|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

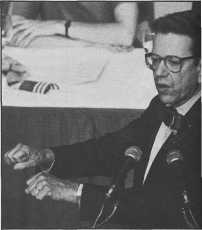

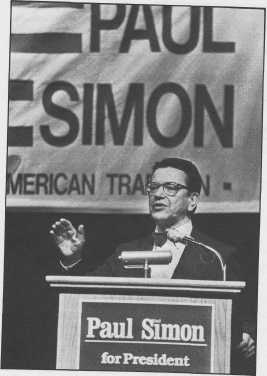

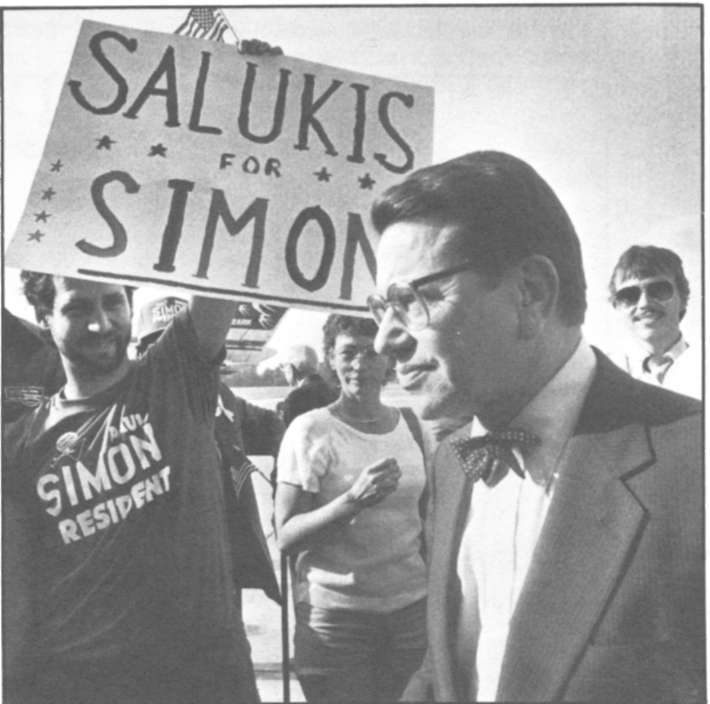

By PETER ELLERTSEN Paul Simon: First stop Iowa On the front porch of a renovated white frame house in a brick-street residential neighborhood of Daven port, Iowa, a hundred or so Democrats from eastern Iowa and the Quad-Cities gathered on a sunny Friday after noon just before Easter at the home of Davenport Mayor Tom Hart. They were there for a coffee-and-cupcake reception in honor of U.S. Sen. Paul Simon and his wife Jeanne on their first presidential campaign swing through Iowa. During most of a late-afternoon coffee hosted by Hart, first term mayor of this Mississippi River city of 103,264, Simon positioned himself by the porch steps shaking hands. He smiled at times and listened intently at others, speaking with most people a minute or two, jotting notes occasionally on the back of an envelope. "Iowa and Illinois are so much alike," Simon told a reporter who had come up from Springfield. "When I'm here, it could just as well be Springfield; and when I'm in rural Iowa, it could just as well be Route 1, Makanda, Illinois, where I live." From the beginning, Simon's presidential bid was universally conceded by even his friends in Illinois politics to be at best a long shot. ("I love Paul, but I wish he wouldn't do this," said one downstate political operative, who asked not to be iden tified in print.) Yet on the campaign trail in Iowa, Simon was in his element. In April and May an emerging consensus at the Statehouse in Springfield was that with a wide-open field for the Democratic nomination, Simon would have as much chance of winning as anyone. Simon's campaign strategy is an Iowa strategy, plain and simple. The scenario calls for him to do well in the Iowa precinct caucuses on February 15, 1988, then hold his own in the New Hampshire primary later in February and the "Super Tuesday" primaries in the South early in March. Then, the scenario goes, Simon could break away from the rest of the pack in the Midwest, starting with the Illinois primary on March 15. While it looks risky — and long-shot presidential scenarios look that way for good reason — it is a strategy clearly designed to capitalize on Simon's considerable strengths and minimize his weaknesses.  Simon entered the presidential race on April 9 with heavy liabilities — a "liberal" voting record, an image thought to be ill-suited to national television, a less-than-united Democratic party at home in Illinois. In the long run, he must overcome them to be considered a potential winner of the Democratic nomination and ultimately the November 1988 general election. Even in Iowa, in the very short term, he has problems. Just before the former front-runner, Gary Hart, pulled out, he led strongly in the influential Iowa Poll conducted by the Des Moines Register. Before Simon declared his candidacy, six other candidates were already in the race or about to declare. Among them former Arizona Gov. Bruce Babbitt, U.S. Sen. Joseph Biden (D-Del.) and U.S. Rep. Richard Gephardt (D-Mo.) already were building strong organizations in the state. Simon's chief tactical advantage in Iowa, at the time his campaign began, appeared to be nothing more promising than a softness of support for the other candidates. "People here like to keep their powder dry," said Mayor Hart of Davenport, an early supporter who said he had followed Simon's Illinois career in the Quad-City news media and respected his integrity enough to commit early. Mayor Hart predicted that Iowa Democrats wouldn't start pledging to presidential candidates in earnest til a month or two before the caucuses. When they do, he was unwilling to bet, Simon would be well enough known to command the respect and support statewide that he has already in the Illinois and Iowa Quad-Cities. If Iowa looks like an Upper Mississippi riverboat gamble, New Hampshire and the South look more like playing with a stacked deck against house odds. Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, whose national and Iowa Poll approval rates were climbing as the early campaign season progressed, is considered to have a lock on the relatively few Democrats in his neighboring state of New Hamshire. 8/July 1987/Illinois Issues In the South, Simon's liberal or progressive image is considered to be the kiss of death — especially by northern pundits. The candidate from Little Egypt in southern Illinois has promised only to exceed expectations and keep his candidacy alive on Super Tuesday. As Simon's candidacy officially started, it looked as if his toughest real competition in the South would come from the Rev. Jesse Jackson and from U.S. Sen. Albert Gore Jr. (D-Tenn.), who announced about the same time as Simon and immediately tapped into significant sources of big money available to progressive southern politicians. About the only thing Simon has going for him down South in these early stages of his campaign, although it is not inconsiderable, is the support of U.S. Sen. Dale Bumpers (D-Ark.) The second phase of Simon's strategy, as his campaign people explained it, is not in the South but in the midwestern industrial states. "For a spokesperson for putting people back to work there's simply [no one] his equal," a senior national adviser said in May during a background briefing. "While that might not be a great big deal in a two-and-a-half-percent-unemployment state like New Hampshire, just start somewhere around Philadelphia and go across the heartland and you're talking about very great numbers when you tick off states like Ohio, Illinois or Michigan. That is an important element, and it becomes more important in the middle [of the primary season]." Simon's greatest strength will come, the adviser predicted, in the industrial heartland bounded by Pennsylvania on the east, the steel producing center of Birmingham, Ala., on the south and Omaha on the west. The key to the Midwest, of course, will be the Illinois primary on March 15, the earliest in a northern industrial state. Even in Illinois, at least so it appeared nine months before the primary, Simon by no means will be guaranteed a free ride. For one thing, Jackson, with his political roots in Chicago, will share a measure of whatever favorite-son status Simon might enjoy. While Jackson has never established particularly warm relations within the Illinois Democratic party, he has articulated the dreams of the black community for years and could draw considerable votes in such heavily black Democratic bastions as Chicago and East St. Louis. Illinois Comptroller Roland Burris, pledged to neutrality by virtue of his post as vice chair of the Democratic National Committee, said in mid-May that he expected a wide-open primary. "It's going to be very interesting in Illinois. Illinois is a microcosm of how the nation is," Burris said. "Gephardt has support in Illinois. Biden has strong support in Illinois. In addition to Simon, of course, Hart had support, too. I think Dukakis is certainly trying to make some contacts. Illinois is split; the election currently is wide open. In my assessment, there's no front-runner right now." Simon had powerful supporters in Illinois by the end of his first month on the presidential trail, according to published reports. Among them are Atty. Gen. Neil F. Hartigan, state party chairman and state Sen. Vince Demuzio (D-49, Carlinville), State Treasurer Jerry Cosentino and House Speaker Michael J. Madigan (D-30, Chicago). Chicago Mayor Harold Washington helped Simon put together an early fund-raising dinner, but he was expected to remain neutral. As in Iowa, a large number of Illinois Democrats were keeping their powder dry. Simon's chief strategic advantage, it appeared at the end of May, was that no one else in the race enjoyed an advantage either. "We've got a tremendous field of utility infielders running in both parties. There are no Hall of Famers out there," said U.S. Rep. Dick Durbin (D-20, Springfield), who had backed Gephardt until Simon entered the race. Durbin's remark was widely quoted in April; a month later, after Hart fouled out with the bases loaded, it sounded even more appropriate. July 1987/Illinois Issues/9

Simon's other advantage, arguably his most important, is simply that he has always been a tireless campaigner who likes to talk about the issues. In Iowa, he has the added advantage of knowing the state's economic problems and having a finger on its political pulse. John Fitzpatrick, political consultant and longtime former administrative assistant to U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), who signed on early with Simon's campaign, said he believed Simon will stress the right issues in that heavily issue-oriented state and pull off an upset. "The issues frankly are very similar in Illinois and Iowa — agriculture, the economy, decent jobs, arms control," Fitzpatrick said in April. He might have added long-term health care to the list. A national campaign adviser who was with Simon early in the spring when he met with some of Washington, D.C.'s "message guys" (issues consultants) said a month later that long-term care may turn out to be the most compelling issue of all Iowa. The state has an aging demographic profile. However potent the health care issue may turn out to be, Fitzpatrick said Simon's key advantage will be his approach to the issues. "Paul Simon is very similar to the type of officials who get elected in Iowa all the time," Fitzpatrick said. Iowa has a history of electing prairie populists who take stands on the issues similar to Simon's. Perhaps more importantly, it is the discussion of issues rather than show-biz politics that tends to weigh heavily at the neighborhood level in Iowa. The state is highly literate, and its citizens are well aware that its agricultural economy is heavily dependent on world commodity markets. Winning precinct caucus support is more a matter of lining up precinct committeemen and neighborhood volunteers than it is of projecting images in 30-second television spots. The world of Iowa presidential politics is a world of small town rubber-chicken dinners, speeches at liberal arts colleges and in church basements, discussions at coffees, teas and other grassroots events. It is the kind of political milieu in which Simon has always done well. "Don't underestimate Paul Simon," wrote political reporter Tim Landis of The Southern Illinoisan in Simon's adopted home town of Carbondale, after watching Simon work the Iowa trail back in May. "A vintage Simon family campaign is begining in Iowa. It's a spare campaign, to be sure. It lacks the glitzy doo-dads that go with big-time presidential campaigns. Simon already acknowledges that he will be outspent by most Democratic candidates. But he won't be out-hustled." Landis, who spent a couple of days with Simon in Iowa, summed up the hunch of more than a few who had watched the opening stages of his presidential campaign. Certainly in Davenport on April 17 Simon's campaign already was well-launched. His issues, too, are vintage Simon. His "stump speech" is not all that new. Countless Illinoisans have heard these favorate Simon stands. For example, in Davenport, he plugged his longtime goal of better foreign language education in the context of the U.S. imbalance of trade and the need for saving jobs: 10/July 1987/Illinois Issues "We are in a trade war, and we are losing the trade war. I want to declare war on the trade deficit. We simply cannot tolerate what is happening in this area. You have lost 19,000 industrial jobs [in the bi-state Quad-City metropolitan area] already. You're going to lose 2,400 more in the next year and a half. We're in a trade war and we're losing. "But that can turn around. I used to be in business. I have some feel for how you do things, and you don't solve problems by ducking them. You face them, and you move aggressively on them. With research, with moving on the budget deficit, with a whole host of things. With an educational system that encourages foreign languages so you can sell your products. Part of it is simply in getting tough with our friends." He had given basically the same speech to 75 constituents at a town meeting April 4 in Mount Pulaski. His audience was in the storefront Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 777 hall on the old courthouse square. He told them, as he would repeat in later speeches in different places: "When we announced recently we would not have a quota on Japanese cars, I called a friend over in the White House and asked, 'What did we get in exchange?' figuring we sold them beef or pork or computers or something. And my friend in the White House said, 'Good will.' Now I like good will, but my banker is very unimpressed by good will. If I say I want to deposit good will, he won't give me very much interest on it." He Hammered on foreign language training as a trade issue: "We're the only nation on the face of the earth where you can go through grade school, high school, college, get a Ph.D., and never have a year of foreign language. That has to change." He has pushed the same idea in his recent books, The Tongue-Tied American in 1980, and again in The Once and Future Democrats in 1982. In the latter, he wrote: "... You can't sell your products effectively if you can't speak the language of the customer. The day we could demand that our customers talk to us in English is past; but our school system has not recognized that reality." Simon won few commitments if any in April when he shook hands and gave his emerging stump speech on the mayor's front porch in Davenport, but there was optimism from his Illinois backers. Illinois' 17th District State Committeeman Stewart Winstein of Rock Island, one of several politicians from across the river who attended the coffee, believes Simon's chances are very good in Iowa: "He's from a state that borders Iowa. He represents [a state with] all the same problems that exist in Iowa.'' Winstein paused a moment, taking in the ebb and flow of people shaking hands with Simon, and added: "And he's such a charming guy. Simon's a tireless campaigner, and his wife is a tremendous asset in the campaigning. I don't think he's that much of a long shot, I really don't." Peter Ellertsen is political columnist for the State Journal-Register in Springfield. He covered the 1984 precinct causes in Davenport, Iowa. July 1987/Illinois Issues/11 |

|

|