|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

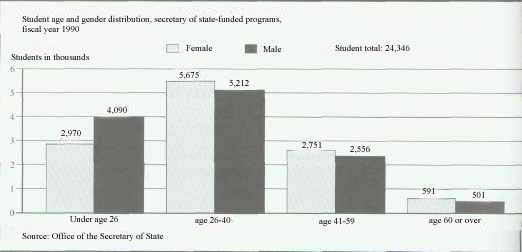

By GRANT PICK Adult illiteracy: a student-teacher case study  Photo by Kathy Richland Photography Doris Parker and Annie Sills This is the second in a series of three articles dealing with the problem of adult illiteracy in Illinois. The first article appeared in the October magazine and the last article will be in the December magazine. Annie Sills and Doris Parker meet together for one hour twice a week after work, on Monday and Thursday at the Blue Gargoyle, a social service agency on Chicago's south side. They both trudge up three flights of stairs to the top of the church where the Gargoyle is located. There Parker tutors Sills in reading, as one of 13,900 tutors helping nearly 25,000 students under grants awarded by the Illinois secretary of state. As is often the case in such relationships, Parker and Sills come from different worlds. Parker, a 58-year-old woman who barely breaks the five-foot mark, is executive director of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Educational Advancement Foundation, an offshoot of a black college sorority. Sills, 36, large and warm-faced, has spent her adult years working in a factory. She earns $16,000 a year. Sills and Parker are both committed to improving Sills' reading, and that has made them, although a little uneasily, chums. "Annie's a neat person to know," says Parker. "She tells me so many things about my mannerisms that we must be pretty good friends." Concurs Sills, "Doris and I have a good relationship. I know she's doing this because she wants to." Annie Sills grew up in Mississippi, where her parents were sharecroppers. "My mother was a so-so reader, and my father couldn't read at all," Sills remarks about the educational atmosphere in her home. "When I was coming up, sometimes I'd do my homework, but not like I should." At 16 Annie migrated north to Chicago with her brother. The following year she married. Three years later she went back to work in a factory. Today, as a single mother of a teenage daughter and guardian of a niece, she toils as a machine operator in a cup factory, but the passage of time has done nothing 18/November 1990/Illinois Issues

"When my daughter was in first and second grade, I could read along with her," relates Annie, "but as she climbed the grades I had trouble keeping up. She'd bring me her homework which was simple stuff and I'd say, 'They assigned you this.' I always signed the papers, but I didn't know what they said." Sills could read some parts of the newspaper "plain English," she says, "like Ann Landers" but she stumbled over the front-page news. She tripped over words in the simplest romance novels, which constituted about the only full-length literature she ever tried. Coming home from work she couldn't make out the names on the street signs. Eventually she had to make special modifications to get by; to facilitate her life on the assembly line, her daughter compiled a list of words she might need words like "electricity," "maintenance" and "over." Sills' husband Ralph, from whom she is now estranged, was graduated from high school, and he and Annie used to read together in bed. "But it ended up him always explainin' things to me," Sills recalls. "This has been very embarrassing," says Sills. "A little kid may ask me how to spell so-and-so, and I have to say, 'Go look it up.' That hurts. People look down on you." "At the church I go to, people have degrees from a lot of places, but if they find out that you don't know how to read, they look at you different and put you down. Or that's how I feel. One day a couple years back a deacon wanted me to read something from the Bible. I said I didn't want to. 'But, Annie,' he said, 'it's only a little short part.' I grabbed my daughter and ran to the bathroom, where we went over the passage. I try to keep out of those predicaments." Five years ago Sills enrolled in a literacy class at Chicago's Kennedy-King College. She found the class wanting, but it was only when she failed the GED (or high school-equivalency) exam that she "got disgusted and walked out." During the winter of 1989, while attending a boat show, she saw a notice for the program at the Blue Gargoyle and thought that having a tutor would be a better route toward her goal. Staff at the Gargoyle assessed Sills as a fourth-grade reader, and she was assigned a college student as a tutor. That initial pairing misfired. "She didn't have much patience with me," Sills says of her first tutor. "I think I must have been getting to her 'cause eventually she stopped coming.'' In May Sills was matched with Doris Parker. Parker grew up in Indianapolis. Her father was a laborer in an automobile factory. In Doris' most indelible memory of her mother, who died when Doris was eight, Mrs. Parker is reading bedtime fairy tales to her children. Whether due to that legacy or something else, as a girl Doris developed a passion for reading. "I think I read everything I could," she recalls. She was graduated from Indiana Central College (now the University of Indianapolis) and held jobs as a YWCA director and an administrator in a vocational college. She married, had two daughters and divorced. Reading remained a habit, with Parker's preferences running toward professional journals and nonfiction. She also learned the Laubach method of literacy instruction, a phonics technique pioneered in the 1930s by missionary Frank Laubach; yet her first experience at tutoring, which involved helping a white high school student, proved disheartening. "When her family discovered that I was black," Parker recounts, "the girl had no further need for a tutor." By 1987 Parker was a self-employed consultant when she moved to Chicago to take the sorority job. She has performed well, nearly tripling the endowment of the foundation she directs, which dispenses scholarships and grants. But early on she found it hard to meet people outside of work, partly because she boarded in a convent. Whatever the reason, says Parker, "getting used to Chicago this big, impersonal city was an adjustment. If I was going to stay, I needed to have something to do other than report to work every day. I had lived through the experience of being married to a job, and that isn't healthy." She decided to try literacy tutoring again. "If you know how to read, you have a responsibility to teach another person," Parker thinks. '"Each one, teach one,' the saying goes." The slogan was coined by Frank Laubach to convey his idea of volunteer tutors working to alleviate illiteracy. A sign posted in the Alpha Kappa Alpha lunchroom requesting tutors led Parker to the Blue Gargoyle and to Sills. "It made me feel funny to work with Doris at first," admits Sills. "Here she was with all her degrees working with me, a little ol' nobody." For her part, Parker found her student in dire need of assistance. She had Sills read from I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, an autobiography by Maya Angelou, and while Sills' comprehension was adequate she stumbled over word after word. As a consequence, Parker and Sills focused on vocabulary-building exercises. Sills also studied how various letters blend into sounds and how vowels and consonants mix with one another to make words. Yet particular bugaboos November 1990/Illinois Issues/19  plagued her; she tended to hear an "a" for an "e," she'd drop in an "r" where one didn't belong and her spelling stunk. "When it first appeared to me that things were coming together, it was December," Parker recollects. "Annie read me a story about Burt Reynolds. 'Okay, Annie,' I told her, 'write me something you found interesting about the story.' She wrote several sentences. Before, her sentences had been four or five words long, but now some sentences ran eight to 10 words. They were compound and complex, and they made sense. She was looking at my face for a reaction, and when she finished I was smiling. 'I must not have misspelled any words,' she said. 'We'll talk about misspellings later,' I told her, 'but I want to tell you, I am so proud of you. Look at how long your sentences are, and look at what sense they make.' " Still, Parker sometimes finds it exasperating to work with Sills. "Now with a child, you expect them not to know things," Parker explains, "and so your patience is greater. In a child's case, it's like you're taking an empty piece of paper and you are putting impressions on it. But with an adult, you expect certain impressions to already be there, even though consciously you know like with Annie that they aren't. It's hard sometimes not to be condescending. It's a delicate balance." Parker sometimes wonders to herself whether she is inadequate as a tutor. For her part, Sills admits, "I can tell when Doris is getting upset with me. When she's gone over something three or four times and I still don't get it, her forefinger will tap on the table. I can look at her and see that I'm getting the best of her." Once Parker was so frustrated that she fell on the steps when leaving a tutoring session; Sills, sensing the reason for the fall, called Parker later at home to make up. After Sills was in tutoring with Parker for a while, she enrolled in a GED class at the Gargoyle as well. Parker thought it premature for Sills to be going for high school equivalency, but after voicing her reservations she gave Sills a subscription to Essence magazine as an incentive. She also folded her literacy assignments in with those from Sills' GED classes; when Sills was reading science books, for example, her spelling words would concern science. Sills hired on at the Gargoyle several hours a day to encourage other literacy students. "I talk to other students, trying to get them to hang in there," says Sills. "A lot of them don't have confidence in themselves. Some I can convince, but others are determined to give up, the heck with it." In May Sills took the GED exam. Parker had opposed her taking it so soon, but Sills went ahead anyway, failing it by six points. She flunked it again in June, by four points. She came within three points in August. Yet her confidence is up appreciably. "I work on books from my GED class," says Sills. "I read Essence an article on Gladys Knight was very interesting. I'm writing longer and using bigger words." Spelling still vexes Sills; words like "calcium," "vertical" and "nuclear" leave her cold. Her ambition is to become a secretary, which will boost her salary, she figures. "If I could make more, I'd be all right," she says. In the interim, there is always Parker. "She gets tired of repeating herself with me, and she gets angry," says Sills, "but I wouldn't trade her for nothing." Says Parker, "I enjoy Annie. She makes me feel like I'm helping somebody do something for herself." The two occasionally socialize. They go out to dinner, and once they went to the theater, where they saw a musical reprising the life of the blues musician, Muddy Waters. When they stood side by side, the disparity in their height was noticeable. "I was way up high, and she was way down low," observed Sills, "but that didn't interfere with anything." Grant Pick is a free-lance writer living in Chicago. 20/November 1990/Illinois Issues |

|

|