|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

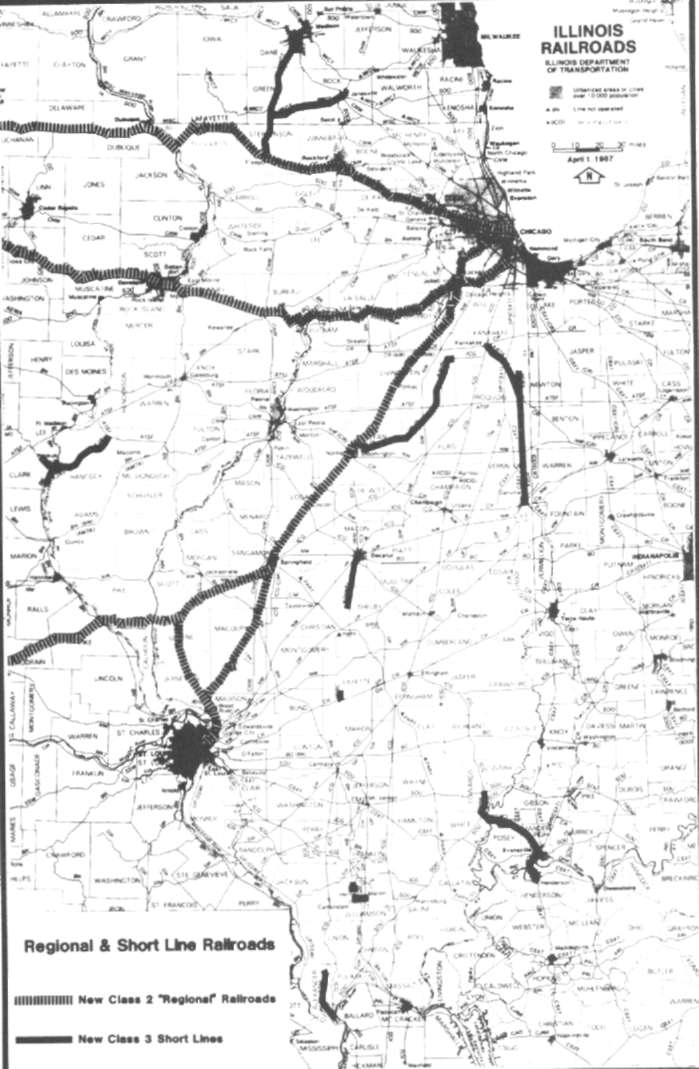

By NINA BURLEIGH Short lines over long haul In 1975, 48,000 Illinoisans were working on the railroads. Ten years later, their ranks had been nearly halved. During the same decade, the state lost 3,000 miles of track. The effect of this drastic structural change in a major industry on Illinois' unemployment figures or business climate has not been accurately defined. Merrill Travis, chief of the bureau of railroads at the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT), says that "it is very hard to tell" exactly how many jobs have been lost or how many shipping businesses have left the state because of the railroads' decline. On April 28, 1987, a new railroad, the Chicago, Missouri & Western (CM&W), was established in Illinois operating over tracks between Chicago and St. Louis and Springfield to Kansas City. The CM&W was created as a subsidiary of Venango River Corp., after a financing package was pulled together to purchase the track from the railroad giant, the Illinois Gulf Central. Truly an Illinois railroad, the CM&W with headquarters in Springfield has only 631 miles of track, but that track gives shippers access to five of the major railroad gateways: Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, Memphis and New Orleans. The CM&W exemplifies the new era of freight railroading: fewer behemoth-sized companies and more smaller, "regional" and "short line" operations hoping to provide better customer service and prices competitive with trucks. 'I don't think we'll see much Industry analysts say that Illinois, still the state with the highest number of rail employees and second in track mileage in the nation, has already felt the blow of the structural change that is sweeping the industry. "What's going to happen in the next 10 years all over the country with track abandonment has been happening here for the last 10 years," said Pat Simmons, legislative director for the United Transportation Union in Illinois. IDOT's Travis agrees: "I don't think we'll see much more track abandonment. ... We went through the pain first and now we're stabilizing. I hope in three or four years we have achieved a stable [track] base. The major wave of mergers is over, and the ICG [Illinois Central Gulf] raft of abandonments, which we are in the middle of now, will be over in two or three years." Recent history supports the notion that the worst has already happened. Two major Illinois railroads went bankrupt in the 1970s; between them, the Rock Island and the Milwaukee Road lines laid off more than 10,000 people. Illinois Central Gulf, one of the state's largest railroads, in the last three years alone shed 5,200 Illinois employees and hundreds of track miles in the process known in industry jargon as "downsizing" — streamlining a transcontinental giant into a core railroad. According to ICG president Harry Bruce, downsizing is almost over in Illinois. The streamlining involves another trend that is reshaping and, observers hope, breathing some new life into an old industry. In the process of getting rid of miles of track, not all the rails and ties are being torn up, and not all the track land is being sold for other uses, as was predicted not more than five years ago. Instead, new, smaller, regional and short-line companies are being formed, picking up track miles and business where the large companies pull out. Industry analysts view the advent of the regional railroads in particular as marking the end of the era of oversized, overregulated railroads. The beginning of the end was marked by the passage of the railroad deregulation act of 1980, known as the Staggers Act. It vastly simplified the process of doing business in the rail industry and of getting in and out of the business. It paved the way for the mergers of the giant companies, simplified tariff and rate setting by the Interstate Commerce Commission, and in what some view as a mixed blessing, allowed just about any one with enough money to come in and buy a railroad. Industry observers like Frank Haiti, rail freight program manager for IDOT, believe that deregulation has been the most important factor behind the change in the rail industry - more important than technological change and more important than changes in the trucking industry, which was deregulated in 1980 by the Motor Carrier Act but with less visible effects. Service and cost to consumers appear to be the keys for the railroads' resurgence. The Staggers Act allowed companies to set lower rates, but the key to making profits may be the willingness of railroad workers to shed their decades-old, rigid work rules and to tackle their jobs in the same entrepreneurial spirit as the new company owners. The new CM&W began operation with all its union contracts in place, company president John A. Darling said. It offered profit sharing in exchange for "more productive" work rules, such as two-man crews instead of the usual four- or five-man crews. 12/July 1987/Illinois Issues

The railroads' biggest competitors have been trucks, and railroads have generally lagged behind the trucking industry. According to John Gohmann, a Chicago-based rail management lawyer, trucks have long played a part in the downfall of the rail industry, and they have led the way in innovation. Says Gohmann, "Trucks have been bigger and better, and so are highways. The trucking industry is totally deregulated. More of them are non-union." Teamsters, says Gohmann, took pay cuts in 1986, while rail workers still settled only for pay increases. The railroad labor picture may change with the advent of the smaller, regional companies. The Interstate Commerce Commission last year identified 135 new post-1980 railroad companies nationwide. Most of them are short lines, and most either have no union representation or negotiated concessions with existing unions. Most of the new railroads can be classed as either regional or short-line companies. Because regional railroads are a relatively new phenomenon, however, they are not firmly defined. A good working definition for a regional railroad seems to be: smaller than a Class 1 railroad (companies with annual revenues of more than $86.5 million) but longer in track miles than typical shortlines (usually less than 100 miles). Regional railroads are created by bankruptcy, sale or merger of larger companies. An industry journal, Railway Age, identified 20 new or expanded railroad companies that fit this definition as of last year, and their numbers are growing. Three of the new companies are based in Illinois: the Chicago Missouri & Western (bought track from ICG), the Chicago Central & Pacific (also on track purchased from the ICG) and the Iowa Interstate Railroad (formerly Rock Island track). The first two are privately held by entrepreneurial corporations, while Iowa Interstate was created by an amalgam of shippers, governments and private interests. While the new CM&W found financial backing in the marketplace (Citicorp Industrial Credit, a part of City National Bank of New York), many of the new regionals have required federal, state or local aid. The bulk of federal aid comes in the form of Local Rail Service Assistance (LRSA) money and loan guarantees. According to Robert C. Hunter, director of the office of freight services at the Federal Railroad Administration, Congress has steadily rationed money to the LRSA and to railroad loan and loan guarantee programs, despite objections by the Reagan administration. The loan programs were begun in 1976 to address the major bankruptcies. Since then, in Illinois, the ICG and the Chicago & North Western companies have received low interest loans, as have emerging companies, such as Iowa Interstate, headquartered in Evanston. IDOT's Travis says that Illinois' share of LRSA funds has dropped from $5 million a year to $250,000 a year, which the state has tried to make up for in annual $3 million Build Illinois appropriations for the past two years. In fiscal year 1987, Travis said, the state has invested $16 million in railroad construction, but only one-third of that is actually state money; two-thirds is leveraging of private funds. Travis says IDOT has asked the legislature for $9 million this year. "In two years of reduced funding, we've been able to defer projects and leverage other people's money, but in fiscal year 1988, we expect a real crunch," Travis said. "I don't know if we'll get it. The needs aren't going away. The abandonments continue." Travis says Illinois' policy towards the rail abandonment by the larger companies is generally one of "intervention" only on behalf of "captive shippers" (companies that have no other way to ship products) and community economies. "Long before abandonment is mentioned publicly, we will have been put on notice," Travis said. "The ideal situation is if we see a line going down and can intervene early. There's a vicious cycle sometimes, because the railroads defer maintenance on lightly traveled track, and that makes the track less traveled and less profitable." The state only petitions the Interstate Commerce Commission against abandonments in a few cases, Travis said. But he said the Attorney General's Office has successfully fought all three cases it petitioned. Generally, Travis said, the Interstate Commerce Commission has been "rubber stamping" company abandonment requests: Out of 581 abandonment petitions in 1984, the commission denied three. As an example of successful state assistance, Travis points to the Crab Orchard & Egyptian railroad, headquartered in downstate Marion. In this case, a community economy was involved. All ICG track in downstate Herrin was up for abandonment, which would have resulted in more than 100 job losses directly, and the loss of shipping capacity for companies employing 7,000 in the area. The state contributed $775,000 (via the Department of Commerce and Community Affairs and IDOT) to help the tiny railroad company and the community buy the ICG track. The company started as a tourist attraction before the Staggers Act when the law did not allow a non-rail entity to become a railroad. Hugh Crane, president and founder of the Crab Orchard Line, said that deregulation drastically changed his company's opportunities. "There sure has been a change," he said. "When we started out [in 1972] we couldn't get the authority. The Interstate Commerce Commission was against short lines. But [for the Herrin deal] we got authority in a couple months' time." July 1987/Illinois Issues/13 A larger, shipper-oriented deal that succeeded with state assistance involved the Chrysler Corporation's Belvidere plant and Chicago & North Western (C&NW) railroad track. The state loaned C&NW $4.5 million using some LRSA money in order to refurbish 50 miles of track from West Chicago to Belvidere. The track refurbishment was part of a larger package deal offered by the state to induce Chrysler to stay in Illinois. Not all the state's ventures have ended as happily. One problem in the deregulation era is that more people are allowed to buy into the railroad business, and that, according to observers, has meant more "crackpots" in the buyers' pool. Said the ICG's Bruce, "Every rail buff, every guy who wants to be a railroad baron comes out." Bruce said the ICG has ''gotten very sophisticated about them in a very short time." Travis said, "We have had cases where people made offers and didn't seem to have the money. Usually, they don't buy in the end because they can't come up with the bucks. But it's a big deal in the community and in the press."

The state in the early 1980s subsidized track for Transaction Associates, a firm that went bankrupt because of management problems, according to Travis. That failure resulted in the total abandonment of almost 260 miles of track in two areas downstate. In another case, 120 miles of ICG track between Freeport and El Paso were up for sale but are now being converted to parkland and bicycle track because of delays caused by buyer problems. "A crackpot came in, made an offer to purchase, sent a check for tens of thousands to the ICG, and it bounced." Travis said. "Other legitimate buyers came in, but the first guy went to court. . . and meanwhile, the second set of buyers lost their funding. A lot of grain shippers, lumber yards and fertilizer dealers were affected. . . .It's unfortunate. . . . These deals are often very fragile, and if one party gets upset and goes to court, there's nothing you can do." The United Transportation Union (UTU), the largest rail operators' union, was part of the problem in a case near Decatur, according to Travis. UTU's Simmons admits that he regularly fights track abandonments. He said that the UTU often fights abandonments alone because shippers who would like to get involved can't afford the litigation. He added that the UTU has tacit shipper support in many cases. Deregulation has made the labor unions and shippers strange bedfellows in more ways than one. This year shippers, primarily utilities companies, are behind a move in Congress to repeal the Staggers Act. Calling themselves CURE (Consumers United for Rail Equity), the companies believe the Interstate Commerce Commission is no longer protecting the interests of shippers. Unions are threatening to back the repeal because one provision of the Staggers Act makes so-called nonrail entities that buy railroads exempt from the labor protection clause (seven years' pay and benefits to laid-off workers), which is applied to sales and mergers between larger companies. This key provision is hailed by management, and it promises to be an issue of contention as long as restructuring of the industry continues. Labor wants Congress to apply "labor protection" to the sales that are creating the new, smaller railroads. Both new Illinois regional companies, the Chicago Central & Pacific and the Chicago Missouri & Western, were "nonrail entities" under the law, despite previous interests in small railroads by both corporations. Says Simmons: "We should have never supported Staggers without that provision." Railroad management spokesmen have different regrets. They wish they had used the Staggers Act to "deconstruct" labor rules. Some labor rules date to the turn of the century, and industry observers often blame them for holding back technological changes that could make railroads more competitive with trucks. For example, one day's pay for on-train workers is still measured in 100-mile increments, in an age when trains may go several hundred miles a day. Other technological changes allegedly slowed by labor are the abandonment of cabooses and the advent of so-called roadrailers, truck-like vans with railroad wheels which eliminate the need for flat car carriers. 14/July 1987/Illinois Issues

Says the IDOT's Hartl: "Technological change ... is a slow process. . . Labor expenses need to be reduced in order for [railroads] to compete in productivity, so they are adopting technologies to reduce labor costs." Often, the burden of innovation has fallen to the new, deregulation-era regional and short lines, which have negotiated different types of contracts with unions. Dr. Paul Banner, chief executive officer of the Iowa Interstate, says that for his company, "Technology has been very important." Banner says the only way for railroad companies to survive today is by "departing . . . from their most labor-intensive areas and substituting labor for capital." Essentially, the move toward new technology has really meant smaller and more versatile working crews, rather than new, vastly different equipment. Unions have agreed to the new terms without much fuss. Often, the burden of Said Dan Collins, assistant secretary and treasurer of the national UTU: "Crew concept agreements can differ on shorter lines. If you get a brakeman who's qualified as an engineer, let him do it. That's the way we think we can enhance their job security. If you have 100 people on a railed, let them all do different things ... but companies should do the training." The prospect of a labor-shipper axis has incensed the ICG's Bruce. The ICG has been involved in the sale of $400 million worth of track to new or expanding companies: Eight regional railroads and nine short lines have been the result so far, according to Bruce. He says that they are all union shops, excluding "those that are so small they are mom-and-pop operations." His opinion of the shippers who make up CURE: "These are people with cures for which there are no diseases. I am very critical of the chief executive officers of these companies. They are the same guys who get up at executive dinners and talk about free enterprise and dare to put the word free in front of it." Although the three new Illinois regional railroads have unions, Simmons of the UTU is not satisfied. UTU's membership has been halved in Illinois in just six years. Simmons was particularly angered over the way the new companies help the large companies avoid the labor protection provision of the Staggers Act. In at least one Illinois case, a regional buyer put a previously owned rail company in a voting trust in order to qualify as a nonrail entity, Simmons said. He predicted: "The minute the little companies start to make money, the big companies will start to buy them up again." By all indications, Illinois' existing short lines and regional railroads are doing well. The newest one, the CM&W, will be investing $65 million over the next five years in rebuilding the railroad's infrastructure. The time is ripe for even more small railroads to emerge. The large railroads are eager to shed track. ICG president Bruce is an outspoken advocate of streamlining his own industry: "Some businesses really should go out of business. We hold onto rail lines like grim death, like Moses came down and said there should be a railroad here. But you've got to take into account . . . some railroads have been around since there were nothing else but goat carts. The whole corpus is going to die if you don't take off some of the appendages." The ICG, owned by IC Industries, could itself be sold someday. Divestiture of the railroad is one of the company's goals, according to a 1985 annual report. Tom Dorsey, vice president and general counsel of the American Short Line Association, a 73-year-old organization, believes that those "appendages" can thrive on their own. "These branch lines are very expensive for the Class 1's to operate," he said. He predicts that in several decades "instead of 350 short railroads, we'll have as high as maybe a thousand — whether you call them feeder, regional or short lines." The view he paints is strikingly similar to the national rail picture of the early part of the century, when the highest-ever number of short lines operated. Then, in the 1920s, the large companies began to merge and gobble up the smaller lines. While Dorsey's prediction falls on the extravagant side of the spectrum (some Wall Street observers believe the rail industry will be nationalized by the year 2000), it might not be that far off the mark. Certainly, "no one foresaw" what has occurred in the industry since the passage of the Staggers Act, says Bruce. In fact, when Bruce became president of ICG in 1983, it was expected that the company would be involved in a megamerger. Instead, it has been sold, piece by piece, to smaller companies. Nina Burleigh is a Chicago free-lance writer who has covered state and local issues in Chicago and Springfield for the wire services, the Chicago Daily Law Bulletin and WMAQ-TV. July 1987/Illinois Issues/15 |

|

|