GROUNDWATER:

WHERE IT COMES FROM,

WHERE IT GOES

By SAMUEL V. PANNO, Illinois State Geological Survey

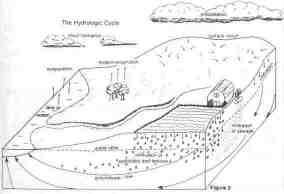

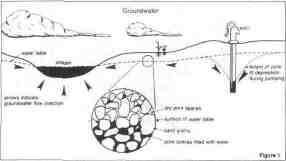

Have you ever wondered where the water in a well

comes from? Does yours draw from an underground

river or lake? Groundwater is water present in the tiny,

often microscopic, interconnected pore spaces between grains of sand and gravel and in open crevices in

rock (Figure 1). It is the source of drinking water for

half of the state's residents and almost all of its rural

residents. However, groundwater resources are not

uniformly distributed and can be contaminated and/or

depleted by careless, wasteful habits.

The water from rain and melting snow that infiltrates the soil and is not used by plants travels downward to the water table; below the water table soil or

rock is saturated with groundwater. Because ground-

water comes mostly from precipitation that falls locally, the water table may fluctuate several feet as a

result of seasonal changes, droughts, and periods of

heavy rain.

Under the force of gravity, groundwater generally

moves from higher to lower elevations, through the

connected pores and crevices of rocks and sediments,

until it discharges to a stream, spring, or pumping well.

Streams that flow even when no rain has fallen for

several weeks or months are being fed by groundwater.

Once discharged into a stream, the water begins its

journey at the surface. In Illinois, surface water and

groundwater flow to the Mississippi River and then to

the Gulf of Mexico. During its journey and after joining

the Gulf, water evaporates, eventually forming clouds

. . . and the cycle begins again. This cycle of water

movement is referred to as the hydrologic cycle (Figure

2).

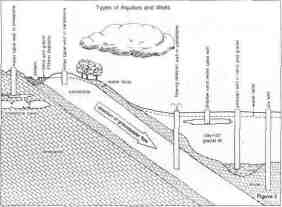

An aquifer is a body of rock or sediment that will

yield water of usable quantity to a well or spring. Clay-

rich glacial deposits and shale, which have low permeability and do not conduct water, act as confining

beds, restricting the movement of groundwater. Thus,

aquifers act as conduits bounded by less permeable

materials. Because groundwater moves through very

small spaces between the clay, sand and gravel, it

moves very slowly — at rates that range from feet per

day to only inches per hundreds of years. However, a

well in a good sand and gravel aquifer can pump millions of gallons of water per day. Sand and gravel

aquifers in Illinois produce 58 percent of the ground-water used; the remaining groundwater is produced

from bedrock aquifers.

Geology has a major influence on the availability of

groundwater. Glaciers that once covered most of Illinois deposited a blanket of materials covering the bedrock to depths of up to 600 feet. Clay-rich materials

comprise much of the glacial deposits. However,

June 1991 / Illinois Municipal Review / Page 27

streams flowing from the melting glaciers deposited

broad sheets and long, narrow bodies of sand and

gravel that now act as aquifers.

Bedrock aquifers were formed in a different

manner. These aquifers were deposited hundreds of

millions of years ago as layers of sand and fragments of

seashells in oceans that covered the land. These layers

hardened into sandstone and fractured limestone or

dolomite aquifers.

There are two main types of aquifers: the unconfined or water table aquifer and the confined aquifer

(Figure 3). Unconfined aquifers, recharged through

direct infiltration of rain water, are found in counties

with very sandy soils such as Mason, Kankakee and

Whiteside where aquifers lie only several feet below the

surface. Confined aquifers are covered by beds that

impede groundwater movement into and out of the

aquifer and cause the groundwater to be under pressure. The water level in a well in a confined aquifer is

above the top of the confined aquifer; this is referred to

as an artesian well. In flowing artesian wells, common

in southern Iroquois and northern Vermilion counties,

the water level is above both the aquifer and the ground

surface.

Tests to determine the specific capacity of a well

divide the pumping rate in gallons per minute by the

drawdown (vertical drop in water level in the well) in

feet. Pumping causes the development of a cone of

depression in the water table above the well (Figure 1).

To illustrate, imagine a snow cone with the crushed ice

as an aquifer and the syrup acting as groundwater. As

syrup is sucked out of the ice through a straw, the ice

fragments become whiter above the end of the straw as

the removal of the syrup creates a cone of depression.

Because aquifers are recharged at the ground surface, they are susceptible to contamination from anything (e.g., oil, pesticides, sewage) spilled on the

ground or buried. The substance can follow pathways

similar to those for groundwater. If the substance

reaches an aquifer, it may make the groundwater unfit

for use. It is very difficult to clean up an aquifer once it's

contaminated, and the process may be prohibitively

expensive.

Limited information exists on contamination of

aquifers by agricultural chemicals. Because some of

these chemicals are toxic at low concentrations, their

occurrence has raised concerns. Detection of

agriculture-related groundwater contamination in

neighboring states suggests that aquifers in Illinois may

be at risk. Research at the Illinois State Geological Survey, a division of the Department of Energy and Natural Resources, and other agencies is addressing this

issue.

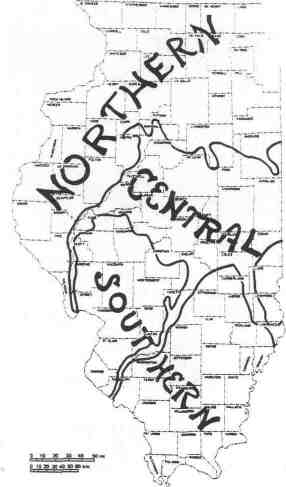

NORTHERN ILLINOIS

The availability of groundwater and the types of

aquifers vary across the state. The northern third of

Illinois relies on groundwater from three sources: (1)

glacial sand and gravel aquifers; (2) shallow dolomite

aquifers; and (3) deep sandstone aquifers. The dolomite is fractured and has solution features. Where there

are glacial deposits, groundwater that moves downward through them recharges the shallow dolomite

aquifers. In the western and northwestern parts of the

state where these rocks are exposed at the surface (e.g.,

Jo Daviess and Calhoun Counties) there is recharge

directly into the shallow dolomite aquifer. Relatively

large quantities of groundwater of predictable quality

are produced from the deep bedrock aquifers. The

earliest wells in the northeast in the deep sandstone

system had flowing artesian conditions. Heavy pumping from these aquifers near and in Chicago that began

after 1864 has formed deep cones of depression that

have dropped water levels in wells as much as 800 feet.

Small drops in water levels in these deep aquifers can

be detected more than 50 miles from Chicago.

CENTRAL ILLINOIS

The availability of groundwater and the types of

aquifers vary across the state. The dominant source of

groundwater in central Illinois is layers of sand and

gravel deposited by melt waters of the large continental

Page 28 / Illinois Municipal Review / June 1991

glaciers that once covered much of the state. The most

productive aquifers of this type are located adjacent to

the valleys of the Mississippi, Illinois, Ohio, Wabash,

Kaskaskia, and Embarras Rivers. Ancient river valleys

eroded into the bedrock also are buried beneath the

glacial materials. The Mahomet Valley Aquifer is an

example of a major bedrock valley located in east-

central Illinois. Its sand and gravel deposits are up to

200 feet thick, and it is buried under 100 to 200 feet of

glacial till. The aquifer underlies nine counties, ranges

from 8 to 18 miles in width, and provides a source of

water for irrigation, industrial, and municipal uses.

Groundwater withdrawal from the Mahomet Valley

aquifer is at least 42 million gallons per day. Thinner,

near-surface beds of sand and gravel, used by rural

citizens as sources of water, lie above the aquifer.

SOUTHERN ILLINOIS

The availability of groundwater and the types of

aquifers vary across the state. The topography of

southern Illinois was sculpted by running water from

melting glaciers, although some of the northern-most

part is overlain by relatively thin glacial deposits. Sand

and gravel, deposited by running water from melting

glaciers, is found along courses of present-day streams,

The most important aquifers in southern Illinois consist

of deposits of sand and gravel that lie above bedrock.

Sand and gravel deposits range from inches to up to 50

feet thick; layers several feet thick often are suitable

aquifers. Wells in these deposits provide water for municipal and farm supplies. Thinner, less permeable

deposits require large-diameter wells to produce water.

In upland and far southern areas where glacial till deposits are absent, bedrock deposits of sandstone and

fractured limestone will usually provide water for domestic and farm supplies. Limestone and dolomite that

make up the bedrock transmit water mostly through

fractures and solution features. Wells drilled into these

rocks yield water only if permeable features such as

fractures are intersected; the location of these features

is difficult to predict. The St. Louis and Burlington-

Keokuk limestones contain the most fractures and are

usually dependable sources of fresh water for farm and

domestic use. Mississippian sandstone, especially the

sandstone of the Aux Vases Formation, are most permeable and contain fresh water in the south-central

area. Unfortunately, the quality of groundwater decreases with depth because of the salinity of deeper

waters in the bedrock aquifers of southern Illinois.

Further information on groundwater protection,

conservation or location of these resources is available

from the Illinois State Geological Survey, 615 E. Pea-

body Dr., Champaign, IL 61820-6964. •

June 1991 / Illinois Municipal Review / Page 29