Poison pen pals

It is 6 a.m. in Springfield, and editorial cartoonist Mike Thompson is planning the day's attack on House Speaker Michael Madigan. In Chicago, Jack Higgins already has been up for two hours contemplating a pen and ink assault on Mayor Richard M. Daley. Downstate in Belleville, brothers Glenn and Gary McCoy soon will be discussing ways to blast U.S. Rep. Dan Rostenkowski (D-Chicago). While other journalists are consigned to a life of dreary objectivity and nitpicky details, an editorial cartoonist can sound off like the guy on the next bar stool. "Reporters can't write their opinions," says Jack Higgins, 39, Chicago Sun- Times editorial cartoonist. "We can draw the naked emperor." At a time when some feel the profession is suffering from wimpy editorial policies and a nationwide homogeneity (see sidebar), plenty of poison ink flows in Illinois. Higgins is one of at least 11 editorial cartoonists currently making naked emperors out of the state's political high and mighty. These guys — yes, they're all men — poke fun at pompous politicians with the grace of 270-pound defensive ends sacking quarterbacks. Today's Illinois cartoonists "do a terrific job," says Higgins, the 1989 Pulitzer Prize winner. "And the more voices the better." With its clown-studded cast of characters and constant political plot twists, Illinois is a cartoonist's paradise. Mike Thompson, who drew for newspapers in Wisconsin and Missouri before coming to Springfield's

State Journal-Register in 1990, says, "Illinois is in a league of its own for ridiculous politics. "This is probably the best state to be a political cartoonist in," says Thompson, a 29-year-old Minnesota native. "The congressional delegation is incredibly high-profile, the legislature is one joke after another, and you have constant battles — Chicago vs. downstate and Chicago vs. the suburbs." Higgins generally addresses state and local issues in three of his four weekly cartoons for the Sun-Times. The son of a Chicago cop, Higgins loves working in the Windy City. "Anywhere you have polarization between personalities, regions and political philosophies is rich [territory] for politi- cal cartoons. [Polarization] creates tension, and something has to give." Chester Commodore, 80, cartoonist with the Chicago Daily Defender since 1948, has enjoyed Chicago not only for its abundant topics, but also for his access to black leaders. "Dick Gregory, Jesse Jackson, Bobby Seale, they all used to come into the office and talk with me," says Commodore, the state's only African-American editorial cartoonist and one of a handful nationwide. "When Harold Washington was in Congress, I got a lot of letters from him," says the semi-retired Commodore. "He always liked what I published." A self-described "Republicrat," loyal to neither political party. Commodore also received "complimentary letters" from Richard Nixon and J. Edgar Hoover. The Chicago Tribune's Dick Locher, 65, says he addresses local topics about once a week even though his work is nationally syndicated. "Chicago is national," he explains. "When we 12/August 1994/Illinois Issues

This illustration shows Mike Thomp- son's famous "price tag" in the hair of Gov. Jim Edgar. He tells in this article why he always uses the price tag.

August 1994/Illinois Issues/13 do a Richard Daley cartoon, it's not just local," says the 1983 Pulitzer Prize winner. "In California, Richie is not big, but Richie is big in Washington, D.C." "Mayor Daley is always fun," says Roger Schillerstrom, 38, of Grain's Chicago Business. "Higgins draws him as a brooding, mean-spirited creature. I kind of draw him as a mischievous little kid — there's always some point in editorial board meetings where he throws a little tantrum." Local targets, of course, are not confined to Chicago. Glenn McCoy of the Belleville News-Democrat calls his community the state's "best place outside of Cook County" to draw political cartoons. "East St. Louis is a godsend for a cartoonist," says the 28-year-old Belleville native. "With its corruption and dirty deals and crime, it has every political issue and social issue a cartoonist can take aim at. East St. Louis is a microcosm of all the things that have gone wrong with this country.

"When Carl Officer was mayor of East St. Louis and running a very corrupt organization, I did three or four cartoons on him a week for a time," says McCoy. After he depicted the mayor as "fat with a cigar," a number of African-American churches circulated petitions calling for McCoy's firing. But, says McCoy, "When Officer was voted out of office, [members of] the East St. Louis Police Department called and wanted to take me out to dinner because they felt my cartoons played a role in getting him voted out." Glenn McCoy's 31-year-old brother, Gary, draws for the Suburban Journals of Greater St. Louis, a chain of weekly and twice-weekly newspapers on both sides of the Mississippi. "I think the community likes seeing the local stuff," says Gary McCoy. "It's a big thing to them just to have an editorial cartoonist covering local issues." Illinois' political cartoonists are part of an American tradition as old as the nation itself. Ben Franklin and Paul Revere produced and distributed political engravings to help stir illiterate, disinterested colonists into supporting the revolution. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln called Harper's Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast "the Union's best recruiting sergeant" for his powerful anti-Confederacy cartoons. In the 1870s, Nast almost single-handedly toppled New York City's corrupt Tammany Hall political machine. His relentless depictions of political fixer William "Boss" Tweed and his cronies as scheming crooks drove Tweed to rant, "Stop them damn pictures! My constituents can't read. But, damn it, they can see pictures!" ¦ Many of this century's best editorial cartoonists have drawn their "damn pictures" in Illinois. Since the 1930s, Chicago cartoonists have received numerous awards for editorial cartooning. Two Pulitzer Prizes and three other top awards went to Bill Mauldin, Chicago Sun-Times cartoonist from 1962 through the late 1980s. Mauldin, who gained fame as a World War II infantryman with his famous cartoons of American G.I.s "Willie and Joe," became perhaps the most influential editorial cartoonist of the 1960s. He set the pace on issues other commentators were only beginning to touch, such as civil rights, the environment and the Chicago political machine. Before World War II, the Chicago Tribune's John McCutcheon, Joseph Parish and Carey Orr led cartooning's "Bucolic School," drawing upbeat, patriotic cartoons from a distinctly midwestern perspective. Their contemporaries — Vaughn Shoemaker (Chicago Daily News), Jacob Burck (Chicago Times, Chicago Sun-Times) and Art Young (Chicago Tribune, Chicago Daily News, Chicago Inter-Ocean) — pioneered a drawing style heavy on grease pencil and crayon. The technique was adopted by Mauldin and practically every other American cartoonist of the 1940s and '50s. And the John Fischetti Award, established in 1982 in honor of the late Chicago Daily News cartoonist of the 1960s and '70s, has become nearly as prestigious as the Pulitzer Prize within the profession. But the most influential Illinois cartoonist worked in the state for only four years. Herbert L. Block — better known simply as Herblock — drew briefly for the Evanston News- Index and spent 1929-32 with the Chicago Daily News before moving on to syndication and the Washington Post. A three- time Pulitzer Prize winner (1942, 1954 and 1979), Herblock drove Richard Nixon to tell campaign aides in 1960, "We have to erase the 'Herblock image.'" The cartoonist had angered Nixon by repeatedly drawing him as a sewer-dwelling scoundrel with a sinister five-o'clock shadow. In a 1977 survey of editorial cartoonists, Herblock's peers overwhelmingly named him the "greatest" working editorial cartoonist and a major artistic influence. "I remember sending a Herblock cartoon around to my colleagues before a vote," says U.S. Sen. Paul Simon (D-Illinois), who believed the cartoon might sway senators' opinions. Simon calls Herblock the "most influential" cartoonist he knows. Pat Quinn, state treasurer and Democratic candidate for secretary of state, says, "Herblock and (former Washington Star cartoonist Pat) Oliphant helped form my political views when I was a student at Georgetown. Herblock would take the side of the underdog. He was a champion of people who didn't have lobbyists and friends in high places. And he was good at bursting the pomposity of many of the people in elected office." Do today's Illinois practitioners measure up to the state's rich cartooning legacy? "I think Higgins is particularly good," says Herblock, who, at 84, has no plans to retire, "and Dick Locher, [Jeff] MacNelly — they're all good. Higgins does an awful lot of local stuff and not enough people do that these days. More local stuff is one reason I'm so interested in Higgins. He's kind of in the Thomas Nast tradition." 14/August 1994/Illinois Issues Sen. Simon says, "I go through both Chicago papers every day and I look at the cartoons. I know more people will look at cartoons than read editorials." Simon says his "impression is that [cartoons] do have an impact on public policy." Simon figures he can't avoid being caricatured. "With distortion of features, I'm a natural for cartoonists," he says. "I can't say one cartoon made me mad, but there have been cartoons that distort the issues." Although Pat Quinn has been the target of cartoonists, he seems to view them as allies. During Quinn's petition drive to cut the size of the Illinois House 14 years ago, he says, "A lot of cartoonists got on the fat cat legislators. That definitely had an impact in moving citizens to help our cause. Citizens would call and say, 'I just saw this cartoon, how can I help?' "Insiders use their positions to get unfair advantages," says Quinn. "That's when editorial cartoonists rise to the occasion and catch 'em in the act of being unfair." Some politicians think it's the cartoonists who are unfair. The late Mayor Harold Washington once sent Jack Higgins a message to "Drop dead." More recently, says Higgins, "on six or seven occasions, people who work in City Hall would tell me, 'Richie [Daley] went through the roof today about your cartoon.' I guess he's very sensitive to criticism." At a Chicago Tribune editorial board meeting, Dick Locher recalls, "Richie Daley said, 'Locher, come over and sit by me, and you'll see I'm not as fat as you draw me.'" In the midst of 1960s' race riots, Chester Commodore once drew Cook County Sheriff Joe Woods "in a Klan outfit ... shooting a pistol in the street" and starting a riot. "[Woods] came in with two bodyguards — the biggest guys I've ever seen in my life — and he wanted to know who Commodore was," recalls the cartoonist. "He went around the newsroom and all the reporters said they were Commodore. When he got to me — I was the last one he came to — I put out my hand and said, 'I'm the real Commodore,' and he slapped my hand away. "He said, 'that [cartoon] was yellow journalism,'" says Commodore. "I told him, 'no, it was black journalism.' He would not shake hands with me."

In Mike Thompson's frequent caricatures of Gov. Jim Edgar, he always draws a price tag on the governor's head, as a jab at the perfectly groomed Edgar's perceived preoccupation with keeping every hair in place. "I heard a story — I'm not sure it's true — that when Edgar won the election he sat up all night in a recliner to not muss up his hair," says Thompson. "Every time I see him he asks me about [the price tag] and I deliberately never tell him. I was just going to draw it for a while, but I found out he was a little annoyed by it, so now I'm going to do it forever."

Edgar's predecessor, Gov. James Thompson, was a fan of political cartoonists, and particularly Bill Campbell, who hilariously satirized state politics for the Quad-City Times and other Illinois newspapers in the late 1970s. "Although sometimes his August 1994/Illinois Issues/15 pen is soothing," Thompson wrote of Campbell in 1980, "I have also felt its sharp jab and literally 'got the point.'" When a truck accident paralyzed Campbell and cut short his career in 1979, Thompson visited the cartoonist in the hospital. "Gov. Thompson was one of Bill's real fans — and also one of his chief targets," says Michael Lawrence, Edgar's press spokesman and Campbell's former syndication partner. "My hunch is that Gov. Thompson paid a lot of attention to what Bill did — and took the criticism to heart, because I know he respected Bill quite a bit." Democratic gubernatorial candidate Dawn dark Netsch still reacts with "surprise" when she sees herself caricatured. "I was a member of the Senate for 18 years and I was never cartooned in those days." For now, Netsch seems to enjoy her new status as a target. "I remember a couple f of cartoons] that were marvelous during the primary race. One showed my opponents [Richard Phelan and Roland Burris] with their clothes off. That was, I thought, pretty funny." Private citizens' reactions to cartoons vary. Glenn McCoy says, "I get the most angry responses when I slam [President] Clinton. I get the most favorable responses when I do something local." Locher says readers send him 20 to 30 letters a day — mostly negative. But his Tribune colleague Jeff MacNelly, a three- time Pulitzer Prize-winner, offers a different view. "I got the feeling you couldn't shock Chicago readers," he says. "You could say anything about the mayor and readers would say, 'what else is new?'" But MacNelly, 46, pushed the wrong button for some readers when he depicted a Roman Catholic priest as a child molester. "Chicago went completely ballistic, like a neutron bomb," says MacNelly, adding that Cardinal Joseph Bemardin demanded an apology from the newspaper. MacNelly, who draws for the Tribune from his home in rural Virginia, applauds his editors for backing him up in the face of such controversy. "If I draw a controversial cartoon," he says, "they're more courageous about running it than I am. [Editorial Page editor] Don Wycliffe treats me like a columnist."

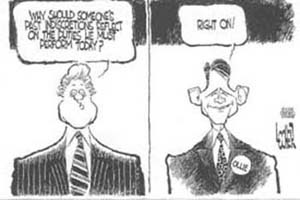

Most cartoonists officially maintain political neutrality. "I'm an equal opportunity critic," explains Mike Thompson. "No party or politician has a monopoly on gaffes." Yet most of these artists develop favorite targets and pet issues. Higgins' favorite topics have included the troubles within the Chicago public schools and the Chicago Housing Authority. Dan Ackley, 26, cartoonist for Bloomington's Pantagraph since last April, sees Dawn dark Netsch as his prime target: "I can't stand her tax and spend politics," he explains. Roger Schillerstrom devotes many Grain's cartoons to Mayor Daley and "the legislative stalemate between Pate Philip and Mike Madigan." Locher and others have taken aim at proposals to expand legalized gambling. "I wish 'Daley Jr.' would get off that riverboat deal," says Art Henrikson, 73, of the Daily Herald in Arlington Heights. "I think it's a no-win deal. Atlantic City is worse off than it was before gambling came in there." Henrikson recently portrayed gambling promoters "reading bedtime stories to wide- eyed communities, where everyone lives happily ever after." The state's cartoonists all expect this fall's governor's race to be close and they are split on which candidate they support philosophically. But nearly all agree on one thing: From a caricature standpoint, Netsch is much better than Edgar. "Edgar's too good looking," says Gary McCoy. "Edgar is so bland and tasteless," says Glenn McCoy. "He doesn't look like a politician should look," says Henrikson. "You have to emphasize his square face and his chin, which is a little pointy," says Schillerstrom. Netsch, on the other hand, "is just an incredible venture for cartoonists," says Locher. "Netsch has a great face for caricature," says Glenn McCoy, "and each time you draw her you can push it a little more." What do these guys have to say about a profession which places a candidate's facial features above her political views? "We're lucky," says Henrikson, speaking, as cartoonists often do, in metaphor. "We get to stand on the sidelines and I Locher adds, "An editor said to me: ' 'You guys watch the battle from the top of the hill and then go down and shoot the wounded.' But I think editorial cartoonists are like the blind javelin thrower at the Olympics. We don't win a lot of awards, but we keep the crowd alert." Mike Cramer draws cartoons on state and local politics for Illinois Issues, Illinois Times, Capitol Fax and the Illinois State Bar Association's Bar News. He moved recently from Springfield to Chicago, where he is a part-time lawyer and continues cartooning with an eye on the Statehouse. Illustration by Glenn McCoy, Belleville News-Democrat 16/August 1994/Illinois Issues

In the 1920s and "30s, when Herbert "Herblock" Block's cartoons graced the Chicago Daily News' editorial pages, cartoonist Vaughn Shoemaker's work appeared on the paper's front page. Herblock, 84, explains that in those days each of Chicago's numerous newspapers had a blatant political slant and made no pretense of political objectivity. "They used to run front-page editorial cartoons in the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Daily News," he says. "Sometimes papers ran front-page editorials, too." In those pre-TV days, cartoons got royal treatment. "Editorial cartoons got more space then, too," says Herblock, "as did comic strips. Newspapers played up cartoons." Today, some cartoonists complain that newspapers have abandoned good editorial cartoons and strong opinions. "What the newspapers are doing is dumbing down," says Paul Conrad, 70, a three-time Pulitzer Prize winner from the Los Angeles Times. "The bottom line is money. They don't want any problems with readers." And many cartoonists today contribute to the problem by shunning state and local topics in favor of subjects less controversial and more glamorous — and more likely to be reprinted in Newsweek. The result, say some, is a nationwide abundance of bland, opinionless cartoons. Herblock, of the Washington Post, says, "There are a lot of good cartoonists around, but also a lot who draw something that's funny but doesn't say too much." At June's Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) convention in New Orleans, Conrad warned a crowd of his peers and heirs: "Unless cartoonists start to say something, they have a very dim future.... What burns me up is that cartoonists are dumbing down [with newspapers] and going along with it." In a roundtable discussion at the gathering of nearly 200 AAEC cartoonists, member after member questioned the profession's direction. "Cartoonists are increasingly seen as liabilities," said Steve Greenberg of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. "Newspapers .... can't afford to offend readers and lose them." "The state of the art is really getting pathetic," lamented syndicated cartoonist Wiley Miller. "Editors don't want you to have an opinion — that's the last damned thing they want. An editor's worst fear is readers calling to complain."

Editorial freedom varies among Illinois cartoonists. "This has been a common gripe since 1960, when I joined AAEC," says the Daily Herald's Art Henrikson, 73. But, he adds, "I've never been limited at all in what I wanted to say in my cartoons." "I get total freedom," says the Chicago Tribune's Jeff MacNel- ly, who has the clout of three Pulitzer Prizes and the advantage of agreeing with his editors on many issues. "[My editors] stand behind me when I get in trouble. Any editor worth his salt will do that." Belleville News-Democrat cartoonist Glenn McCoy agrees — partially. "I think my editors like to evoke anger or some response from readers. But that's only up to a point. When people start dropping subscriptions, [editors] start to sweat." Gary McCoy, on the other hand, has had numerous cartoons killed by his editors at the Suburban Journals of Greater St. Louis. "If all I can draw is 'Don't drink and drive' cartoons on New Year's Eve, that's not enough," says McCoy. "I'd like to do harder hitting stuff." Similarly, Roger Schillerstrom is resigned to toeing the Grain's Chicago Business company line. "It's not as if [my cartoon] is 'the Schillerstrom opinion,'" he says. "It's the Schillerstrom opinion that matches the editorial position of the paper." All of these guys would agree with Tony Auth of the Philadelphia Inquirer. "American newspapers are making a big mistake when they don't use lots of political cartoons and spread them around on the op-ed page," Auth told his AAEC audience. "Readers like cartoons ... and they like strong, acerbic cartoons." Mike Cramer August 1994/Illinois Issues/17

|

|||||||||||||||