|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By BEVERLEY SCOBELL

Coal is a dirty word

As Americans breathe cleaner air,

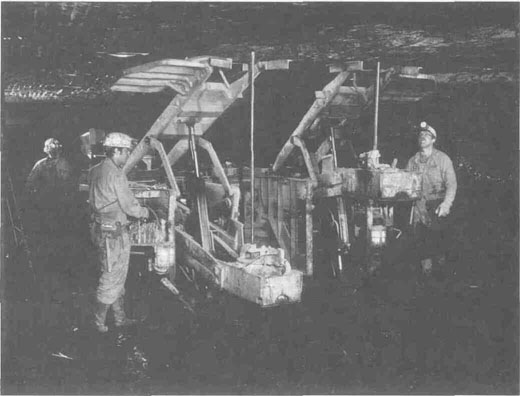

Photo courtesy Kerr-McGee Coal Corporation

The "black diamond" is losing its luster. Coal mining, which has been part of the economic and cultural fabric of southern Illinois almost as long as there has been a southern Illinois, is now causing painful change to many people in the region. They are the victims of the titantic clash between economic health and environmental quality. Their pain will intensify during the next decade with repercussions felt across the state as the struggle between "clean" air and "dirty" coal centers on Illinois, and particularly on southern Illinois. Half the coal miners in Illinois could lose their jobs in this last decade of the twentieth century as a result of the acid rain regulations in the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. The process has already begun in Saline County in southeastern Illinois, where Sahara Coal Company, which can trace its history to the earliest mining operations in the county, shut down, idling nearly 300 miners. Sahara lost its main customer, Electric Energy, Inc. at Joppa, Ill., which switched to lower sulfur Wyoming coal to comply with clean air mandates. Saline County may well offer a picture of the pain yet to come. This momentous change has roots in Washington, D.C., as well as in the deep underground seams of Illinois' most abundant fossil fuel. According to the Illinois State Geological Survey, Illinois has 48 counties each containing over a billion tons of coal resources. However, the high sulfur content of much of Illinois' coal makes it a target for the restrictions contained in the 1990 amendments to the federal Clean Air Act. As the first deadline for controlling sulfur dioxide emissions approaches in January 1995, utility companies,

November 1993/Illinois Issues/19

20/November 1993/Illinois Issues Sahara coal miners. Mike Vessell, labor market economist with the Department of Employment Security, says the lost mining jobs have sent the unemployment rate for the county to 16.6 percent for August compared to 7.3 percent for the state. Last May the rate was 12.2 percent for Saline County. Vessell predicts the rate will hit 18 percent, minimum, within the next 60 days when Peabody miners are added to the rolls. Vessell says the retail trade, particularly the "mom and pop" businesses, will be among the first to feel the effects of the drop in wages. On average, mining jobs pay more than double what other workers in Saline County make. Mayor John D. Cummins of Harrisburg fears a significant drop in sales tax revenues because "the unemployed miners will not have the disposable income they have been used to spending for such things as eating out, movies and shopping." Indeed, estimates run from $1 million to $2 million per month in lost payroll and lost revenues to businesses serving the closed mines or jobless miners. Walter K. Bean, mayor of Eldorado, echoes Cummins' apprehensions. Bean says people have been calling him worried about paying their county property taxes. He reports that county officials have considered allowing late payments, but that probably won't prevent some families from selling their houses and moving out of the community. Some families left, says Bean, after the surface mine. Equality Mining Company Mine No. 1, closed in December 1991, idling 47 employees. Moving away is considered a last resort by most of the unemployed miners, whose roots are as deep in southern Illinois as the seams of coal. Nevertheless, William H. McClusky, president of District 1 of the Progressive Mine Workers of America, the union representing the miners at Sahara Coal, says they are "scared to death." It is a shock, he says, to people who have worked hard all their lives and made good money — most, he says, averaged about $40,000 a year — to now realize they may not be able to afford to stay in their homes. "They tell me 'my house only lacks two years of being paid off, but the taxes are $2,000.' They'll end up losing it for that," says McClusky. The financial devastation reaches beyond the 300 laid-off miners, McClusky says. Another 250 retired miners and at least 1,200 family members are affected through lost medical benefits. For miners accustomed to almost 100 percent health coverage, including eyewear and dental care, the loss of insurance is almost as frightening as the loss of good wages, says McClusky. "Hillary is going to save us," McClusky says half sarcastically and half hopefully. For everyone agrees that some of the families out of work will be forced to turn to government assistance in order to survive. Yet, that choice will not come easy to many of the unemployed miners. Southern Illinois is a rough-hewn sort of place, a socially conservative region with a culture that values and encourages personal independence and self-reliance. Rep. David Phelps (D-118, Eldorado) says that determination to support one's family by whatever means necessary may cause some families to "drop through the cracks" of the state welfare system. Phelps says he's seen husbands accept any kind of odd jobs to feed their families, and wives who have never worked outside the home seek jobs. Those jobs tend to be in the service industry, the only employment available besides farming and mining, and usually are part-time, minimum wage and without benefits. Those with low-wage full-time employment are even more vulnerable. "These people are not going to be able to qualify for public aid because the wife is a clerk in the bank, a secretary or a real estate broker, and the husband is picking up odd jobs," says Phelps. "If something happens, the hospitals are going to be absorbing a lot of big bills, and that has a ripple effect of those who are paying will have to pay more." Moreover, local officials harbor the fear that a cycle of decline for support of public schools and small businesses — the heart and lifeblood of most small communities — has begun and may be irreversible in the near future. Sahara's property taxes of nearly $150,000 a year, of which about half went to the local school system, will be substantially cut as the taxes drop on the idle land. John Hill, superintendent for Harrisburg Community Unit School District 3, says the mine closings will definitely hurt the school district. "I am certainly anticipating a decline in our student enrollment, maybe five to 10 percent," says Hill. That may mean the school district will have to lay off staff in the next school year, he says. With the school district already on the State Board of Education's financial watch list. Hill says that "there's nothing good that can happen to the school district out of this."

Even so, the area has taken steps to market itself for new business. Route 13, the main linkup to the interstate system, is being widened to a four-lane highway for easier access to mar-

November 1993/Illinois Issues/21

What is happening in Saline County may be a glimpse into the future of coal mining. Even as Sahara shut down, AMAX Coal Industries, Inc. operates a mine of the same size, in the same area, producing an identical product. "Sahara's gone, and AMAX is still producing," says Mines and Minerals Director Morse. AMAX is a multinational corporation with low-sulfur coal reserves in both West Virginia and the Powder River Basin in Wyoming. Because the large mining corporations have diverse operations, says Morse, they can shift resources and can blend high-sulfur, high-Btu Midwestern coal with low-sulfur, low-Btu western coal to reach a mix that complies with federal regulations. Saline County has three other coal mines operating: Big Ridge, owned by Arclar Coal Company, an independent, family-owned producer confined to the county; Brushy Creek, owned by Western Fuels Corporation; and Galatia Mine, owned and operated by Kerr-McGee Corporation, a multinational, diverse-fuel company based in Oklahoma City, Okla. Both Morse and Taylor Pensoneau, vice president of the Illinois Coal Association, agree that economic forces point to a restructuring of the coal industry that could result in small independent companies going out of business, threatening two more mines and another 370 mining jobs in Saline County. The jobs at the Galatia mine seem to be secure, at least through the first phase of the Clean Air Act restrictions limiting sulfur dioxide emissions. According to the Illinois Department of Energy and Natural Resources, less than 10 percent of Illinois coal reserves can meet the 1995 standards. Galatia Mine in Saline County is one of the four mines in Illinois that currently mine low-sulfur coal. But, says Kirn Underwood, director of the state office of coal development and marketing, "There's not an ounce of Illinois coal that can meet the stricter Phase II standards" that will take effect on January 1, 2000. Morse says that all of Wyoming's Powder River Basin coal, Illinois' chief competition, has sulfur levels below Phase II standards. "However," says Morse, "it takes three trainloads of western coal to reach the heat level of one trainload of Illinois coal." On the other hand, Morse says, western coal is found in 60-foot seams just 6 feet underground, whereas Illinois coal is in a 6-foot seam 600 feet underground. Kerr-McGee officials believe they will be able to weather effects of the federal regulations until either the market for Illinois coal improves or technology reaches the point of making the problem of sulfur dioxide emissions moot. New markets for medium- and high-sulfur coals are expected to develop in the next twenty years. State officials expect domestic markets to develop with the installation of sulfur dioxide control technologies at existing power plants and the construction of new plants incorporating technology to burn high-sulfur coal. As worldwide energy needs increase, export markets are expected to grow. In addition, as a leader in clean coal technology, Illinois expects growth in energy-related businesses, which should bring new engineering and manufacturing jobs to Illinois. None of which offers much solace to miners in Saline County and throughout southern Illinois. Around Christmas time, unemployment insurance will run out for many of the Sahara miners. The Eagle No. 2 miners will not be far behind, as will thousands more across the coal producing region of southern Illinois, if all predictions come true. Those whose lives depend on coal are likely to pay a higher price than most Americans to breathe clean air.*

22/November 1993/Illinois Issues |

|

|