|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By DAVID H. EVERSON

Reapportionment, apportionment and redistricting

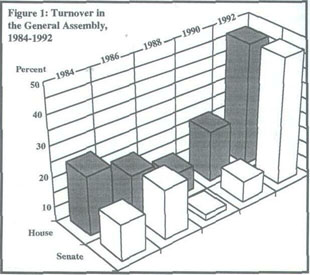

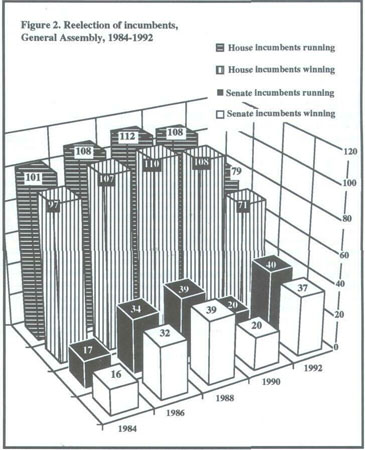

'Natural' term limits in Illinois A major story of the 1992 Illinois legislative elections is the significant degree of turnover they generated in the makeup of the General Assembly. Membership changed 42 percent in the House from the previous session and 43 percent in the Senate. These figures dwarf the session-to-session turnover of recent prior elections (see figure 1). The causes of so much change in the 1992 elections are clear: reapportionment, redistricting and the luck of the draw. Cumulative session-to-session turnover plus redistricting will always produce more turnover than many believe takes place in state legislatures. The results of the 1992 elections reinforce the conclusion that term limits might be largely redundant for Illinois lawmakers. Ideally, the elected membership of a state legislature represents a judicious mix of experienced legislators and fresh blood. Some stability in the membership is desirable since both parties need experienced lawmakers to provide their leaders and committee chairs or minority spokespersons. The legislature also needs experienced members to balance the knowledge and skills of veteran lobbyists and longtime executive bureaucrats. Stability also helps the legislature preserve sufficient institutional memory to recall what has been tried before and worked or failed (and why). Too much stability, however, can lead to the abuse of legislative power or to continual stalemate on major issues. In the best of all possible worlds, change in the composition of the legislature provides new energy and a catalyst for policy innovation. A word of caution on expectations for new Illinois lawmakers, however. When the same basic leadership is still in place and tightly controls both chambers, a large number of new members may not necessarily signal much innovation (for details on new rules to tighten leadership control of both chambers, see "Legislative Action" on page 26). The Illinois General Assembly generally does not offer the "best of all possible worlds." Illinois legislative elections have followed national trends in their extremely high incumbent reelection rates. In Illinois House races from 1984 to 1990, 429 incumbents ran in the general election and 418 were reelected (97 percent). Of 110 Senate incumbents running from 1984 through 1990, 107 won (97 percent). (See figure 2.) The probability of an Illinois solon running for reelection and winning has been almost as near to a sure bet as the odds that education will ask for more dollars in the state budget. In the four general elections before 1992, only 14 of 539 incumbents lost. Illinois legislative elections are not very competitive, either. While winners of eight House elections in 1992 were decided by fewer than 1,000 votes (one by only 34), Illinois legislative elections typically are not tightly contested. In 1992 of all 118 House races and 59 Senate races, only 25 (15 percent) were decided by 10 percentage points or less.

16/March 1993/Illinois Issues In Illinois, the normal product of high incumbent reelection rates and weak competition in legislative elections is low turnover in the membership of the General Assembly. Indeed, the session-to-session turnover in the House and Senate averaged 15 percent and 10 percent, respectively, from 1984 to 1990 (see figure 1). Elections, primary and general, are the major, but not the sole, mechanism for ending incumbents' legislative careers. Other factors include death and voluntary retirement (at times to run for another office). In recent years, however, incumbent reelection rates for the U.S. House and the state legislatures have soared, leading to skeptical scrutiny of the capacity of the elections plus "natural" turnover to achieve desired levels of change. The present popular alternative for achieving change is term limits for those serving in the U.S Congress and state legislatures. At first blush, the Illinois General Assembly's extremely high incumbent success rate, lack of electoral competitiveness and low session-to-session turnover would appear to be powerful arguments for legislative term limits in the Land of Lincoln. Illinois' term limits advocates have a point: Low turnover threatens the capacity of legislatures to respond creatively to policy problems. A kind of institutional gridlock can develop where the policy needs of the state are always held hostage to the demands of the next election. Gridlock can lead to halfway measures or to ignoring the problems altogether. For example, in the 1980s, two temporary state income tax hikes were enacted instead of dealing with the revenue problems of the state on a long-term basis. Some reformers, despairing of the ability of the electorate to enforce its own term limits, have called for mandatory limitations on legislative tenure. In 1990, three states — California, Colorado and Oklahoma — were the vanguard, adopting limits. In 1992, 14 states had some form of term limits on their statewide ballots, either for their state legislatures or their representatives in Congress or both. All were adopted. Illinois was not one of the states voting on the issue; a citizen initiative to set term limits for Illinois lawmakers failed to gather enough signatures to get on the ballot (as an amendment to the Constitution's Legislative Article). Term limitation in Illinois is probably far from dead as an issue because the rate of incumbent return remains high, and for the following reasons.

March 1993/Illinois Issues/17

My earlier article ("Term limits . . . ," Illinois Issues, April 1992) speculated that the 1991 reapportionment and redistricting would result in a "fruit basket upset," with large numbers of new members elected to the Illinois General Assembly in 1992. They were, yet the incumbents running for their House and Senate seats in 1992 were only slightly more vulnerable in the general election than in the previous four elections. Nevertheless, the actual degree of turnover was substantial since fewer incumbents decided to run. In the 1992 elections, 71 of 79 House incumbents who sought reelection were successful for a 90 percent success rate (see figure 1). Eight House incumbents lost in this one election compared to 14 who lost in the previous four. The eight who lost in 1992, however, include five in races where new districts forced incumbents to face incumbents, guaranteeing a loss of incumbents without gaining a new member. An "adjusted" rate for House incumbent success, excluding the incumbent versus incumbent races, is 96 percent (66 out of 69), nearly equal to the incumbent rate of return in the 1984 through 1990 elections. In the 1992 Senate elections, the incumbent success rate was 93 percent; 37 of 40 incumbents who sought reelection won. Although the incumbency rates were high, the actual degree of turnover in the Illinois House from 1990 to 1992 was substantial: 41.5 percent of House members seated in January 1993 were "new" compared to January 1991. The rate of turnover in the Senate was slightly higher, 43 percent. The main cause of the relatively high turnover following redistricting is that fewer incumbents ran for reelection. From 1984 through 1990, the number of House incumbents in the general election averaged 107 in the House. In 1992, 79 House incumbents were on the November ballot; 13 had lost in the primary. Another 15 House incumbents ran instead for a Senate seat, and 11 incumbents "retired." The upshot: four in ten members of the 1993 House are rookies. A similar process resulted in an even greater change in the makeup of the Senate, and the change in the Senate was undoubtedly influenced by the fact that the Republicans drew the map. After the previous redistricting a decade ago, the 1982 legislative elections for the Senate produced a 25 percent change in members from the previous session, substantial but less than the 42 percent in 1992. The results of the 10-year electoral process — four normal elections of 1984, 1986, 1988 and 1990 plus the "cleansing" election of 1992 following reapportionment and redistricting — are clear: a wholesale change in the composition of the Illinois House and Senate. Of the 118 House members who took office in January 1983 after the 1981 redistricting, only 33 (27 percent) remained after the 1992 elections. For the Senate for the 10-year cycle, 19 of its 59 members seated in January 1993 were senators in 1983, for a 68 percent turnover.

David H. Everson is professor of public affairs and political studies and holds a joint appointment in the Illinois Legislative Studies Center of Sangamon State University, Springfield. Jeff Stauter, graduate assistant in the center, provided research support for this article.

18/March 1993/Illinois Issues |

|

|