|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

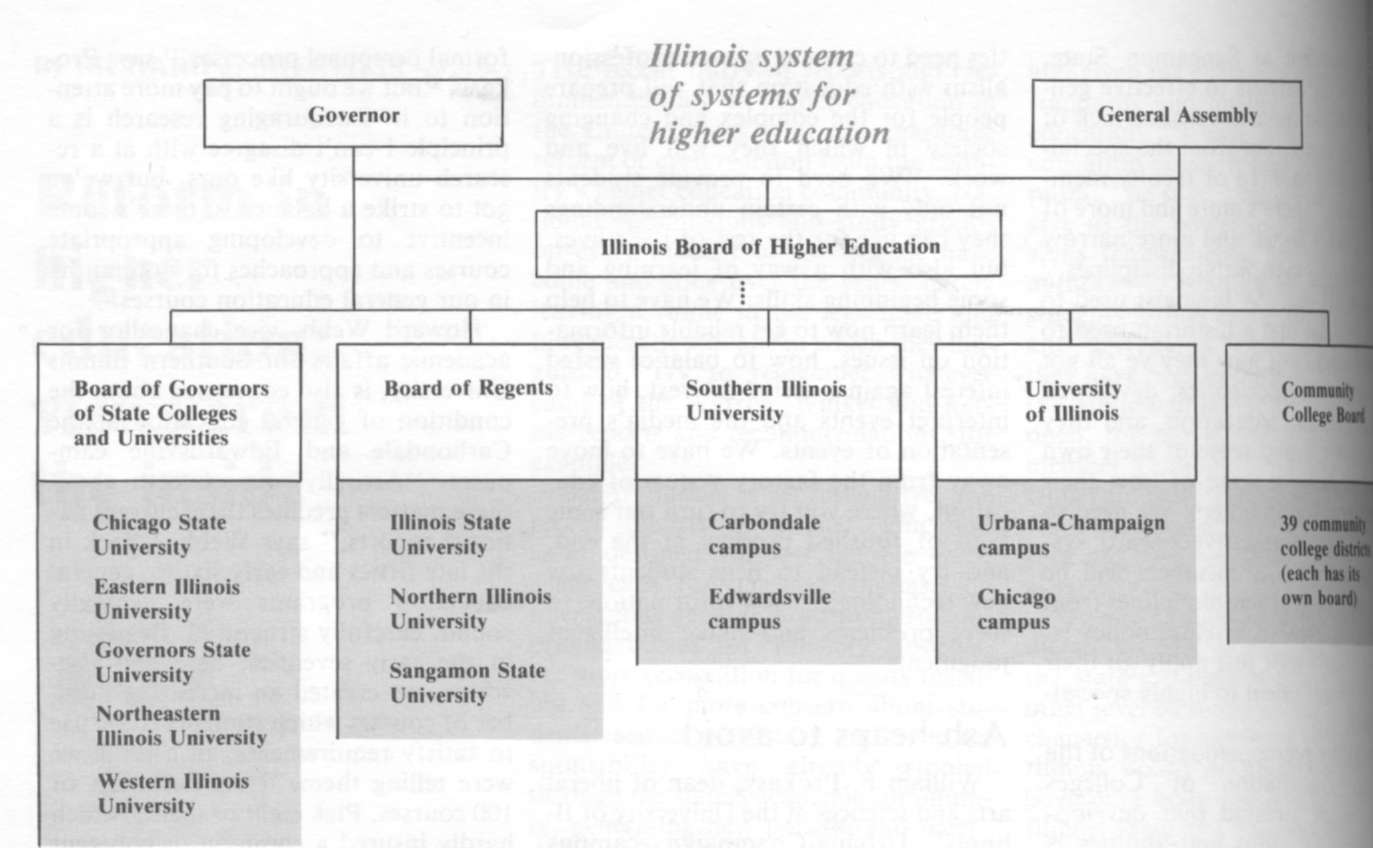

By RICHARD J. SHEREIKIS Reform in higher education: views from the inside  Higher education has awakened in Illinois. Education leaders from campuses and boards throughout the Illinois system of systems were interviewed by Richard J. Shereikis, who asked them how Illinois should respond to recent national studies criticizing the quality of higher education. (Last month, Shereikis presented the major conclusions of these studies in "The questions of quality and utility of higher education.") When discussing these national reports with Illinois' higher education leaders, he found that they had already assessed many of the problems in the state and that changes are already underway to balance super specialization with liberal arts education. One of the greatest challenges may be to balance the need for tougher admissions requirements with the dreams of those wanting a college degree but lacking the academic preparation required by the new standards. THE recent flurry of reports and recommendations on higher education in the United States does not guarantee reform or even reaction from the country's higher education community. National commissions and study groups on every manner of social issue have come and gone over the years, barely leaving a ripple in the legislative and bureaucratic sloughs in which they languished. Try to remember whatever came of the Warren, Walker and Kerner reports and recommendations, for example. But if Illinois is representative, the recent reports on higher education seem destined for less ignoble ends. Their calls for renewed emphasis on liberal and general education, for improved access for minority students, for more recognition for quality teaching and for more concern about students' senses of history and civic responsibility have already rippled through the state's academic community, generating new policies and incentives in colleges and universities. In Illinois the spirit of reform predated the national reports in some areas, but educational leaders found the new attention a valuable aid in their efforts to make post-secondary education challenging and responsive, both to students and the larger society. Window open to change "The public interest in education gave us a window of opportunity to deal with policy issues that related to public education," according to Richard D. Wagner, executive director of the Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE), which is the coordinating board for the state's complex "system of systems" in higher education (see chart). Given that window, the IBHE took action to tighten admissions standards for students entering Illinois' colleges and universities. In a controversial recommendation last fall, the IBHE called for new minimum requirements for entering freshmen, including four years of high school English; three years of social studies, mathematics and laboratory science; and two of foreign language, music or art. Wagner acknowledges that these are perhaps the most public and emphatic recommendations the IBHE has ever made, but he feels they were appropriate, given the climate of concern about standards and quality in U.S. higher education. "I have a deep belief that education policy is best made on campuses," he says, "but our statute does give us the power to establish admissions requirements, and we used the authority to establish mandates so that students would come to our colleges and universities better prepared than they have been in the past." And while the window of public interest remained open, the IBHE also appointed a 22-member Committee on the Study of Undergraduate Education to develop ways of responding to the specific issues and concerns raised by the national reports. Wagner's reluctance to have the IBHE dictate specific educational policy for the state's campuses is echoed at another level by Roderick T. Groves, vice chancellor for academic affairs for the Illinois Board of Regents (B0R), the governing body for Northern Illinois, Illinois State and Sangamon State universities. "In 1983 we issued a report from a program committee on undergraduate education in the regency system," Groves points out, "and the report anticipated nearly every issue and recommendation raised by the national studies." The report recommended a number of policies to prevent excessive specialization in students' undergraduate studies, for example. In general, it urged that at least one-third of a student's course work should be in general education, and it encouraged the development of "ways in which the Board of Regents . . . can give greater visibility and encouragement to strong student and faculty performance." But Groves and the BOR share Wagner's belief that specific educational requirements and initiatives be left to individual campuses, which should be responsive to their own students' needs and expectations. Boards should make broad policy suggestions, like the BOR's on general education, but, as Groves puts it, "If there's anything worse than an absence of a guiding logic, it's administrators who dictate what should be done." Boards must offer guidance and support, according to Groves, but individual campuses must decide on their own methods for insuring adequate breadth and depth in students' undergraduate experiences. 20/March 1986/Illinois Issues Like many educators, Durward Long, president at Sangamon State, feels that the barriers to effective general education come not from a lack of will or guidance, but from the specialized training required of faculty members today. "There's more and more of a disciplinary focus, and more narrow specializations even within disciplines," Long points out. "A biologist used to know biology, and a historian used to know history. But now they've all got very precise subspecialities, developed in their graduate education, and they don't have a broad sense of their own fields, let alone a sense of how their disciplines relate to others. We need to create a more responsive reward system, so that faculty members will be encouraged to see their disciplines from the point of view of broader policy issues, so they won't just apply all their knowledge and talent to highly specialized research."

Echoing the recommendations of the American Association of Colleges (AAC), which stressed that development of certain skills and abilities is more important than specific course requirements, Long argues that universities need to counter narrow professionalism with education that will prepare people for the complex and changing society in which they will live and work. "We need to provide students not only with certain understandings they can use for the rest of their lives, but also with a way of learning and some beginning skills. We have to help them learn how to get reliable information on issues, how to balance vested interest against vested interest, how to interpret events and the media's presentation of events. We have to move away from the factory system of education, where you try to turn out some kind of finished product at the end, and try instead to help students use new technologies, new information, to solve problems and make intelligent judgments." Ash heaps to avoid William F. Prokasy, dean of liberal arts and sciences at the University of Illinois' Urbana-Champaign campus and a member of the IBHE's committee on undergraduate education, shares Long's analysis of the causes of some of the problems in current undergraduate education. "What's happened since World War II," says Prokasy, "is that the sheer growth in higher education has resulted in a need to expand graduate programs, which meant more research and more specialization in graduate education. These [national] reports are reactions to this kind of emphasis, not because the emphasis is wrong, but because it had gone too far. We've tended to push the attitudes and values of the graduate schools down to the undergraduate level, so there's more emphasis on the major now than on the larger corporate responsibility of the faculty. Since departments are primary arbiters on personnel matters, faculty have to prove themselves within the discipline, through research, so there's been some abdication of responsibility for the part of a student's work that isn't in the major area." To correct these tendencies toward specialization at the undergraduate level, Prokasy's college has instituted a number of distribution requirements for students, and it is seeking ways to encourage more effective and appropriate teaching in general education courses. "We attend to teaching in our formal personnel processes," says Prokasy, "but we ought to pay more attention to it. Encouraging research is a principle I can't disagree with at a research university like ours, but we've got to strike a balance so there's some incentive to developing appropriate courses and approaches for nonmajors in our general education courses." Howard Webb, vice chancellor for academic affairs for Southern Illinois University, is also concerned about the condition of general education at the Carbondale and Edwardsville campuses. "Actually, our concern about these matters predates these current national reports," says Webb. "Back in the late fifties and early sixties, general education programs were generally sound, carefully structured. Beginning in the early seventies, here and elsewhere, we created an increasing number of courses which students could use to satisfy requirements. In a sense we were telling them, 'Here's this list of 100 courses. Pick eight of them,' which hardly insured a common or coherent experience. And not all the courses were that solid, either. Now we've significantly reduced the number of courses which students can use to satisfy requirements, to give the curriculum more integrity. Both campuses are concerned that general education not become an ash heap, where mostly young and inexperienced faculty and graduate students teach, and we have to find ways to reward good teaching more in our personnel system, without giving up our commitment to scholarship." To lead, not react On the matter of declining numbers of majors in the liberal arts disciplines, a problem noted in all the national reports, Webb has a practical explanation. "No one seemed to notice," he says, "that the decline in the numbers of those majors corresponds with the decline in the number of people going into teaching, because of the poor market in that area. Cut teacher education programs, and you're going to see a decline in liberal arts majors, automatically. But if teaching becomes a popular field again — as it looks like it will — I suspect we'll see more liberal arts majors." March 1986/Illinois Issues/21  Reading currents and trends like those which Webb points out is the most difficult part of his job, according to Thomas D. Layzell, chancellor of the Illinois Board of Governors (BOG), which includes Eastern Illinois, Western Illinois, Governors State, Chicago State and Northeastern Illinois universities. "You're pulled so many different ways, if you're not careful, you spend days responding to others' agendas," says Layzell. "Obviously, we need to reexamine the baccalaureate degree and what it means, and make sure it's of high quality. Businesses are beginning to believe in the importance of liberal arts skills, like thinking critically. The public is concerned about the teachers we're turning out for the public schools, and the BOG universities turn out more teachers as a system than any other in the state. And we have to be concerned about the demographics of higher education, too, making sure we're reaching all the students we can. There are all these issues, and we to try to get out in front on them, to provide leadership and opportunities. I've just convened a committee, composed of people from the board and from each campus, to look into all these matters and find out what's going on within the system which might be helpful on all the campuses."

William R. Monat, chancellor of the Board of Regents system, shares Layzell's belief that universities must look and plan ahead carefully and not just respond to markets, trends and educational fashions. "We have to lead, not just react," Monat says. "And we have to be able to articulate what we're about, crisply and clearly, to legislators and to the general public. We have to take a look at what we're doing now and what we must be doing five, 10, 15 years from now. Changing demographics is the greatest challenge facing us right now, with minority populations growing rapidly in the state. We have to start in the preschools, finding ways to attack the problems of illiteracy and dropouts. Right now, for example, one of two blacks who enter Chicago's public schools never graduate from high school, and we need to find ways to correct that, to retain those students and give them chances to get educated. The universities have a role in insuring quality in elementary and secondary schools, through our teacher education programs. So we need to be sure that our baccalaureate programs mean something — that graduates know how to write, to think critically, to have a sense of citizenship and some sense of an umbilical cord to the past. We gave the shop away in the sixties when we got away from structure and common experiences in the curriculum." 22/March 1986/IIlinois Issues The IBHE's Wagner agrees with Monat's concern about the need to increase the numbers of minority students in the state's colleges and universities. An IBHE report published last May revealed that minorities' involvement in higher education decreased alarmingly at successive levels of education. Twenty-one and one-half percent of the state's kindergarten through 12th grade enrollment was black in 1982-1983, for example, but only 13.6 percent of high school seniors, 6.9 percent of bachelor's degree recipients and 2.8 percent of those receiving doctorates were black. "Our most important challenge is to enlarge the pool of those who are academically prepared each year, "Wagner says. "You can't train physicians if they haven't had strong science courses, and they can't get those if there's no high school science program. We've got to curb the high dropout rates by providing better programs so more students can have a chance to come to college." The IBHE's new entrance requirements are an attempt to encourage every school district in the state to make its curriculum broad and deep enough to prepare students for the challenges of college work. The recommendations have been controversial, some districts arguing that they can't afford to staff and offer the courses the state will be requiring by 1990. But the IBHE is hoping that the new requirements will encourage both school districts and legislators to meet the demands by rearranging their priorities and finances. Challenges to transition However the schools respond, the new admissions requirements will put new pressures on the state's community colleges, which already enroll over half (361,187 of 714,888 in 1984) of all the students enrolled in Illinois' colleges and universities, both public and private. Roughly 40 to 50 percent of the community colleges' students are in transfer programs, intending to pursue bachelor's degrees after they complete their associate degrees, and by 1990 all of these students will either have to fulfill the IBHE's new requirements in high schools or through supplementary programs in the community colleges. "The implementation of the new admissions requirements will pose a major challenge for the community colleges," according to David R. Pierce, executive director of the Illinois Community College Board (ICCB), the coordinating board for the 52 campuses which make up the state's 39 community colleges. "It will be a challenge on two fronts: for those who didn't fulfill the requirements but later decide they want to further their educations; and for those adults who dropped out of school — the rate is about 25 percent statewide — and don't satisfy those admissions requirements but who want to cycle back in and make up those deficiencies. We're going to have to sharpen up in terms of assessment, remediation and developmental work. As we admit students, we'll have to be more precise about where they're admitted in the cycle, and we may have to develop competency tests or other assessment measures. All that, plus continuing to offer the general education we've traditionally provided for students." Pierce is most concerned that the new policies don't deny access to the students which the community colleges have traditionally served. "The thing I'm most concerned about is not shutting doors on people," he says. "The biggest impact of all this will occur down the road, with adult students who decide after a number of years that they want to try college. We have to be sure we can help them get to the levels where they can satisfy the new requirements and pursue degrees. But I'm not identifying that as a problem in a critical way. I'm saying this is a challenge, and special things will have to be done; special kinds of attention will have to be paid." In terms of special challenges at universities in the state, Chicago State University in the BOG system has already implemented some programs that might provide examples of the special kinds of attention that Pierce suggests will be needed for poorly prepared students. Located on Chicago's south side, the university enrolled 7,404 students in 1984, 87 percent of whom were black or Hispanic. Like many urban universities, Chicago State has a student body which is older (28.8 in 1984) than the average and more inclined to attend part time. "There have been studies like the recent national ones going back a number of years," says George E. Ayers, Chicago State's president. "We knew what the problems were, and we've paid attention to designing solutions. Many of the students who came here were not well-prepared. Chicago has a school system with 432,000 students, but it can't provide the kinds of things that college-bound students need. Hardly any of the city's schools can offer the art, music and foreign language required by the new IBHE mandates, for example, so we'll have to develop provisional bases for admissions for many students."

Chicago State and other universities will have until 1990 to develop admissions policies responsive to the IBHE's new course mandates. Meanwhile, the university has taken steps to help students make the transition from high school to college. "We're already doing things to help students succeed here," says Ayers. "We're offering counseling right from the start, about college life in general and what to expect. We've got programs to help them develop the discipline for good study habits. We've got a grant from the IBHE that helps us bring parents to the university, to let them learn about what a university does, what kinds of demands it makes. This year, we started a program where every freshman goes through a special orientation program to help identify needs and weaknesses. "On top of that, we've developed close ties with local high schools. We've 'adopted' eight of them specifically, so our faculty can go in there and help teachers with course materials. With help from Borg Warner and The Joyce Foundation, we've got programs in computer science, math and reading where 150 local high school students spend half their day at their schools and half the day here, and in the last two years, kids from that program have won state math competitions. We run orientation programs for local schools, too, where we'll invite the entire senior class in to spend a day learning what we can offer; and I try to have the principals of local high schools come in for breakfast once in a while, to make sure they know what we're doing and to ask them for advice. And it's crucial to know that we've worked hard to make sure that the arts and sciences disciplines are part of the core curriculum for all our graduates, and that our college of arts and sciences is the second largest on the campus, because we believe in the value of those disciplines." March 1986/Illinois Issues/27

It is also important to note the role which faculty played in helping to preserve those disciplines at Chicago State. The Board of Governors — the system in which Chicago State operates — is the only university system which engages in systemwide collective bargaining, and the University Professionals of Illinois (UPI) was instrumental in mustering support from the legislature when the history and sociology/ anthropology departments at Chicago State were threatened with termination by the IBHE in 1984. The UPI, the faculty bargaining unit, exerted pressure to prevent the terminations. "We argued that all college students had a basic right to study the traditional liberal arts, and we worked with Sen. [Richard H.] Newhouse [D-13, Chicago] to get a Senate resolution that said that," says Mitchell Vogel, former secretary-treasurer and now president of UPI. " The result was that those departments were preserved. We don't feel that the union should negotiate specific curricular matters, like course requirements and things like that; but we can negotiate matters that have to do with the tone and quality of a campus: opportunities for faculty research and development, incentives for better teaching and research, provisions for better working conditions that will improve the educational climate. We can and have already done these kinds of things through our contracts with the BOG." Margaret Schmid, who left the presidency of the UPI last December after more than 12 years in the office, echoes Vogel's views. "We have worked constructively with the Board of Governors staff and administrators. At our initiative, through the bargaining process, Tom Layzell has formed a committee which includes people from all the BOG campuses and the board, to talk about incentives that have worked on each campus, to share ideas and programs that might help all the campuses. Through our lobbying efforts, we can raise the consciousness of legislators about educational issues, and deal with the system staff, which is an important forum in which policy is shaped. Our efforts on behalf of the liberal arts at Chicago State are an example of how the union can use its influence to maintain educational integrity and opportunity in the state's schools." To educate broadly If the state's higher education community is to respond to the issues raised by the recent national reports, administrators and faculty will have to work cooperatively; but they'll also need the help and support of concerned citizens like Nina T. Shepherd, the president of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. "I'm particularly concerned that we educate our students to be effective citizens," says Shepherd, a U of I alumna who was educated as a social studies teacher and has served as a trustee for 11 years. (The U of I board is the only governing board whose members are elected; members of other education boards are appointed by the governor.) Shepherd says, "We need to make sure we've got a core curriculum that helps students think critically, to write effectively and to be knowledgable in the sciences. Because for a while now we haven't had a sense of a core of common knowledge or goals, we've had no roots, no context for our education, and if people aren't broadly educated, they're going to be outdated in a short time. We have to get away from just training for jobs and help people develop a sense of civic responsibility." Esprit d'education Any examination of the current state of education — at all levels, in Illinois and elsewhere — reminds us of the circularity and interconnectedness of the major issues. Colleges and universities can only do a good job if the students who come to them are well-prepared in basic skills and understandings. The state's school children can only gain that preparation if the colleges and universities turn out competent, stimulating teachers. Competent, stimulating people will come to teaching only if society offers them attractive salaries and working conditions. Working conditions and salaries will be improved only if our schools at all levels turn out enlightened, forward-looking citizens who have developed a sense of civic concern and regard for their communities. To foster that concern, we might look to the recent Newman Report prepared for the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching by the Education Commission of the States, headed by Frank Newman. The report argued eloquently about the need for civic education to help our citizens see beyond their immediate personal needs and to take a role in building a humane society. And we might take a cue from the spirit expressed by President Joseph McKeen of Maine's Bowdoin College in a speech he made on the value of a college education: "It ought to be always remembered, that [colleges] are founded and endowed for the common good, and not for the private advantage of those who resort to them for education. It is not that they may be able to pass through life in an easy or reputable manner, but that their mental powers may be cultivated and improved for the benefit of society. If it be true no man should live for himself alone, we may safely assert that every man who has been aided by a public institution to acquire an education and to qualify himself for usefulness, is under peculair obligation to exert his talent for the public good." The fact that President McKeen expressed those views in 1802 makes them no less telling, and no less true today. Finally, the greatest challenge for Illinois' educational leaders may lie in restoring some of that spirit to the state's educational enterprise. 28/March 1986/Illinois Issues |

|

|