|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

The Illinois Issues Humanities Essays (second series)  An Essay on Language and Liberal Education By GARRY WILLS  This second series of humanities essays is made possible in part by a grant from the Illinois Humanities Council, in cooperation with the National Endowment for the Humanities. This is the second of five original essays by distinguished humanists to be published in Illinois Issues in 1982. No restrictions in regard to style, form or perspective have been placed on the authors. They have been encouraged to use any one of a number of approaches including exposition, analysis, satire and parody. Reprints of these essays are available at no cost from the Illinois Humanities Council, 201 W. Springfield, Champaign, Ill. 61820. July 1982 | Illinois Issues | 11 By GARRY WILLS

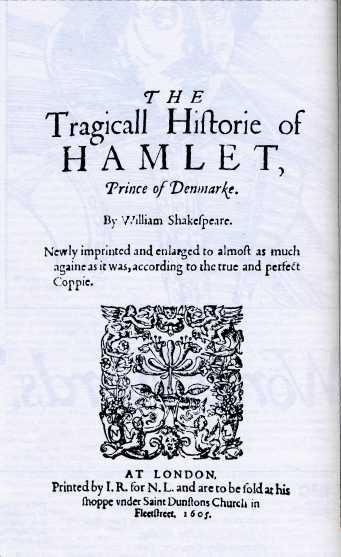

Actions speak louder than words, we are told; so that people bemused by words are somehow suspect, as if that were enough to detach them from reality. Hamlet is sometimes thought to be ineffectual because he is caught up in an internal debate which makes him "unpack my heart with words" and lose the very name of action. Indeed, when Polonius asks Hamlet what he is reading, he chants back in his "crazy" sing-song, "Words, words, words." The useful studies, we are sometimes inclined to believe, deal with things, not words. The "soft" studies are verbal — literature, the humanities, the liberal arts. According to Cardinal Newman:

The scientist can isolate, measure, and manipulate things to understand them, to predict their behavior, to put them at our service. In a practical culture such as ours, this seems the proper work of mankind. Why just describe, when you can do? Why care about phraseology, when you can get results? What's in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet. The smell is a thing — just ask a chemist. But do actions really "speak" louder than words? The very maxim is a play on words. We can only make actions speak by a metaphor. Hamlet says, "Murder, though it have no tongue, will speak with most miraculous organ." Maybe so. But the thing — mere ravaging of flesh — becomes murder only when intention is formulated. Take an objective fact, so called: Knife enters living human flesh. Already we are assuming some complex and verbally constructed concepts, like "living," like "human." But let us 12 | July 1982 | Illinois Issues

pretend that we have stated bald fact. What are we to make of it? What does that act mean at the most vital (or mortal) level? Was the knifing surgery, dissection, abortion, medical experiment, accident, suicide, murder, self-defense, defense of others, revenge, execution? If it was self-defense, we have to presume an articulated concept of the self, which is an endless — and a verbal — labor. The mere fact as mechanical act does not speak at all. Only the agents speak, under cross-examination, words uncovering the reality these people are. Hamlet, we might say, was properly flippant about words (words, words). What, after all, is he but the collocation of certain words by Shakespeare? But what, for that matter, are we but verbal collocations? I look about me and find spaces of mainly pinkish and brownish light called faces. How do I know that, masked by such pleasant blotches, there are other minds at work? I cannot see you think, much less see your thought. How do I know that I am looking at the priestly mask of that thing we call a person? Some philosophers tell us we recognize each other, in this pleasant world of colored blotches, only by "the analogy of other minds." David Hume, for instance, said we separate animals from the rest of the universe by comparing their acts with ours: "When therefore we see other creatures, in millions of instances, perform like actions and direct them to like ends, all our principles of reason and probability carry us with an invincible force to believe the existence of a like cause" (Treatise 1.3.16). But John Locke had argued that we make a further discrimination, separating humans off from animals, by refining the analogy: "That there are minds and thinking beings in other men, as well as in himself, every man has a reason, from their words and actions, to be satisfied" {Essay 4.3.27, italics added). You act, react, like me — so you must, in some measure, be like me. How do I gauge your actions, reactions? Mainly by your verbal responsiveness. Unlike my dog, you report yourself out to me. You tell me what is on your mind. We are all foreign correspondents from that heart of darkness where a living self is stranded, sending signals like the Count of Monte Cristo, hoping the prisoner of another cell, another body, will signal back. And our main signal is the word, the original telegraphy, approximating (for its intimate revelations) telepathy. Talk to a judge who has been forced to deal with a deaf-mute defendant and you will see how vitally we depend on words to reach, judge, support, punish, or reward each other. Through words, minds distant in time as well as space are revealed to us. Plato lives as a teacher long after his own teacher, Socrates, has died — he lives in the pupil's words. We learn not only this or that proposition from Plato's dialogues, but the way his mind worked. Words "selve" their speaker, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, "Myself they speak and tell," no matter what else their message is. The American philosopher, C. S. Pierce, could even say, "My language is the sum total of myself." A highly developed mind not only reveals itself, but develops itself, through the subtleties of language. To quote Newman's Idea again:

We hear in Hamlet that "there has been much throwing about of brains" in a controversy. We are always throwing our brains about, filling the air with the very motions of our spirit once words have escaped what Homer calls the barriers of our teeth. Or, to use a different metaphor, we are engaged in continual brain surgery on each other, using instruments finer than the best-edged scalpels, more penetrating than laser beams. Words get through where all else fails. Men and women live on in their words because they always lived in words. The very freightage of words with the self of their speaker explains the difficulty of translating eloquent language. Newman once more:

The mixing of self with the expression of that self makes works of genius irreplaceable, and led Milton to revere the great books almost as much as he did the great minds that produced them:

July 1982 | Illinois Issues | 13

John Ruskin, too, marveled at the way words keep great minds present to us:

We may, by good fortune, obtain a glimpse of a great poet, and hear the sound of his voice; or put a question to a man of science, and be answered good-humoured/y. We may intrude ten minutes' talk on a cabinet minister, answered probably with words worse than silence, being deceptive; or snatch, once or twice in our lives, the privilege of throwing a bouquet in the path of a princess, or arresting the kind glance of a queen. And yet these momentary chances we covet; and spend our years, and passions, and powers, in pursuit of little more than these; while, meantime, there is a society continually open to us, of people who will talk to us as long as we like, whatever our rank or occupation; — talk to us in the best words they can choose, and of the things nearest their hearts. And this society, because it is so numerous and so gentle, and can be kept waiting round us all day long — kings and statesmen lingering patiently, not to grant audience, but to gain it — in those plainly furnished and narrow ante-rooms, our bookcase shelves — we make no account of that company, perhaps never listen to a word they would say, all day long (King's Treasuries). Words not only reflect their user's self. They almost have a self of their own; shift countenances, as it were, smile or frown, when they keep different company. To understand them, we must trace what Ruskin called their genealogy, "all their ancestry, their intermarriages, distant relationships." What a word is doing depends on what other words it is doing it with (and what they are doing). Hamlet, at his own death, tells Horatio, "Absent thee from felicity awhile." Brute paraphrase can give the basic message, "Don't die yet," though the original, irreplaceable words say a good deal more. What is Hamlet saying, beyond the paraphrase? Well, for one thing, he is praying, as we see from the formal inversion (absent thee), the Latinity (absens, felicitas), the formal personal pronoun (thee). This stately little dance of Latin words is followed by a sentencing to life, expressed in hard and aspirated monosyllables: "and in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain — to tell my story." Hamlet is just a bunch of words neatly put together; but the choice of words keeps telling us who and what he "is" as we try to puzzle out who and

Up from my cabin, Why do we read Hamlet? Young writers are often told they must write only from their own experience, "authentically," from what they have actually lived and seen. They should not take, at second hand, from literature, what they can get first hand from life, hot and raw, to put on the page. But why put it on the page at all? 14 | July 1982 | Illinois Issues

It will be totally useless there if others must refuse to get things from a mere book, must go out on their own to take things direct from life. Actually, literature comes from literature, which is life. Most people live from an unexamined and trashy literature all around them, stories and slogans and maxims shaping their expectations and values, "thinking by infection," as Ruskin put it, "catching an opinion like a cold." Literary study just disciplines an activity we all engage in all the time, examines the words all around us. Shakespeare, so far as we know, did not have the experience of being a murderer or a woman. He never saw Greece or Rome, Venice or Verona. No matter — he had Plutarch; he had the Italian novellas. He had words. Hamlet's mind is all "made up." Yet we only know other minds as words make them up to us. We invent our world verbally, discover others through a scanning device inescapably verbal. Why read Hamlet? To experience life at a level below the trashy surface of the other stories we tell ourselves every day. To shape human response on a larger scale. Science gives us things that are useful. But useful for what? Given television, what will we show on it? Given communications equipment, what will we communicate? Even a philosopher called "utilitarian," even David Hume, said that reason gives us means to ends, but that ends are only given us by man's evaluative instruments (for him, the moral sense): "Usefulness is agreeable and engages our approbation. This is a matter of fact confirmed by daily observation. But useful? For what? For somebody's interest surely. Whose interest then?" And what is anybody's real interest? Those are questions no mechanical equipment can ever give us. Science can get us to many places. It cannot tell us where we ought to go. If going becomes its own excuse, then means have eclipsed the end of human life. That is one reason we read Hamlet. Also, of course, for fun. Like everyone who loves words, Shakespeare liked to play with them, though his can be deadly play. Some people affect to think puns a mental aberration; but he knew how words are always turning on one, showing a tricky other side to our mind. That is why Shakespeare could fashion some of his greatest speeches from a pyrotechnical shower of puns. Give him, for instance, a group of musical

Poor Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern did not really listen to those puns. If they had, they would have known they were in far over their depth; they would have cleared out, and lived. How many of our daily misunderstandings have turned on a light word taken amiss, or a warning not weighed heavily enough? If someone has not caught the drift of our words, we say "You misunderstand me." If a person shows sterling integrity, we say he is as good as his word. Hilaire Belloc wrote an ironic poem, "The Fanatic," on the meaning of "giving one's word." Part of it goes:

We all live invisibly meshed in words. Not only do our minds mingle in them, but words almost seem to July 1982 | Illinois Issues | 15 breathe with our bodies — so much so that some poets walk or gesture while composing their lines, sounding the music on their own body's instrument. Thoreau said that when we look at a painting, we see an artifact outside us. But when we read a poem to ourselves, we shape an artifact of our own breath, carve it with our tongue. And this shaped thing reaches others in its entirety. St. Augustine dwelt on that wonder in one of his sermons:

Enough, then, of the scorn for merely verbal distinctions, for "nothing but semantics" — as if the very word for meaning had no meaning. The folk wisdom on this matter is mainly folk nonsense. Actions "speak" louder than words only when they back up words, when they serve a meaning we could not reach but for verbal instruments. A rose by any other name might smell as sweet, but it would not sound the same — in Shakespeare's line, to begin with; say "A peony by any other name," and you have pinched the vision. The name may once have been arbitrary; but now it comes to us savory with a thousand memories of our own and others' use of the sound and symbol, beginning with Homer's 'rhodo-daktylos" Dawn. Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words will never hurt me? Palpable nonsense. We all learn, indecently early, the words that can break friendships, wound hearts, end worlds — words like kike and spick and nigger and whore and fag. We can reach with words through another person's shield of privacy and dignity. More important, we can withhold a word of love or understanding, blight another's life precisely because that life was close to ours, dependent on our words. How we address each other is so important that Edmund Burke thought the very words for good and evil came to us with emotional impact derived from the way our parents or teachers first uttered them to us. I have seen, we all have, words almost visibly reanimate the despondent, seen words strike down the confident. And we have all had words fail us at important moments. When we feel we cannot reach another person, we lament, "I do not know what to say." Most of us do not know what to say, about most things; and that hedges us in as human beings. That is why we go to those who do know, who can expand our world of words, which is our world. The ultimately useful study directs us toward the mysteries we deal with, and the mysteries we are: words, words, words. The author: Garry Wills  Garry Wills, professor of history at Northwestern University, has written a number of books on American politics and culture, including the recently published The Kennedy Imprisonment: A Meditation on Power. Some of his other works include the following: Chesterton: Man and Mask (1961); Bare Ruined Choirs: Doubt, Prophecy and Radical Religion (1972); Confessions of a Conservative (1979); and Explaining America: The Federalist (1981). 16 | July 1982 | Illinois Issues |

|

|