|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

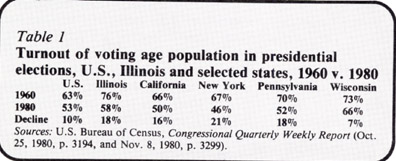

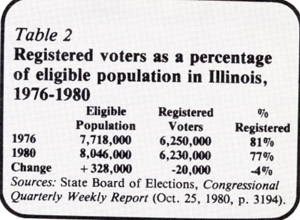

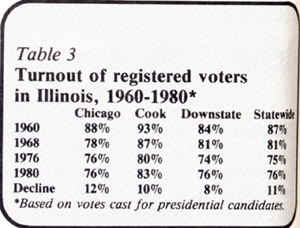

Voter turnout drops again By DAVID H. EVERSON and JOAN A. PARKER Expectations were high in Illinois for a good turnout at the polls in November. But by election day, registration of eligible voters was down in the state. The result was a 3 percent decline in voter turnout compared to 1976 THERE WAS every reason to believe that the growth of the "stay-at-home" party would be halted in Illinois and the nation in 1980. Nearly everyone anticipated a close election. The Presidential choices offered were numerous and reasonably clear. In Illinois, the polls were kept open another hour. The constitutional initiative — the so-called "Cutback Amendment" — might have been an inducement for increased turnout in Illinois. And preliminary estimates by the State Board of Elections anticipated a "record high turnout projection" in terms of total votes cast. Nevertheless, turnout of eligible voters dropped again in the nation (by 1 percent), for the fifth consecutive year, and Illinois again declined at a greater rate (3 percent). And those who did vote avoided straight-party voting, a sign that party loyalty continues to decay. Why don't Americans vote? And is the two-party system at fault? Nationally, more than a majority of eligible voters repudiated the two-party presidential alternatives in 1980. When the percentage of eligible voters who did not vote at all is added to the percentage who voted for minor party candidates, the result shows a "repudiation factor" that has grown steadily in American politics from 37 percent in I960 to 52 percent in the November 1980 election. In Illinois in 1980 the factor stood at 50 percent. Of course, the exceptionally high "repudiation factor" in 1980 was due to the independent candidacy of John B. Anderson of Illinois. He garnered 6 percent of the vote nationally and 7 percent in Illinois. And even Libertarian candidate Ed Clark received approximately 1 percent of the vote. Anderson's relatively strong independent candidacy is another sign of the weakening of the two major parties. Nevertheless, the greatest share of the increase in the "repudiation factor" since 1960, even with strong third party and independent candidacies in 1968 (Wallace) and 1980, is due to turnout decline. Staying at home on election day is a national problem, but it particularly afflicts Northern, industrialized states (see table 1). New York is a prime example. By 1980, turnout in the Empire State was lower than in 10 of 13 Southern states. No Northern state showed an increase, but at least Wisconsin had a drop of only 7 percent, which shows that the decline is not as steep in all Northern states. In Illinois, the turnout of registered voters, based on votes cast for presidential candidates, was 76 percent in 1980, actually a 1 percent increase from 1976. But since the number of registered voters had dropped 4 percent since 1976, actual numbers voting as a percentage of voting age population showed a decline. In 1976, there were 6,250,000 voters registered for the fall election, which was 81 percent of the 7,718,000 Illinois residents of voting age population, as calculated by the U.S. Census. In 1980, there were 6,230,000 voters registered for the fall election, which was a drop of about 20,000 voters. But since Illinois' 1980 total eligible voters had increased to 8,046,000, according to Census estimates, the registered voters in 1980 had dropped to 77 percent of those eligible (see table 2).

In an earlier article on turnout in Illinois (Illinois Issues, June 1979), we had noted that "decline in registration cannot begin to account for the . . . drop in voter participation. ..." That statement, however, does not hold for the 1976-1980 drop. All of the 1976-1980 decline could be accounted for by the lower proportion of registered voters in the state. This decline in registration in Illinois is also part of a national pattern as reported by George Gallup in December. A simple axiom explains the latest turnout decline in Illinois and the nation: if you ain't registered, you cain't vote. The modest 1 percent increase in the turnout of registered voters statewide was not uniform throughout the state. There was a 3 percent increase in suburban Cook County and a 2 percent increase downstate, while turnout in Chicago remained the same (see table 3). The candidacy of Ronald Reagan may have been more attractive to his natural constituents in the suburbs and downstate than was the Carter candidacy to the Democratic electorate of the city. An examination of voter registration figures for Chicago, Cook County and downstate again illustrates the significance of voter registration decline, especially in Chicago. There was a 5 percent decline in total voter registration in Chicago from 1976 to 1980, while registration in suburban Cook County and downstate was essentially the same. The decline in Chicago resulted in a 4 percent drop in the total vote cast for president from 1976 to 1980. February 1981/Illinois Issues/9 Several factors account for the erosion of the Chicago vote. The changing demographics of the city have left it with smaller population and a population which is both more difficult to register and less inclined to vote. Blacks traditionally have lower rates of registration and voting than whites and the corresponding rates for those of Spanish origin are even lower. In this particular election, it appeared that the number of registrants may have been down because no one led an effort to register Democrats. The Chicago Democratic organization was divided. Mayor Jane Byrne pulled away from endorsing Democratic state's attorney candidate Richard M. Daley and actually worked for his Republican opponent. And Carter, whom Mayor Byrne barely backed, did not motivate Chicagoans (who would normally cast Democratic ballots) to register.

Ticket splitting is another phenomenon of U.S. and Illinois elections, and it indicates a decline in party loyalty in the electorate. Ticket splitting did not seem to occur in the epic proportions of 1978, but it was evident. The results of a county-by-county analysis of election results, show voters splitting their votes between parties in the presidential and senatorial races. In Rock Island County, for example, Republican Ronald Reagan won this presidential race by a margin of 4,723 votes, yet Democrat Alan Dixon carried that county in his U.S. Senate race by 10,457 votes. In 47 of the 101 downstate Illinois counties, Republican Reagan won the presidential vote and Democrat Dixon won the senatorial one. In the Cook County suburban townships the same kind of schizophrenia occurred. In 16 out of 30 townships (53 percent), Reagan and Dixon won. Only in the Chicago wards was ticket splitting less evident: Dixon carried all 50 wards and Reagan carried only three. Another assessment of ticket splitting compares the percentage of votes cast for the party's high vote getter with that of the low vote getter. For the Democrats, the comparison is between Dixon and Carter. The difference between the high vote percentages for Dixon and the lows for Carter results in a "net" index of ticket splitting. The total vote for the downstate 101 counties shows that the difference between Dixon and Carter was 16 percent. Predictably, the differential was much greater in the suburban Cook County townships (19 percent) than in the Chicago wards (10 percent). This measure of net ticket splitting does not, of course, indicate the exact amount of individual ticket splitting. But it does suggest that, particularly in the Chicago suburbs, Ronald Reagan's coattails were not long enough to reach Dave O'Neal in his race to beat Dixon. By definition, anyone who voted for independent Anderson for president and for one of the senatorial candidates split a ticket. However, this "split" does not show up in the assessments. The vote percentages for Anderson in Chicago (5 percent), suburban Cook County (9 percent) and downstate (8 percent) showed again that ticket splitting was more frequent in the suburbs and least frequent in the city. In this analysis of voter turnout, it appears evident that party decline and voter turnout decline are linked. In recent years, there have been internal divisions in the Chicago Democratic organization with the Daley-Byrne conflict of 1980 as only the latest and most dramatic manifestation. It seems no accident that although Chicago delivered 68 percent of its vote to President Carter, this vote bonanza in the city was unable to prevent a landslide defeat statewide. That 68 percent is fewer voters than four or eight years ago, because of the loss of population in Chicago. And with fewer voters now, there is also evidence that motivation to register to vote was not provided by the Chicago Democrats. In 1976, there were 1,646,000 registered voters in Chicago. By 1980, that figure was down to 1,515,000.

Obviously, an increase in voter registration in Illinois would alleviate some of the turnout problems. A glance at table 1 shows that Wisconsin, which now practices election day registration, has had a slower rate of decline than other Northern states (Minnesota with similar registration procedures also has less decline). Election day registration would probably be politically impossible in Illinois, because downstate suspicion of potential fraud in Chicago (and vice-versa) would prevent its adoption. Perhaps other steps, such as registration by mail, or some technological innovation, could be taken. Finally, it appears there is an erosion of the "civic duty" norm connected with voting. As reported in our previous article, the "stay-at-home"party inhabits all of Illinois — city, suburbs and rural areas. Until and unless there is a reacquisition of a sense of obligation to vote, and motivation to vote (traditionally associated with loyalty to a political party), we cannot expect a turnaround in the current trend to not vote. David H. Everson is director of the Illinois Legislative Studies Center at Sangamon State University. Joan A. Parker is research associate of the center. Everson and Parker are authors of two previous Illinois Issues articles, "Ticket splitting .... "August 1979, and "Voter Turnout Decline, " June 1979. February 1981/Illinois Issues/10 |

|

|