|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

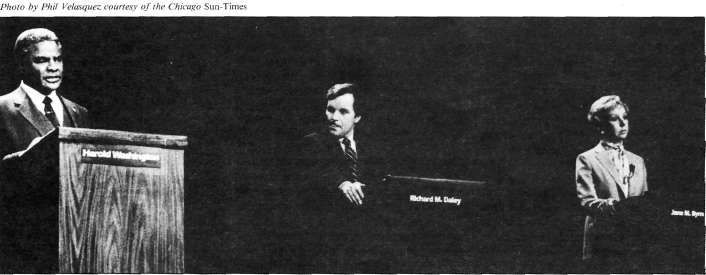

EXCERPTS from the latest book on Chicago politics The making of the mayor: Chicago, 1983 THE NEWEST book on Chicago politics is The Making of the Mayor: Chicago, 1983, co-edited by Paul M. Green and Melvin G. Holli and published last month by Eerdmans of Grand Rapids, Mich. The book looks at last year's mayoral primary and general election from every angle. It is at times a narrative, at others a detailed analytical work. The several authors write about the candidates, the politics, the campaigns, the campaign coverage and the outcome. Some chapters go back in time to provide context for the events and candidates of 1983; others look ahead to Chicago's future politics. The book's eight chapters begin appropriately with Robert McClory's "Up from Obscurity: Harold Washington" and end with William Grimshaw's "Is Chicago Ready for Reform?" Sandwiched between are chapters dealing with the events of the 1983 campaigns and elections — with a different focus from each author. Green analyzes the campaigns and the election itself; Michael Preston focuses on the resurgence of black voting; Doris Graber provides detailed research on media coverage with her own conclusions; Richard Day critiques the polls; and Don Rose details episodes as only an insider can. Milton Rakove, in his last major writing effort before his death, reflects on some of the effects the election could have on the machine. The idea for the book was conceived in early 1982 as the editors planned a post-election conference of the same title to be held on May 20, 1983. Many of the chapters were first presented at that time. The book is clothbound, priced at $13.95 and includes an introduction by the editors. Excerpted here are four of the chapters: Grimshaw evaluating reform possibilities, Rose detailing the candidates' moves, Day considering the effects of polling and Graber presenting her research and findings about the media's role in covering the issues and candidates. The challenge of "fairness" in reform politics Machine politics revolves around power. Benefits are distributed to those who are deemed worthy by the machine, and they are withheld from the unworthy — those who have voted "wrong." Machine politics amounts to an exchange relationship: benefits for votes. The model for machine politics is the club: those in the club benefit, while those who are not, lose out. Reform politics, on the other hand, revolves around efficiency. The goal here is not to reward friends and punish enemies; rather, it is to attain high cost-benefit ratios. Benefits are dispensed, then, in the most rational, cost-effective manner. The model for reform politics is the business corporation. The third alternative, which is being expressed by blacks, revolves around neither power nor efficiency. The objective is fairness. Thus, equity displaces power and efficiency as the basic principle of distribution. The model for the new black politics is the church. . . . The church has been the primary value-nurturing institution of blacks. Its moral teachings concerning fairness and brotherhood provide a radically different basis for political action. The new black politics uses need, rather than the machine's principle of reciprocity or the reformers' cost-benefit calculations, to establish a system of benefit distribution that is designed to achieve equity. Given the white and middle-class bias of the prevailing distribution system, the new arrangement cuts sharply against the grain, and it entails an acute downward redistribution of benefits. For this reason, the new black politics may best be understood as a lower-class reform style of politics. * * * * * Voting returns bear out the existence of a sharp black class divide. South of 63rd Street, in the higher-income black wards, the support for reform has been strong. Virtually every one of these wards has at some point put a reform-minded alderman into office. These are also the wards that gave Mayor Washington the most support. It is a different story north of 63rd Street and on the impoverished West Side. Reform has picked up little help in these areas. The principal exception is the strong support they gave Harold Washington. If the new mayor is to turn the exception into the rule, he must demonstrate that the ethic of fairness is preferable in the long run to the more obvious short-term enticements of the ethic of power. 18/June 1984/Illinois Issues  Harold Washington delivers his opening statement during the first debate of the Democratic primary campaign. Challengers Richard M. Daley and Jane M. Byrne wait to respond. Besides the racial conflict and class problems, Mayor Washington faces an integration problem involving the black middle class. The ethic of fairness supported by the black middle class developed to some extent because of their exclusion from the white corporate opportunity structure. As these barriers are increasingly set aside and knocked down, the blacks who enter the corporate world will acquire greater exposure to the ethic of efficiency and economy. As a result, they may begin to vote their pocketbooks instead of their hearts. Thus the ethic of fairness sits squarely between the ethic of power and the ethic of efficiency, and blacks are being pulled away from the center in both directions. Mayor Harold Washington's task is to fortify the middle ground. It is a challenge as formidable as any faced by a Chicago mayor. It is equally significant. Equality and fair play are the ideals toward which our system of government is supposed to be directed. So, to the extent that Harold Washington is successful, he will have made a profound contribution to the improvement of life and politics in Chicago. William Grimshaw is a professor of political science at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. The race was about race There are those today, including this writer, who believe that Epton's frequent fulminations and explosions against the media and many of his former IVI-IPO-type supporters during the mayoral campaign stemmed from the fact that he had never before had to campaign so vigorously, subject himself to ongoing media scrutiny, or otherwise engage in the rough and tumble of Chicago politics. But it is almost certain that he would never have become a citywide candidate had the referendum creating single-member districts not unseated him from a sinecure. It was clear that he could never win his old seat back against a Democrat in a head-to-head contest — especially now that the district was more than 80 percent black. Thus Bernie Epton moved out of Hyde Park and to the Gold Coast of the near North Side. When he let it be known, then, that he was available for a draft to become the GOP standard-bearer in the 1983 mayoral election, the reaction in political circles was that this was his last hurrah, a kind of ego trip and another of his eccentric moves. According to those closest to him, Epton thought that he would be running against the Jane Byrne and Ed Vrdolyak machine and that he would lead a charge of IVI-IPO liberals, disaffected blacks, and reformers, along with the city's closet-bound Republicans. He hoped to fight the good fight. * * * * * Blacks had elected Jane Byrne in 1979. Now they had defeated her. . . . A write-in was the last resort, since Epton could not be talked off the ballot or bought off. ... So Byrne announced the write-in effort, which had been hinted at just after the primary, on March 15. Lunacy? Not in the context of Chicago's racial politics — and everyone understood that. Suddenly the write-in campaign was in the news-weeklies and the national press. Most of Byrne's primary campaign staff was against the idea, including campaign manager Bill Griffin. Few staffers other than aide Nancy Philippi and media hand Pat Fahey remained. Husband-advisor Jay McMullen also remained. Fund-raiser Thomas King, head of the Kennedy-family-owned Merchandise Mart, was on board, then off quickly upon orders from the Kennedy family. David Sawyer, the media wizard who had brought Byrne back from the political dead in November only to have her die again in February, was on board. Then the Democratic National Committee threatened to blacklist him as a consultant, and he jumped off. Multimillionaire real estate developer Miles Berger and his wife Sally, both beneficiaries of Byrne largesse during her tenure, stayed on. Neither the Kennedys nor the DNC wanted to be associated with a campaign that was outside the Democratic party and based on race. Byrne, you see, was developing her own code words. In her opening statement and in interviews and speeches she said she was mounting this near-impossible campaign because the city was still too "fragile" to be entrusted to anyone else. It could, she said, "go up" or "slip back.". . . June 1984/Illinois Issues/19

To mount a write-in campaign successfully, the Byrne campaign would have to undertake a massive education campaign, which was happening in the media already. They explained that one had to write in the name of the office on the little Vote-a-Matic envelope, then make a box and put in an X, and then, finally, the candidate's name. Stickers and rubber stamps could not be used; there was already case law against it. But perhaps the election board could be petitioned to preprint a place for write-ins. The board's answer was no. Then the circuit court said no again. A week after the announcement of the campaign, despite earlier protestations that she would carry on regardless of what the courts said, Jane Byrne threw in the towel. It was a hell of a week. Byrne said afterward that she was a Democrat: it was her way of saying that she was not backing Epton. It was also her way of saying she would do nothing for Washington. But then, neither would Daley, who had actually endorsed him formally. * * * * * Racial politics was nothing new to Ed Vrdolyak. He first won election as ward committeeman in 1968, running as an insurgent, by suing the city to prevent a school busing plan from touching his neighborhood. The East Side, where he came from and stayed, is a racially conservative, white ethnic enclave. Racial change there means more Croatians are coming in. . . . Vrdolyak's ability to retain peaceful control of the 10th Ward, with its white ethnics, blacks, and Mexicans living adjacent to each other in hostile camps, is testimony to his political skill. As party chairman, following a bruising battle he and Byrne waged against incumbent George Dunne, he was being applauded for almost getting Adlai Stevenson elected governor. His next big triumph was to be the renomination of Jane Byrne. Sensing that Byrne was slipping, Vrdolyak made a speech to party loyalists the weekend before the primary election, stating baldly that the race was about race. A vote for Daley would be a vote for Washington and against the way things were supposed to be, he said. A vote for Byrne was the only way to keep things right and white. Unfortunately for him, a few reporters whom he did not recognize were in the audience — one from the Chicago Tribune, one from the Kansas City Star, and a nationally syndicated columnist who appears in the Sun-Times. Some people credit and some blame the speech for Washington's victory. It surely didn't hurt his cause, though that may not be what actually killed off Daley. After the primary, Vrdolyak publicly gritted his teeth and endorsed Washington; but the endorsement, personal and later on behalf of the party, didn't mean much. . . . Don Rose is a long-time independent political consultant and media advisor. The Daley campaign that floundered The major polls showed the incredible volatility of the Chicago electorate and how the political fortunes of various candidates could rise and fall in shockingly short periods of time. Richard M. Daley came through most of 1982 riding a high wave of public esteem and promising bits of reform, or at least restoration, and to rescue his father's beloved city from the clutches of the "wicked bitch" of the Northwest. Jane Byrne, under the adroit professional grooming of media consultant David Sawyer, rose like a phoenix from the ashes of low public esteem to lead the polls until the eve of the primary election. Richard Daley's campaign and public esteem ratings stalled in neutral in December. Newspaper columnists and the Byrne camp derided Daley for not being able to speak his mind on the issues, and one popular columnist called him "chicken." This baiting worked, for Daley entered the debates and, to the pleasant surprise of his supporters, took the negative edge off the widespread rumor that he could not stand on his feet and debate at the same time. Speech lessons at Northwestern had undoubtedly improved his delivery; but they did not do much for his standing in the polls. As the public opinion polls showed, nothing seemed able to resuscitate Daley's floundering campaign, for he never improved his position from December 1982 onward. His endorsements by major newspapers may have nudged a few points his way, but not enough to win and only at Byrne's expense. Richard Day, chief executive officer of Richard Day and Associates, is a political pollster and media consultant. The role of the press . . . Most strikingly, Bernard Epton, the Republican contender, received barely any coverage at all during the primary. He was indeed "the invisible man," as he so bitterly complained. Although most political observers granted that all three Democratic hopefuls had a chance to win the primary, the alternatives represented by a Washington-Epton, Daley-Epton, and Byrne-Epton contest were hardly weighed in the media. If voter enlightenment was a goal, they certainly should have been. Had the three papers treated all candidates roughly equally, the percentage of coverage listed for each kind of theme should have ranged between 20 and 30 percent in the primaries. During the general election, the percentages allotted to Washington and Epton 20/June 1984/Illinois Issues should have been similar. Obviously, this was not the case. During the primary, the Tribune and Sun-Times gave a disproportionate amount of coverage to Jane Byrne, while the Defender dwelt largely on Washington. Byrne's policies and the ethics of her conduct received particularly heavy attention in the Tribune. The Tribune also focused heavily on Daley's personal qualifications but slighted questions about the ethics of his campaign. That such choices were idiosyncratic to each paper becomes clear when one compares coverage among the three papers. In the Sun-Times and Defender, for instance, there was a much better discussion balance between the policy stands of Byrne and Daley than was true in the Tribune. Similarly, neither the Sun-Times or the Defender dwelt disproportionately on Daley's personal qualifications. Nor were ethical concerns in the Daley campaign de-emphasized in these two papers. In fact, the Defender, unlike the other two papers, put the spotlight on ethics issues in the Daley campaign. The conclusions to be drawn from comparing coverage is that there was ample story material so that the media could have supplied the voters with balanced accounts in which comparable dimensions were sketched out for each candidate. A voter, eager to compare the policy positions or integrity of the candidates, for instance, would then have been able to find adequate information for all three on these scores. By and large, 1983 primary election news did not meet this need. The situation was similar during the general election campaign. Then all three papers devoted the lion's share of coverage to Washington. Epton received a mere 16 percent of exposure in the Defender, compared to 84 percent for Washington; in the Tribune, it was 30 percent for Epton, compared to 70 percent for Washington; the Sun-Times showed the best balance: it finished with 39 percent for Epton compared to 61 percent for Washington. However, when one looks at the distribution of coverage among various kinds of themes, the Sun-Times actually turns out to be less well-balanced than the other papers. For instance, it devoted 24 percent of Washington commentary to policy themes, compared to 17 percent for Epton. In the Tribune, Epton was ahead in coverage of policy themes with a score of 29 to 24 percent. There was a similar five percentage point spread in the Defender, but it went in the opposite direction: policy themes constituted 28 percent of the coverage for Washington but only 23 percent for Epton. Similar imbalances marked the other coverage areas, with papers differing in their choice of either Washington or Epton as the candidate deserving proportionately more attention for particular themes. Again, the obvious message is that choices made by journalists, rather than the nature of available news, made the difference. If journalists had desired more balanced coverage, they could have attained it. * * * * * During the Chicago campaign there were no ground rules for covering a potentially inflammatory contest. Rather, there was a great deal of uncertainty about the kinds of issues that candidates and reporters may legitimately raise without earning the "racism" label. While Harold Washington, for instance, acknowledged that it was appropriate to discuss his legal problems, others called it racism on the grounds that many white politicians in the past had escaped similar scrutiny of their legal problems. A great deal of controversy swirled around an advertisement urging people to vote for Bernard Epton "before it's too late." Epton's campaign managers denied that the commercial was playing on racial fears, but Washington supporters insisted that it did. There were no guidelines to determine whether the slogan was inappropriate. Questions also arose about the propriety of raising certain policy issues. For instance, was it racist fear-mongering when candidates and the media mentioned the issue of city housing policies when it entailed questions of locating poor black families in more affluent white neighborhoods? Should candidates and the media dwell on the race of public officials whose hiring or firing is discussed? Is it responsible for candidates to raise — and the media to publicize — the specter of racial hostilities in the wake of a hardfought, dirty campaign? Obviously, such questions reveal major dilemmas for which ground rules need to be worked out. Doris Graber is a professor of political science at the University of Illinois in Chicago. June 1984/Illinois Issues/21

|