|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

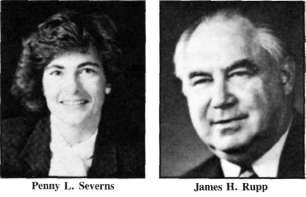

By ANTHONY MAN How did she beat the incumbent? Some of James H. Rupp's appearances in the 51st Legislative District's rural communities during the fall campaign may have hurt his reelection bid as much as they helped. Democrats fondly repeat a comment they heard after he stopped in Shelbyville, a city of 5,300 about 60 miles southeast of Springfield. The word on the street, according to one Democratic activist, was, "We haven't seen Rupp since the last election." Rupp's own Republicans, who pinned their hopes of retaining that seat for the GOP on the 10-year Senate veteran, admit that they heard the same refrain all too often. Two years earlier the political reporter at the dominant newspaper in the district, the Decatur-based Herald & Review, had complained to Macon County GOP Chairman H.G. "Skinny" Taylor that the senator was hard to find. That wasn't news to Taylor, who informed the reporter that Rupp never returned the chairman's phone calls either. "You heard it everyplace," Taylor now says. "People couldn't find him." Such situations may reveal the central factor in Penny L. Severns' capture of the central Illinois seat: Rupp himself. Insiders in both parties give due credit to Severns and her formidable campaign, but many also agree with William "Skip" Dempsey, chairman of the AFL-CIO Committee on Political Education for the 20th Congressional District. "He lost it," Dempsey says. Indeed, Rupp's support plummeted between 1982 when he got 37,200 votes and 1986 when he got just 27,600. At least the perception of Rupp wounded his effort. He was seen as out of touch with the district — an impression confirmed for many by inaccessibility — while Severns was seen as energetic and enthusiastic. Severns' campaign was, moreover, well-coordinated and aggressive and made the best use of a good candidate. Her manager, Linda Hawker, says, "He didn't have fire in his belly as she did." Severns herself attributes that to her devastating loss in 1980 to U.S. Rep. Ed Madigan (R-15, Lincoln). She had no intention of losing again. Severns perceives another important factor. "I represented not only a contrast in substance and direction . . . but a contrast in style and approach," she says. "While I would like to think [the victory] was the former rather than the latter, I have to admit it was the style and approach." Senate GOP staffer Mark Gordon, who was sent in during the last week of the campaign in an effort to revive the floundering Rupp effort, says it's impossible to pinpoint exactly what caused the defeat. In many ways, he says, a campaign is like throwing darts at balloons in the dark: You turn on the lights at the end to see who won, but you never know which darts hit which balloons. For the most part, Democratic partisans think it was their extraordinarily good candidate and coordinated campaign that scored with the voters. Others, including some Republicans, tend to believe that the Rupp effort failed to make any hits. "Theoretically, there's no way she should have won," observes Dempsey of the AFL-CIO, which endorsed Rupp on the strength of his voting record. "What it boiled down to . . . was a race for Rupp to win or lose and he made some bad choices." Those bad choices date back to his last victory, when he beat challenger J.E. Lee Miller in 1982, capturing 56 percent of the vote. After that, they say, Rupp avoided many of the rural areas in the district, although he remained somewhat more visible in Decatur, where he lived.

"He kind of let that southern part of the district go," Dempsey says. "He neglected it for four years that he was in there, That was a major problem." That was also a major opportunity for a challenger to make inroads in the rural areas — something that was exploited by Severns, who already had strong recognition in Decatur as a city council member. That was masterful strategy in the view of Gary Anderson, the mayor of Decatur, who had been courted as a GOP candidate in the event Rupp decided not to run. He estimates that 60 to 80 percent of the city votes were decided long in advance, while only 10 or 20 percent of the votes elsewhere in the district were firm. 24/March 1987/Illinois Issues Successful exploitation of that Rupp weakness was bolstered by Democrats' possession of all the elements needed for an upset: a great candidate, a skilled campaign apparatus and sufficient money. Republican Gordon labels Severns "an ideal '80s media candidate." The candidates were as different as their campaigns. "It was a contrast when they were together — the overweight incumbent and the new, aggressive, hard-pushing candidate," Dempsey recalls. That was underlined for the public by the campaign's emphasis on two priorities. Severns ran a modern media campaign using both advertising and free exposure and a person-to-person effort with lots of voter contact. The Severns drive never lost sight of the objectives, says campaign manager Linda Hawker, who was then a top aide to Senate President Philip J. Rock (D-Oak Park) and is now secretary of the Senate. "What we did in our campaign was provide the political sophistication of the 80s — for example the advertisement — with the grass-roots political campaign," Severns says. "So often candidates go one direction or the other and they don't combine the two." To do that the Democrats drafted a campaign plan seven months before the election and used it as the Bible king the election season. The blueprint included profiles of the two candidates and an analysis of the district's demographics. It contained the broad themes of jobs and leadership and detailed the campaign's milestones, such as contacting groups of voters by direct mail and telephone bank. Planners tried to anticipate every contingency and answer every possible question. "The very worst thing that can happen is somebody says 'Why are you running?' and you just stand there.' " Hawker says. An early use of some national polling data aided formulation of the plan. Information about public concerns was projected against each candidate's strengths and weaknesses to formulate general theme. "Know what your issues are, answer the question, and lead it into the things that you want to talk about,'' Hawker advises. Define an agenda. No matter what is said, respond in a few words and go on." When Severns was asked about her membership in and support from the National Organization for Women (NOW), for example, she responded that she did indeed join, along with Betty Ford, Rosalynn Carter and Lady Bird Johnson. When confronted with NOW's support for equalizing salaries for male- and female-dominated jobs, Severns would acknowledge that NOW wants equal pay and then change focus tthe campaign's issue: not enough jobs. Severns says that too many campaigns forget such a fundamental tactic, and Hawker says it prevented the campaign from getting diverted by something unexpected. It often tempting to make substantial changes based on the Rupp effort, Hawker recalls, but she says the campaign resisted as much as possible. Even as Election Day approached, the Severns side felt it imperative to stick to its formula. That helped maintain the campaign's control of the agenda, Serverns says that was partly good strategy and partly good luck. In any case, controlling the agenda allowed the Severns campaign to focus on what it believed were its best issues — jobs, utility rates and leadership. The Severns side chose these key issues early because they make a difference to people. Jobs was the main one. Whatever the issue, the campaign tried to swing discussion back to one of its themes. For example, Hawker says Severns was concerned about the school aid formula and its impact on the district. Rather than discuss the formula, a subject almost guaranteed to turn off most voters, Severns would say she wanted more education dollars for the district and then relate education spending to the jobs theme. "People liked (Rupp) and thought he was a nice man but didn't feel he was doing much," Hawker says. The objective of the plan and the campaign was to link the community's problems — high unemployment, for example — and the incumbent senator. Gordon agrees that's what happened, though he sees it negatively. "She was very adept at not making her positions the issue. She was very adept at talking at broad generalities with no specifics and avoided any debate," he says. "She figured out that she could win by pinning the economic problems on Rupp and went for it.  "In effect, focus all the anger and frustration on this incumbent senator. I think it was tremendously unfair, but it worked. For over a year, she had been very effective at avoiding any concrete issues," Gordon says. "I could tell she liked farmers, she was against unemployment and she supported education. That's all you could find about her." The victorious manager insists Severns' campaign did not ignore issues and the candidate "did not want to be sold like soap." Instead it shaped the message. "Voters only have so much attention," says Hawker, who sometimes urged the candidate to "talk about the things they care about and deal with the others when you get elected." The school aid formula was a prime example. "She was dying to talk about the formula, but people don't care. For campaign purposes you just have to say, 'We want our fair share.'" Hawker says that sticking to the plan is vital, though Dempsey believes the victors may give too much credit to their blueprint. He says they generally did a good job of keeping to their agenda, but they handled contingencies well. He gives much of the credit for that, as does everyone it seems, to Hawker. March 1987/Illinois Issues/25

Both candidate and manager say each had a defined role and stuck to it. Hawker ran the technical end while the candidate spent precious time on the important task of meeting voters. The grass-roots campaign — personal contact with voters — was supplemented by media. The campaign had a blend of commercials that bolstered Severns and knocked Rupp, accusing him, for example, of failing to sponsor "a single bill, in 10 years, to attract or keep business here." The television spot was accompanied by an unflattering picture of Rupp that accentuated his double chin. They were also adept at generating news coverage. Her campaign began by staging a series of Sunday press conferences to get exposure on slow news days. One such conference on the economy was held outside a closed factory, perfect for television and newspaper photographers. "Manipulating is a strong word, but she was excellent at that from the time she declared for office. She did very well at that," Gordon says. "For public people that's part of the game, manipulating the media. And she was running against a candidate that was not a media candidate." Severns had enough money to run both aspects of the campaign and maintain a credible challenge. In its early stages, the campaign plan set three budgets, the lowest acceptable of which was about $75,000 and the highest at $125,000. She took in about $90,000, including more than $18,500 worth of in-kind contributions. Rupp's disclosure statements show he had about $138,000, including $42,000 of in-kind contributions fromthe Republican State Senate Campaign Committee. The combined effect was much like the one that installed U.S. Rep. Richard Durbin (D-20, Springfield) in Congress after he picked off incumbent Paul Findley in 1982. Campaigns often borrow the best ideas from other efforts, and Severns unabashedly says she has taken many cues from the congressman.

By contrast, Rupp had problems. When Gordon arrived during the last full week of the campaign, it was probably too late. He immediately started more aggressive courting of the news media in an attempt to regain some of the ground that had been ceded to Severns. But, says Dempsey, "I don't think Rupp worked very hard until he realized it was slipping away from him and then it was just too late." (Rupp was unavailable for a post-election interview; there was no answer when repeated telephone calls were made to his home number in Decatur.) The entire campaign seemed late to some. Severns has been plotting her effort for years, and the GOP incumbent waited a long time before deciding to run, forcing the party to spend time courting potential Republican candidates for the post. Rupp also did poorly in joint appearances. Those who saw them together say they were stunned at the senator's poor performance, particularly after 10 years of toughening in the General Assembly and another 10 as mayor of Decatur. "Any time that they met in a joint meeting, she made him look pretty bad as far as losing his temper and saying things he shouldn't have said," says Dempsey. "It was obvious he was really irritated at some of the stuff she said and he let it bother him." When she discussed issues, he often went on the defensive, according to those who witnessed the appearances. By contrast, Severns was masterful at dealing with different audiences and got high marks for one-on-one contact. "He was responding to us, rather than us responding to him. That was his failure and our success," the winner says. Dempsey says the incumbent was given some bad advice and had a poorly run campaign. "It would probably have to march along side Adlai Stevenson's campaign," he says. "It just boiled down to, I think, Rupp did a lot of things very wrong." Joe McGlaughlin, the Macon County Democratic chairman, adds, "She's a tremendous candidate. I couldn't keep up with her. I'm a traveling salesman, but she put in some days." Anthony Mann is Statehouse bureau chief for Lee Enterprises. Before joining the bureau, he spent two and a half years as the political reporter for the Decatur Herald & Review. 26/March 1987/11 Jinois Issues

|