|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

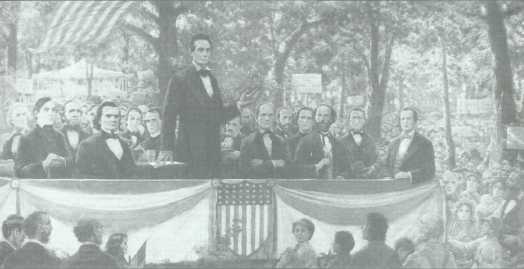

Illinois Issues Summer Book Section By CHARLES B. STROZIER Athens on the prairie: the Lincoln-Douglas debates  Photo courtesy of the Illinois State Historical Library Political debate is in a sorry state these days. Candidates and their staffs raise millions of dollars to produce canned ads for TV that never tackle an issue seriously, and the very notion of a thoughtful sound bite is an oxymoron. Negative campaigning, which has proven so effective, builds on a long tradition in American history, though it reached new depths, as well as gaining new legitimacy, with George Bush's 1988 campaign. A passive electorate that needs massive stirring even to vote expects little from its elected representatives, and gets less. Ironically, the only interesting political dialogue in the world right now is going on in eastern Europe. There are, however, some hopeful stirrings on the American landscape. A weary public may eventually rebel against mean-spirited TV ads. Serious campaign financing limits may eventually become a reality. And Illinois at least eagerly expects a lively series of debates this fall between U.S. Sen. Paul Simon and U.S. Rep. Lynn Martin modeled on the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. Martin, the feisty Republican challenger, has given the debates an appearance of reality they lack, for the two negotiating teams were only scheduled to begin discussion on format June 27. Simon, however, the secure incumbent and himself a noted Lincoln authority, will surely adopt a format that allows some comparison with the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas July 1990/Illinois Issues/27 Illinois Issues Summer Book Section campaign debates. There was then a vitality and integrity to political debate. Candidates talked about real issues at great length before audiences who they assumed knew something about political processes. They often pandered to prejudices but felt equally compelled to explain their positions on complex issues like centralized banking, the building of roads or canals at public expense, and most of all where they stood on slavery. The audience in turn listened to hours of speechifying and often complex argument about public concerns that overall made them a remarkably well-informed electorate. There was, of course, lots of nonsense and ballyhoo. It was common to roll out the whiskey barrel as the candidate arrived in town. A carnival atmosphere accompanied politics. At the edges of rallies, fights occurred, along with eye gouging and vicious biting, which were just some of the signs of 19th century maleness. There was plenty of voting fraud as well as fraudulent claims made by candidates. It was not always pretty, but it was fun and more or less focused on serious issues. Nowhere were these contradictions more apparent than in the extended dialogue between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas throughout 1858.

Douglas was the champion of what he called "popular sovereignty," or the right of local citizens in the territories to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery in their midst. Douglas had been trying for several years to apply the principle of popular sovereignty to the fierce debate over slavery in the territories as a way of calming tensions and opening up the West to railroad expansion; he also hoped to be president in 1860. Matters of principle and ambition had led to a major confrontation between Douglas and President James Buchanan. During the winter of 1858 eastern Republican leaders such as Horace Greeley felt Douglas's fight with the Democratic president could be turned to their advantage, and they quietly advised Lincoln not to run against him. Lincoln, however, felt such accommodation to Douglas's policies would be disastrous for the nation, for the fragile Republican party, and for his own ambitions to be a U.S. senator along the lines of his hero, Henry Clay. As winter waned Lincoln determined to oppose Douglas for the Senate race. He began quietly canvassing for support. He examined the 1856 election returns to establish areas of strength and weakness throughout the state and organize an effective campaign. He began noting ideas and speech phrases which he stored on bits of paper stuffed in his stove-pipe hat. Perhaps, he wondered, the recent struggles in Kansas were only part of a larger conspiracy actually to nationalize slavery. Perhaps even President Buchanan, Sen. Douglas, and the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Roger B. Taney, were secretly working together to make slavery legal everywhere, North as well as South, in the free as well as slave territories. By June he was ready. On the 16th, in the sultry heat of the legislative chamber in Springfield, Lincoln spoke to the assembled members of the state Republican convention. That afternoon the convention had nominated him as its candidate for the U.S. Senate. Lincoln spoke to accept the nomination and to outline his sense of the future. This extraordinary speech with its memorable "house divided" phrase and its outline of a dark conspiracy at the highest level to nationalize slavery immediately shifted the ground of the struggle between himself and Stephen Douglas. Historians have long doubted the existence of an actual plot to nationalize slavery, attributing such an idea largely to Lincoln's heated imagination. But there is no doubt the speech refocused the debate on slavery as the primary source of crisis in the nation. Over the course of the next month Lincoln and Douglas further elaborated their respective positions. On July 8, Douglas opened his own reelection campaign in Chicago before a large and boisterous crowd. He renewed his attack on the Buchanan administration and described himself as a lonely and heroic defender of self-government. He also launched into an extensive refutation of Lincoln's House Divided doctrine, which he described as a radical appeal for sectional war, an idea that Lincoln's Democratic opponents in Springfield had also voiced. The founders never intended the country to be all one thing or another, Douglas said, but rather a mixed system with slavery clearly protected constitutionally in the South. Furthermore, Douglas continued, Lincoln favored equality between the races, a view which failed to recognize that this government "was made by the white man, for the benefit of the white man to be administered by the white man." Lincoln, who had travelled to Chicago expressly to hear the speech, hastily arranged to deliver his own rejoinder the very next day. Lincoln dwelled at length on the meaning of equality in the Declaration of Independence and its simple and clear affirmation of "inalienable" human rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. He also addressed Douglas's race baiting by agreeing that the government was made for the white man, but he refused to accept that this meant African Americans had no rights at all. In what would become a familiar line, Lincoln noted: "I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife." He preferred to grant her more than she currently enjoyed — freedom — while carefully distancing himself from supporting racial equality. Not only had a debate begun but the key positions of each man were clearly staked out. As the underdog Lincoln's best hope was to relentlessly pursue Douglas and gain as much exposure as possible. Lincoln cleverly 28/July 1990/IIIinois Issues

challenged him to 50 joint debates. Douglas, always up to a good fight, accepted the challenge but pared down the number of debates to seven and fixed the format: On an alternating basis, each man spoke for an hour, the other replied for an hour-and-half, and the first then had a half-hour rejoinder. The debates began in Ottawa on August 21 and ended in Alton on October 15. They covered the geography of the state, from the free soil northern parts, to the pro-slavery areas of the south (called "Little Egypt"), to the deeply and evenly divided middle sections marked by a band of territory from Charleston to Springfield and extending west to the Mississippi River. These formal debates have justly entered American folklore as the greatest of their kind. Douglas, although short and fat, was one of the most vigorous stump speakers in the country. He played openly to the crowd and loved showy displays. He rode around the state in special trains draped in banners and arrived in town to the explosion of booming cannons. He sat back in his plush cars and sipped brandy and smoked fine cigars. During the debates themselves, Douglas, who owned slaves in Mississippi, wore what Republican commentators dubbed his "plantation outfit": a wide-brimmed felt hat, ruffled shirt and dark blue coat with shiny buttons, along with light trousers and shined shoes. One observer felt he had an overconfident expression, with his lower lip pulled over the upper, as if to say, "We will subdue you." Lincoln, for his part, was conspicuously modest and plain in his simple suits and top hats. He often came across as tall, awkward and ungainly, though his face always seemed marked by friendliness. His high-pitched twang had remarkable carrying power. Lincoln also had his own moments of drama: After the Ottawa debate, he was carried off the platform on the shoulders of his supporters; at one point he rode to a debate in a Conestoga wagon drawn by six white horses; he and Douglas were driven to the Galesburg debate on the campus of Knox College in two four-horse carriages driven abreast; and after the Quincy debate there was "a splendid torch-lit procession" in his honor, as reported in the paper. There is no doubt Lincoln was a better debater than Douglas. He had a much more subtle grasp of language and a deeper appreciation of rhetorical devices. From long experience he knew how to work a crowd and could pass easily from humor to eloquence. Douglas had a wooden ear to nuanced phrasing and evocative metaphors, and his comments during the debate were basically variations on the theme of his one set piece. But Douglas was a fierce competitor, alert to Lincoln's own contradictions and confusions, and himself passionately committed to his idea of popular sovereignty. Lincoln's most tenuous positions during the debates were those that dealt with racial equality. Modern readers might well wonder why, if slavery were so evil in Lincoln's mind, African Americans should be excluded from full social and political equality? Why was this just and humane man so stunningly explicit about not wanting, even in a theoretical sense, to make African Americans his equal? The answer in part lies in the politics of what was possible for Lincoln in 1858. America was a land with legalized slavery, one in which most southerners and northerners assumed white supremacy and detested people of color. One important source of free soil sentiment was thus a desire to keep slavery out of the territories so that they would not be overrun by African Americans. Lincoln, it seems, did not share such harsh views, and was himself without malice toward anyone. But as a politician in a land of racial hatred he necessarily moved toward the passions of the voters. It also seems fair to say that Lincoln harbored distinct ambivalence about full equality between the races. In 1858 Lincoln stated his beliefs repeatedly and with conviction; however regretfully, modern readers should grant that he was not a man to lie. But he never catered to race baiting, and in fact pushed his constituents toward much more humane positions. Slavery, he said, as an institution is morally wrong, a stance that severely challenged the pragmatic Douglas and appealed to the better human instincts of his listeners. Furthermore, in arguing that "Negroes" (his term) should be granted "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," as described in the Declaration, Lincoln was pushing for more than they currently enjoyed in American society, a politically perilous view that risked association with the abolitionists. When the final votes were cast, Lincoln lost the election. In the popular vote of some 250,000, he polled 4,000 more than Douglas. But in those days the state legislatures elected senators (this would change only in 1913 with the 17th Amendment). Some legislators had not come up for reelection in 1858, there was a suggestion of possible fraud in the popular vote, and a few districts were perhaps gerrymandered by the Democrats. The real reason for Lincoln's loss, however, seems to have been the difficulty of adequately assuring representation of the popular will through indirect electoral proceedings in such a close contest. So Lincoln, with 50 percent of the vote, received only 47 percent of what might be called the electoral vote. Stephen Douglas retained his position as senator from Illinois. It was a remarkable happening on the prairie. There has probably not been such public discourse since the high point of political dialogue in ancient Athens. It is not surprising the 1858 debates stand alone in the American experience. We can only hope they spark something equally intense and important in Illinois this fall. Charles B. Strozier, professor of history and co-director of the Center on Violence and Human Survival at John Jay College, The City University of New York, is the author of Lincoln's Quest for Union: Public and Private Meanings (New York: Basic Books, 1982). His recent work on Lincoln has appeared in Civil War History, the Quarterly Journal of Military History and other scholarly journals. July 1990/Illinois Issues/29 |

|

|