w'orld by some governmental entity and we are recorded out. In between, everything we do has some governmental aspect. And all of this is entrusted into the hands of those who are elected. They are the temporary custodians. When they are

through, the governmental entity should be returned in better condition than when they took over . . . ." It sounded corny, but there was little doubt Dunne sincerely meant what he said.

Usually, he walks to work from his apartment on Chestnut St. (where he and his wife have lived for 26 years). When the weather is bad he rides the subway, but he never takes a limousine. Many weekends, he and Agnes drive to their 80-acre farm in Hebron, 90 miles from Chicago, where he putters around the garden and raises lettuce and tomatoes.

But he considers himself essentially a "workaholic" and said he gets his major satisfaction from "being of service." He holds open meetings of the county board twice a month at which any citizen can address the members on any subject. "And we listen. It was at one metting that a lady named Mary Powers [from the Alliance to End Repression] first introduced the medical examiner concept [in place of the coroner system], and we liked the idea, pursued it, and in 1976 it was introduced here."

As chairman of the party, he also holds open meetings at the Bismark Hotel headquarters, and at this level too he is considered amenable to suggestions and innovation, certainly more so than Daley. By Dunne's order, the organization for the first time in its history is now issuing quarterly financial statements.

Clearly, Dunne's passion for "being of service" influences almost everything he does, from handling his own public relations ("the taxpayers are paying for me, not for some PR man") to breaking through the red tape of county government to get someone a job, an apartment or emergency food ("that's where the inner satisfaction comes from"). George Dunne lives in an extremely rational world, where emotions are controlled, motives are clear and problems are solvable. It's where he has lived throughout his career.

It seems so simple you can't help wonder how he handles all the crises, tradeoffs, deals and manipulations that are part of the confusion of political life. Indeed, he not only handles it, now he reigns over it. In him, a combination of innocence and shrewdness, idealism and realism, of openness and secrecy, balances out just right.

Somehow, George Dunne works.

April 1979/Illinois Issues/22