|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

New open meetings law: visions and revisions By DONA GERSON In existence since 1957, the Illinois open meetings law continues to suffer from a lack of definition. Enacted to prevent important decisions from being made without public scrutiny, the law and its newest revisions may have other unintended results, especially at the local level

"TALKING to local officials about open meetings is like talking to rabbits about planned parenthood. It's hard to get their attention,'' said one observer. But there is no question of attentiveness today because significant changes in Illinois' open meetings law went into effect on January 1, 1982. The amendments seek to strengthen and clarify the law, but some critics warn of problems ahead. This is the third generation of open meetings laws in Illinois. A law regulating the meetings of public agencies was first enacted in 1957. Substantial amendments were made in 1967, how ever, including this statement of public policy: It is the public policy of this State that the public commissions, committees, boards and councils and the other public agencies in this State exist to aid in the conduct of the people's business. It is the intent of this Act that their actions be taken openly and that their deliberations be conducted openly. The Illinois Supreme Court cited this policy when it ruled in December 1980 in the case, People ex rel. Thomas J. Defanis, State's Attorney v. Joan Ban et al., that the law covered informal as well as formal meetings. "This clearly enunciated public policy" would be poorly served, according to the court, if an informal caucus of nine members of the Urbana City Council were regarded as an exception to the open meetings requirements. Noting that the 1967 amendments deleted the word official before the word meeting, the court stated, "Palpably, the amendment was intended to include unofficial or informal meetings within the Act."

This case of the so-called Urbana Nine pointed up a critical problem for every member of a county, city, village, township, school district or special government board. And that problem was that while the more than 40,000 local officials in Illinois knew they were required to have open meetings, there was no definition of meeting. The law didn't define it. Former state Rep. Anthony Scariano of Park Forest (so closely identified with the 1967 amendments that they are often referred to as the Scariano law) said that the General Assembly chose not to define meeting in 1967. Scariano said it decided to leave the definition up to the courts. That surely created confusion for local officials. Thirteen years later there was no consistent definition arising from the appellate court cases, and local officials who were subject to penalties — modest Class C misdemeanor penalties it's true, but nonetheless criminal penalities — were not really sure when they might be violating the law. Even in its 1980 decision, the first it had rendered on the 1967 open meetings law, the Illinois Supreme Court did not define meeting, and it specifically restricted the potential scope of its decision. While a majority of the court found that the pre-arranged meeting of nine members of the then 14-member Urbana City Council violated the law, it also stated, "Whether the Act applies to other meetings and whether it is constitutional in other settings or as applied to other public officials must await further determination." This left the members of the more than 6,500 governments in Illinois, their municipal attorneys and the vitally interested news media to speculate whether the "decision under the narrow facts presented" was or was not analogous to other situations in other governments in Illinois. If the Illinois Supreme Court had defined meeting, it would have made life much easier for Tyrone Fahner, who was appointed Illinois attorney general at the end of July 1980. Within two weeks he issued an opinion on the open meetings law, an opinion that related to notice requirements for closed meetings but did not attempt to define meeting. Fahner's much criticized opinion was that legally closed meetings did not require prior public notice. Februury 1982/Illinois Issues/13 While this opinion may have been outside the philosophy of open meetings, it was inside the language of the Illinois law, according to Fahner; but when eyebrows were raised, Fahner said, "Let's get to work on revising the law," and he did, immediately. That meant grappling with all of the complexities inherent in the definition of meeting. Was it a meeting if two school board members had lunch together? If three aldermen met at a party? It was a hot potato, and Fahner had caught it. Need for changes In addition to the need for a definition of meeting, there were other problems with the 1967 open meetings law. For one thing, the law allowed closed meetings when a pending court proceeding was being discussed but made no provision for instances where litigation was very likely. For another, the law, which requires public bodies to give annual notice of the dates, times and places of regularly scheduled meetings and 24-hour notice of special meetings, had no provision for emergency meetings. Then there was the matter of penalties. Criminal penalties had simply never been applied in Illinois. And while the court had the authority to issue a writ of mandamus, cases often arose after an alleged illegal meeting when a writ would be meaningless. Some felt that other sanctions should be considered. Possibly the strongest indication of the need for improving the open meetings law were the endless inquiries, calls and questions received at every office where a public official or a representative of the media might reasonably expect to find an answer. Defining meeting The 1967 Illinois law required that deliberations as well as action be taken openly. But since the term meeting was undefined, the number of members of a public body who could gather together for any purpose was uncertain. Originally Fahner suggested that any gathering of two or more members of a public body constituted a meeting. But the threshold of two was criticized and "a majority of a quorum" was substituted. Ultimately, the definition which was incorporated into the law attempts to combine a quantitative standard with intent: "Meeting means any gathering of a majority of a quorum of the members of a public body held for the purpose of discussing public business." Note that the word discussing and not deliberating is used.

A majority of a quorum is a new concept. The theory is that since a quorum can act on behalf of the governing body, a majority of a quorum is sufficient to carry a motion. But there may be problems with this new quantitative measure. Rep. Dwight P. Friedrich (R., Centralia) noted in debate on the floor that the city councils in downstate areas consist of a mayor and four council members. Therefore, a quorum is three and a majority of a quorum is two. Friedrich said that it's common for them to get together for lunch, and it would be absurd to require them to call the media every time two of them sat down to eat. Yet a strict interpretation of the new provision might demand that. He suggested the threat of criminal action will make it difficult to get responsible people to run for office. Rep. Jim Reilly (R., Jacksonville), chief sponsor of the Fahner bill, H.B. 411, responded that intent is the crucial element. If members of a public body do not meet for the purpose of discussing public business or use a social occasion as a cover for discussing public business, Reilly said they "can drink all of the coffee they want." Rep. Steve Miller (R., Danville) asked, "Is specific intent an element that would need to be proved to prove a violation of this Act?" Reilly said it would. However, at another point in the extensive colloquy that accompanied passage of H.B. 411 in the House, Reilly said that the intent could develop at the social occasion itself The list of public bodies covered by the newly amended open meetings law appears exhaustive with one significant exception — the Illinois General Assembly. The law says: "Public body" includes all legislative executive, administrative or advisory bodies of the state, counties, town-ships, cities, villages, incorporated towns, school districts and all other municipal corporations, boards, bureaus, committees or commissions of this State, and any subsidiary bodies of any of the foregoing including but not limited to committees and subcommittees which are supported in whole or in part by tax revenue, or which expend tax revenue, except the General Assembly and committees or commissions thereof. This apparent direction to "Do as I say, not as I do" is shocking to many, especially considering the moralistic tone that permeated the discussion of the open meetings legislation. If it is the public policy of this state that deliberations and actions be taken openly, why is the General Assembly excepted? Supporters of this exception claim that the General Assembly is governed by the more stringent limitations of the Illinois Constitution which requires a three-fifths vote to close any meeting of either house. But that completely sidesteps the major issue which arises from that old bugaboo, the definition of meeting. Gatherings of a rnajority of a quorum of the General Assembly for the purpose of discussing public business are frequently not open to the press or public. Closed caucuses, gen erally along party lines, go on constantly and conspicuously in the General Assembly. That's where many decisions are made. Such political caucuses are an integral part of the American political process at every level of government, and the new open meetings law, while exempting the state legislative caucuses, poses a serious threat to those at the local level. Political science professor Dick Simpson of the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, who served two terms in the Chicago City Council, feels that caucuses must be protected at all levels. "There is a need to caucus to frame legislation and discuss strategy," says Simpson. "A caucus is necessary so members can know in advance what motions will be made .... if the other side knows yours strategy, they can block you. What is important to the public is the final debate, not the tactical decisions made in strategy sessions." Simpson thinks a strong open meetings law is of prime importance to prevent secret meetings, but he feels it is at least as important to also acknowledge and protect the right to caucus. 14/February 1982/Illinois Issues "A caucus allows for give and take," says political science professor Samuel K. Gove, director of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Open meetings laws that prohibit caucuses at the local level have "gone too far," according to Gove. Arnold Blockman, attorney for the Urbana Nine, discussed the need to caucus in the brief he prepared for the Illinois Supreme Court: From a policy standpoint, a party caucus of some council members is too far remote in the decisionmaking process to be subject to open meeting legislation. Politicians need to be able to privately accumulate information, privately sample public opinion, and privately discuss the political ramifications for possible programs in order to effectively perform their public functions. Many people feel that the threshold number for a meeting should be set at the quorum level (as it is interpreted in Ohio, New York, Kentucky, Michigan, Nevada, Oregon, Tennessee, Arizona and Idaho) or that the right to caucus should have been explicitly stated (as it is in Connecticut). Both the right to caucus and the right to preliminary consideration could have been protected if a distinction between deliberation and discussion were delineated as proposed by Arthur M. Sussman in his article, "The Illinois Open Meetings Act: A reapraisal" (Southern Illinois University Law Journal, 1978, No. 2, p. 221). Sussman writes: I submit that if we desire quality in our public decisionmaking, we must be willing to accept the need of government for privacy during the preliminary stages of decisionmaking. However, the new definition of meeting specifically refers to a "gathering ... for the purpose of discussing public business." Closed meetings In some instances, the reasons for open meetings — the right to information and participation, the access of the media — are overridden when the public purpose would be better served by confidentiality in such cases as the purchase of property by a public body. And privacy is regarded as more important than the public's right to know in cases involving public employees or officers, or in cases of student discipline. A Senate amendment to H.B. 411, which was adopted, allows an additional exception for commission forms of local government so that cities such as Springfield and East St. Louis may deal with executive or administrative responsibilities in closed sessions. Without this exception, day-to-day business operations would be nearly impossible given the new definition. A more significant change which affects every local government allows a closed meeting for discussion of litigation that is pending or when such action is probable or imminent. These new words in the law are not intended to open Pandora's box. Rep. Harold A. Katz (D., Glencoe) of the Democratic Minority Task Force which put forth this idea, made certain the legislative record included the intent of the drafters when he posed a pointed question to Rep. Reilly during House debate: Katz: "What would prevent a public body from meeting privately as a matter of routine with legal counsel to discuss just about any public matter because potential litigation could emerge from almost any type of discussion?" Reilly: "It's clearly the intent of the language to mean that only potential litigation of a specific nature can be discussed at a closed meeting .... It is not the intent of the legislature that a public body can meet in closed session simply because its attorney is present and on the mere assumption that something might emerge during the discussion involving 'potential litigation.'"

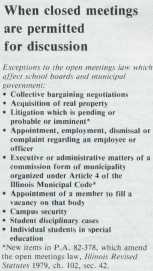

February 1982/Illinois Issues/15  The new law makes clear that the only exceptions to open meetings are those which are specifically stated: "Only those portions of any meeting expressly enumerated herein as exceptions may be closed. No final action may be taken at a closed session." Other than the two changes pertaining to city commission governments and pending litigation, the list of exceptions is identical to that in the 1967 law. School officials unsuccessfully advocated an additional exception for sale of property. Notice and minutes Although closed meetings are allowed for specific purposes, the new law requires public notice of all meetings, open or closed. A closed meeting may be held only after a recorded vote of a majority of a quorum taken at an open meeting for which notice has been given. The law requires the vote of each member and the citation to the specific exception authorizing the closing of the meeting to be recorded in the minutes of the open meeting. Another new provision requires that the 24-hour notice of special, rescheduled or reconvened meetings must include the agenda for the meeting. The new law also acknowledges the need for meetings in the event of a bona fide emergency. The law requires "that notice of an emergency meeting shall be given as soon as practicable, but in any event prior to the holding of such meeting, to any news medium which has filed an annual request for notice. While most of the changes in the law clarify and make more precise the requirements that already existed, there is a totally new provision for written minutes of all meetings, open or closed. The minutes required are minimal: the date, time and place of the meeting; the members recorded as present or absent; a general description of all matters proposed, discussed or decided; and a record of any votes taken. Minutes of open meetings are to be available for public inspection within seven days of the approval of such minutes by the public body. The public body may make minutes of closed meetings available if it determines that confiden tiality is no longer necessary. Or a court could order the public body to make available portions of the minutes of a closed meeting. The minutes requirement has raised concerns about what must be revealed in the minutes of a closed meeting and about the burden of record keeping in general, especially for small municipalities. In an attempt to clarify a potential problem, Katz asked during debate whether the minutes of a closed meeting between the attorney and the public body to discuss a legal action that is probable or imminent must identify the party involved. Rep. Reilly said no. There may be other problems with interpretation although a technical or partial noncompliance with the minutes requirements apparently would not invalidate actions taken by the public body. Given the complexity of many elements of the new provisions, there are endless possibilities for violations. Yet one of the difficult problems with open meetings laws in Illinois and other states is finding the proper means of enforcement. As noted above, the criminal penalty has never been imposed in Illinois, but that is not unique. Criminal sanctions are the "most common and least useful sanctions" found in open meetings laws, according to Douglas Q. Wickham in his article, "Let the Sun Shine In!" (68 Northwestern University Law Review, 1973). Extensive research by Wickham failed to uncover a single open meetings case involving criminal prosecution in any state. The new Illinois law, however, contains a significant new provision authorizing the court to grant injunctions against future violations of the act. Another legislative boobytrap concerned the validity of local government contracts and bond sales. If local government action can later be declared null and voil because it took place at an "illegal meeting," contractual parties and bondholders could be severely damaged. To prevent any doubt, the new law makes clear that final action taken in compliance with the open meetings law is valid even if earlier actions in regard to the matter were taken at a meeting which was in violation of the law. The new law places a 45-day time limit from an alleged violation to the filing of a civil action in court. A citizen who files suit against local officials and prevails may be reimbursed for attorney fees and court costs. To inhibit the overzealous, the act provides that legal costs may be assessed against the private party if the court determines malicious or frivolous intent. At the conclusion of long deliberation in the House on the new open meetings legislation, Rep. Reilly said "We are not in any way trying to hurt local government officials. In my honest opinion, this Bill makes it easier for them because they will understand what the Act means, when they can, when they can't meet in public ...." Rep. John T. O'Connell (D., Western Springs) said, "There is probably no more thankless job in this State than being a local official." He further added, "I think this Bill will present more harassment for local officials and be more of a deterrent for encouraging people to run for offices." The bill passed the House and Senate in July with far more than the three-fifths vote required. The law, Public Act 82-378, took effect on January 1, 1982.

Postscript Amendments to the open meetings law passed the General Assembly in a year when many significant bills floundered. Atty. Gen. Fahner worked for its passage. The Illinois Press Association, long an advocate of a stronger law, capitalized on Fahner's interest and on the insecurity of legislators who want to stay on the right side of a good 16/Febuary 1982/Illinois Issues government issue when they face newly drawn legislative districts. In addition to editorials supporting changes in the open meetings law, editors phoned legislators. Their message included more than the merits of the pending bill. One legislator reported that he and others received calls with a thinly veiled threat of editorial opposition in the next election if they failed to support the bill. In other words, the press lobbied, as do other special interest groups, with all the pressure and persuasion tactics available to them. Sara Bode, president of the Village of Oak Park, has strongly criticized the new law. "Loads of us local officials work very hard and do our best to fulfill the responsibilities of office in the face of severe limits and stringent controls," says Bode. "For heaven's sake, don't act to limit us more." But Atty. Gen. Fahner, pleased to take credit in an election year for the new law, suggests that "discomfort at conducting the public business in public . . . shows a lack of intellectual ability." Douglas Wickham, a strong proponent of open meetings laws, described the inherent conflicts in his 1973 law review article: Especially in the early stages of working out a particular problem, it makes a good deal of sense for any governmental body to retain a zone of privacy within which its members can air internal disagreements. A position, once publicly taken, is not easily changed; and it seems undesirable to encourage theadoption of "first thoughts" by requiring that all collective governmental thinking be done in public .... The value competing against "a right to know" then is not a "right to secrecy" but an assurance of some insulation from the intense heat of public pressure. Priorities must be determined, decisions made and programs implemented. Absolute openness will detract from the overall public interest in informed and rational governmental decision. |