By JENNIFER HALPERIN

Illinois educators had high hopes for the 1980s when it came to minorities and higher education. The decade began with African-American, Hispanic and Asian students comprising a growing percentage of the enrollment at the state's public colleges and universities. Attention was focused on better preparing students of varied backgrounds for higher education, and a great deal of financial aid was being directed toward these so-called "underrepresented" students.

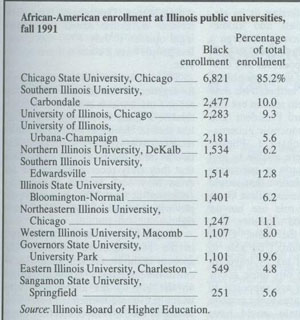

But as other minority groups' enrollment rates have continued to climb significantly into the 1990s, the rates for African-American students — males in particular — enrolled in in stitutions of higher learning have held steady or dropped since 1980. Anticipated gains failed to pan out, leaving educators and policy setters back at square one.

With the state's current tight budget in mind, Illinois lawmakers concerned with this issue appear to be taking a cautious approach to improving the situation. Rather than proposing to throw money into new efforts aimed at luring and retaining African-American college students, they're evaluating existing ones and watching the educational and economic climates to determine the best course of action.

"Let's face it — when money is good, minorities do well," said Chicago Democratic Rep. Art Turner, vice chairman of the House of Representatives' Higher Education committee since 1991 and chairman of its subcommittee on minorities in higher education. "When money is tight, only the strong survive. I would not say minority programs are a high priority now. If not for the subcommittee [on minorities in higher education], I don't think there'd be major discussion in that area."

"Higher education itself is just struggling to stay alive," said Turner. That being the case, he sees now as a good time to evaluate and safeguard existing programs rather than to throw money at new programs. "It's easy to create new ones, but we've got to see if what we've got makes a difference."

As an example, he points to a 1992 evaluation of the Minority Teacher Incentive Grant program that showed it simply wasn't serving African-American males as hoped. Proposed by Gov. Jim Edgar and approved by the General Assembly in July of 1991, the grant program awards scholarships of up to $5,000 a year to minority students who pursue degrees in education. It is administered by the Illinois Student Assistance Commission and requires recipients to

teach in Illinois schools one year for each year they receive the scholarship.

Though it was only a year old, the program was amended in July 1992 to remove a requirement that candidates be in the top 20 percent of their high school graduating classes. Instead, successful applicants simply must maintain good academic standing in college. Turner said this loosening of needed qualifications will help lure more African-American males into the field. "I know that's going to make a big difference."

Education experts say any effective assessment of existing programs should include some analysis of whether they are getting at the root of true barriers preventing many African-American students from attending college. Several point to a lack of positive role models throughout many African-American males' lives as one barrier, looking with optimism toward the amended Minority Teacher Incentive Grant program.

"The problem of African-American males has to do a lot with the nurturing and support they receive during their formative years," said Charles Morris, vice chancellor for academic affairs for the Board of Regents. Tendaji W. Ganges, director of Northern Illinois University's office of educational services and programs, agrees. Early in life, children need to see black males in successful, leadership positions — such as at the head of a classroom, he said. While the 1980s saw a particularly sharp drop in the number of African-American students receiving degrees in education, the number was back up in the early 1990s.

22/January 1993/Illinois Issues

Offering a student's perspective on the matter is Michelle Johnson, a senior at NIU and president of the university's Black Student Union. She says she's seen schools expend time and money successfully recruiting African-American students to college campuses and then virtually abandon them once they've enrolled. "I'm not saying they need someone holding their hand," said Johnson, 22, who is working toward a bachelor's degree in general studies. "But some of these students are the very first in their families to go away to school, and they could use some extra guidance, someone telling them realistically how many hours of classes to take, or reminding them of all the dates and deadlines for federal financial aid and state financial aid — and even for registration. I don't feel universities do enough to retain minority students."

According to the Illinois Board of Higher Education, 63 percent of the African-American students who entered an Illinois public university as freshmen during most of the 1980s did not graduate from and were not enrolled in that

university three years later. That compares to a dropout rate of 53 percent for Hispanic students and 37 percent for white students. It's difficult to know how many of these students transferred and wound up graduating from other schools, but educators say many likely dropped out.

That's not to say all the news was bad; indeed, African-American student enrollment in graduate and professional programs increased from 6.9 to 7.9 percent between 1980 and 1990. But school officials would like to see these numbers more accurately reflect minorities' percentages of the general population.

In fiscal year 1991, the Illinois Board of Higher Education recommended increases of $3.6 million for minority student and staff programs at public universities. That year's state appropriations, though, provided only limited increases: Inflationary funding was allocated by the state for a community college grant program and an additional $250,000 was appropriated for other projects. In fiscal year 1992, the board recommended $6 million in new funds for

minority student achievement, seeking to improve access at the collegiate level and improve preparation of elementary and secondary school students. But the 1992 state budget also had relatively little additional funding for higher education; $2.7 million actually was approved toward minority programs.

Whether the near future will hold a more generous track record for programs geared toward minorities — or whether minority education programs can even retain their current funding levels — will be up to the 88th General Assembly. It's hard to predict what priority those programs will be given among competing Chicago, suburban and downstate factions. But in the face of such varied interests, minority lawmakers probably are wise to concentrate their energy regarding this issue into avoidance of slipping backward. *

January 1993/Illinois Issues/23

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||