DEFINING REGIONS:

A TEACHING STRATEGY

|

Overview

Main Ideas

One of the most stimulating activities for

students is for them to create their own

maps and then to try to decide what those

maps mean. There is the fun of watching

geographical patterns emerge, and there is

the intellectual challenge of explaining these

patterns. The concept of region is

explained, and material is provided so that

students can create their own regions.

There are no right or wrong answers. The

success of the exercise must be measured

by the extent to which it stimulates debate

on regions, discussion of cause and effect,

and interest in Illinois history.

The "historic present" is a useful

method by which geography and history can

be combined in the classroom. To discover

the unique character of an area — in this

case Illinois — at a particular time — in this

case 1870 — one needs some basic facts,

a willingness to think in terms of what was

really important to people at that period, and

a little imagination. Here are some of the

things that might be important in interpreting

the maps that the students will create.

Illinois is basically a flat state (see Figure1);

there are only four fairly small areas where

bedrock dominates, and most of that land is

too rocky and hilly for much farming: the

Galena country in the northwest, the Lincoln

Hills in Calhoun and southern Pike County,

the Salem Plateau in the southwest, and the

Shawnee Hills in the far south.

Illinois was settled by quite different

groups. Upland Southerners came from

Kentucky and Tennessee and moved north,

while settlers from the eastern states came

somewhat later and generally moved from

east to west. Of the last group, the New

Englanders who settled the northernmost

counties of the state were perhaps the most

different from the Upland Southerners.

48

Until a few years before 1870 you

could not farm until you put up a fence to

keep out the neighbors' livestock, which did

not have to be fenced in; this meant that

trees for fences were essential for settlement, and it helps to explain why the last

area in Illinois to be settled was the treeless

Grand Prairie. Substantial parts of that zone

had yet to be occupied in 1870. Many of the

larger river valleys in Illinois are lined with

rocky cliffs or swampy lowlands, which presented problems for farmers. Growing seasons in Illinois become shorter as one goes

north, which in turn influenced the selection

of crops. Corn was already the biggest

money-making crop in Illinois in 1870, and

huge amounts were being shipped to other

states and countries. However, almost all

farm work was done with the aid of horses,

requiring farmers everywhere in Illinois to

devote a large number of acres to oats to

feed their work animals. The railroad network was making rapid progress in Illinois,

but many areas were not yet served.

Chicago had grown extremely rapidly

between 1850 and 1870, and in 1870.

Chicago was the only really large city in the

state. In 1870 most people in Illinois lived

on farms, and except perhaps in Cook

County, population changes between 1860

and 1870 depended on changes in farming.

Remember too, that the southern part of the

state was settled first, so those counties

generally had less room for new farms than

did those in the north.

Connection with the Curriculum

Focusing on the region can facilitate an

emphasis on higher level thinking. Students

must process a great deal of information in

the analysis of a variety of topics. Synthesis

occurs when they attempt to understand the

interrelationships of those topics and arrive

at composite pictures of unique regions.

Employing the temporal dimension of history and the spatial dimension of geography

offers a powerful combination by which students can understand a part of their world.

Teaching Level

Grades 7-12

Materials for Each Student

• U.S. outline map

• 1870 data

• Illinois base map (with counties

labeled)

• Illinois physiographic map

• Colored pencils or markers (optional)

49

Identification of data categories:

- Population per square mile

- % population growth, 1860-1870

- % area in improved land

- % woodland

- % farms of 100 or more acres

- % farms of fewer than 50 acres

- % of total crop production in corn.

(Note: Oats dominant in Boone, Cook, DeKalb,

Du Page, Kane, Kankakee, Lake, and Will. Wheat

dominant in Jersey, Monroe, Randolph, and

St. Clair.)

- $ value of market gardening per square mile

- $ value of orchard products per square mile

- Number of milk cows per square mile

- Number of cattle per square mile (excluding milk

cows and oxen)

- Number of swine per square mile

|

1870 Data

|

|

County

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

|

Adams

|

66

|

36

|

55

|

21

|

24

|

40

|

45

|

57

|

200

|

13

|

19

|

66

|

|

Alexander

|

45

|

124

|

9

|

12

|

15

|

43

|

79

|

8

|

23

|

2

|

3

|

21

|

|

Bond

|

35

|

34

|

60

|

18

|

35

|

30

|

56

|

1

|

105

|

10

|

13

|

45

|

|

Boone

|

46

|

34

|

76

|

17

|

41

|

23

|

34

|

1

|

82

|

25

|

28

|

28

|

|

Brown

|

40

|

23

|

29

|

48

|

22

|

44

|

62

|

3

|

19

|

7

|

16

|

53

|

|

Bureau

|

37

|

22

|

72

|

8

|

46

|

17

|

65

|

3

|

68

|

16

|

33

|

58

|

|

Calhoun

|

26

|

27

|

24

|

40

|

14

|

64

|

49

|

6

|

126

|

7

|

9

|

44

|

|

Carroll

|

38

|

40

|

66

|

10

|

45

|

23

|

50

|

3

|

44

|

18

|

33

|

59

|

|

Cass

|

31

|

2

|

39

|

14

|

50

|

20

|

79

|

0

|

6

|

6

|

17

|

34

|

|

Champaign

|

33

|

123

|

66

|

3

|

29

|

39

|

79

|

5

|

42

|

9

|

18

|

36

|

|

Christian

|

29

|

94

|

53

|

4

|

47

|

18

|

67

|

1

|

45

|

6

|

11

|

49

|

|

Clark

|

37

|

25

|

37

|

31

|

21

|

47

|

59

|

10

|

89

|

8

|

14

|

37

|

|

Clay

|

34

|

70

|

49

|

27

|

25

|

47

|

74

|

8

|

69

|

8

|

13

|

43

|

|

Clinton

|

35

|

48

|

49

|

16

|

33

|

26

|

43

|

6

|

87

|

8

|

9

|

38

|

|

Coles

|

50

|

78

|

64

|

14

|

27

|

46

|

81

|

2

|

56

|

11

|

22

|

66

|

|

Cook

|

365

|

141

|

57

|

3

|

38

|

31

|

24

|

156

|

20

|

24

|

15

|

16

|

|

Grawford

|

31

|

20

|

37

|

27

|

25

|

38

|

61

|

0

|

57

|

7

|

10

|

44

|

|

Cumberland

|

35

|

47

|

34

|

18

|

29

|

31

|

59

|

1

|

32

|

7

|

10

|

29

|

|

DeKalb

|

37

|

22

|

85

|

4

|

59

|

9

|

36

|

4

|

16

|

23

|

29

|

42

|

|

DeWitt

|

37

|

36

|

66

|

12

|

35

|

32

|

79

|

48

|

83

|

11

|

19

|

74

|

|

Douglas

|

32

|

88

|

55

|

4

|

40

|

28

|

84

|

1

|

44

|

8

|

28

|

42

|

|

Du Page

|

50

|

13

|

76

|

8

|

53

|

15

|

24

|

22

|

63

|

32

|

23

|

25

|

|

Edgar

|

34

|

27

|

67

|

17

|

32

|

46

|

78

|

0

|

98

|

11

|

33

|

62

|

|

Edwards

|

34

|

39

|

41

|

40

|

25

|

29

|

58

|

1

|

38

|

9

|

13

|

60

|

|

Effingham

|

33

|

100

|

39

|

18

|

21

|

47

|

51

|

0

|

74

|

9

|

11

|

36

|

|

Fayette

|

28

|

75

|

41

|

20

|

23

|

47

|

52

|

2

|

105

|

9

|

11

|

34

|

|

Ford

|

19

|

359

|

45

|

1

|

39

|

19

|

73

|

2

|

2

|

6

|

12

|

20

|

|

Franklin

|

31

|

34

|

30

|

2

|

13

|

64

|

66

|

20

|

90

|

8

|

14

|

62

|

|

Fulton

|

44

|

14

|

41

|

22

|

32

|

31

|

65

|

1

|

92

|

10

|

18

|

67

|

|

Gallatin

|

35

|

38

|

24

|

33

|

7

|

71

|

82

|

2

|

3

|

6

|

7

|

46

|

|

Greene

|

37

|

25

|

50

|

27

|

32

|

40

|

62

|

2

|

50

|

8

|

24

|

58

|

|

Grundy

|

35

|

44

|

72

|

2

|

48

|

8

|

50

|

3

|

7

|

16

|

30

|

20

|

|

Hamilton

|

30

|

31

|

32

|

34

|

8

|

66

|

70

|

2

|

110

|

8

|

9

|

57

|

|

Hancock

|

45

|

24

|

61

|

21

|

32

|

29

|

57

|

5

|

85

|

12

|

21

|

56

|

|

Hardin

|

28

|

36

|

24

|

39

|

12

|

65

|

74

|

0

|

2

|

6

|

8

|

45

|

|

Henderson

|

34

|

32

|

59

|

15

|

39

|

22

|

75

|

41

|

131

|

12

|

23

|

74

|

|

Henry

|

43

|

72

|

50

|

5

|

43

|

14

|

67

|

0

|

19

|

11

|

19

|

42

|

|

Iroquois

|

23

|

109

|

45

|

8

|

36

|

28

|

60

|

2

|

8

|

9

|

19

|

19

|

|

Jackson

|

33

|

105

|

21

|

23

|

8

|

68

|

56

|

6

|

113

|

5

|

7

|

45

|

|

Jasper

|

23

|

34

|

29

|

21

|

19

|

51

|

65

|

0

|

18

|

6

|

10

|

25

|

|

Jefferson

|

31

|

38

|

33

|

26

|

19

|

55

|

69

|

6

|

55

|

7

|

11

|

44

|

|

Jersey

|

40

|

25

|

39

|

22

|

34

|

33

|

45

|

1

|

98

|

8

|

21

|

43

|

|

Jo Daviess

|

46

|

2

|

41

|

21

|

26

|

35

|

52

|

11

|

79

|

17

|

30

|

57

|

50

|

County

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

|

Johnson

|

33

|

20

|

26

|

-

|

10

|

63

|

67

|

0

|

126

|

5

|

5

|

40

|

|

Kane

|

75

|

30

|

72

|

10

|

56

|

18

|

37

|

7

|

44

|

31

|

25

|

29

|

|

Kankakee

|

36

|

58

|

72

|

3

|

41

|

23

|

41

|

4

|

9

|

18

|

25

|

24

|

|

Kendall

|

39

|

-5

|

80

|

7

|

55

|

10

|

54

|

1

|

58

|

19

|

27

|

46

|

|

Knox

|

55

|

38

|

72

|

7

|

41

|

26

|

69

|

5

|

94

|

15

|

33

|

86

|

|

Lake

|

46

|

15

|

72

|

7

|

41

|

24

|

36

|

12

|

59

|

27

|

24

|

29

|

|

LaSalle

|

61

|

26

|

73

|

7

|

47

|

11

|

62

|

8

|

38

|

15

|

26

|

32

|

|

Lawrence

|

34

|

36

|

26

|

21

|

23

|

39

|

62

|

0

|

46

|

8

|

13

|

47

|

|

Lee

|

37

|

54

|

69

|

3

|

41

|

17

|

52

|

14

|

24

|

18

|

27

|

35

|

|

Livingston

|

30

|

170

|

56

|

2

|

39

|

16

|

59

|

1

|

4

|

10

|

14

|

27

|

|

Logan

|

37

|

62

|

81

|

7

|

42

|

22

|

84

|

5

|

43

|

10

|

9

|

77

|

|

Macon

|

46

|

93

|

55

|

5

|

41

|

20

|

75

|

8

|

43

|

9

|

14

|

51

|

|

Macoupin

|

38

|

33

|

53

|

15

|

44

|

23

|

44

|

3

|

40

|

8

|

14

|

37

|

|

Madison

|

61

|

41

|

55

|

19

|

26

|

39

|

56

|

96

|

99

|

11

|

8

|

72

|

|

Marion

|

36

|

62

|

37

|

13

|

.25

|

49

|

64

|

3

|

101

|

8

|

12

|

38

|

|

Marshall

|

44

|

26

|

67

|

11

|

35

|

25

|

68

|

14

|

75

|

14

|

18

|

52

|

|

Mason

|

30

|

48

|

61

|

9

|

48

|

24

|

83

|

3

|

44

|

8

|

11

|

31

|

|

Massac

|

40

|

54

|

16

|

22

|

13

|

35

|

58

|

3

|

38

|

4

|

4

|

23

|

|

McDonough

|

45

|

32

|

69

|

19

|

38

|

19

|

68

|

3

|

74

|

12

|

24

|

70

|

|

McHenry

|

39

|

7

|

59

|

6

|

36

|

30

|

44

|

17

|

42

|

27

|

24

|

35

|

|

McLean

|

46

|

88

|

67

|

5

|

47

|

16

|

75

|

10

|

45

|

10

|

23

|

52

|

|

Menard

|

37

|

22

|

67

|

17

|

37

|

34

|

86

|

0

|

71

|

11

|

32

|

86

|

|

Mercer

|

34

|

25

|

63

|

13

|

47

|

22

|

72

|

2

|

61

|

14

|

28

|

75

|

|

Monroe

|

33

|

2

|

37

|

34

|

14

|

46

|

40

|

5

|

43

|

7

|

4

|

34

|

|

Montgomery

|

36

|

83

|

61

|

11

|

31

|

40

|

52

|

6

|

58

|

9

|

11

|

49

|

|

Morgan

|

50

|

29

|

81

|

17

|

42

|

34

|

85

|

41

|

74

|

10

|

53

|

78

|

|

Moultrie

|

32

|

62

|

69

|

12

|

26

|

44

|

78

|

2

|

133

|

10

|

20

|

69

|

|

Ogle

|

36

|

20

|

65

|

9

|

56

|

11

|

61

|

9

|

27

|

17

|

29

|

44

|

|

Peoria

|

77

|

25

|

43

|

12

|

34

|

28

|

63

|

31

|

46

|

10

|

15

|

57

|

|

Perry

|

31

|

44

|

30

|

24

|

20

|

52

|

34

|

2

|

46

|

7

|

8

|

33

|

|

Piatt

|

25

|

78

|

34

|

2

|

50

|

19

|

83

|

0

|

20

|

5

|

12

|

29

|

|

Pike

|

37

|

13

|

44

|

24

|

25

|

42

|

53

|

3

|

34

|

9

|

15

|

62

|

|

Pope

|

31

|

70

|

23

|

37

|

11

|

60

|

69

|

8

|

79

|

5

|

7

|

34

|

|

Pulaski

|

43

|

121

|

9

|

6

|

7

|

72

|

76

|

108

|

140

|

4

|

7

|

28

|

|

Putnam

|

39

|

12

|

31

|

14

|

47

|

25

|

72

|

34

|

72

|

9

|

18

|

34

|

|

Randolph

|

36

|

21

|

38

|

43

|

18

|

46

|

26

|

2

|

112

|

8

|

9

|

42

|

|

Richland

|

36

|

32

|

33

|

18

|

26

|

38

|

57

|

3

|

24

|

8

|

11

|

34

|

|

Rock Island

|

70

|

42

|

57

|

12

|

32

|

33

|

71

|

39

|

163

|

18

|

30

|

63

|

|

Saline

|

33

|

36

|

29

|

29

|

8

|

74

|

78

|

2

|

9

|

8

|

9

|

53

|

|

Sangamon

|

54

|

43

|

76

|

9

|

44

|

29

|

85

|

32

|

95

|

10

|

30

|

88

|

|

Schuyler

|

40

|

19

|

34

|

22

|

21

|

40

|

55

|

0

|

73

|

10

|

19

|

54

|

|

Scott

|

42

|

16

|

53

|

28

|

37

|

35

|

73

|

3

|

35

|

9

|

24

|

69

|

|

Shelby

|

34

|

74

|

65

|

16

|

31

|

40

|

65

|

0

|

34

|

10

|

14

|

58

|

|

Stark

|

37

|

19

|

75

|

7

|

44

|

13

|

71

|

0

|

51

|

14

|

26

|

92

|

|

St. Clair

|

76

|

35

|

54

|

18

|

27

|

33

|

40

|

139

|

85

|

9

|

7

|

44

|

|

Stephenson

|

54

|

21

|

71

|

12

|

39

|

21

|

47

|

4

|

42

|

19

|

27

|

61

|

|

Tazewell

|

43

|

30

|

55

|

11

|

40

|

22

|

72

|

21

|

118

|

10

|

17

|

53

|

|

Union

|

40

|

47

|

29

|

31

|

7

|

77

|

69

|

59

|

363

|

7

|

10

|

61

|

|

Vermilion

|

34

|

90

|

63

|

9

|

26

|

51

|

78

|

3

|

64

|

11

|

26

|

58

|

|

Wabash

|

39

|

20

|

38

|

26

|

18

|

34

|

57

|

0

|

10

|

8

|

10

|

46

|

|

Warren

|

43

|

26

|

77

|

8

|

41

|

17

|

77

|

5

|

82

|

15

|

31

|

96

|

|

Washington

|

31

|

28

|

49

|

16

|

44

|

22

|

41

|

10

|

130

|

7

|

8

|

37

|

|

Wayne

|

28

|

61

|

32

|

32

|

12

|

63

|

67

|

1

|

134

|

8

|

13

|

55

|

|

White

|

34

|

36

|

29

|

25

|

11

|

58

|

74

|

0

|

54

|

7

|

8

|

50

|

|

Whiteside

|

40

|

47

|

66

|

5

|

46

|

19

|

60

|

2

|

57

|

19

|

32

|

55

|

|

Will

|

51

|

47

|

78

|

4

|

51

|

16

|

35

|

5

|

41

|

22

|

29

|

25

|

|

Williamson

|

41

|

42

|

47

|

43

|

9

|

60

|

65

|

1

|

56

|

9

|

12

|

71

|

|

Winnebago

|

57

|

20

|

73

|

11

|

46

|

19

|

45

|

38

|

92

|

2

|

31

|

38

|

|

Woodford

|

36

|

43

|

67

|

7

|

38

|

15

|

66

|

2

|

89

|

12

|

20

|

83

|

51

Objectives for Each Student

The student will:

• Draw the approximate boundaries of

the Midwest region on a U.S. base

map and list those phenomena that

most significantly influence the

boundaries.

• Map one category of data provided for

Illinois in 1870 using recommended

procedures.

• Using the maps they have already

produced, establish, map, and justify

in writing the agricultural regions of

Illinois in 1870.

SUGGESTIONS FOR

TEACHING THE LESSON

|

Opening the Lesson

• Begin the lesson by asking students to

identify the characteristics that they

associate with some region with which

they are familiar. For example, Where

is the South? The Great Plains? The

Middle East? What are the characteristics of the region? How is it distinguishable from surrounding regions?

How can you tell when you are entering or leaving the region?

• Distribute outline maps of the United

States and ask students to list primary

characteristics of and draw boundaries around what they consider to be

the Midwest, first individually, then in

small groups of three or four. Display

the maps for inspection. Students will

probably find they generally agree on

a certain core of states, but disagree

about areas on the margins. Their

experiences will be similar in the following exercise on Illinois agricultural

regions in 1870.

Developing the Lesson

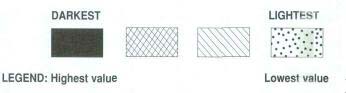

Assign to each student a category of

data to map. An equal number of counties

can be placed in each of four categories, or

four categories can be determined by an

equal range of data values. Students then

create maps by shading appropriate counties, using a uniform shading scheme so

that maps can be compared. Highest values

on the completed maps should jump out at

the viewer. For example, fully shade the

highest value, use crosshatching for the

second, diagonal lines for the third, and

small dots for the lowest category. Colors

enliven maps, but too many bright colors

are distracting.

Colors selected must reveal the range

of highest to lowest values at a glance.

Such maps are called choropleth maps, and

they are critical tools for geographers. This

mapping stage is fairly time consuming, but

it can be done as homework, and teachers

will find that in the process of mapping students will learn a great deal about the geography of Illinois. Mapping programs on computers can do this rapidly.

Each student-produced map should

contain TODALSIGS, the elements of good

mapmaking: T = title, 0 = orientation (minimum of a North arrow), D = date, A =

author, L = legend, S = scale, I = index, G =

grid, and S = source. Index is not necessary

in this exercise, and grid (latitude and longitude) can be noted along the map's margins

to avoid clutter.

When the maps are completed, tape

them to a wall or chalkboard, and give students a chance to examine the patterns

illustrated. Then ask students to look for

relationships by identifying areas where

several patterns correspond. Are areas

where corn dominates also those that have

little woodland and have experienced rapid

population growth? Does farm size differ

from north to south? Why? Do the areas

settled at an early date differ from those settled later?

52

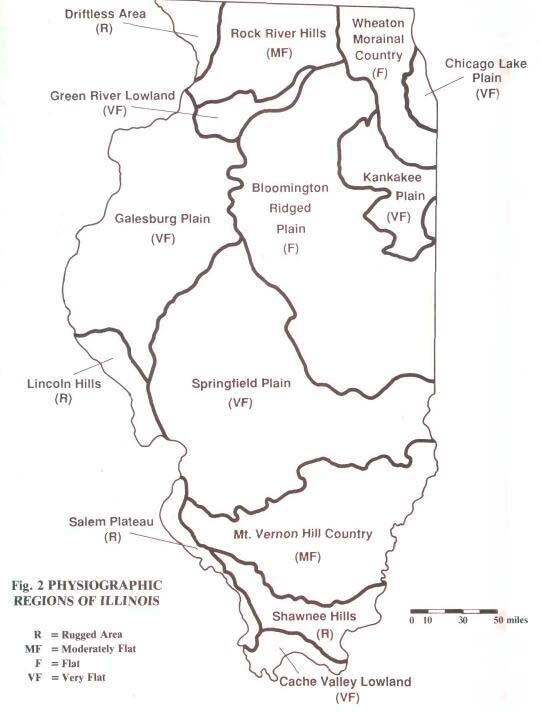

Distribute to each student a copy of the

Illinois Physiographic Regions map and

briefly describe the categories it displays.

Ask students: How do their maps correspond with the map of physical regions?

What does the information tell about the

relationship between farmers and the environment? What advantages or disadvantages were posed by location and the environment? How were the disadvantages

overcome? How does your particular county

fit into the overall pattern? Is your county

similar to or dissimilar from its neighbors?

Do not fall into the trap of thinking that

physiographic regions must correspond with

agricultural regions in any exact way.

Once students have explored those

questions, arrange students in groups of

three or four, and instruct each group to create its own overall map, which will be titled

Agricultural Regions of Illinois in 1870. Five

to eight regions of varying sizes should be

identified. Each should have its own

descriptive name, should consist of several

characteristics that seem to belong together,

and be accompanied by a written defense.

Tape the completed maps to the chalkboard

for inspection.

Concluding the Lesson

Lead a discussion of students' ideas

about Illinois regions. What are the merits of

the various maps produced? What problems

were encountered? How were they

resolved? Can the class agree on one

regional classification system? Could similar

techniques be used to create regions for

larger areas of the world?

Extending the Lesson

The answers to these questions could

provide the basis for greater in-depth studies, either for individuals or for the class.

Students could be asked to assume the

roles of young men or women sent west to

look for new farms to purchase in 1870.

After traveling the state, they must write letters to their families explaining what they

have seen in various parts of the state and

why they are recommending particular

places for new homes.

Assessing Student Learning

Choropleth maps can be collected for a

grade, but the agricultural regions maps and

accompanying rationales are better for the

purpose of evaluating students' understanding of the concept region. Subjective observations of students working in groups on

agricultural regions may also provide insight

to student understanding.

53

54

Click Here to return to the Article

55

|