|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

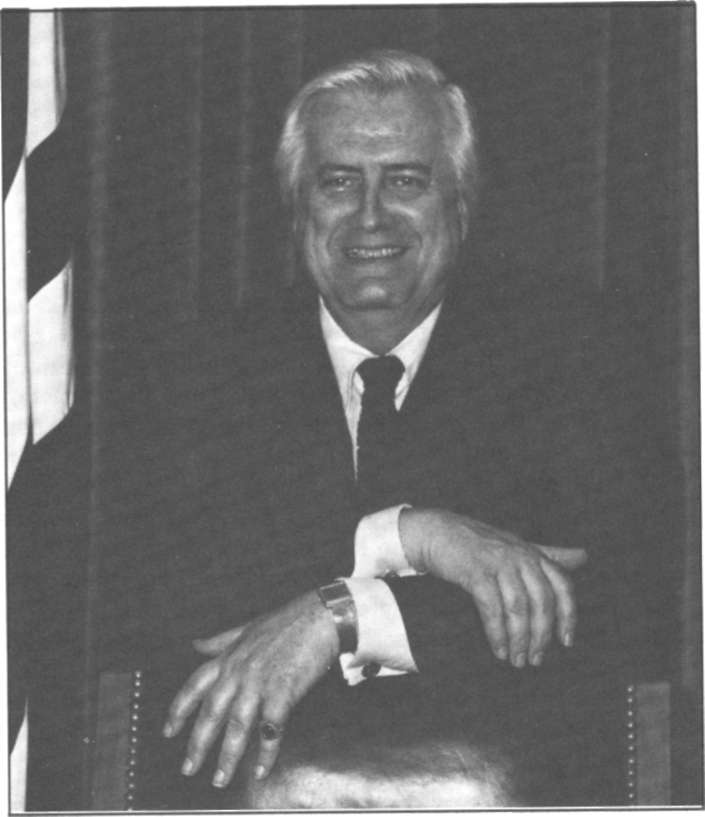

Henry Hyde: 'an effective, principled conservative'

Henry Hyde would hardly agree. As a congressional newcomer from the western Chicago suburbs, he won instant fame in 1976 with the Hyde amendment that greatly limits Medicaid funding for abortion. It stands as an example of the ability of a man with a belief to alter government policy. Arguably, Hyde, through the amendment, has had a greater impact on American life than all but a few congressmen. "In any event, I like to feel that that amendment helped some children get born that would have been exterminated; not terminated. Every pregnancy terminates. Exterminated is a more accurate word," says Hyde (R-6, Bensenville). "If you believe abortion is killing human life, an innocently inconvenient human life, then this legislation was in support of human dignity and human rights." To this day, Hyde's name is linked with the abortion fight, just as Rep. Kenneth Gray (D-23, West Frankfort) got the moniker "prince of pork" for his prowess in landing federal projects for southern Illinois or Rep. Edward Boland (D-Mass.) is known for the Boland amendment to shut off U.S. military aid to the Nicaraguan rebels. Hyde is proud of his anti-abortion role but rejects the one-dimensional label. "I would like to think my mark in Congress" is broader, Hyde says, pointing to his interest in U.S. military strength and conservative foreign policy. "I am somewhat disappointed when people speak of me, they think of that issue." The congressional investigation of the Iran arms-Contra aid dealings may change that. As a member of the House Foreign Affairs, Judiciary and Intelligence committees, Hyde was a natural choice for the special Iran committee. The assignment has meant innumerable opportunities for Hyde to argue the conservative cause and the need to help the Contras. "The real question is the future of the country in a dangerous world," Hyde said in an interview shortly after the beginning of the committee's televised hearings. "It's a pretty tough position to be in," he said of his job on the committee, which entails defending the idea behind policies that went wrong and trying to blunt cheap shots — all without whitewashing wrongdoers. "The Democrats piously say they don't want a wounded presidency, but it is like an undertaker at a $50,000 funeral trying to look sober . . . ." The arms deals, he quickly said, were "wrong, improvident, unwise. Thereal question is, were any laws broken?" Hyde is quick on his feet, a persuasive, passionate speaker who knows how to zing an opponent with a deft phrase. When New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, one of the most skillful orators among Democrats, in 1984 tried to define how Roman Catholics should balance their church's view on abortion with the duties of holding public office, Hyde made the answering speech at the University of Notre Dame. It called on Catholics to enforce the law but to also try to change it. He threw in a gibe: "At the extreme we have the sort of Catholic politician of whom it's been said that 'his religion is so private he won't even impose it on himself.' " Early this year, Congressional Quarterly described Hyde as "one of the premier orators of the House" and listed him among a handful of congressmen who wield influence without holding a leadership post. The Almanac of American Politics in its 1986 edition describes Hyde as "one of the Republicans' most competent legislators." August & September 1987/Illinois Issues/21  "The whole leadership thing is a vaporous thing," says chief deputy GOP whip Edward Madigan (R-15, Lincoln), because leaders are the people who take charge on an issue, not necessarily the representatives with the titles. "I regard Henry as being an extremely articulate and effective person." Madigan makes the flattering comparison of Hyde and Majority Leader Tom Foley (D-Wash.), also an Iran committee member. "They are both intelligent, both quick-witted and have an unusual capacity to express themselves." As well as oratorical skill, Hyde also can point to legislative victories. He took a leading role in defeating the nuclear freeze resolution in 1982 — "government by bumper sticker" — and weakening it in 1983. He was a crucial backer in 1982 of extending the Voting Rights Act. On many issues, Hyde is the most masterful debater for conservative House Republicans. Hyde could be a modern version of the happy political warrior. He seems perpetually upbeat and genuinely liked by his colleagues, although some on Capitol Hill find his wit a bit too sarcastic. "One of the most decent and delightful people to work with I've ever known," said Sen. Alan Dixon (D-Belleville), who disagrees with Hyde philosophically. "As an exponent of his views, you couldn't find a better person." Born April 18, 1924, in Chicago, Hyde, a Roman Catholic, grew up in a Democratic neighborhood. His first vote for president went to Democrat Harry Truman. "Thomas Dewey [the 1948 Republican nominee] did not resonate with me," Hyde says. In 1952, however, Hyde campaigned for Republican Dwight Eisenhower. Hyde said he moved to the GOP partly because he identifies with the underdog — a fitting description of Republicans in Chicago — and due to uneasiness with the direction of the Democratic party. "I always say Eleanor Roosevelt made me a Republican," Hyde says, citing the W.C. Fields saw, "'Twas a woman who drove me to drink . . . and I never had the decency to write and thank her." While going to law school at Loyola University, Hyde worked as proofreader at the Chicago Sun-Times and regularly had to read her column with an eagle eye. He received his law degree in 1949 and became a trial lawyer. 22/August & September 1987/Illinois Issues After an unsuccessful campaign for Congress against incumbent Democrat Roman Pucinski in 1962, Hyde was elected to the Illinois House in 1966 and became one of its sharpest debaters. He was elected majority leader in 1971 but failed two years later in a campaign for speaker. One still-relished story recounts how Hyde marched to the rear of the House chamber and claimed a seat among the "mushrooms," the legislators with desks beneath a balcony. Soon after, Rep. Harold Collier (R-6, Western Springs) decided to retire. Hyde dominated the 1974 GOP congressional primary and won the general election by 8,000 votes over former Cook County State's Atty. Edward Hanrahan — notorious for the police raid that killed Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark — despite the anti-Watergate tide that flooded Congress with Democrats. Hyde is now virtually invincible in the burgeoning 6th District; he won the last two elections with 75 percent of the vote. He represents white-collar territory in suburban Cook and DuPage counties, including O'Hare International Airport. (Hyde's office once arranged a White House meeting so local officials could complain about noise from the Chicago-run airport.) It is an area where people generally make enough money to worry about tax bills and can comfortably talk about getting rid of social programs. By Hyde's telling, "Almost by accident, I ignited a conflagration over abortion that still rages" — his well-known amendment that bars use of federal funds for abortion except in cases of rape or when the mother's life is in danger. Conservative Rep. Robert Bauman (R-Md.) suggested that Hyde should sponsor an amendment to delete $50 million for abortions from a 1976 appropriations bill — Hyde was an unknown freshman while Bauman would be a lightning rod for opposition. An irony in Hyde's victory was that anti-abortion legislators had been giving their attention to a constitutional amendment banning abortion. "The votes for an amendment were not there then and they still are not there today," Hyde says in For Every Idle Silence, a 1985 book containing Hyde speeches, essays and debates. On June 30, 1980, the Supreme Court ruled the Hyde amendment constitutional, and it is now routinely added to spending bills. The cause of the Iran arms-Contra aid scandal, in Hyde's view, was excessive zeal, not Watergate-style venality. Nonetheless, he worries over the damage to U.S. goals in Central America; "I think Congress has been wrong in its vacillating" over support for the Contras. At least one House member thinks the twists in Contra policy resulted from the hesitancy of either side to force a showdown for fear of defeat. During the early hearings, Hyde repeatedly pointed to Congress's shortcomings. "The nonfeasance of Congress may well turn out to be every bit as important as the misfeasance or malfeasance of certain individuals," he said one day. "I think he is causing Republicans to be more thoughtful and Democrats to be more judicious," Madigan said of Hyde's role. The scandal, Hyde says, "may set the conservative cause back several years. I think the conservative cause has been seriously damaged because the wisdom of its leaders has been brought into question.'' The scandal also encouraged splintering among conservatives. "On the other hand someone like [New York Rep.] Jack Kemp . . . may emerge as a rallying point," Hyde said, brightening with hope for his favorite for the Republican presidential nomination. One of Hyde's pet projects is elimination of the House and Senate intelligence committees in favor of a smaller, 18-member joint committee. That will mean tighter security and fewer leaks, he says, although opponents think it will weaken congressional oversight. The administration is far and away the leader in leaks, they say. Hyde was president of the 1974 GOP freshman class and lost by three votes in a 1979 bid for GOP conference chairman. He was mentioned as a possibility for GOP whip, the No. 2 spot, when Rep. Robert Michel (R-18, Peoria) moved up to GOP leader in 1980. Rather than chasing leadership posts, Hyde says he wants to concentrate on his interests, like foreign policy, foreign intelligence and writing. Hyde is a man who stirs strong words, and who uses them. To some people, he is a hinderance worthy of only short notice. It is presumption to impose his views on an intimate question, abortion, upon other people, they say, and contradictory for him to embrace clerical activism against abortion and then to lead two dozen congressmen in disagreeing with the Catholic bishops' pastoral letter against nuclear weapons. The congressman signed a letter that suggested the bishops misread the situation: "The crisis we face today does not involve two morally equal forces but the contention of human freedom against totalitarianism." The cause of the Iran arms-Contra aid For his part, Hyde repeatedly has defended the right of people to express political views based in religion, a liberty he traces to the founding of America. "I welcome religious values," he said in a 1986 interview while expressing discomfort "with more and more activity by churchmen as churchmen in politics." In the 1984 Notre Dame speech, Hyde said churches should not play a formal role in politics but church leaders have the right to speak on issues and the values that should guide decisionmaking. If that is not allowed, he said, "then an unconstitutional, illiberal act of bigotry has taken place." August & September 1987/Illinois Issues/23 In his book, Hyde expresses disgust that foes questioned the influence of religion on him as part of the court challenge against the Hyde amendment. "Some powerful members of the cultural elites in our country are so paralyzed by the fear that theistic notions might reassert themselves in the official activities of government that they will go to Gestapo lengths to inhibit such expressions," he writes. 'I'd like to communicate that even Asked how he wants to be remembered, Hyde quickly answers: "An effective principled conservative, who didn't take himself and the world too seriously but seriously enough. I'd like to be an influence for good. I'd like to communicate that even being a perennial loser," as Republicans frequently are in the House, "has merit if through what you say and what you do, you can move people to a better direction." Just as Theodore Roosevelt declared the presidency to be a "bully pulpit," so is the House to Hyde. "You can spread your ideas all ways in all settings. You have the opportunity to be listened to if you have something to say." Hyde's office is strewn with momentos — photos of Hyde with presidents dating back to Eisenhower, with Pope John Paul II and with Mother Teresa. There is a bronzed reproduction of a newspaper front page with a photo of Hyde addressing a massive anti-abortion rally in Ohio. On his cluttered desk one morning were letters from President Reagan and Henry Kissinger. Dominating one wall is a mural depicting George Washington on horseback, plodding with a group of Revolutionary War soldiers into a snowstorm. It seems an illustration of Hyde, too, laboring with the hope of eventual victory. Charles J. Abbott is a reporter for The United Press International in Washington, D.C.. concentrating on Midwest issues. 24/August & September 1987/Illinois Issues |

|

|