|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

CHAPTER II The 1970 Constitutional Convention: The beginning of the end

The voters of Illinois approved the call for a constitutional convention by an impressive 600,000 vote plurality. The victory for "Con-Con" in the November 1968 election was a tribute to the well-organized "good government" campaign conducted by bipartisan state officials, business and citizens groups, and the media. But, as noted by Con-Con President Samuel W. Witwer, The 1870 constitution was in itself perhaps the strongest force behind voter approval. . . . Nearly a century of experience provided one clear and simple conclusion — that a new constitution was needed desperately. The old one was too rigid and detailed. The state was forced increasingly to seek ways around its unworkable Constitution which became a system of evasions, circumventions, and at times downright violations of clear mandates of the basic law.1 On December 8, 1969, the Sixth Illiniois Constitutional Convention opened with much official fanfare (see "Forming the 1970 Con-Con" on p. 10 for detailed description of the convention call). When the convention finally concluded its work on September 3, 1970, it had altered the proposed document enough to permit the eventual elimination of cumulative voting. Cumulative voting issue When the Constitution Study Commission recommended that the question of calling a convention be placed before the voters, it did not recommend any constitutional changes. Instead it offered what it called a "round up" of problems. Accordingly, minority representation received one line: "Does Illinois' unique system of cumulative voting presently fulfill the functions for which it was designed?"2 The minimal attention to the issue certainly did not indicate how important it would become at the convention. In preparing background materials for the 1970 Constitutional Convention, Professor David Kenney, then a political scientist at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, was chosen to write the paper on representation in the General Assembly. Kenney reviewed the usual arguments for and against cumulative voting and added that it "tends to confuse the voter." He concluded Illinois Issues Special Report | 9

"The election of three legislators at large from each representative district has the effect of preventing the representation of diverse minority interests such as might occur if the same total number of representatives were chosen from single member districts. . ."3 The issue of cumulative voting was hotly debated at the convention and the delegates were faced with several choices. An account of the debate on the cumulative voting provision during its three readings on the floor of Con-Con provides a fascinating picture of the personalities and turmoil of the convention.4 On July 14, 1970, the legislative committee's majority proposal calling for the retention of multi-member districts and cumulative voting, was presented for first reading debate. The partisan factions which emerged during the debate remained in place for the duration of the convention and are worth examining. For partisan reasons the Chicago Democrats favored the existing system of cumulative voting from three member districts. (They did not, however, like its use in the primary — a system which was seen as a threat to party organization). Independents from the Chicago area and downstate favored cumulative voting because it allowed them the possibility of unseating a party regular through the use of the "bullet" vote (see "The bullet vote" on p. 11). Although they held similar positions on cumulative voting, the Democrats and independents were unable to work together for its passage during the next several weeks because of bitter opposition to each other on the previously debated judicial selection issue (Democrats favored elected judges; independents wanted a merit selection process). The Republicans sought the abolition of cumulative voting and the establishment of single member districts. They argued that cumulative voting was confusing to voters and permitted party collusion in choosing candidates for elections. Behind their position was the belief that single member districts would allow more Republicans to be elected to the House, as was the case in the Senate. On first reading debate, the Republicans were able to capitalize on the split between the Democrats and independents 10 | Illinois Issues Special Report

and substitute their desired single member district plan. After they had extracted a promise from the Republican leaders to work for a separate submission to allow voters the option of retaining cumulative voting and three member districts, approximately 15 independents joined the Republicans. On July 17, 1970, the delegates voted 53 to 37 to substitute a minority report of the legislative committee which favored single member districts, and thereby abolished the cumulative voting provision suggested by the committee's majority. On second reading (August 13), the coalition of independents and Republicans was able to reject an attempt by the Democrats and some downstaters to put cumulative voting and multi-member districts back into the main body of the proposed constitution. The vote was 52-56 not to change the first reading proposal. But the convention leaders, keeping their first reading promise, did help adopt the plan of separately submitting the multi-member, cumulative voting provision to the voters. This action provided a unique contrast to the separate submission agreed upon for judicial selection. Consequently at this stage the convention had decided to leave the judicial status quo in the main document and separately submit the appointive plan and to place a new, single-member district plan in the body of the constitution while submitting the legislative status quo separately. Although the Daley Democrats had scored a major victory in the judicial debate and now had their multi-member district plan as an alternative, they remained less than happy about the turn of events. It would have been much easier for Democratic precinct captains in Chicago to instruct the voters to vote "yes" on the main document and "no" (or abstain) on the separate issues. Second reading decisions by the convention had made the prospective ballot more confusing than they would have liked and had given a strategic advantage to single-member district advocates.5 (It should be noted that the majority report's provision was amended on second reading to prohibit the parties from limiting their nominations for House seats to less than two for each district, and this amendment ultimately became part of the 1970 Constitution.) Con-Con President Samuel W. Wit-wer was concerned that the two confusing separate submissions would doom the passage of the entire constitution. The day before third reading, therefore, he appeared before the Committee on Style, Drafting and Submission to suggest that both alternatives for the judicial and legislative articles be placed outside the constitutional package as amendments to the 1870 Constitution or the new constitution, should it be approved. Although this plan was not recommended to the convention by the committee, it eventually became the proposal adopted by the delegates in complicated and confusing final action of the convention. On August 28, through some efficient parliamentary maneuvering and surprising downstate support, the Cook County Democrats were able to put the cumulative voting, multi-member district provision back into the main body of the new proposed constitution. The vote on the provision, which included the placement of the question of single member districts on the ballot as a separate item, was 60-41. After this vote was taken, something curious happened. Because the delegates were anxious to leave for a night of convention-farewell partying, the Chicago Democrats, and particularly legislative committee chairman George Lewis, neglected to ask for approval of the entire legislative article and its Illinois Issues Special Report | 11 automatic submission to the style committee for final enrollment in the proposed constitution. The next morning when Lewis made this routine proposal, he was startled by the vote: 53 "yes," 24 "no," and 23 abstentions. Because the legislative article lacked the 59 voters needed for approval, it was technically still debatable. "It was a vote which stunned the convention. As one looked over the roll call, the most glaring factor which stood out was the absence of seven Chicago Democrats, including their floor leader, Thomas Lyons. Apparently these delegates had celebrated far into the morning and had simply overslept, thus missing the crucial roll call vote "6

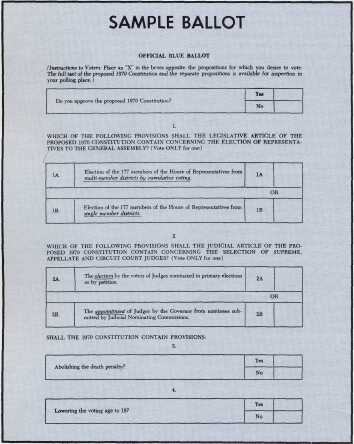

During the preceding 24 hours, a coalition of Republicans and independents, unhappy with the unfavorable ballot positions of both the judicial and legislative articles, had formed under the leadership of merit selection proponent Jeffrey Ladd and had embraced the Witwer proposal. They favored deleting both alternatives for cumulative voting and judicial selection and placing them separately on the ballot for voter judgment. Delegate Wayne Whalen, representing this coalition, moved that the rules be suspended for reconsideration of amendments to both the judicial and legislative articles. A convention observer describes the scene thus: The convention exploded. Turmoil, chaos, and confusion raged. [Paul] Elward, master parliamentary strategist, assumed floor command for the Chicago Democrats. Challenging Whalen's motion as improper under convention rules, raising points of order, appealing adverse rulings of the chair, employing every procedural tactic within his vast experience, Elward, ably assisted by Arthur Lennon, [Harold] Nudelman, and Mrs. [Helen] Kinney fought furiously, relentlessly, to avert the disaster implicit in the motion. The battle raged through the morning hours and the normal lunch recess. When finally the Whalen motion was put, every challenge having been withstood, it passed in two key roll calls, sixty-eight to thirty-nine and sixty-two to forty-six, respectively. The rules were suspended.7 During the next seven hours of acrimonious debate, the coalition outlasted all challengers. At 9:15 p.m. on August 29, 1970, the amendment to delete both judicial and legislative alternatives was adopted 70-39. Although the separate submission plan was again attacked on subsequent days, it remained on the final ballot form when the convention adjourned on September 3. On December 15, 1970, Illinois voters approved the new constitution, 1,122,425 to 838,168. On the separate questions on the ballot, voters approved Proposition 1A, providing for multi-member districts with cumulative voting, and Proposition 2A, providing for election of judges, thus retaining provisions of the 1870 Constitution (see sample ballot at left). The vote favoring multi-member districts and cumulative voting was 1,031,241 to 794,909. Not surprisingly, support for cumulative voting was especially heavy in Chicago. Initiative provision One of the provisions of the 1970 Constitution is a constitutional initiative process restricted to changes in the legislative article relating to structure and process. "In recognition of the fact that the General Assembly might not choose to submit amendments affecting its own procedures or structure . . . the 1970 constitution also provided for the first time that amendments to the legislative article could be proposed to the voters by petition. . ."8 As dissenting Chief Justice Joseph Goldenhersh later explained in Coalition for Political Honesty v. State Board of Elections: 12 | Illinois Issues Special Report

At the time of the constitutional convention only 13 state constitutions contained provisions for an initiative (7 Record of Proceedings, Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention 2299). The [Illinois] Constitution of 1870 contained no such provision, and constitutional amendment could be commenced only by constitutional convention or legislative proposal. (Ill. Const. 1870, art. XIV, sec. 1, 2.) It is apparent from the constitutional debates that the framers of the 1970 Constitution were acutely aware of the abuse of the initiatives in other states and wished to prevent its misuse in Illinois. The discussions show a clear intent to limit the use set forth in article XIV, Section 3, and to that end the convention included the requirement that the petitions be signed by 8% of the vote cast in the preceding gubernatorial election. . . (emphasis added).9 Although the 1970 Constitutional Convention rejected a general amendment process for the citizen initiative, it was willing to consider one limited to the legislative article, which was proposed by the legislative committee. On July 15, 1970, delegate Louis Perona presented the committee's majority position. He argued that the restriction to the legislature was needed "because of the vested interest of the legislature in its own makeup." He said, "We feel that it's unlikely that the legislature would propose an amendment reducing the number of legislators or in flanging from cumulative voting as we have today to single member districts. I'm not saying whether these issues might be better or not, but I'm saying that they're not likely to present these issues to the voter."10 This remark proved to be

Delegate Mary Pappas, as spokesperson for the committee's minority report, argued against the initiative provision. "Repeated abuses have been documented in the use of the initiative. . . . Groups in opposition to a Constitutional Convention or to any other legislative-initiated amendment to the Constitution or to any legislation implementing the legislative article can use the initiative to place conflicting issues on the ballot, thus causing further confusion for the voter and playing havoc with the legislative process, the referendum process, and the legal status of the amendments in question at the same time." She further stated that the legislature had proposed changes in its structure and process over the years, and that there was no reason to believe that the legislature would not act if the voters made known their desires.11 Although they had decided that the initiative would be limited to structural and procedural matters, the delegates were concerned with the precise definition of matters which would be subject to initiative under the proposal. Delegates wanted to know if the proposed initiatives would cover matters such as cumulative voting and the size of the legislative body. Delegate Perona stated that the committee intended that those things be included. But then delegate Dawn Clark Netsch questioned Perona concerning a clarification that would become significant a decade later. MRS. NETSCH: Then whatever agency is created by law with the authority to test those, it would be limited to the technical requirements; and would that, then, mean that an inquiry into whether or not the proposed amendment was within the subject matter of the constitutional initiative, that is, one dealing with structural and procedural requirements, would be determinable, if at all, only by the courts? It could not be determined by an election agency. Is that correct? The proposal for the article on the legislative initiative was adopted on third reading for final passage and enrollment by a 103-0 vote on September 1, 1970. An analysis written shortly after the adoption of the new Constitution by Charles Dunn, counsel to the convention's legislative committee, suggested that many of the issues concerning the legislature had been deferred rather than decided. Dunn asserted that the "structural and procedural matters of deepest concern to the legislature were hardly changed in the 1970 Illinois Constitution."13 But the new Constitution did allow for initiatives which would permit constitutional amendments other than by legislative action. The decade of the 1970s saw several attempts to use this initiative power. Illinois Issues Special Report | 13 |

||||||||||||

|

|