|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

By GEORGE PROVENZANO Natural gas: What's in the pipeline for Illinois? Partial support for the energy series has been provided through a grant from the Office of Consumer Affairs of the U.S. Department of Energy. Opinions and conclusions expressed in the article are solely the responsibility of the author. Gas supplies, gas consumption and gas prices are crucial in Illinois which ranks fourth among the states in consumption of natural gas and second in the use of gas for home heating. A decade ago, gas was cheap, consumers extravagent, supplies uncertain and shortages chronic. Gradual price deregulation by the federal government changed that picture. Today gas prices are rising three times faster than inflation, consumers are conserving, and supplies are more certain. Future prospects include accelerated deregulation, higher prices, new (and more expensive) sources of gas and continued Illinois dependence on gas, especially for home heating. SATURDAY, January 15, 1977, a killer blizzard slammed into the Midwest. When the snowing stopped on Sunday, a blast of artic air and 15 to 20 mile-per-hour winds pushed temperatures down to minus 19 degrees F in Chicago and minus 20 in Springfield and Peoria. Windchill factors fell to frigid minus 55 degree levels, and radio and television announcements warned people to stay indoors except for emergencies. Additional announcements from the gas companies requested that households conserve as much heating fuel as possible. Although the utilities assured Illinois consumers that there would be sufficient gas supplies to keep residences warm, they were uncertain about the prospects of heating schools, office buildings and factories come Monday morning. Although extremely cold temperatures and high winds persisted into the week, there were only isolated disruptions in gas service in this state. In contrast to other midwestern states Ohio, in particular, where disruptions were widespread and caused prolonged work stoppages Illinois gas utilities met virtually all demands in what has to date been the severest test of their supply capabilities. More than any statistics, these events imprinted in the minds of the public an awareness of this state's great dependence upon natural gas as a source of both energy and economic well-being. As long as gas was in short supply, excessively cold winters might mean that Illinois residents could have warmth or jobs but not necessarily both.

The harsh winter of 1976-77 also marked a low point in consumers' confidence in the ability of the gas industry to supply its customers' future demands. That confidence had already been deeply eroded by nearly a decade of news of declining natural gas reserves and curtailments in deliveries by interstate pipelines. These shortfalls in supply had resulted in service cutbacks for industrial users and in waiting lists for new residential customers. In January 1977, these conditions were signs that the U.S. had become overly dependent on natural gas as a cheap source of energy. At then existing prices, gas demand greatly exceeded supply. Furthermore, many private citizens and government policymakers believed that at 1977 rates of consumption, the U.S. would fully deplete its gas reserves in about 20 years, and gas would have a declining role in meeting the nation's future energy needs. Since 1977, the public's perception of the vitality of the gas industry has changed dramatically. At the local level, increased pipeline deliveries of gas have permitted many utility companies to improve their supply capabilities and to eliminate hookup queues and other restrictions on extending service to new customers. In addition, conservation among all classes of gas users has enabled utilities to stretch their new supplies even further. In many areas the shortages of the 1970s have been forgotten, and gas is again competing as a viable alternative to other forms of energy. Perhaps the single most important reason for this reversal is the change that has occurred in the federal government's policy for regulating producer, or wellhead, prices of natural gas. Since the mid-1970s, the federal government has taken a more liberal stance on the size and frequency of wellhead price increases. After a two-year battle, Congress cemented many features of this policy shift into the Natural Gas Policy Act (NGPA) of 1978. This act, which is administered by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), is the main instrument by which the federal government regulates the gas industry. Higher wellhead prices have stimulated a major increase in the exploration and development of conventional natural gas resources. Higher gas prices have also increased the attractiveness of developing the vast potential of supplemental supplies such as natural gas imports, natural gas production from nonconventional resources and synthetically produced gas from coal and other feedstocks. Finally, higher wellhead prices, when passed on to consumers, have encouraged conservation and have caused the overall level of gas consumption to decline from its peak in the early 1970s 6/February 1982/Illinois Issues The net result of these trends is that today, in direct contrast to just five years ago, the view of many energy experts have turned completely around regarding the gas industry's ability to continue to meet future energy demands in Illinois and throughout the rest of the country. In fact, several government and industry energy forecasts now project increases and not declines of from 10 to 50 percent in total U.S. gas consumption in the year 2000 compared to what it was in 1980. The industry The natural gas industry consists of four segments: ultimate consumers of gas such as residences, commercial establishments and industrial facilities; local gas utilities or distributors that sell gas to ultimate consumers; pipeline companies that transport gas from producing areas to consuming markets; and producers that find and develop natural gas resources. In 1981-82, barring an uncommonly warm winter, over 3.25 million residential, commercial and industrial customers in Illinois will purchase nearly 1,000 billion cubic feet (BCF) of gas. Gas will satisfy approximately 28 percent of Illinois' primary energy needs, which is a slightly higher percentage than for the nation as a whole. Seven of Illinois' 19 investor-owned utilities will distribute over 98 percent of these purchases and will collect an estimated $3.6 billion in gas bills for their services (see figure 1). The areas that these companies service within the state and the rates they charge are regulated by the Illinois Commerce Commission. Although Illinois ranks fourth among the states in consumption of natural gas, only a very tiny fraction of the state's needs are produced here. Local gas utilities purchase their gas supplies from several interstate pipeline companies that are interconnected into a national gas transmission network. The pipelines in turn buy gas from producers under long-term contracts for specific levels of production from dedicated gas reserves. The prices for these wholesale gas transactions between pipelines and producers are regulated by the FERC.

Most of the gas that is consumed in this state comes from major producing regions in the Panhandle area of Texas and Oklahoma and the Gulf Coast area of Texas and Louisiana. Gas from Canada and newly discovered fields in the Rocky Mountains is also transported into Illinois through the interstate pipeline network. Major oil companies have also begun construction of a 4,800-mile pipeline that is scheduled to bring gas from Alaska's North Slope through Canada to Dwight, Illinois a major "interconnect" point in the nation's gas pipeline network by the late 1980s. This project, which has an estimated price tag of $43 billion, recently has attracted a swarm of controversy. In December as part of a package of financial sweeteners for the project, Congress enacted legislation allowing the pipeline's sponsors to charge consumers the full cost of building each segment of the line as it is completed. This pre-billing measure means that consumers will be paying for a transmission system even before it delivers any gas. In fact, even if the system is never completed, or if the gas proves too expensive to market, the consumer will still bear the full costs of whatever portions of the system are built.

Since most gas is consumed during the peak heating season, Illinois utilities make extensive use of underground gas storage in order to balance winter and summer operations. Illinois utilities currently operate over 30 of these storage fields dispersed throughout the state. The fields have an approximate storage capacity of over 80 percent of the state's current annual demands. In addition to pipeline supplies, both Northern Illinois Gas Company and People's Gas, Light and Coke Company produce supplemental gas supplies at two synthetic gas plants near Chicago. These plants make methane, the primary constituent of natural gas, from natural gas liquids and naphtha and have the capacity to produce up to 10 percent of Illinois' annual needs. However, because of high feedstock costs, this Illinois-produced gas is considerably more expensive than pipeline gas. Consumption Because of its convenience and its clean combustion properties, most of the natural gas that is consumed in Illinois is burned directly, in contrast to coal which must first be converted into electricity. Residential and commercial consumers use gas for space heating, water heating and cooking purposes. February 1982/lllinois lssues/7

Large industrial consumers use gas as a boiler fuel in producing process steam and as a raw material in the manufacture of plastics, fertilizers and other chemicals. Finally, electric utilities purchase small amounts of gas, generally on an interruptible basis, to generate electricity. Illinoisans currently use natural gas to satisfy more than 50 percent of the energy needs of their homes. Large quantities of gas are also used in the state's commercial and industrial establishments, but the current relative importance of gas as a source of energy for these sectors is substantially less than for the residential sector. In 1980, residential gas sales accounted for the largest component (46.9 percent) of total gas demand in Illinois (see figure 2). In terms of dollars, these sales were the largest of any state in the country. In terms of volume, they were second only to California. Nonresidential gas sales in 1980 were divided among commercial and industrial customers with space-heating service (31.0 percent), without space-heating service (19.6 percent) and with interruptible service (2.5 percent). This last service category refers to gas sales that are made on a standby basis. Although total gas consumption in Illinois was virtually the same in 1980 as it had been in 1970, the composition of demand changed in several important ways during the intervening 10 years. Despite the presence of chronic gas shortages during the 1970s, spaceheating demands in both the residential and commercial sectors rose steadily and in a manner that outpaced national trends. In the residential sector, Illinois gas consumption per capita increased from 1.5 times the national per capita consumption level in 1970 to over two times the national level in 1980. These increases were offset by declines in industrial gas demands. During the 1970s, many industrial customers cut back on gas use and switched to other fuels because of concerns over service curtailments and higher gas prices. Of greater significance is the fact that the number of residential and commercial space-heating customers increased by a substantially larger percentage than did demand in those service categories. Again, in the residential category, total demand increased by 13.6 percent while the number of customers rose by 25.6 percent, indicating that Illinoisans have become even more widely dependent on natural gas for meeting the wintertime energy needs of the home (see table 1). These new residential customers have come primarily from two sources: new housing construction and conversion to gas from home-heating oil. The latter currently accounts for a majority of new gas hookups in Illinois. Historically, gas has cost less than heating oil for space-heating purposes, and heating oil has cost less than electricity. Even in the early 1970s, heating oil was as much as 25 percent more costly than gas on a per-million-British-thermal-unit (MMBtu) or heat-equivalent basis. Since the OPEC oil embargo of 1973, the price of home heating oil has increased much more rapidly than the price of gas and is now over twice as expensive per MMBtu. This price differential has sharpened the longstanding incentive to convert oil-heated homes to gas. Between 1977 and 1979, as the availability of gas improved, the number of households in the U.S. that annually convert from oil to gas quadrupled and has, in fact, returned to pre-gas-shortage levels. Most of this recent upsurge in conversions is a reflection of pent-up demand for residential gas service in the heavily populated states in the Northeast and Midwest. In 1979, Illinois had more oil-to-gas conversions (61,600) than any other state and accounted for one-sixth of the estimated national total. 8/February 1982/lllinois Issues

The increase in the number of customers served by roughly the same quantity of gas would not have been possible without conservation. Conservation has enabled gas utilities to spread available supplies more thinly in all customer categories but most notably in the residential sector. By 1980, residential gas consumption per customer had declined by 14 percent from its peak level in 1972. When measured in a manner that adjusts for annual differences in weather conditions, gas demand has declined nearly 23 percent during the same period (see table 1). Although gas conservation was a significant factor in balancing gas supply and demand in the late 1970s, conservation-induced reductions in gas consumption are likely to continue at a slower pace in the 1980s. To date, a large part of the per-household decline in residential gas consumption has come about through "primary conservation measures," methods of reducing energy demand through no-cost or low-cost changes such as lowering thermostats, caulking and weatherstripping. The opportunities for fuel savings through primary conservation are rapidly diminishing. A substantial portion of the remaining gains in gas conservation now lies in adopting secondary conservation measures such as installing storm windows, fuel-efficient heating equipment and large amounts of insulation. All of these measures cost more than primary methods, and people are likely to act more slowly in implementing them. Prices Rapidly increasing monthly gas bills obviously have been instrumental in encouraging this degree of conservation. From 1975 to 1980, average residential gas prices nationwide increased at an average annual rate of nearly 17 percent. Since the enactment of the Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978 (NGPA), gas price increases have accelerated and are now in the 25 to 30 percent range, which is over three times the current rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index. Because of the NGPA provisions, consumers can expect this trend to continue through the mid-1980s. As one of its main features, NGPA established a series of maximum lawful wellhead prices for different categories of newly discovered natural gas. These ceilings are allowed to increase automatically February 1982/Illinois Issues/9 In 1979 Illinois had more oil-to-gas conversions than any other state. But conservation by consumers has enabled utilities to serve more customers with roughly the same supplies each month with inflation. For some categories of so-called difficult-to-produce gas (for example, gas found below depths of 15,000 feet), wellhead prices are allowed to increase at rates which are somewhat faster than inflation. Although NGPA ceilings are complex and now cover more than 20 different classifications of gas, the system can be understood as basically involving three categories: old gas, new gas and uncontrolled gas. Old gas, for the most part, comes from wells that were producing prior to April 1977; new gas, for the most part, is from wells that have been producing since that time. The uncontrolled or deregulated category is for specifically defined types of reserves that are more costly to develop. Most gas reserves are in the old or new categories. Under NGPA, price ceilings for most categories of new gas are scheduled to be deregulated on January 1, 1985. Old gas, which will then make up over 40 percent of total supply, will continue to be controlled until it is depleted; after 1985, the prices of old gas will be allowed to rise at a rate slightly higher than the general inflation rate. As a consequence of federal regulation, wellhead prices vary tremendously, depending on when the gas was discovered and offered for sale. Gas that is being sold under long-term contracts negotiated prior to 1973 may be selling for as little as 40 cents per 1,000 cubic feet (MCF). Gas that is being supplied from new wells under contracts negotiated this year may be selling for $2.67 per MCF or, if it is so-called high-cost gas produced from tight formations, it may be selling for as much as $4.73 per MCF or more. In terms of contracts, the mixture of gas being delivered to local utilities at any time is constantly changing. And as low-price "old" gas reserves are depleted and replaced with "new" high-priced gas, the average wholesale or "citygate" price paid by a utility to its pipeline supplier obviously will increase. Contracts for old gas that date from the 1940s, '50s and '60s, when the market for gas was soft, are now a thorn in the side of producers. In those days, to attract new customers, particularly in the interstate markets, producers locked themselves into agreements to supply gas at cut-rate prices for periods of 20 years or more in some cases, for the producing life of the gas reservoir. Because these contracts no longer reflect the realities of gas supply and demand, many producers are asking their customers to renegotiate the prices of these old agreements. Although they are not anxious to pay higher prices, many pipelines and utilities are willing to renegotiate in order to obtain extra supplies and/or extension or renewal of their current gas deliveries. As a consequence, wholesale gas prices are currently increasing at rates that are much greater than those initially anticipated under NGPA. As citygate prices increase, gas utilities shift these increases forward to consumers through "Purchased Gas Adjustment Agreements" or PGAs. PGAs allow utilities to recover changes in the wholesale price of gas on a dollar for dollar basis.

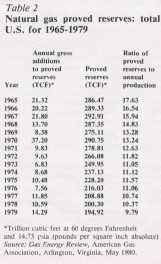

NGPA's future, at least in its present form, is uncertain. President Reagan campaigned as a strong proponent of decontrolling all natural gas prices. After many delays and changes, his Secy. of Energy James Edwards announced in November a plan to control the prices of both old and new gas by 1986. If Congress approves these changes, the market forces of supply and demand will determine gas prices. This means, in the opinion of many experts, that retail gas prices are likely to rise even more steeply than they would under NGPA (see "Natural gas prices: from regulation to decontrol," pp. 8-9). Supplies Because Illinois depends almost exclusively on out-of-state sources for gas, its gas supply outlook depends on the outlook for the U.S. as a whole. The national supply outlook in turn depends primarily on the extent of remaining conventional natural gas resources that can be recovered economically and on whether the costs of con-ventional and supplemental gas supplies will be competitive with the costs of using other forms of energy. Domestic conventional gas resources continue to be the most important source of gas for U.S. consumers Buoyed by higher wellhead prices, producers have been drilling at a record pace for these resources in all parts of the country but especially in Alaska, the Rocky Mountain states and off-shore along the California coast, the Gulf of Mexico and the East Coast. These exploration-drilling efforts have produced a marked upturn in annual additions to proved reserves since 1977 (see table 2). As a result, a growing number of energy experts are saying that U.S. gas resources could bridge the transition between the nation's current dependence on foreign oil imports and its future reliance on domestically available sources of energy such as solar power, nuclear power or synfuels from coal. In other words, in some circles natural gas has replaced coal as the "swing fuel" in the race for energy independence. Many gas industry officials, however, are not so optimistic. They doubt that there are extensive but still undiscovered gas resources. They also point out that stepped up exploration and discovery has slowed but not reversed the decline in U.S. proved reserves which has persisted since 1968 (see table 2). This decline has fostered the widespread belief that the nation is running out of natural gas, a belief that will continue as long as annual gas production exceeds annual additions to proved reserves. 10/February 1982/Illinois Issues In the jargon of the gas industry, "remaining recoverable resources" refer to those quantities of gas which can be extracted under existing technological and price-cost relationships, assuming normal short-term growth trends. Remaining recoverable resources include reserves and potential resources. "Reserves" are recoverable resources whose existence is known with reasonable certainty as a consequence of exploration and which are producible under current economic and operating conditions. "Potential resources" are recoverable resources whose existence is estimated from geological, geophysical and engineering data. Just how much gas there is left to discover and produce in the U.S. is, of course, a matter of considerable speculation among experts in industry and government. In the last 10 years, several assessments of available data have resulted in estimates ranging from 400 to 1,200 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of recoverable gas resources. At current rates of consumption (20 TCF annually), these volumes would supply the nation for an additional 20 to 60 years. The reader should note that these estimates are obviously subject to a great deal of uncertainty. In order to deal better with this uncertainty, the Potential Gas Committee, an industry-sponsored group of experts, has subdivided its most recent estimate of 913 TCF of potential gas resources into three categories: probable (193 TCF); possible (358 TCF); and speculative (362 TCF) (see figure 3). "Probable resources" are the most likely to be discovered in that they are associated with further development in gas fields that have already been discovered. "Possible resources" are next in likelihood; these are estimated to occur in fields to be discovered in provinces having similar types of geological formations to those from which natural gas has been produced. "Speculative resources" are the least likely to be discovered; they are estimated to exist in provinces where no gas production has been established or in formations having no previous history of being productive.

Higher prices for newly discovered natural gas have also increased the prospects for timely development of "supplemental gas supplies," which the gas industry regards as including all sources other than natural gas production from porous sandstone formations within the lower 48 states. Supplemental supplies currently account for less than 7 percent of total U.S. supplies. According to the American Gas Association, however, this percentage will rise over the next 20 years so that by the year 2000, supplemental sources may contribute from 40 to 60 percent of total supply. The increase in supplemental supplies will come from a variety of sources: pipeline imports from Alaska, Canada and Mexico; imports of liquified natural gas (LNG) from Algeria and elsewhere; domestic unconventional resources in tight sandstone reservoirs, Devonian shale deposits, coal seams and geopressured aquifers; and synthetic natural gas (SNG) produced from coal, oil shale and biomass. Although having commercially available technologies to produce supplemental supplies is the necessary condition for their use, the sufficient condi-tion is that the costs of using supplemental gas remain competitive with the costs of using other fuels. The future Sometime during the 1980-2000 time frame, these supplemental gas supplies will become available; exactly when is a matter of economics, technological development and national energy policy. Because of their low cost relalive to oilier supplemental sources, pipeline imports are and will continue to be the predominant supplemental source during the 1980s. Domestic gas resources such as tight sands and Devonian shale, which require technological advances for economic extraction and are therefore more costly, will achieve greater importance in the 1990s. Finally, coal gasification is likely to become an important supplemental source by the late 1990s, but because of the relatively expensive capital investments needed for this technology, the extent of its contribution will probably depend on how much the federal government is willing to subsidize its development. Meanwhile, gas continues to be the least costly fuel for meeting rnany energy needs. This advantage has persisted through a period of chronic shortages in the mid-1970s and a period of rapidly rising gas prices in the late '70s and early '80s. As a result, Illi-noisans are more dependent than ever before on natural gas. But even as many U.S. consumers convert to gas from oil, the price differential between gas and other energy sources is clearly bound to shrink. Nevertheless, it ap-pears that because of its relatively stable cost of transportation via pipe-line, natural gas will remain cheaper for consumers than most alternative fuels. By the end of the 1980s, there-fore, Illinoisans are likely to rely even more on natural gas than they do to day. George Provenzano is an economist with the Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. 12/February 1982/Illinois Issues |