|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

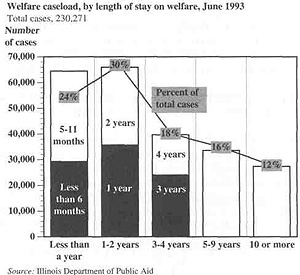

points to the politically unsettling conclusion that limiting welfare

rigidly to two years for everybody will cut off the path to success

Three years ago Karen Dare decided she'd had it just sitting at home collecting a welfare check. Twenty-four years old and a high school dropout, Dare decided to do something with her life. She enrolled in a high school equivalency class at John A. Logan Community College, situated between Marion and Carbondale in deep southern Illinois. Her prospects may have seemed bleak, even to her. She had already flunked the GED exam four times. And her own confidence was weak; "I was scared every morning just to get up," she recalls.

But watching her twin boys, then age seven, and her four-year-old daughter growing up emboldened her sense of purpose. "Mainly, I wanted to do this for my kids," she says. "I didn't want my kids growing up thinking that being on welfare was the way to do it. I wanted my kids to be proud of me."

So it will be with special pride that Karen Dare will cross the stage at the John A. Logan graduation ceremonies next month to get her associate's degree. Come fall, Dare expects to trade her welfare check for a paycheck when her apprenticeship as a dental assistant comes to an end and she takes on a full-time job.

"She's our success story," beams Jane Minton, the coordinator of John A. Logan's welfare-to-work programs. Minton is like an all-purpose mother hen who watches over her brood of students. Karen Dare's success story shows that with gumption, grit, lots of help, some luck and people who believe in them, people can go from welfare to work.

There is a way out of welfare. Dare's success story contains many lessons for welfare reformers who, as President Clinton has vowed, are trying "to end welfare as we know it." Chief among those lessons is that education and training can work — indeed, are vital — to make a person marketable in an economy that has become punishing for the uneducated and unskilled. It also demonstrates the need for a variety of financial supports, such as child care and transportation, that help welfare recipients survive. It shows the importance of "human supports" as well: the encouragement, the nurturing, and the assistance of someone who can untangle red tape, find child care, locate a doctor willing to accept a Medicaid card, type an English paper on deadline; someone who can help pick them up and cheer them on.

|

About this article

This is the second of a two-part series on welfare issues in Illinois. The first article was published in our February 1994 issue.

Journalist Donald Sevener spent several This series is made possible by a grant from the Woods Fund of Chicago. |

Dare's story and those of others show that the journey out of welfare is not a giant leap, but a series of small steps. One sure step is education — from basic academic skills like reading and arithmetic to basic job survival skills like punctuality and following directions. Another useful step often is employment: part-time jobs or low-pay entry-level positions that give welfare recipients a feel for the world of work and an appreciation for the importance of education and advanced training. Another crucial step is job training — teaching a vocation such as computer programming or a professional career like nursing. But those who have made it off welfare, and those who have helped them, agree that there is another, seminal, and somewhat intangible step that makes the whole journey possible — the ability to say, with conviction and confidence: I can make it. It is this "over-the-hump" step that begins the journey and so often interrupts it. Mainly, the successes of people like Karen Dare show that the path from welfare to work is usually a long one, filled with detours and roadblocks, triumphs and setbacks, steps forward and back and forward again, one difficult step at a time. |

When presidential candidate Bill Clinton pledged to "end welfare as we know it," he couldn't have had people like Karen Dare in mind. Clinton joined a rising chorus of politicians who say welfare recipients should be forced to earn their keep and that, no matter what, two years and a day on welfare would be a day too long.

If that proposal were policy, it would have stopped Karen Dare's journey out of welfare dead in its tracks. A two-year limit on moving from welfare to employment is not only arbitrary. It won't work.

28/April 1994/Illinois Issues

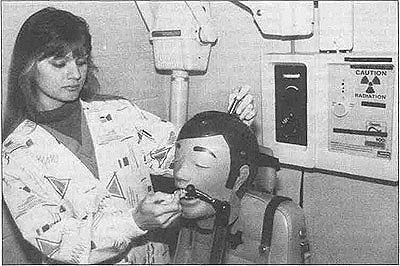

Karen Dare practices x-ray techniques on "Dexter" at the John A. Logan Community College dental lab. She plans to intern with her own dentist in Benton after graduation from the college's dental assistant program next month. Photo by Phil Pearson |

Dare's journey has been neither quick nor easy — nor is it necessarily over. It's been three years from beginning her GED classes to getting her associate's degree. "It was a slow process to get used to John A.," she says of the college that has 5,000 students on its sprawling campus across the street from the Crab Orchard Wildlife Refuge. It took her eight months to get her GED, a signal accomplishment that gave her the first sweet taste of success. 'That made me feel important," she says. "I thought: Yes, I did it." With that step behind her, she took another — a big one. She enrolled in college, where she found new obstacles. Treatments for a mild form of cancer couldn't keep her from attending class, nor could a gimpy car that she needed for the 40-mile round trip to school from her home in Orient, a village north of the college in Franklin County. Her family was supportive, but not her boyfriend, who didn't think she needed to go to college, nor that she was |

Others helped out, especially those at the college who operate a variety of classes, programs and services to help welfare recipients get the education and training they need to find jobs. "It helps a lot," says Dare, "when you've got someone who cares." Gradually, the tears evaporated, as did the fears of failure. Now she bubbles with confidence and with goals: "I want to work for awhile first, but I'm thinking of going to SIU to become a dental hygienist. Before, I was so down on myself I didn't know I could do it. Now, I know I can."

But it took a while for Dare to reach that realization. For many, the realization is a long time coming.

"I want you to break your life up into thirds," Kelly Christenson tells her class, "and then write down three successes you've had in each third of your life. This is a way to help you feel better." Dutifully, 22 students take pen in hand and follow her directions. One woman, seated in the back row, writes "married" under one of the columns on her paper, and "divorced" under another. She has trouble thinking of three successes during the last third of her life.

This is a job skills class at John A. Logan, aimed at giving students specific abilities they need — how to write a resume, how to act during a job interview — to find employment. It is also what some critics deride as a "self-esteem" class, designed less to teach useful skills than to make students feel good about themselves. But, says Jane Minton, next to transportation, low self-esteem is the biggest barrier most welfare recipients face. "I don't know anybody on welfare who doesn't have a problem with self-esteem," says Minton, including Karen Dare whose present can-do spirit is in stark contrast to the low opinion she held of herself and her prospects when she first enrolled at John A. Logan.

It is with that in mind that Christenson has begun her class with discussion of lessons from a videotape the students have watched: heal your negative past, affirm your strengths, acknowledge your successes, visualize goals, persevere.

"Now," Christenson tells the class, "I want you to think five years into the future, and write down three successes you'd like to accomplish."

The woman in the back row writes:

• "steady job"

• "to be in school"

• "to help my son graduate."

Most of the class want the same things. "Own a home," says one. "Get a job with good benefits," says another. "Get an education to have a better life for my children and myself," says a twenty something woman. "A good-paying job, somebody to be a good mother to my children, and a home of my own, of course," says a thirtysomething man. "And to take my kids to Disney World."

This class is the starting point for many people trying to move from welfare to work. The students are male and female, black and white, and range in age from early twenties to late forties. Asked about barriers to leaving welfare or getting work, they mention problems finding and paying for child care, the absence of public transportation, lack of education, lack of

April 1994/Illinois Issues/29

skills, a scarcity of full-time jobs, low wages for part-time work and, according to one woman who says she once griped about welfare recipients, a welfare system that "every time I take two steps forward knocks me back five steps."

One man complains that "four-something an hour is the only kind of job you'll get around here." A woman says, "I'm scared to get a part-time job because I want to go to school."

"If you get a part-time or temporary job," says Christenson, "it's getting a foot in the door."

They agree that Christenson's class has been helpful. "This class is good," says one student. "It teaches us what our skills are and how to improve our skills." Says another: "You don't feel alone. We all realize we're in the same boat."

Nellie Sampson used to be in that boat. Sampson, who lives in Chicago, grew up amid violence and sexual abuse. Her mother was the victim of domestic violence and left the family when her daughter was six. Sampson was sexually molested by her father from age three until she was 15. The two men who fathered her three daughters, ages five, 10 and 15, were abusive to Sampson. After working at a Montgomery Ward's store for 15 years, Sampson was laid off. She got pregnant with her third child, and went on public aid so she could stay home with her daughter during her early growing up years. When she tried to get a job four years later, nobody would hire her.

| A caseworker for Project Chance, the state's welfare-to-work office, referred Sampson to Chicago Commons' Employment Training Center (ETC), a program for long-term welfare recipients on the city's west side. Tests showed Sampson read at a seventh grade level and her math skills were at the sixth grade level. She went to ETC classes to boost her academic skills, while her youngest daughter came along to attend a Head Start program, also located at Chicago Commons. Sampson entered an incest survivors' support group at ETC, which, she says, "really helped me to lift the depression I was living with." After eight months she had raised her math and reading scores sufficiently to enter a computer training program in office technology. She graduated from the computer program after four months, but it took another five months for her to land a part-time job with a Head Start program, about a year ago. In May 1993 the job became full time and in July — after five years on public aid and 21 months in education, training and part-time work — she left the welfare rolls, though she continued to get support for her daughter's day care and her children's medical expenses. She is taking college classes at City Colleges of Chicago. |

|

In August, Nellie Sampson was among a parade of witnesses — present and former welfare recipients — who testified before the Working Group on Welfare Reform, Family Support and Independence, the task force preparing President Clinton's welfare plan. "There are a lot of people like me out there who want to better themselves but don't know where to go to get help," Sampson told the task force. "It is a very scary feeling getting off welfare. You really think: Am I going to make it?" Her fears of failure are common. Welfare recipients are often so beset with doubts about their abilities, so deflated by the stigma of public aid and so defeated by a welfare system that is uncaring and punitive that it is hard for them to even envision success.

"Nellie is a success story," Jody Raphael told the Clinton working group on welfare. "She is an example of how a job program does work."

Raphael runs the Chicago Commons ETC, which rests on the premise that clients need to build four kinds of skills to leave welfare behind: literacy, social and psychological competencies to help them overcome family and personal problems and leam to survive in the job market and, finally, job training skills. ETC has served nearly 400 clients since it opened in February 1991.

In her testimony, Raphael told the task force that 20 percent of the ETC clients had gotten jobs and left welfare, 25 percent dropped out of the program and the remaining 45 percent continued on their employment readiness plans. "Some participants can move ahead within six months," she said, "while others need between two

30/April 1994/Illinois Issues

and three years to complete the necessary steps. With all our experience it remains difficult to predict which participants will succeed in overcoming their problems and which will not. For many, the transition will require far more than two years."

| Raphael says participants in the ETC program spend at least six months in small group education where, with the help of teachers and a case manager, they learn the importance of basic but essential traits such as good attendance and punctuality. Other basic skills are a barrier for many welfare recipients as well, Raphael notes. Most job training programs and vocational training at community colleges expect at least an eighth grade reading level, and usually 10th grade, she says. But "nearly 40 percent of our participants come to ETC with reading levels at sixth grade or below, and an additional 30 percent range between sixth and ninth grade." Thus, nearly three out of four of the ETC clients need extensive academic help before they can pass their high school equivalency exam, a prerequisite for almost any entry-level job or training program. Typically, she says, clients reading at a seventh grade level need a year and a half to pass the GED exam. |

|

But academic shortcomings are not the only obstacle to work for many welfare recipients, nor even the most significant worry in their lives. According to Raphael, many clients have major — and tragic — social and family barriers to overcome. She cites these statistics:

• 54 percent of new participants during one 12-month period were living in domestic violence situations when they came to ETC.

• 13 percent had been victims of rape or incest.

• 14 percent had severe mental health problems, including depression and schizophrenia.

• 14 percent were abusing alcohol and using drugs, mostly marijuana and cocaine.

• 28 percent came from households with at least one child who had a severe physical or mental disability.

It is not uncommon, she says, for clients to have a combination of those problems. And, she adds, "ongoing domestic violence is one of the main causes for participant failure in the ETC program."

Success at ETC results from the broad-based nature of the program, focusing not just on clients' needs for training but on their employment aspirations, not only on their individual needs but on their family concerns and not only on short-term problems but on long-range goals as well. Each client prepares an employment plan — what job she would like to have (89 percent of clients are women) and what skills she needs to get it. Once clients achieve the literacy competencies they need, they are eligible for job training through ETC and City Colleges and can obtain internships with businesses that provide additional job survival skills, such as the ability to follow directions and complete tasks in a timely manner.

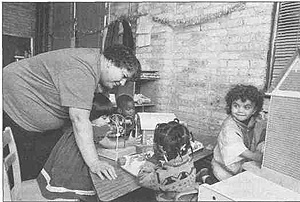

There is also a strong focus on family needs. There is an on-site health clinic, a family literacy center (with bilingual Dr. Seuss), a toy lending library and parenting and child development classes to help clients learn how to play with their children and to teach them. Two Head Start classes, funded by the city of Chicago, enable ETC to offer on-site child care, an especially important service to most clients. "The attitude about day care is a real barrier to work for many recipients," says Raphael. "They experience a tremendous amount of guilt" about leaving children in day care, she says.

|

Raphael and others who work with welfare recipients on a daily basis say case management is vital to successfully moving people from welfare to work. These case managers can kindly be referred to as 'mother hens' |

The mother hen for this whole system is the case manager, who helps the client through an 80-hour "life skills"program that tests the commitment to more intensive literacy, job training and personal problem solving. Case management was an idea that was much in vogue in the 1960s' version of welfare reform because it offered flexibility in dealing with the multitude of problems welfare recipients faced. But by the 1970s, the emphasis shifted to accountability and performance standards, and the concept of case management fell out of favor. Raphael and others who work with welfare recipients on a daily basis say case management is vital to successfully moving people from welfare to work. ETC has two full-time and two part-time case managers who customize services to client needs, assisting them in designing employment plans; helping them get access to domestic violence shelters, psychological therapy and alcohol and drug treatment; working with monthly support groups, like the incest survivors' group Nellie Sampson attended; helping plan for child care needs; and tracking clients for two years |

April 1994/Illinois Issues/31

after they get employment to assist in solving new problems and in keeping jobs.

The Chicago Commons ETC serves a neighborhood of 70,000 people; "50 percent of those 18 and over don't have a high school diploma," says Raphael. 'That's 30,000 people. The dropout rate at Orr [high school] is 60 percent and getting worse.

"We have a model that makes sense and you could plunk it down almost anywhere in Chicago," says Raphael.

Joyce Crawford-Bailey was at the Winfield-Moody Health Center for medical treatment in June 1986 when a sign on the wall caught her eye: "Interested in going to school? In getting job training? Contact Project Match." Crawford-Bailey, then a 25-year-old high school dropout, hadn't really thought much about either going to school or getting a job. She stayed at home in the Cabrini-Green housing development, one of Chicago's most notorious, collecting welfare benefits and tending her two-year-old daughter and school-age son. "I thought about it," she recalls, "and I decided that maybe I'd go in and see what it was all about."

It was about turning her life upside down. Project Match helped Crawford-Bailey get a part-time job, prodded her to get her high school equivalency and assisted her in getting into college. Within six months she was earning enough to disqualify her for a grant through Aid to Families with Dependent Children (although it only takes about $4,000 of annual income to make one ineligible for an AFDC subsidy). Now, eight years later, Crawford-Bailey works full time at Mt. Sinai Hospital as a case manager explaining to teenage moms why they should remain in school. In the next year or so she will finish her bachelor's degree in social work at Northeastern Illinois University. "Project Match," she says, "just changed everything."

"Leaving welfare is a process, not an event," says Toby Herr, director of Project Match. She says this to anyone who will listen, and she has had an impressive audience: Newsweek magazine, the Washington Post, the National Journal, a network newsmagazine, among others. Project Match is one of the most widely watched welfare-to-work programs in the nation, in part because of its sometimes controversial approach, in part because it deals with long-term, intergenera-tional welfare recipients, most of whom come from Cabrini-Green, the north side housing project known for its gang violence, drug dealing and abject poverty. Project Match, a private program set up originally by Northwestern University and funded as a demonstration project by the Illinois Department of Public Aid, operates out of the Winfield-Moody Health Center, within walking distance of Cabrini-Green. It has research affiliations with Northwestern and the Erikson Institute of Chicago, and has also received federal grants for a Head Start demonstration project. "We help people get on their feet," says Herr, "and we help them feel better about themselves."

"I told them I wanted to do something," Crawford-Bailey says of her first visit to Project Match, "computer programming or something." She was invited to a three-day orientation on the importance of education. "The people made you feel so comfortable," she recalls. She had dropped out of high school when she was 17 and pregnant with her first child, and the Project Match orientation helped her decide that "I needed to go back to school." She went through some Project Match training that helped her land a part-time job as a community outreach worker for a state-funded program to reduce infant mortality.

One of two Head Start classes at the Chicago Commons Employment Training Center on the city's west side. The on-site Head Start enables welfare recipients attending literacy classes at ETC to bring their children with them, a strong incentive for many welfare moms, according to the center's director. Photo by Jon Randolph |

As her income rose, so did her public housing rent, but her public aid grant dwindled, and finally disappeared after about six months. "I was able to manage," Crawford-Bailey says, "because the counselors at Project Match encouraged me not to give up. There were a lot of times I just wanted to give up." Counselors, as Project Match calls case managers, encouraged her to return to school and "they worked with my employer so I'd be able to go to school and work at the same time," Crawford-Bailey says. "They were an advocate for me." Eventually, she earned her high school diploma, something that had eluded her "after so many tries." She went to college, earned an associate's degree in social work at Harold Washington Community College and is now a senior at Northeastern Illinois. As her education credentials increased, so did her employment opportunities. She worked part time for a year and a half, first as a "health aide educator" and then as an outreach worker — recruiting young women in the community to join the infant mortality program. Eventually, she became a full-time case manager, counseling young mothers on the importance of prenatal care, good nutrition and |

Yet the reach of Project Match has extended beyond Crawford-Bailey's impressive rise from welfare. Her daughter, now a fifth grader, participates in Kids Match, which helped her get into the LaSalle Language Academy, a magnet school in Chicago, and also assisted in getting her a music scholarship from the Chicago Housing Authority. Crawford-Bailey's expe-

32/April 1994/Illinois Issues

rience has influenced the rest of her family as well. "I'm the first college student in my family," she says, "and it's a big family." When she first went to school, Crawford-Bailey recalls, her mother told her: " 'Child, you got to stay home and take care of those babies.' But now I have a sister who's going to go to college and another who's going to graduate from high school. With me doing something, it's changed the whole attitude of my family. I have plans for my son," a junior in high school. "He ain't stopping at high school.

"I have made a difference," Crawford-Bailey says. "There comes a time when you have to mature out of public aid. But if it weren't for Project Match, I'd have given up a long time ago."

Many do give up.

And so it was that Toby Herr, then a research associate at Northwestern University's Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research, founded Project Match in 1985 with the idea that most welfare-to-work programs focused too heavily on preparing a welfare recipient to get a job and too little on helping the recipient keep a job. As a consequence, many recipients — probably most of those in the long-term, hard-core category — wound up in low-paying jobs with few benefits and not much appreciation for the kinds of emotional and psychological adjustments they would need to make it in the world of work. They often found their way back to welfare.

"All the attention and all the help comes before the job," Herr told David Kennedy, author of a comprehensive report on Project Match for the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. "The job is the end of it. Programs do these very complicated assessments, they track people into education or training, or education and training, they do job development and placement, and teach resume writing and interviewing skills, they get people jobs: and that's it. A month later, or 90 days later you have no idea what's happened to people."

Herr wanted her program to know what's happened to people. If case management is considered a good idea or even an essential practice in other welfare-to-work programs, it is something of a religion at Project Match. Case managers don't so much serve clients as adopt them.

"From the very beginning, I always said, if a client comes in, drop everything," Herr says. "I wanted Project Match to be a place where people felt important and welcome. I wanted it to provide family-like support. We'll visit you in the hospital, we'll send you a card when your father dies, we'll come to your graduation, we'll come to your wedding. We'll be there for you. If you come in and get a job and everything's going fine and you're getting promoted, great: we'll call once a month and check in. If you just flunked the GED exam for the third time and you want to come in every afternoon for a week and grumble, that's fine too. If it takes you two years to get your first job and you need a lot of help keeping it, you can count on us. We are here for the duration."

One of the early findings of the Project Match program bore out Herr's suspicion that too little attention was being given clients after they got a job. Many clients, particularly those who had been through a host of "life skills" workshops or job search seminars, didn't want more training; they wanted jobs. But their experience in the work force quickly produced disconcerting revelations, both for clients and Project Match. Results from a sampling of 180 Project Match clients placed in jobs by February 1987 were discouraging: two in five lost their jobs within three months, over half within six months and at the end of a year 70 percent were unemployed. Some lost jobs because they didn't have the skills they needed, but many others simply found the adjustment to employment too difficult to make: they failed to arrive for work on time, didn't realize they should call in when they were sick, found it hard to take orders from a boss. Some were pressured by family or friends to leave jobs.

In some cases the jarring experience of losing a job taught clients that they needed to upgrade their skills. So they entered education or training programs. In other cases. Project Match caseworkers began to work on "re-employment" skills — how to show confidence at the job interview, what to do when a child's day care falls through, how to deal with a racist boss.

Meanwhile, Herr and her Project Match colleagues met many welfare recipients who weren't even ready for the education or training programs that would lead to work. Herr: "If you're a teenager with two kids, never worked before, involved with a guy who wants you to stay home and take care of him, just going to a GED class may be too much to handle, much less working your way off welfare. You really have to start where people are; you can't just walk into their lives and apply these broad prescriptions. You have to face that and you have to respect it, or you waste everybody's time and set everybody — especially the client — up for failure."

This insight led Herr to develop a new way of looking at the welfare-to-work journey. Many welfare recipients moved not so much in a straight line — from a GED class to a vocational program to a job — as up and down. They might start with a part-time job, then work on their GED, then get a full-time job, maybe go back to school, then a better paying job, perhaps get a promotion, and so on — like up and down a ladder. The top of the ladder is a stable job. At the bottom is anything that could get the client moving upward. "For some people, volunteering in a Head Start class three times a week is as big a step as getting promoted to crew chief is for somebody else," says Herr. "You have to challenge people, but you also have to be realistic and build up their confidence and abilities gradually. That's what the lower rungs are all about."

The lower rungs are the controversial part. The Illinois Department of Public Aid, a major contributor to Project

April 1994/Illinois Issues/33

Match, agreed with many precepts of the program: the emphasis on job retention, for example, and the long-term commitment to clients. But about 1990, the department began to lose patience with the notion that the lower rungs of Herr's ladder represented progress on the climb out of welfare. There is "accountability" in being able to count the number of clients who pass the GED exam or the number placed in jobs, the sort of yardsticks contained in "performance-based contracts," which Public Aid wanted to impose on Project Match. More difficult to measure is the increased sense of esteem or responsibility of someone who performs community volunteer work, no matter how important those traits might be to readying a person to trade welfare for work. Robert Wright, now the director of Public Aid, told David Kennedy for his 1992 Harvard study of Project Match: "You pay for things that are useful to you, what you want, and what we wanted was improvements in grade level, and GEDs, and on the job-placement side."

The concerns raised by Public Aid (and the prospect of losing state funding) prodded Herr to devise an accountability plan that left major tenets of her approach intact. This year, for the first time, Herr signed a performance-based contract with Public Aid that measures progress through conventional accountability techniques — the number of clients placed in jobs, for instance. But it also contains funds and leeway for Project Match to remain faithful to the principles and practices that Herr believes should govern successful welfare-to-work programs.

She is not so certain that welfare reformers understand those principles or practices. In February of this year, Herr co-authored a paper that states: "We are concerned that current proposals for welfare reform do not adequately reflect what has been learned in the welfare-to-work field over the past 25 years." Her paper noted that Project Match "is grounded in the understanding that for many welfare recipients leaving welfare is an uneven, back and forth process — not a single event. This process is characterized by false starts, setbacks and incremental gains." She then drew on the Project Match experience for lessons that welfare reformers should consider:

• Get a job, go to school — sometimes in that order. High school dropouts or graduates with low basic skills often get discouraged when transitional education programs, such as the GED, are their first step. "For many Project Match participants," Herr said, "a more successful route begins with employment. Only after experiencing low-paying jobs with few prospects for advancement do many really understand the link between school and work, and choose to make a commitment to school."

• Jobs don't grow on trees, waiting to be plucked by welfare recipients. Job development — that is, helping people locate and apply for jobs — is a faster avenue to employment than relying on clients to make independent job searches,

|

NIU study, Welfare Coalition cite flaws in Earnfare program

Two years ago this month, 83,000 people fell of welfare rolls in Illinois. Upon the urging of Gov. Jim Edgar, the General Assembly eliminated the state's General Assistance program, often called the "welfare of last resort," which mainly served single men with a monthly grant and medical benefits. Under a new welfare program called Transitional Assistance, those considered "unemployable" — people with mental physical disabilities, for instance, or those with severe substance abuse problems — could continue to collect a monthly check. Others were required to work for their welfare grant, first to pay off their food stamp allotment (a maximum of $112 monthly) and then to earn their monthly cash grant. The program was called Earnfare. Originally, Eamfare participants could work up to 61 hours a month and participate for a maximum of six months a year to earn a monthly grant of $154. As of January 1, the grant was raised to $231 and the maximum horus to 80. In January 1994, the Illinois Public Welfare Coalition released a study of Earnfare by researchers at Northern Illinois University that sharply criticized key aspects of the program, while calling for significant reforms. "This evaluation clearly shows that the original program of Earnfare is flawed," said Kelvy Brown, the coalition's policy director. "The long-term hardcore single unemployable adult cannot find and maintain a job just by working six months part-time. They need a wide variety of support services such as GED, medical, job search and skill development in order to move from welfare to work,"

The year-long study, conducted by NlU's Center for Governmental Studies, surveyed Earnfare recipients, employers who had hired them, community agencies that recruited and placed recipients in jobs and state Public Aid officials. Among the findings

a result of the study, the Public Welfare Coalition recommended that the amount of wages and number of hours be increased. It also urged that participants not be required to work off the food stamps they receive (other welfare recipients face no such requirement), and that medical benefits be provided (as they were under the former General Assistance program). Key among its recommendations was the suggestion that Public Aid pursue long-term jobs for participants. "More private sector employers should be identified, with an emphasis on retention of Earnfare participants who perform satisfactorily," the Coalition report said. It also said that participants should receive education and job-training to enhance their skills and make them more marketable in the private economy Donald Sevener |

34/April 1994/Illinois Issues

which has been the typical approach of many "workfare" programs, including Illinois' Project Chance, that evolved during the 1980s.

• People fall down, and need help getting back up. It is important to continue to assist clients even after they get a job because so many lose their first job. At Project Match, 70 percent of those who lost their first job were either working again within three months or attending school.

• Mother hens are needed. Case managers are crucial to helping welfare recipients cope with a multitude of problems that separate them from the world of work: from poor reading skills to domestic violence, from low self-esteem to gang warfare.

• Celebrate success. GED certificates dot the walls of Project Match the way Ph.D.s show off their diplomas. Every step up the ladder — new classes, graduations, volunteer positions, jobs obtained, jobs retained, promotions — is recorded in The Independence, the Project Match newsletter. This not only gives recognition to clients for their accomplishments but also established a powerful ethos: persevere.

• Stay the course. It's important to customize services to a client's needs and to make a commitment to the client for the long haul. Herr noted that one study of 259 Project Match participants found that the likelihood of employment rose 47 percent between their first and third years of participation in the program. Clients' average wages increased 23 percent between the first and third years of being in the program.

• Be patient and creative. "When Project Match examined the progress of individuals, rather than the total group, the outcomes were less optimistic," Herr reported. Half the Project Match participants made unsteady progress toward a job, meaning they may have held several jobs but none for as long as a year, or they made no progress at all over three years. This reinforces Herr's belief that options other than work or school — attending parent-infant classes, for instance, or volunteering in a school or community center — are needed to give some welfare recipients alternative routes to developing responsibility, commitment and competencies. She says these forms of community service — often promoted as a means of last resort for recipients who cannot get a job to "earn" their welfare check — are far more useful at the front end of the welfare-to-work process. Such activities can make up the lower rungs of the ladder and serve "as stepping stones and indicators of movement toward economic independence and family well-being." Community work, she adds, "makes the most sense early in the process rather than later as a dumping ground for those who are unable to get and keep jobs."

Herr urges a new "social contract" between government and welfare recipient, based not on sanctions imposed after an arbitrary time limit is reached but rather on incremental steps up the ladder to self-sufficiency.

"Unlike a time-limited approach where the stick (the loss of an AFDC grant) tends to fall at the end point, the 'incremental ladder' model nudges, pushes and pulls people toward stable employment from the outset and on a continuous basis," Herr concludes. "In a system where individual employ ability plans involve people in activities that are relevant to their personal goals and life situations, where they can progress in identifiable increments and where setbacks can result in revised plans, sanctions are likely to be imposed primarily on those who refuse to try to improve their lives."

|

All of this, naturally, takes money, though it is hard to pinpoint just how much. Public Aid is spending more than $65 million this fiscal year for education and training programs serving, on average, 30,000 welfare recipients in any given month. That amounts to roughly $2,200 per client to serve just over 10 percent of the estimated number of recipients who might qualify for and need such programs, according to the department.

Jody Raphael estimates it might cost anywhere from about $3,300 to upwards of $6,000 for clients who go through the Chicago Commons ETC, depending on their needs for education and training and on whether they go on to job-training programs. She says a Public Aid survey found that nearly 50,000 recipients read at below a sixth grade level and another 10,000 do not speak or write English, representing about 30 percent of the welfare caseload that could profit from ETC services. Toby Herr says that, on average, it costs between $1,300 and $1,400 a year to provide the education, training, counseling, and job development and followup services for a Project Match client. |

Herr urges a new "social contract" between government and welfare recipient, based on incremental steps up the ladder to self-sufficiency |

Chicago Commons ETC, depending on their needs for education and training and on whether they go on to job-training programs. She says a Public Aid survey found that nearly 50,000 recipients read at below a sixth grade level and another 10,000 do not speak or write English, representing about 30 percent of the welfare caseload that could profit from ETC services. Toby Herr says that, on average, it costs between $1,300 and $1,400 a year to provide the education, training, counseling, and job development and followup services for a Project Match client.

Joyce Crawford-Bailey says the money is well-spent: "It takes a lot to become independent from welfare. There were a lot of times when it was real hard and there was somebody to listen and help me from falling to pieces. If you have something like Project Match, you keep people from falling down and not being able to recover."

There is a way out of welfare. It takes education to teach basic skills like reading and why it's necessary to get to work on time. It takes counseling to overcome the effects of abuse, of violence, of drugs or alcohol, of broken families and broken lives. It takes training to teach marketable skills, like how to be a social worker, or an office worker or a dental assistant. It takes case managers, glorified "mother hens," to watch over people, to prod and push them, to nurture and comfort them, to help ease them through failure and help celebrate success.

And, of course, it takes patience.

Toby Herr knows the way. So do Jody Raphael and Nellie Sampson, Joyce Crawford-Bailey and Jane Minton and Karen Dare. What they don't know is whether welfare reformers understand the way out of welfare.

Donald Sevener is a Springfield journalist who has written extensively on issues of poverty.

April 1994/Illinois Issues/35

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |