|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

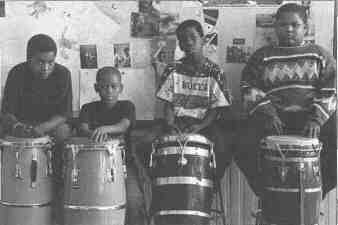

Ranked among Chicago's top 10 public grammar schools for best rate of improvement in math, reading and attendance in 1992, the Howland School of the Arts is situated in the heart of a west side ghetto called Lawndale. A sense of despair deadens life in a local economy dominated by drugs, welfare and the criminal justice system. But Howland proves that the community fabric has not totally unravelled. Inside this rundown, century-old brick building the hallways and classrooms hum with energy and optimism. As a participant in the Board of Education's "Options for Knowledge" program, Howland offers classes in music, drama, dance and visual arts to all students. It serves an area that is larger than the immediate neighborhood but not as big as a citywide "magnet" school. Students come from all over District 5 to take advantage of a curriculum based on the idea that learning through the arts encourages greater participation in one's education.

As the availability of government budget dollars decreases, public schools such as Howland are competing against others in the nonprofit sector — including human service agencies, universities, medical facilities, cultural institutions and community-based organizations — for support from private and corporate foundations. Foundations nationally give away about $9 billion a year. These "warehouses of wealth" maintain tax-exempt status by distributing 5 percent of endowments each year to nonprofits, thus helping citizens address needs, pursue hopes and press government to be more responsive. "The money is out there, all you have to do is take the time to write the grants," said Anita Broms, who took early retirement in 1993 after 20 years as Howland's principal. Claiming no organization ever turned her down, she said she also accepted donations of time and talent. She tended diligently to the strings attached — speaking to a foundation's board of directors, joining a community organization's board or increasing parental involvement in school activities: "I take your help anyway you want to give it." Philanthropic and government policy go hand in hand, with private monies augmenting federal plans. When the public spigot is turned down, they become the biggest trickle in town. Private philanthropies, with agendas of their own, force nonprofits to compete for money and to adapt when foundations shift priorities. Foundation dollars improve education and a host of other services in Lawndale — a place that most people make a point of avoiding. Located south of the Eisenhower Expressway (Interstate 290) between California and Cicero avenues in Chicago, Lawndale, basically the city's 24th Ward, includes 55,000 residents, 98 percent of whom are black. Half of the land is vacant and half the people on welfare. In 1966, when the civil rights movement waged an "end slums" campaign in Chicago, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sought to dramatize the plight of northern ghettos by residing in a drafty three-story tenement several blocks from Howland. A mile from Howland, looming above vacant lots and housetops, stands the industrial ghost town where 28/June 1994/Illinois Issues

A decade ago, when the Reagan administration was axing "wasteful" programs for the poor, White House staffers had the misconception that private philanthropy and voluntary service could pick up the slack, recalled Brian O'Connell, president of Independent Sector, a Washington-based coalition of 850 corporate, foundation and voluntary organizations that promotes giving, volunteering and not-for-profit initiatives nationwide. Not only did the government reduce its flow of monies to nonprofits, it imposed regulations that complicated the ability of agencies to draw resources from private funders — especially if their activities involved advocacy work which might, for example, criticize government's abdication of responsibilities to the poor. The day after a recent White House meeting, O'Connell said the Clinton administration shares many of its two predecessors' misunderstandings about the size of the giving sector. "As a society, we're not spending very much on programs and services that directly benefit low-income people," said Kirsten Gronbjerg, a Loyola University sociology professor and author of Understanding Nonprofit Funding. "Of total public welfare spending nationally, cash assistance for the poor amounts to only about three percent." She explained that public outcry on too much government spending usually targets social service programs, many of which are provided by nonprofit agencies. "These organizations depend heavily on public funding, with cutbacks hindering their capacity" to deliver services, she said.

In 1993 Chicago-area foundations and corporations gave $450,000 in planning grants to 14 partnerships — including 52 schools, 50 arts institutions and 25 community organizations. Recognizing that Chicago public school children have suffered from the virtual elimination of arts programming over the last decade, Marshall Field's convinced 12 foundations to finance the Chicago Arts Partnership in Education (CAPE). The program will fund an unspecified number of those 14 neighborhood

June 1994/Illinois Issues/29

If its five-year implementation plan is approved, Howland will be eligible to receive $60,000 annually over the next five years. The high stakes help explain why 45 people — including Howland teachers, parents and the janitor — endured subzero temperatures one Saturday last January to attend a downtown brainstorming session. In the competition for diminished foundation and other private charitable resources, places like Howland have an advantage. With the tight economy narrowing their own profit margins, most funders have reduced their giving. Chicago-area endowments, for example, gave $32 million in 1991 but $28.4 million in 1992. Many Chicago schools have a faculty member who has taken up grant writing because some pushiness and promotion "beats sitting there quietly and sinking," Polk Brothers Foundation executive director Nikki Stein said. Recalling a meeting of the Donors Forum, a consortium of Chicago area funders, where Howland kids went around the room giving everyone a hug, she added: "Anita Broms is a master at not letting her kids be forgotten." Stein observed, however: "People who aren't working with adorable children have a harder time selling their story." As Lawndale has degenerated through the years, its churches have become the key social organizations. Today, there are 60 with even the small storefronts housing an array of nonreligious programs such as meals for seniors, day care and a range of intervention services for neighborhood residents. Many foundations realize funding such community outreach isn't the same thing as funding religious activities, which traditionally are not funded. Congregations sponsor the outreach programs largely through religious networks and individual giving. They can get foundation support by stressing they are "the last hope, a remnant of glue holding the community together," said Claude Smith, former executive vice president of the Robert R. McCormick Tribune Foundation. Yet, such endeavors are often caught in another Catch 22: Unable to separate their activities from a congregation's operating budget, or lacking technical skills to write sophisticated grant proposals, many programs suffer from their inability to meet philanthropic standards for fiscal accountability. Together with Lawndale's schools and churches, 54 nonprofit human service agencies, funded through a combination of government contracts, individual giving and foundation support, provide services. Foundations help create a margin of success - or maybe just the avoidance of chaos. The criteria for foundation support may not be the most accurate available. 30/June 1994/Illinois Issues

That asset-based models work better than deficit-based models is an idea gaining currency. New approaches are definitely in order. "My conclusion is that what we can do is allow individuals more control over what sort of help they seek," said Joel Getzendanner, vice president of programs for the Joyce Foundation, which strives to fund "the new generation of ideas" such as proposals that are designed to help someone in five ways rather than having "five programs guess what that person needs." What Getzendanner sees — and supports — is people developing new institutional forms that look beyond the top-down scientific model of human organization. The seeds of social change are being sown in rural, urban, suburban and even corporate America, he said, due to what one prospective grantee calls "the epidemic of institutional collapse." Finding more effective strategies to improve conditions in ghettos is clearly something philanthropies need to do. In the last quarter century many foundations have poured support into community development corporations (CDCs). Due to their capacity to own and develop land, CDCs have emerged as inner-city institutions in recent years.

But philanthropic support can never be the key resource to defuse the social timebombs ticking near the heart of the nation's metropolitan regions. "Government has to take responsibility for having somehow failed in neighborhoods like this," said Father Michael Ivers, pastor of Lawndales's St. Agatha's Catholic Church, literally an oasis in a land of violence. This Afro-centric social justice congregation houses many community-based programs, including a scattered-site public housing resident group that went to federal court to force the Chicago Housing Authority and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to do their jobs — raze old buildings and build new ones. Last summer CBS-TV's Dan Rather went to St. Agatha to interview members of its gang intervention program. St. Agatha's programs try to maximize the charity within each person by inspiring them to do more. Ivers said nobody wants to be dependent on philanthropy, but foundation support remains critical and helps "contain the rage... Without foundations, conditions would be 10 times worse." Robert Heuer is a freelance writer in Chicago. June 1994/Illinois Issues/31

|