|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

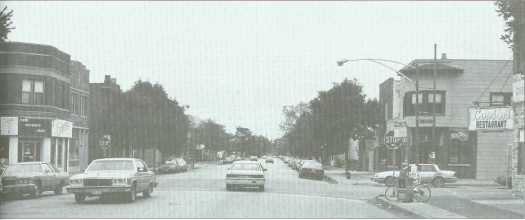

By DAVID FREMON Hegewisch: Chicago's most endangered neighborhood?  "Welcome to Hegewisch" reads the sign at 130th and Brainard, Hegewisch's northwest corner. From here, this looks like the entry to any of a hundred Illinois towns. Tom's Restaurant on the right has a large, unpaved parking lot ideal for the truckers who stop for lunch. On the left, The Corner Store advertises liquor and lottery tickets. Drive east, past modest brick houses with attractive flower beds and multilevel bird houses. On the right is a massive park with a football field, baseball diamond, tennis court and spacious field house. To the left, a new library is under construction. Turn right at Baltimore Avenue, the main street. The trappings of smalltown Illinois are in evidence a grocery store, flower shop, medical office and taverns, a hardware store, music store, savings and loan, pizza parlors. At the end of the street lies a train station, and not far away, a sawmill. A few blocks to the east, one can find a trailer park and a wildlife preserve by Wolf Lake. Even the ghosts of extinct businesses add to the small-town, homey feel. An "1888" marks the founding date of the one-time Hegewisch Opera House, located next to Cousins restaurant. The pillared former Hegewisch State Bank now hosts a tavern with a 40-inch television screen. The former Peoples Hall now has Mary Anns Shop ("the store for Miss & Mrs"). The Hegewisch, a former movie theater, now houses a Knights of Columbus chapter. The theater's spiritual descendent, a video rental store, is just up the street. A more thorough look jolts the visitor into realizing that this Norman Rockwell community is not part of Ford or Grundy county. Eastern European, not WASP, names predominate on local businesses. More important, there is no town hall; a 10th Ward office handles government affairs. The sign by the park reads "Chicago Park District Mann Park.'' A Chicago Transit Authority bus transports residents to South Chicago or the 69th Street el stop. Granted, Hegewisch seems more like a separate village than part of the nation's third largest metropolis. Hegewisch is about equidistant from downtown Chicago and Ogden Dunes in Portage, Ind., along the South Shore Line, the major transportation link with the Loop. Train schedules list Hegewisch as a separate Illinois entity, not another Chicago stop; and the sign in Hegewisch station calls the Randolph Street terminal "Chicago," as though it were a different city. The South Shore Inn, a bar near the station, has Indiana, not Chicago, posters: Indiana Dunes, Notre Dame, the 1987 Pan-American Games in Indianapolis. Las Vegas Night at an East Chicago Moose lodge. But the signs on the public schools, the post office, the library and the part-time police car (that Hegewisch shares with the neighboring community of East Side) don't lie. Yes, welcome to Hegewisch, Chicago's most southeastern, most isolated and as of February 14, 1990 most endangered community. December 1990/Illinois Issues/17 On that date, Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley announced his proposed site for a third major airport in Chicago, one that would displace part of the southeast side of the city including all of Hegewisch. "For two or three weeks early this year, residents called me about a survey that was being taken by the University of Chicago," says former Democratic state Rep. Sam Panayotovich, a Hegewisch native who followed Ed Vrdolyak into the Republican party. "They were asking questions like 'Would you move?' 'What's your home worth?' 'Do you like Hegewisch?' We had the feeling somebody was up to something, but we didn't know what.'' "It really came out like a thunderbolt," recalls Marlene Schichner of the Hegewisch Community Committee. "The day Mayor Daley made his announcement, the Sun-Times called here and asked what we thought about the airport. We asked, 'What airport?' " What airport, indeed. Daley proposed a 9,400-acre, $4.9 billion airport on the city's southeast side. The first three runways under the plan would be completed in 2010. Larger than O'Hare, the new airport is projected to create 200,000 jobs. Of course, this perceived boost to an economically stagnant area would have its downside. Some 47 major businesses employing 9,000 people would be uprooted. Parts of the Chicago community of South Deering and the suburb of Calumet City would be razed. So would all of the tiny suburb of Burnham. The present community of Hegewisch would be replaced by runway No. 2. Hegewisch residents could, if they desired, be relocated to a "New Hegewisch" proposed for an area south of 103rd Street and west of Torrence Avenue. Robert Repel, Daley's deputy in charge of the project, calls it a top priority of the administration. "There is nothing the mayor is more serious about than building an airport on the southeast side," he claims. But even with such unqualified backing from the city, its prospects remain anything but certain. A bistate panel has included it for consideration along with four other proposed sites: one in Kankakee County, one near Peotone, an Illinois-Indiana site covering part of Will County, and an expansion of the existing Gary, Ind., airport. The final decision should come sometime in 1991. Meanwhile, an uncertain Hegewisch sits and waits for the outcome. Uncertainty is nothing new for Hegewisch. It was founded near the marshlands of Lake Calumet and Wolf Lake in 1883 by railroad equipment manufacturer Adolph (some sources list his first name as Achilles) Hegewisch. He hoped for a self-sustaining, Pullman-type organized town for his United States Rolling Stock Co. Like many subsequent plans in Hegewisch, that one never quite worked out. Hegewisch, like Pullman, became part of Chicago when the city annexed the village of Hyde Park in 1889. Incorporation into Chicago prefaced other dreams of growth and industrialization which failed to materialize. A would-be canal linking Hegewisch and Wolf Lake with Lake Michigan never got beyond the planning stage. The Cal Sag Channel in 1911 brought some development but not as much as anticipated. Construction of a Ford assembly plant in the 1920s touched off speculation involving bog land in northern Hegewisch land which nonetheless remained undeveloped for another 35 years. But the area prospered, thanks to heavy industry from the Ford plant, the local Pressed Steel Car Co. (successor of United States Rolling Stock), the steel mills of South Chicago and the oil refineries in the nearby Indiana cities of Whiting and East Chicago. Irish, German and Swedish immigrants were the original settlers. A heavy influx of Poles after World War I made that group the dominant nationality. Despite improved transportation from automobiles and the Brandon Avenue street car, Hegewisch remained isolated by prairies and marshes from the rest of Chicago. In spirit if not in reality, Hegewisch stayed a village. Roads were unpaved. People kept goats and chickens in their backyards. During the Depression, fish from the nearby swamps served as breakfast, lunch and dinner for many Hegewisch residents. As in other isolated communities, the ma-and-pa businesses prospered. They continue to thrive. A Dairy Queen and a True Value hardware store are here, but otherwise national chains are conspicuously absent. "There's no McDonald's, no Burger King. People would rather go to Dorian's Pizza than Pizza Hut,'' notes Deborah Hanlon, editor of the Hegewisch Herald. "Most businessmen in Hegewisch are people who live here," adds Panayotovich. "People would just as soon go to the Hart's Foods store and pay a couple of extra pennies as go to Jewel or Dominick's." Hegewisch still possesses a small-town sense of security, and its crime rate is low. "People here know that if you leave town for a couple of days, neighbors will watch over your place, pick up your mail, water your tomatoes for you," says Panayotovich. Hegewisch does not even rate a full-time Chicago police car, but it hardly needs extra coppers. Ever since Mayor Richard J. Daley insisted that city employees live within city limits, an impressive number of policemen and firemen have decided to reside in the tranquil neighborhood. The economic problems that beset Rust-Belt America ravaged Hegewisch. The 1980 closing of the nearby Wisconsin Steel plant and the severe cutbacks of the U.S. Steel (now USX) South Works plant forced layoffs, early pensions or terminations to hundreds of residents. Industry, both nearby and from elsewhere, left another unhappy legacy. Because of the open space and distance from the rest of the city, hazardous waste sites were placed in this region. "Atty. Gen. Neil Hartigan has said the area contains 41 toxic waste sites and has asked the federal government that all be considered as a single site to facilitate receiving Superfund cleanup monies," according to Marian Byrnes, aide to state Rep. Clem Balanoff (D-35, Chicago). Airport proponents say that a cleanup of the area is one of the major benefits of the plan. Repel claims "a net environmental benefit." He says, "We will develop a mitigation effort to make the area much better." Robert Price, a city worker from Hegewisch who backs the airport, agrees. "I think the airport is the only thing we have [that is able] to clean up an area of contamination where the mills have been dumping for 50 to 75 years," he says. "I see no other way to clean up the southeast side." "Robert Repel said at a meeting here that the city will not 18/December 1990/Illinois Issues clean up the toxics from the area unless as part of airport construction," complains Balanoff, one of the airport's most outspoken foes. "But conditions already exist for a cleanup. People are dying here." Byrnes elaborates, "An Illinois Department of Public Health report showed a higher than normal incidence of some kinds of cancer in Hegewisch, such as prostate cancer in men and bladder cancer in women. A 1989 study from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency showed the southeast side to have a significantly higher cancer rate than the nation as a whole." The southeast side pollution, strangely enough, may be the factor that saves Hegewisch from the wrecker's ball, since a proper cleanup may prove expensive enough to outweigh the financial benefits of an airport. Comments Balanoff, "The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency [IEPA] did some digging in the Paxson Lagoons [a nearby waste site] and found things they didn't even know existed. Cost estimates for removal of the waste ranged from $ 100,000 to $200,000 per acre and could run as high as $860,000 per acre. Richard [J.] Carlson [then-IEPA director] said in 1987 that there isn't enough money in the treasury to clean up southeast Chicago." According to Balanoff, "The city opposes a study of the local groundwater. If they found something from that study, that knocks out the airport. Economically, the money for environmental cleanup just isn't there." Says Betty Vee Johnson of the Hegewisch Chamber of Commerce, "If they start tearing up these [landfill] hills, it could wreck the drinking water for the entire city." Pro- and anti-airport advocates differ on how much economic benefit will flow to the present residents of Hegewisch, who would be displaced by the airport. Repel points out projections of a $14 billion annual windfall to the city's economy and 200,000 jobs created. But Dave Orchowski of the First Federal Savings and Loan of Hegewisch asks, "What assurance is there that Hegewisch people would get anything above entry level jobs?" The economy could be worse, Hegewisch leaders admit, even after the downturn of the steel industry. "Steel mills are down, but smaller shops are coming up. There's a lot more professional people," Hegewisch Herald editor Hanlon says. Orchowski claims that 30 to 35 percent of Hegewisch residents work for the city and that another 20 percent are senior citizens. Yet in many respects, the uncertainty of the near future has paralyzed Hegewisch. "What industries are going to locate here, given the uncertainty of the possible airport?" asks Schichner. She adds, "Most people are likely to keep up normal maintenance of their homes, but they aren't likely to put on a $30,000 addition." Ironically, two major public improvements are coming to the neighborhood. One is a new South Shore commuter train station, two blocks southeast of the present one. The new station offers increased parking for commuters who drive here from throughout the south side and even from Indiana. The other is a new December 1990/Illinois Issues/19 60,000-volume, 12,200-square-foot branch library, which will replace the present cubbyhole on Brandon next year. Ground was broken for the library a month or two before the airport announcement. More than one resident has joked that the dedication day may coincide with the demolition day. Paul Bollheimer, Hegewisch branch librarian who headed the drive for a new building, downplays talk that it may be wasted because of the possible airport. "A library building is just that bricks and mortar. But the library is really the books and materials, and we'll have those materials no matter what happens with the airport. Also, it's foolish not to complete a project you've been working on for eight years. We've worked hard for the government money for the library. If you don't use that money, you lose it and have to start over. It's stupid not to do something because you think it might be gone in 10 years." The proposed airport may have already claimed a victim. Tenth Ward Ald. Victor Vrdolyak (older brother and successor of former Ald. Ed Vrdolyak) at first stated that the airport plan "seems to have more positives than negatives." Hundreds of irate telephone calls prompted him to change his position. The negative reaction he received might have been a factor in his decision not to seek reelection in 1991. Other politicians have met the issue head-on. Former Mayor Jane M. Byrne addressed and supported an anti-airport rally. Democratic committeeman Balanoff and Republican Panayoto-vich both ran for office in November (the former won his bid for reelection as state representative; the latter lost his race for county clerk), but both are among the candidates rumored to be running for 10th Ward alderman in February. Both have come out strongly against the airport. The proposal also stirred up grass-roots opposition. Citizens Against Lake Calumet Airport (CALCA) emerged immediately after Mayor Daley's announcement. A CALCA-inspired rally drew more than 1,000 people. CALCA also was able to place a referendum question ("Should an airport be built in the 10th Ward of the city of Chicago?") on the November ballot. Before the election, CALCA secretary Janice Chabicki predicted overwhelming defeat for the referendum. One Hegewisch leader said, "Voting for this airport is like voting for atomic bomb testing if you're living at Ground Zero." City worker Price countered with the view that a "silent majority" would favor it. The city pulled no punches in this referendum. Shortly before the election, 10th Ward residents received the "Lake Calumet Airport Update," a lavish four-color, four-page brochure extolling the virtues of the proposed airport. Voters, however, refused to buy its message. Just under 60 percent of them rejected the airport, with opposition coming from all parts of the ward. That number might have been greater, Balanoff claims: "The referendum question was printed on a paper separate from the rest of the ballot. Several precincts did not receive that paper until later in the morning those precincts being the ones expected to vote heavily against the airport." Part of the local discontent comes from the compensation package offered by the administration. As of November 5, the Chicago City Council had taken no official action concerning the proposed airport. Repel insists that the city would give business owners fair market value plus moving expenses and up to $22,000 in 1989 dollars, adjusted for inflation. Mike Aniol, whose family has run the local hardware store for 75 years, charges the city is only offering the "bricks and blocks" building value of a business without taking into account the "sweat equity" that it takes to build up a customer base over a period of years. Others charge that housing offers made by the dry are unfair since housing is undervalued in Hegewisch: A house similar to a $50,000 house in the community would cost two or three times as much elsewhere. Repel also proposes a relocation of the whole community, to a site near 103rd and Torrence. So far, "New Hegewisch" is an idea whose time has not come. "The mayor just put that suggestion in to combat the argument that we can't be compensated for our loss of community. That'll never fly it's silly," comments the Rev. Bob Klonowski, pastor of Lebanon Lutheran Church. Hegewisch leaders privately admit that part of that opposition may be racially based since "New Hegewisch" would be located near a black neighborhood. Some Hispanics and Arabs have moved into Hegewisch in recent years (the latter worshipping at an Arabic Christian service at the local Methodist church), but the community's population was less than 0.5 percent black in 1980, with no perceptible change since then. But a greater source of resentment arises from the potential loss of a sense of community built up over generations at the same location. Houses here seldom reach the open market. If not passed from parents to children, they get sold by word-of-mouth recommendation. Diners looking for a restaurant serving anything more exotic than a pizza are pretty much out of luck. Do you want a bookstore? Do you want high school football games? Forget it. But Hegewisch offers Golden Ager clubs, "the best Little League field in Illinois," Softball games, the Hegewisch Bulldogs junior football program, Sunday night bingo at St. Florian's Church and an annual Hegewischfest. "It's an old community where people feel comfortable leaving their doors open at night," says Balanoff. "Your grandfather, your father, you and your children attended the same school and church. You walk down the street, and you know everybody on the block." Some of those fathers and grandfathers might have shown up at Mann Park on a December day in 1976 when Mayor Richard J. Daley, accompanied by then-Ald. Ed Vrdolyak and then-Park Supt. Ed Kelly dedicated the new fieldhouse. At a basketball hoop, Vrdolyak and Kelly missed free-throw attempts, while Daley swished his try. It was the mayor's last official act. Hours later, he died of a heart attack. Daley the father dedicated a fieldhouse in Hegewisch. Will Daley the son dedicate runway No. 2? David Fremon is a free-lance writer in Chicago and author of Chicago Politics Ward by Ward. 20/December 1990/Illinois Issues |

|

|