|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

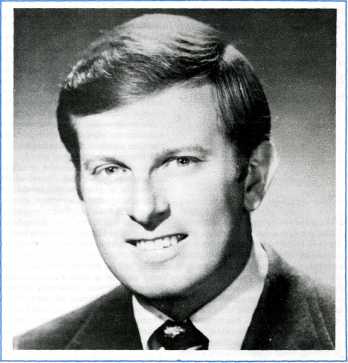

By LINDSAY GEDGE  "I JUDGE people on results." So said Peoria Mayor Richard E. Carver. The time was 1977 and Carver, who describes himself as a "most-of-the-time conservative," was discussing the nation's most powerful and politically successful mayor, Richard J. Daley. If Daley were alive today, Carver's opinion would probably be the same. "I had to admire Daley," said the boyish-looking Carver, "for his ability to do what others couldn't do." Carver, a 42-year-old Republican who is competing for the Senate seat being vacated by retiring Democrat Adlai E. Stevenson III, makes it clear that he expects others to judge him more by his accomplishments than by any hazy set of goals. Dick Carver is a shrewd, sometimes dry, eminently successful city politician whose political profile has not yet been sharply focused. The fact that he spent many years as a businessman, however, provides a clue to his philosophical mainspring: economic and political pragmatism. Carver did not inherit the wealth and influence he now enjoys. He was born in Des Moines, Iowa, where his father drove a truck for a coal and lumber business. In 1946, "Red" Carver moved his family to Peoria, where he opened his own lumber company. As a boy, young Carver helped with the small business which his father ran for a time out of the family home. Young Carver at first planned to become a lawyer because he relished the challenge of "solving problems for people." His early decisions His father welcomed the idea; young Carver was to be the first professional in the family (and remains the only politician in the family). So, in 1954, Carver and his mother traveled to Dallas, Texas, to visit the law school at Southern Methodist University, primarily because "Red" Carver believed the best opportunities for a lawyer would be found in the Southwest. But a tragic accident intervened in young Carver's career plans. Returning home with his mother three days before Christmas, Carver learned that his father and younger brother had been killed in a plane crash. Unwilling to leave his mother alone at home running the lumber company, Carver immediately dropped his plans to attend law school and took over the business. He also enrolled in business courses at the University of Iowa and later graduated from Peoria's Bradley University with a degree in business administration. Reflecting back on that decision, Carver says it was the only logical choice, as was the decision which soon followed to buy out his mother's share in the lumber company. When she remarried in 1957, Carver automatically inherited 40 percent of the company and soon bought the rest. Five years later, November 1979/ Illinois Issues/9

His youthful image and business successes encourage a comparison with young Charles H. Percy who left Bell and Howell at the peak of a successful business career to pursue political office. Carver points to his more than 20 years in business as evidence of his organizational skills. But he is quick to note that his "hands-on government experience" in city hall is even more indicative of his abilities. Carver entered elected politics as a Peoria alderman in 1969; four years later, he was elected mayor. In 1977, he was reelected, becoming the first Peoria mayor in 50 years to win a second consecutive term. Although he has always admitted his desire to seek a higher office, Carver has consistently refused to make the attempt until satisfied with his report card in Peoria. For that reason, he turned down an offer in 1976 from then gubernatorial candidate, James R. Thompson, tojoin the GOP ticket as lieutenant governor. He explains that it was "probably the right time politically for Dick Carver, but the wrong time for a city with a big renewal project." Many agree that Peoria's downtown revitalization program, which includes plans for a civic center, downtown mall and the redevelopment of another 200 acres, could not be completed, or at least not as rapidly, without Carver at the helm. He is given major credit for inaugurating Peoria's urban renewal plan in 1973 during his first year in office as mayor. Not only did he persuade the University of Illinois trustees to build a medical school adjacent to the city's low-income, high-crime neighborhoods, but he also secured federal aid for Peoria at a time when President Nixon had frozen all funds for new urban projects. Peoria was the only city to receive millions of federal dollars for its renewal program, an accomplishment in which Carver takes huge pride. Logic and luck Workers at city hall credit Carver's accomplishment to his well-developed contacts in Washington, pointing out that Peoria was not even required to make a formal application for the grant. Carver doesn't deny that claim, saying he has worked hard over the years to develop contacts which, in turn, work hard for him. But, characteristically, he says that the successful urban project "proved that if you did follow a logical sequence and get a little bit lucky along the way, you could, in fact, make something happen." "Peoria definitely gets more than its fair share," said one city official, while discussing Carver's lobbying talents. In fact, during the six years Carver has been mayor, Peoria has been awarded more than $35 million in redevelopment funds alone. The city of Rockford, which is comparable in population, has not received one third that amount, according to a program analyst at Peoria city hall. But Carver's powers of persuasion are not only effective with bureaucrats; private dollars have continued to flow into the downtown renewal effort as well. Carver hopes his reputation as a successful advocate for the nation's cities will help demonstrate his leadership qualities to Illinois voters. In June, Carver became president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors (USCM), the urban lobbying voice in Congress. Not only does Carver hold that post as a representative from a smaller city, but he is also the first Republican to head the heavily Democratic group since 1936. As spokesman for the nation's mayors, Carver was one of the few urban representatives summoned to Camp David last July to advise President Carter on domestic policy. He has made subsequent trips to the White House to speak out on such diverse topics as energy concerns and the plight of the Vietnamese boat people (the latter after Carver returned from his recent trip to mainland China). Some insiders in the Mayor's Conference, however, downplay Carver's achievement in winning the USCM presidency. They say the nominating committee had previously decided to select a Republican, and Carver was one of only a few GOP mayors who had climbed far enough up the organizational ladder to be considered. Others say he earned it. "He would have been president whether he was a Republican or Democrat," says Savannah, Ga., Mayor John Rousakis. "He is very effective in his work within the conference of mayors and has done an outstanding job as spokesman." Rousakis heads the National League of Cities, a post Carver sought and lost in 1977, But Carver sits on the league's executive board and is also a member of President Carter's Advisory Committee on Intergovernmental Relations. It is rare for a local politician from a city the size of Peoria to gain such national prominence. Carver says it will serve him well during the campaign, but some political insiders in Illinois suggest Carver is showing early signs of another Percy trait, one which almost cost the senator his 1978 reelection. They speculate that Carver's style suggests he is seeking to be Washington's representative to Illinois, and not Illinois' man in Washington. Carver rejects the comparison, saying, "All of the time that I have 10/ November 1979/ Illinois Issues spent in Washington has been articulating the problems of Peoria and American cities to gain Washington's help for those cities .... That has been my perspective and would continue to be my perspective." Carver claims his national experience has better prepared him to serve Illinois. "I go to Washington and testify on some bills, and I'm astounded at the lack of fundamental information that some members of Congress have relative to these activities." Furthermore, Carver sees no contradiction between billing himself as a conservative Republican while assuming leadership posts in traditionally Democratic organizations. He likes to compare himself to his political mentor, Sen. Richard G. Lugar (R., Ind.), "a person who tends to be conservative most of the time, but who can vote in a moderate vein on occasion simply because that seems to be the most practical path to follow." 'A family senator' Despite the sound-as-brickwork logic which Carver avows, his positions on some issues are not crystal clear. For example, when talking to Carver, one is left with little doubt that he abhors abortion because "it leads first to euthanasia, next to [killing] the severely retarded and it just keeps going," as he puts it, in his most stern voice. And yet, if elected, he says he would not support a pro-life amendment, nor can he promise he would not sanction an abortion under certain circumstances. Similarly, Carver supports the Equal Rights Amendment, but with some reservations. He feels such a proposed constitutional amendment is not the necessary or proper solution for guaranteeing equal rights for both sexes, yet he says he can't oppose a written document that makes such a statement. Such hard to understand positions are sure to surface often, as Carver seeks to build his name recognition as "a family senator." The family theme was developed in part by the Washington-based political consulting firm of Bailey and Deardourff and Associates. However, it is strikingly similar to the theme which brought Carver his first victory as mayor: to "chart a common sense course for ourselves and our children." And Carver is confident it will work again in 1980. The theme allows the candidate to present himself to Illinois voters accompanied by perhaps his most politically attractive asset: his own family. Carver's wife, Judy, and their four teenage children are as bright and burnished as the candidate himself. State roads and highways are already sprinkled with billboard photographs, showing all six Carvers leaning on a wooden, split-rail (Land-of-Lincoln) fence. But Carver says the theme is timely and was not chosen to emphasize the good looks of his family. "It emphasizes the type of experience I've had. A hands-on government situation where you're dealing with the implementation of programs instead of dealing simply with the philosophy of a program that someone else will implement. It says that when I take a look at programs, I take into account people in this country from a family perspective, alongside an employee/ employer, union/ nonunion kind of perspective." But with families all over the country loudly disagreeing on what is to be done about inflation, jobs and the environment, it is hard to define Carver's stands on some domestic issues as being "family conscious." What they do reflect is his general pragmatism. Carver, like Gov. James R. Thompson is willing to ease environmental standards to encourage increased use of high-sulfur, Illinois coal. He says he favors "a practical trade-off on the environment based on a cost-benefit basis. If the air has to be just a little dirtier, but it isn't going to create a major health hazard, I would support it." Carver also favors the increased use and development of nuclear energy. He says, "I support nuclear energy. We have to make sure it's as safe as can humanly be done," adding that government controls are too restrictive. "The bureaucracy has created tremendous roadblocks to the development of nuclear energy . . . it's costing dramatically more than it should." And although these sometimes conflicting opinions seem to reflect a candidate who is reluctant to take a stand, they also highlight Richard Carver's strongest political skill, his ability to approach decisions systematically, balancing the trade-offs, and then striking a compromise. Carver says he is a serious candidate for the Senate, interested only in winning, not in gaining name recognition for a future race. He says this is the only elected office, besides his present position, in which he would like to serve. And he is spending money on the campaign like a serious candidate. The primary alone is expected to cost $750,000. It is expected that at least one-third of the money will be in hand by December, most of it coming from supporters in the Peoria area. The money will help to pay off the $48,000 bill from Bailey and Deardourff (as well as

Although he is not a man to take a bet on bad odds, Carver admits that in addition to the huge amounts of cash, he'll need a little luck to win this race. His game plan, of course, will be to "follow a logical sequence and get a bit lucky along the way." It's worked before for him. A reporter and producer at WMBD- TV, Peoria, Lindsay Gedge is a graduate of the public affairs reporting program at Sangamon State University, Springfield. November 1979/Illinois Issues/11 |

|

|