|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Redlining: A black and white issue? By John N. Collins |

|

Discrimination against minority and racially mixed neighborhoods in making home mortgage and improvement loans is both illegal and hard to prove. But documentation alone won't solve the urban crunch. |

|

[Obtaining credit to purhcase or repair a home in urban neighborhoods is just one of the problems faced by Americans in their search for a decent place to live. We plan to examine other facets of the housing problem in future issues. --Eds.] |

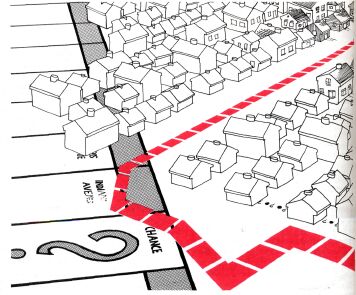

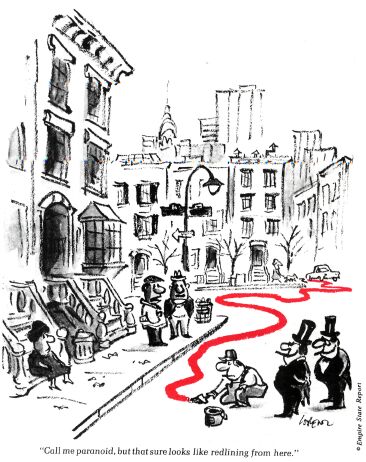

REDLINING, a tactic with a longer history than its discovery in the 1970's would suggest, evokes emotional charges and denials about who is responsible for urban decay. The term originated from a mortgage lenders' practice of circling on a map whole areas, often zip code areas, with a red line. These redlined areas were then designated as off limits for receiving home mortgage or improvement loans. To some, the lines meant financial prudence. To others, they meant racism and other forms of bigotry. In either case, the effects were like the red line on an airplane's instrument panel: they spelled a nose dive, a potential disaster for the people involved.

Separating fact from fiction and unraveling the underlying causes and consequences of redlining is still a major public issue in Illinois. The lofty goal enunciated by Congress in 1949 of a "decent home and suitable living environment for every American family" still eludes many Illinois residents as well as other Americans. The issues surrounding redlining lie at the heart of the problem of providing adequate housing for urban America.

The circling of neighborhoods with a red pen is no longer done, but the underlying process of an urban credit crunch continues. Whether this is caused by unfair, unjustified, discriminatory denial of financing to whole neighborhoods, as the term redlining indicates, or by objective, financially prudent directing of financing away from older urban areas, the consequences for neighborhoods are equally devastating.

Neighborhood decay

The availability of institutional financing for home purchase or improvement is the lifeblood of a healthy neighborhood. Owners may be unwilling to maintain or improve their properties if they cannot expect to redeem their investments through future resale or remortgaging. The result is decay and deterioration in those areas. Even those owners willing to forego redemption of their investments may be unable to maintain their homes in good repair when home improvement financing is not available. Owners wanting to leavea neighborhood but unable to sell their homes will resort to converting them to rental properties, with no incentive to invest any more funds in home maintenance.

The drying up of the normal housing market makes an area prone to panic sales, often accelerated by the blockbusting tactics of unscrupulous real estate agents. Speculators can then move in, buy cheaply and milk the property as rental housing. The home buyers who are then steered to the area by real estate and lending institutions are often poorer minorities who are inexperienced as homeowners and who can't afford home improvements, much less know how to complete them. All too often, when neighborhoods change like this there is a reduction in traditional public services such as police and fire protection, street and sidewalk maintenance, sanitation, public health monitoring and cleanup. Bad situations get steadily worse, and urban blight proceeds unchecked.

Sales, resales and refinancing transactions are essential to a sound housing

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 04

market and a healthy neighborhood; but when credit is not available, this kind of activity is stifled. When reasonable interest rates and repayment periods and moderate down payments are not available in an area, stagnation sets in as owners lose incentives and opportunities to maintain their properties.

An alternative to conventional financing (traditionally from community-based savings and loan institutions) is the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) or the Veterans Administration (VA), which both offer insured loans. Until 1968 these insured loans were instrumental in opening up the newer suburbs to young families who lacked the savings to make a conventional down payment. After 1968 FHA regulations changed to allow homes to be certified for FHA insurance without reference to the condition of the surrounding neighborhood. This opened up older, partly run-down urban neighborhoods to FHA-backed loans, resulting in a strong upsurge after 1968 in urban-insured loans by FHA.

The legacy of that policy is the "FHA'ed" neighborhood. Lending in these areas becomes dominated by mortgage bankers rather than savings and loan institutions. Mortgage corporations, operating with little investment capital of their own, routinely sell the FHA-backed mortgage to secondary market investors, in particular the Federal National Mortgage Association, nicknamed "Fannie Mae." With little direct stake in the continuing viability of the loan, these corporations can often short-circuit the basics of sound mortgage lending practices. Property can be overappraised, and the basic structural deficiencies of homes ignored. Purchasers with weak credit ratings and low incomes can be sold homes beyond their incomes, even if there are no unusual home maintenance or repair costs.

Such loans are then serviced by the mortgage bankers, who realize their main profit from the loan through immediate, up-front charges, and then sell the mortgage to a secondary investor. Little or no effort is made by the now disinterested mortgage banker to assist the struggling new homeowner with the financial skills needed to remain solvent. Finally, a single instance of late payment can be used as an excuse to initiate foreclosure, avoiding the forebearance guidelines set forth by FHA. The result is abandoned homes awaiting the lengthy process of becoming eligible for resale, and subject in the meanwhile to rapid deterioration from vandals and lack of maintenance. In sum, the insured mortgage alternative to conventional institutional mortgage financing has, in many areas, been disastrous.

Conventional loans

Given the importance of conventional mortgage financing in maintaining and improving neighborhoods, the charge that conventional lenders have engaged in redlining by rejecting home purchase and improvement loans in vulnerable urban areas is a serious one. Mortgage disclosure data (required by the 1976 Federal Mortgage Disclosure Act) was reported in a 1978 study by the Chicago-based National Training and Information Center. This report confirmed expectations that most conventional mortgage money was flowing into solid, middle-class suburban areas. Relatively little was invested in older, racially mixed, lower income areas. One-half of all the census tract areas in the Chicago Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA), mostly in the second ring of suburbs, received 87 percent of all conventional residential mortgages, leaving little mortgage money for the city of Chicago.

Although they admit to low levels of mortgage lending in older and poorer urban areas, the representatives of financial institutions claim that they have been unjustly maligned. Lenders say that low levels of conventional lending simply reflect the fact that there is less demand for such lending in many urban areas. Furthermore, they assert that the risks in those areas are too high for the home purchase or improvement loans which would insure a good rate of return for their depositors. Sound lending and investment practices, they argue, cause a lower rate of investment in urban areas.

Despite this argument, however, denying mortgage money to whole geographical areas seems arbitrary. Such denial ignores the real variations in individual home conditions and individual commitment and financial capacity to maintain a home investment. Red lines may not be found on maps any more, to be sure, but they seem to be alive and well in the minds of a good many lenders.

Numerous studies have shown that racially mixed or minority segregated areas receive far fewer conventional mortgage loans than predominantly white areas. Conversely, the ratio of conventional loans to insured loans decreases sharply for neighborhoods with more minority populations. The percent of minority population in a neighborhood has been acknowledged by conventional lenders to be a negative factor in granting loans. A 1972 study by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development of lending practices showed approximately 20 percent of lenders were using racially based criteria as negative factors in granting loans. A 1971 Federal Home Loan Bank Board survey showed that 30 percent of the surveyed savings and loan institutions disqualified neighborhoods with low-income or minority populations.

Although such racial considerations are now illegal, the racial characteristics of loan applicants and of neighborhood are so intertwined with other characteristics such as income, age of home, price of home, credit record, etc., that it is impossible to say that race is the sole

July 1979 / Ilinois Issues / 05

reason mortgage applications are turned down. At the federal level, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, the regulatory agency for federally chartered savings and loan institutions, has recently issued regulations which state that "refusal to lend in a particular area solely because of the age of the homes or the income level in a neighborhood may be discriminatory in effect since minority group persons are more likely to purchase used housing and to live in low-income neighborhoods. The racial composition of the neighborhood where the loan is to be made is always an improper underwriting consideration."

This regulation is consistent with a 1976 Ohio District Court decision which held that a prospective home buyer denied a loan because of neighborhood racial composition can bring action under Title VIII of the 1968 Civil Rights Act. In Illinois, the 1974 Savings and Loan Act prohibits racial discrimination in lending practices of regulated savings and loan institutions. The Illinois Fairness in Lending Act of 1975 prohibits financial institutions from denying or varying terms of a loan on the basis of geographical location of the property, or using lending standards that have no economic basis.

But the redlining issue cannot be easily distilled down to a legal-illegal, black-white dichotomy. Lending decisions are extremely complex and require a lot more information than we now have before systematic discrimination can be proven. The major effort during the past six years by community organizations concerned about redlining has been to obtain mortgage disclosure laws such as the Illinois Financial Disclosure Act, which was passed in 1975. It required banks, credit unions, savings and loans, insurance companies, and mortgage banking companies to file semiannual statements of deposits and various types of mortgage loans and applications. Information was to be reported by census tract and zip code area for conventional and insured residential mortgage loans, home improvement loans and construction loans in counties over 100,000 in population. But the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in January 1977 that federally chartered banks don't have to comply with the state law, and, in May 1978, ruled the entire act unconstitutional.

Spurred by the leadership of Gail Cincotta, executive director of the Chicago-based National Training and Information Center (NTIC), community groups pushed through Congress the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975. Although still limited as a means of collecting enough solid information about lending practices to nail down the redlining hypothesis, the act is quite important. It makes explicit the obliga tions of savings and loan institutions to their local communities. Congress states in the preamble to the act that it "finds that some depository institutions have sometimes contributed to the decline of certain geographical areas by their failure pursuant to their chartering responsibilities to provide adequate home financing to qualified applicants on reasonable terms and conditions."

Intended as a monitoring tool, the act's goal is to provide enough information to local groups and residents to determine whether depository institutions are fulfilling their obligations to serve their local communities' housing needs. The act requires regulated depositories, thus excluding mortgage bankers, to keep available at their main office a report, by year, of the number of approved residential mortgage loans, broken down by size of units, and the total dollar amounts of such loans. Since 1977 this information has been collected by census tract.

Because of the way this information is collected and filed, thorough analyses of lending patterns in various areas from all sources is quite difficult to obtain. The best analysis so far is contained in the 1978 report by the National Training and Information Center cited earlier. Using community organizations in eight metropolitan areas, NTIC was able to show that "large areas of all central cities get very few or no conventional mortgages, and the bulk of conventional mortgage lending is concentrated in a few parts of each metropolitan area." The report concludes, however, that "the data available under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) is insufficient to conclusively prove practices of intentional, arbitrary geographic discrimination in real estate lending. Rigorous scientific or legal proof would require more and better data than HMDA forces lenders to disclose."

Insured loans

One especially interesting finding from the NTIC study is that the areas highest in home improvement lending were also the areas with the lowest conventional mortgage lending. This was particularly true in the Chicago metropolitan area. However, because the data required by HMDA lumps together federally insured and conventional home improvement loans, it is likely that the high incidence of home improvement lending in areas with little conventional lending is due to heavy reliance upon federally insured home improvement loans. In short, the same pattern that exists for home mortgages -- where conventional loans are directed to middle-income areas while government insured loans go to older, low-income urban areas -- also operates for home improvement lending. Insured loans reduce the incentive of lenders to make loans which are likely to be viable for the homeowner and for the neighborhood.

To provide the critical mass of facts needed to understand the patterns and causes of the urban credit crunch will require much more disclosure than the current laws demand. Meaningful disclosure requires, in addition to loan volume and location, information on the social and economic characteristics of both successful and unsuccessful applicants, and information on the

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 06

condition of the property. NTIC includes in their list of suggested disclosure requirements the need for information on lending patterns by mortgage bankers, as well as savings and loans, and of deposit data by census tract rather than by office location to determine if the lofty principles of community responsibility by depositories are being met. These views were also echoed by the recently issued President's Neighborhood Commission Report, noting that HMDA is the sole reinvestment monitoring tool available and needs to be strengthened and made permanent.

|

Unfortunately, disclosure data collected so far still does not address the two major contentions made by lenders to show that nothing more than prudent lending practices have determined whether loans are given. Both points have weaknesses, but they illustrate the complexity of the issue and the difficulty or getting solid proof to explain the urban fiscal crunch. On the one hand, lenders claim they meet all the valid demand for loans, and that the decreased volume of lending simply reflects lower credit needs and/or capacity of residents in older, low-income areas. In addition, and closely related to the issue of demand, there is the argument that lending in older or transitional urban areas is risky. The argument that there is limited demand for loans is hard to support or refute with the available data. Disclosure laws like the ill-fated one in Illinois, requesting disclosure of loan applications, are still so fraught with limitations as to be misleading. Loan applicants usually believe, or at least hope, they will get their loans, and they have higher hopes, of course, in healthier neighborhoods. But the effort to make written application can be blunted by a discouraging conversation with a bank employee or even by others with experience at the bank. Simple observations of the vigorous lending activity of insured loans (FHA- or VA-supported) in areas receiving little conventional financing indicates that there is a demand for home purchase and improvement loans. The experiences of the Neighborhood Housing Services Projects in Chicago and elsewhere show clearly that credit worthy applicants in declining areas can be encouraged by receptive lenders and aggressive marketing strategies by community groups. Demand is not something fixed in concrete; it is responsive to the efforts of lenders to encourage or discourage lending. Self-fulfilling prophecies |

|

But underlying the reluctance of lenders to positively encourage home loans is the second factor: the perceived lending risk in many urban neighborhoods -- which encourages redlining. Because of the importance of a normal credit flow for the health of a neighborhood, withdrawal of conventional credit from an area because of perceived high risk becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Neighborhoods will in fact fall apart without a steady flow of credit, thus "proving" to the lenders that they were right in withdrawing their credit from such neighborhoods in the first place.

For the lender there are two types of risks: (1) that the borrower will not continue payments and will default on the loan, and (2) that if the home is repossessed, its value will be less than the outstanding balance due on the loan. It is the second type of risk that relates most closely to the redlining debate. The perception of risk arises in large part from the lenders' limited understanding

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 07

of how neighborhoods work and the heightened uncertainty that comes from dealing with the unknown. Lenders know that a middle-class suburban home will continue to be surrounded by well-maintained homes and that overall housing values will steadily appreciate. An older building in an urban neighborhood is a less certain proposition. Uncertainty triggers in the lender an image of inevitable urban decline and decay. The horror stories of blighted, racially changing neighborhoods reinforce the lenders' preconceptions that all such neighborhoods are destined for the same sorry end. And the lender cannot overlook the fact that older houses require high maintenance, may be fire hazards and may be in areas with greater risks of crime and vandalism.

The appraising process plays an important role in this perception of risk. Since Illinois does not have training or certification requirements for appraisers, credentials are based on membership in one of the two national appraisers' organizations. Underappraisal of urban properties, which reduces the amount lenders are willing to loan, is commonplace. This limits the range of buyers or stretches the financial capability of lower income buyers and thereby increases the chance of default. For example, a home selling for $30,000 might be appraised for only $25,000 by the lender. This results in a huge down payment because the lender will make a loan based on the $25,000 appraisal figure. The $5,000 difference must be paid by the buyer, in addition to the down payment on the $25,000. Appraisers underappraise urban property because of their own bleak view of urban problems, especially those related to race. The standard training received by appraisers, as illustrated in the major text of the American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers, emphasizes that neighborhood decay inevitably follows racial transition. The appraiser is admonished that ". . . he must recognize the fact that [housing] values change when people who are different from those presently occupying an area advance into and infiltrate a neighborhood."

In 1977 the Justice Department reached an out-of-court settlement with the American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers (AIREA) on the charge that the organization, along with three other real estate organizations, was requiring or encouraging underevaluation of homes in racially changing neighborhoods. In the settlement, the AIREA agreed to "stop operating with preconceived negative expectations about racially integrated neighborhoods."

Investment strategies

The traditional stereotypes and preconceptions are being challenged by such urban investment programs as the Philadelphia Plan and the Neighborhood Housing Services (NHS) program, which show that housing loans in "high risk" areas can be sound, prudent, low-risk investments. The Philadelphia Plan involves the voluntary acceptance by lenders of liberal underwriting criteria and encourages community-based revitalization efforts. Low default rates have resulted. The NHS model operates in Chicago and many other cities with the support of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. Within a target area a coalition of lenders, local government and local community organizations is formed to develop a reinvestment strategy. Residents are encouraged to fix up their homes and the NHS organization brokers the loan application with participating lenders. Backed by a high-risk, revolving loan fund to finance nonbankable loans, assurance is given to lenders that the whole area is going to be revitalized, thus insuring the security of each individual loan. Most applications are indeed bankable and prove to be sound investments. Operating only in areas with previous histories of credit withdrawal because of notions of high risk by lenders, the NHS model establishes the idea that such notions of risk can be unjustified. Such recent successful efforts strongly challenge the theory that neighborhood deterioration is inevitable -- a theory that has dictated the policies of too many lenders for too long a time.

Although the use of red-inked maps to determine lending decisions can be prohibited, the problem of the urban credit crunch is more complex and defies decisive legal remedies. First of all, our urban neighborhoods need all kinds of investment and reinvestment dollars. Finding someone to blame for redlining will not solve the problem. Disclosure can document the problem but not solve it.

The newest arrow in the quiver of tactics to increase urban area investment is the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), technically known as Title VIII of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1977. The CRA required, by February 1979, that regulated financial institutions make available to the public a map showing the areas they serve and a list of the specific types of credit they are prepared to extend. It is of course too early to assess the impact of this strategy, but the underlying congressional intent is encouraging.

Congress stated in the CRA that: "Regulated financial institutions are required by law to demonstrate that their deposit facilities serve the convenience and needs of the communities in which they are chartered to do business. The convenience and needs of communities include the need for credit services as well as deposit services, and regulated financial institutions have a continuing and affirmative obligation to help meet the credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered." This emphasis on the community obligations of financial institutions is important. Besides the mandated stipulations cited above, financial institutions are encouraged to describe the methods and extent of their efforts to help meet community

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 08

credit needs. The clear intent is to break down the barriers between community groups and lenders and encourage mutual efforts to get the dollars flowing into urban areas.

Regulations

The teeth in CRA are weak, but they do have some bite. The act requires each federal financial supervisory agency to use its authority when examining financial institutions to "encourage such institutions to help meet credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered." Four federal agencies -- the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Home Loan Bank Board -- are directed to look for such encouragement in their regular monitoring as well as in granting charters, issuing deposit insurance, and authorizing branches, relocations, mergers and consolidations.

An example of how this mechanism might work is shown in the results of community organization protests over an application by a St. Louis savings and loan to expand its operation. In October 1978, even before the disclosure requirements of the CRA went into effect, the savings and loan responded to the community groups' demands and signed a loan policy agreement to:

-- expand its primary market area to include needy neighborhoods,

-- make at least $500,000 a year available in the market area for home purchase loans and $100,000 for home improvement loans,

-- contribute $10,000 annually to the local NHS,

-- disregard location or age of structure in granting loans,

-- assign a senior staff to promote urban lending,

-- hold quarterly meetings with the community groups, and

-- broaden criteria for determining credit worthiness of applicants.

No easy cures

If all lenders were this cooperative, the recurring and politically hot suggestion that lenders set specific credit allocations for their local areas would, of course, be quite unnecessary. But such cooperation is unusual, and other measures, such as the NHS model, rather than mandated community reinvestment need to be explored. Another is the "lend the lenders" approach of the 1974 Illinois Housing Development Authority program which increases investment capital to lenders making socially useful community investments. Measures to reduce exposure to risk can also help, such as reducing the lengthy and expensive processing time for foreclosure or providing partial government-backed mortgage insurance. With today's high interest rates, subsidized or lowered interest terms are also important for opening up home financing to urban areas.

There are no easy cures to the complex problems that coalesce to bring about redlining. The ultimate solution will require a delicate balance of carrots and sticks. But without discounting the reality of middle-class biases and lingering racism in the operation of our lending institutions, redlining is best countered through reinvestment strategies if the goal of "a decent home and suitable living environment for every American family" is to be realized.

John N. Collins is director of the Center for Policy Studies and Program Evaluation and associate professor of public administration and public affairs at Sangamon State University, Springfield.

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 09

|

|