|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Illinois Issues Summer Book Section

By RICHARD PECK

Battered by Left and by Right

Censorship in the '90s as viewed by a novelist from Illinois whose books have wound up on forbidden lists

It's the opening day of school in New York City and an untried teacher's first day. Forty first-graders explode into her room. More than half of them speak no English. None of them has taken a seat. Some of them are hungry. Forty first-graders and the mother of one of them. She strides to the new teacher's desk with a printout from a religious cult to which the family belongs. This mother's child may not pledge allegiance to the flag or to anything else. Because of such pressure, in this public school classroom there can be no celebration or decoration for any holiday, national or religious. One reference to Halloween can cost this teacher her job or a lawsuit. This current event reminded me of teaching in a New York City junior high school 28 autumns ago. I arrived fresh from Illinois at a school on Park Avenue to find the English department in the process of banning a book. They were expunging it with maximum efficiency and without publicity by removing it from the reading lists and disposing of the class sets. I'd been counting on assigning that book. It was Harper Lee's novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. The reason for its

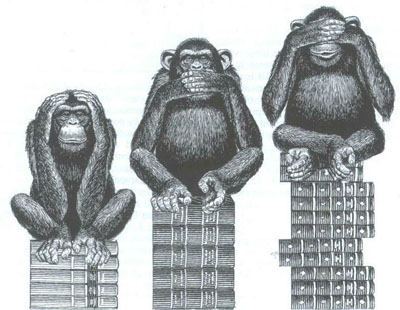

24/July 1993/Illinois Issues removal, to quote from the department minutes: that it "celebrates white, bourgeois values," the values, as far as I could see, of the people banning it. Alerted on the first day, I wasn't destined to have a long teaching life at that school. Instead, I became a writer of novels for young readers the same age as my former students. Over the 20 years since, the issue of censorship, at its most impassioned in school curricula and library youth services, has gone from the occasional lightning raid to a much more fully pitched and professionally organized battle that books and their defenders are currently losing. The path that has led us to 1990s censorship is long and tortuous and veers from Left to Right. Censorship begins, of course, at the writer's desk. Authors aren't nearly as uninhibited as their detractors aver. In books I write for the young I don't use their language or the words written on the walls of the schools I visit, the words very young children hear from television if not in their own homes, then elsewhere.

The very presence of books ignites parents and power groups whose children might thereby be exposed to ideas religiously or politically different from their own. Leanne Katz, director of the National Coalition Against Censorship, quotes a Florida parent appalled by her child's seventh-grade classroom. "It's just like walking into a bookstore with desks. There are books just lining the walls." Twenty-five years ago the diversity of inexpensive paperback books fostered an educational innovation, freeing classrooms from the lockstep of the old, over-priced literature anthology and allowing teachers to tailor the curriculum to their own students' needs. A current trend is the return of the anthology to placate parents darkly suspicious of classrooms that look like bookstores or libraries. But, predictably, even anthologies of the tried-and-true are under fire. In the New York Times Book Review Diane Ravitch reports, "In Tennessee, the Holt series was criticized for including The Wizard of Oz it allegedly teaches witchcraft and magic and Anne Frank's diary for allegedly suggesting that all religions are equally valid."

I found myself on a forbidden list when I wrote two stories lightly laced with the supernatural which were, in fact, comedies of manners set in my hometown, Decatur, Ill., back at the turn of the century. Walt Disney Productions filmed the first one The Ghost Belonged To Me with impunity. But then the titles found their way into Phyllis Schlafly's syndicated Copley News Service column. She warned her readers that my "books could lead children to believe that, in order to be an interesting person, one should try to contact the dead and seek acquaintances who do likewise." Thus the two most innocent books I've ever written continue to appear on the master lists circulated by watchdog organizations. One result was that when I was invited to speak at the grade school I'd long ago attended, the principal allowed members of a fundamentalist sect to monitor my presentation. Another result has been the kind of publicity that money won't buy and publishers won't budget for. If the entire fundamentalist membership heeded the call from their pulpits and handlers, we'd hardly have a library or a school program left. But the fundamentalist parents who act have their own profile. They tend to have children either just entering school or trembling on the brink of puberty, two moments when parents fear a sudden loss of control. Book censorship isn't about books; it comes of redirected parental fear. A noticeable number of their children aren't star students either, and when your child isn't achieving, a face-saver is to attack the book and the school. We would be much nearer nirvana now if parents respected schools more and feared their own children less. Censorship from the religious Right fires most of its rounds at elementary and middle schools in the attempt to

July 1993/Illinois Issues/25

transform these public institutions into tuition-free sectarian academies. Censorship from the Left trickles down to grades K through 12 from the theorizing reaches of academe and the dictates of professional as well as activist organizations, resulting in all those textbook instances of greening, outing, racial balancing, gender-neutralizing and social engineering recorded with such gusto by The National Review. The 1992 quincentennial was dominated by the politically correct viewpoint that Columbus had destroyed America instead of discovering it. "Multiculturalism" is the battle cry of the '90s, strong in its implication that America as melting pot diminished the racial and immigrant groups that enriched it. We're drawing near the edge of the abyss as books are increasingly judged less on their artistic merits and more by the race or ethnicity of their authors. And the liberals harry the individual word as keenly as the conservatives. Speakers at the annual convention of the National Council of Teachers of English are sternly warned in writing to eschew all sexist grammatical constructions, while the English-teaching establishment might better implement plans to teach the rudiments of language to their students and to ban the phrase "you know" from all classrooms. But adults of all viewpoints now find it easier to bully each other than to challenge their own children. This spring an English teacher discovered a parent in her classroom after school. "You are teaching my son James Hilton's Lost Horizon," this father said, "and I know what you're up to. You are teaching my son Buddhism, and I'm going to put a stop to you, one way or another." "Go to my principal and tell him what you've said to me," the teacher replied. Then she watched from her classroom window as the man left the school, less inclined to confront a male authority figure. She went to the principal to say that a parent was accusing her of teaching Buddhism. "Are you?" asked the principal, visibly disengaging. And so they will see that parent again. Like adolescents, censors will test any system but their own. And when they find weakness, they'll be back. Richard Peck received an MA in English from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, where he began his teaching in 1959. He has written 20 novels, and his next nonfiction title will be Love and Death at the Mall: Teaching and Writing for the Literate Young, forthcoming from Delacorte in the Spring of 1994.

Mike Cramer

26/July 1993/Illinois Issues |

|

|