|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

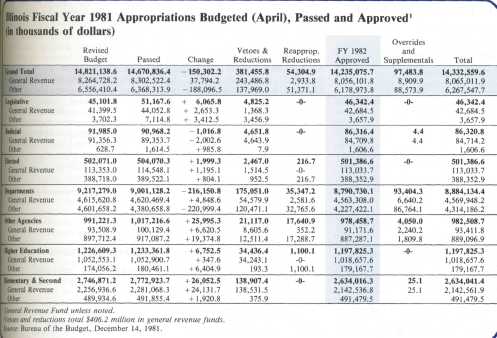

Legislative Action Appropriations: no highs and new lows By DIANE ROSS THE APPROPRIATIONS picture for fiscal 1982 has finally come into focus. The process started last March and ended in November, and the results are record breaking not for increases but for decreases. The total is less than the governor requested and less than what was appropriated the year before. As usual, the total appropriated from all funds for 1982 is more than what was actually spent in fiscal 1981, but the appropriations from general funds are less for 1982 than what was actually spent from those funds in fiscal 1981. The latter is unusual, and indicates the revenue side of the picture for the general funds is sagging. For the record, the final appropriations or spending ceiling for fiscal 1982 is set at $14,331,074,000, including $8,065,011,000 in general funds. The total appropriation for all funds is 3.3 percent less than Thompson's final budget request last April, and it is 2.4 percent less than Gov. James R. Thompson's final budget request last April, and it is 2.4 percent less than the $14,685 billion final appropriation for fiscal 1981. The 1982 total, however, is 20.7 percent or $2.4 billion higher than the $11,873 billion actually spent in fiscal 1981. (The fiscal 1981 figures are from the comptroller.) In the crucial general funds, the final figure for appropriations is $8,065 billion, which is $199.7 million or 2.4 percent less than Thompson's April budget request. And the fiscal 1982 general funds appropriations are $269.5 million or 3.4 percent above the $7,795 billion finally appropriated in general funds for fiscal 1981. But, more importantly, general funds appropriations are $107 million or 1.3 percent under the $8,172 billion actually spent in fiscal 1981. A few reminders before continuing the recap of the 1982 appropriations picture. First, appropriations are not spending per se; they are the ceiling on spending. Appropriations for any given year usually run about 30 percent ahead of spending for the preceding year, mostly because of ongoing capital projects. (Enough money to cover the remaining costs of ongoing capital projects must be appropriated in any given year whether or not the projects will be completed that year.) In addition, the appropriations picture must focus on general revenue funds, not just the overall appropriations, because the general funds are crucial to understanding the financial shape of the state; they represent the state's "real budget." The general funds represent about 70 percent of all revenue from all sources and about 77 percent of revenue from state sources chiefly (84 percent) from the income and sales taxes. And the general funds represent about 73 percent of all spending. On to the recap. For general funds, the final fiscal 1982 appropriation is $8,065 billion less than Thompson requested and less than spent in fiscal 1981. In early March, Gov. James R. Thompson unveiled a budget that called for the Illinois General Assembly to appropriate a total of $14,934 billion, including $8,342 billion in general funds. (See "Fiscal 1982: no ballast in the budget and stormy weather ahead," May 1981, p. 9.) By late April, however, citing the recession and Reaganomics, the governor revised his budget, cutting $113 million, including $78 million in general funds. This revised budget called for the legislature to appropriate $14,821 billion, including $8.264 billion in general funds. Overall, Thompson's revised fiscal 1982 budget was only $355 million, or 2.4 percent, more than the $14.466 billion he asked legislators to appropriate for fiscal 1981. It was a tiny $138 million (less than 1 percent) over the $14,685 billion finally appropriated for fiscal 1981. But compared to actual spending in fiscal 1981, Thompson's revised budget appropriations for fiscal 1982 were $2.95 billion or 24.8 percent over the $ 11.873 billion actually spent in fiscal 1981. General funds revised In the crucial general funds, Thompson's revised budget was 8.3 percent above his request the year before, 6 percent above actual appropriations for fiscal 1981, but only 1 percent above actual spending for fiscal 1981 (See "Thompson cuts budget in a sea of Recession," June 1981, p. 24.) By midsummer, when the legislature adjourned its spring session, the General Assembly had passed appropriations bills that totaled $14.670 billion, including $8,302 billion in general funds. That was $151 million under budget a record of sorts; never in recent memory had the legislature appropriated less, overall, than the governor asked for. During the first four years of the Thompson administration, the General Assembly went over his budget by an average of $873 million a year, ranging from a low of $314 million over budget in fiscal 1981 to a high of $1,361 billion over in fiscal 1980. (See "The state of the State," September 1981, p. 2.) In the general funds, however, the General Assembly had gone over the budget by $38 million for fiscal 1982 These so-called "add-ons" approved by the Republican-controlled House and the Democratic-controlled Senate included $24 million for elementary and secondary education, $6 million for corrections and $5 million for mental health. In each of these cases, however, the appropriations were spread over a number of line items in the agency budgets; they were not committed to specific programs as lump sums. 30/March 1982/Illinois Issues

By late July, however, again citing the recession and Reaganomics, the govenor in effect re-revised the budget with his vetoes. Via line item or reduction veto, he cut $381 million overall, including $243 million in general funds. (In reappropriations for capital projects, he vetoed another $54 Billion, including $2.9 million in general funds.) As signed by the governor, appropriations bills totaled $14,235 billion, including $8,056 billion in general funds. His vetoes set another record, since appropriations after his cuts were $242 million less than appropriations the preceding year. No one can remember a governor who cut appropriations for one year below what he'd signed the preceding year. (See "The state of the state," September 1981, p. 2.) But the governor did not cut general funds appropriations below last year's level he allowed an increase of $294 million more than fiscal 1981. (Despite the record the legislature set for coming in under budget overall, the $ 381 million the governor vetoed was about average. During the first four years of his administration, Thompson vetoed an average of $387 million a year, ranging from a low of $88 million in fiscal 1981 to a high of $969 million in fiscal 1979.) Largest fund vetoed The largest and theoretically the most controversial of the fiscal 1982 vetoes was the reduction Thompson made in the state's appropriation, as employer contribution, to its five public employee pension funds: $183 million, including $171 million in general funds. By pension fund, the breakdown was $114 million from teachers, $37 million from executive branch state employees, $27 million from professors, $4 million from judges and $1 million from legislators. Thompson said he cut the pension appropriations for fiscal 1982 and only for fiscal 1982, he said because annual income was running significantly ahead of annual expenditures, resulting in a significant rise in the ratio of year-end assets to year-end liabilities, the so-called "degree of funding." The figures clearly showed that annual income was so far ahead of annual expenditures that Thompson could have eliminated, not reduced, the state's appropriation without threatening the pensions of those already retired at least for one year. And this was one reason why no one in the systems opposed Thompson's reduction. But another, and far more important reason, was that fiscal 1982 pay raises for all state employees depended in large part on the revenue the state would save by cutting back on pension spending; it was clearly a choice of pay raises now or pensions later. Nevertheless state employees, including legislators, served notice that if the governor reduced pension appropriations for fiscal 1983, they would oppose him and oppose him vehemently. The reduction in the state appropriations for pensions was the only significant large veto this year. But Thompson did cut the budgets for two of the three so-called "big spenders." He cut elementary and secondary education by $24.9 million, almost all in general funds and chiefly a reduction in special education. And he cut higher education by $7.4 million, again almost all in general funds and mainly in state student financial aid. March 1982/Illinois Issues/31 In practice, however, it was the smaller reductions Thompson made in public aid and other social services that became the most controversial of the fiscal 1982 vetoes. Thompson cut a total of $47.3 million, including $36.5 million in general funds, from the budgets of key social services agencies: $17.2 million from mental health, $15 million from children and family services, $13.3 million from public aid and $1.9 million from public health. It was Thompson's veto of $13.7 million from day care and other critical social services that the opposition Democrats, led by House Minority Leader Michael Madigan, sought to override: $4.1 million in day care, $1.3 million in foster care, $972,000 in institutional care, $1.1 million in other kinds of child care, $7.9 million in local initiative funds (the 75 percent state "match" for local social service agencies), $1.2 million in mental health and $380,000 in public health. (See "The state of the State," November 1981, p. 4, and December 1981, p. 4.) At the eleventh hour, under pressure from a coalition of local public and private agencies which provide social services under state contracts, Thompson compromised to avoid the political embarrassment of an override. He restored $4.6 million of the $13.7 million targeted for an override ($1.3 million for day care and $3.3 million for the local initiative). The only controversial social services veto actually overridden was the $972,000 in institutional child care. (See "Legislative Action," January 1982, p. 28.) Final adjustments By late October, when the legislature adjourned for 1981, the record shows the House and Senate had overriden only $3,041 million of the $381 million Thompson had vetoed (including $2,042 million of the $243 million vetoed in general funds). But that hardly set an override record since the General Assembly had failed to override a single dollar of Thompson's vetoes the year before. Thompson did veto one substantive bill that had to do with money matters, S.B. 181, sponsored by Sen. John Maitland (R., Bloomington), which increased state reimbursement to nursing homes for Medicaid patients. The bill would have increased maximum reimbursement for nonnursing services effective January 1, 1982; the cost to the state was estimated at $20 million a year. And there was considerable support among legislators, not to speak of nursing home administrators, for an override. But as was the case with social services, Thompson eventually compromised, agreeing to an increase that would cost the state only $10 million a year. (See "The state of the State," December 1981, p. 4.) Still, the compromise probably won't affect the appropriations picture. Since the Department of Public Aid did not request a supplemental appropriation, the cost of the increase in nursing home reimbursement is expected to be absorbed, via interfund transfers. During the fall session, however, the legislature did vote supplemental appropriations at Thompson's request totaling $95 million, including $7.3 million in general funds. The bulk of these supplemental was $70 million in federal block grant funds. Of the general funds, about half or $3.4 million went to the Department of Revenue for 175 new jobs required by changes in the tax laws that were adopted in the spring session. Other supplemental included: $1 million to the Court of Claims for claims awarded during the second half of fiscal 1981;

The general funds portion of the supplemental appropriations also included the day care funds Thompson restored under the social services compromise Thompson approved the supplemental appropriations with one exception: he vetoed $406,000 in general funds that would have gone to the Department of Revenue because the proposed program to allow an income tax checkoff for nongame wildlife preservation did not become law. At this writing, January 20, there were no supplemental appropriations pending before the legislature, nor were any expected to be introduced The new round starts March 3 for the fiscal 1983 appropriations process when Gov. Thompson presents his budget for the new year. Salaries for state's attorneys despite the 'unveto' REMEMBER the story of the unvetoed Well here's the last chapter. By law, the state must pay two-thirds of the salaries of county state's attorneys and the counties must pay the other one-third-but no more. (Remember that; evidently everyone else forgot.) Thompson, in revising his budget in April, eliminated the state's share from his appropriation recommendations about $3 million. Senate Democrats well aware of the state's need to economize, but arguing against the counties' burden in picking up this cost engineered passage of a compromise which reduced the line item for the states share of these salaries from 100 percent of itstwo- thirds share to 80 percent; total cost about $2.6 million. Thompson, in reviewing all bills approved by the General Assembly, eliminated the line item entirely when he signed the appropriation bill But the reaction was so strong from the counties that he decided to "unveto" the veto in what many observers feel was an unprecedented move. (The governor had filed the signed bill with the secretary of state before he changed his mind, so he asked the secretary of state to return the bill so he could erase his line item veto. The state Constitution doesn't say he can't change his mind on a veto. The Constitution only says that he has 60 days to take action on a bill or the bill becomes law.) But, what Thompson and the Senate Democrats had neglected to do was to amend the existing statute, which set the funding formula. In spite of the budget cut, the compromise, the veto and the unveto, the formula still stands. The state must pay two-thirds of the salaries hence, the need for the $650,000 supplemental to fund 100 percent of the state's share. 32/March 1982/Illinois Issues |