Business has been brisk at Romeo Alarm Systems, a Springfield firm that specializes in home security. "The fact is, people are scared," says Pat Rotherham, Romeo's president, "and home security seems to be the answer. Our business has soared in the last 10 years." Romeo is planning a new building that will quadruple the space the company now has, and Rotherham predicts that within three years the firm will need to more than double the size of its new facilities. "It's a shame we have to live with that kind of fear." By all accounts, the fear of crime is palpable, and growing. People are scared. Gauges of mounting public anxiety are plentiful: An Associated Press poll in May found that 60 percent of Americans fear becoming a victim of crime. A Time Magazine poll in January revealed that one in five respondents identified crime as the main problem facing America nearly double the number who said unemployment or the economy was the nation's principal concern and five times the number who said crime was the number one problem a year earlier. A New York Times/CBS poll found the same trend two years ago, concern about crime and violence barely registered on the scale, but in April 1994 one in four respondents said crime was their chief worry, more so than economic issues or health care. A 1994 survey by the Institute for Public Affairs at Sangamon State University found that the number of people who said they had been victims of crime just under a quarter of respondents was virtually unchanged from a similar poll three years ago. But the number who said crime

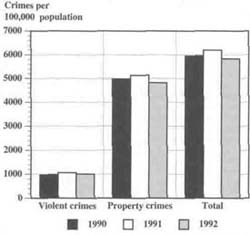

Trend in serious crimes in Illinois, 1990-1992

is one of Springfield's most serious problems jumped 30 percent in the most recent survey. Since 1987, the number of people obtaining firearm permits from the Illinois State Police has risen 13 percent. Among women, the increase is 42 percent. As Romeo's experience shows, the electronic security business has mushroomed. Propelled by significant increases in home security systems particularly, sales of alarm systems have risen 20 percent a year since 1985, according to an industry marketing study. Statistics compiled by a trade association indicate that a third of households with incomes over $100,000 are protected by a home security system. In 1988, the residential security business alone was a $5.4 billion market. Small wonder then that politicians have moved swiftly to exploit voter fears. In June, Gov. Jim Edgar threw the first punches in his re-election campaign against gubernatorial opponent Dawn dark Netsch with television commercials attacking the Democratic candidate's record on mandatory sentencing legislation when she was a state senator and her opposition to capital punishment. "Public opinion polls have documented that crime ranks among the chief concerns of the people of Illinois," noted an Edgar background paper, entitled "A clear choice: The crime issue." "Throughout his career in public office, Edgar has taken a hard line on crime. Netsch's voting pattern during nearly two decades in the General Assembly indicates she is out of touch with the mainstream of Illinoisans on the crime issue." Netsch has long been skeptical of tougher sentencing laws and has said that she would emphasize measures like community policing and alternatives to prison, such as home detention, boot camps and reduced sentences for those who participate in drug rehabilitation programs and educational classes. 18/August 1994/lllinois Issues

Meanwhile, candidates for attorney general sound more like they are running for county sheriff as they try to outduel one another with anticrime rhetoric. "I am going to expand the power of the attorney general's office to fight crime in Illinois," Republican candidate Jim Ryan, the DuPage County state's attorney, has vowed. His Democratic opponent says, "As Illinois attorney general, Al Hofeld will fight to furnish Illinois with a justice system that keeps violent repeat offenders behind bars, domestic violence laws enhanced and enforced, and stricter gun control measures implemented." Driven by the high pitch of public emotion, the focus of the political response has been, as it typically is: Get tough on crime. The anticrime bill now before Congress calls for spending billions of dollars for additional police and new prisons. And lawmakers from Washington, D.C., to Washington state, and everywhere in between, have jumped aboard the bandwagon of tougher sentences for convicted felons. Yet, amid all this trepidation there is strong evidence to suggest that public fears about crime may be somewhat overblown. Amid the enthusiasm for the lock-'em- up approach to criminal justice, there is scant evidence that the get-tough policies advocated by politicians do much good. Rather, proof is abundant that government by slogan Three Strikes and You're Out, Truth in Sentencing will cost taxpayers lots of money while doing little to reduce crime. Ironically, the public fear of crime seems to be mounting just when serious crimes have been leveling off. According to figures compiled by the Illinois State Police, both the total number of serious offenses and the crime rate (the number of crimes per 100,000 population) dropped by nearly six percent in 1992 from the previous year. In Chicago, which accounts for about 45 percent of all serious crimes reported to police in Illinois, the overall rate of "index" crimes murder, rape, aggravated assault, robbery, burglary, theft, motor vehicle theft and arson fell 7.5 percent in 1992, the most recent year for which comprehensive statistics are available. "The FBI crime reports show the rate of most violent crime is flat or declining not by much, but certainly there is no surge in the crime rate," notes Donald Dripps, a professor of law at the University of Illinois. "It is not the case that we are experiencing dramatically more crime. But that doesn't mean that people are irrational to be afraid of it." Indeed, regional breakdown of crime statistics and a longer time frame reveal somewhat different trends. In April, the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority completed a county-by-county analysis of crime. According to its study, between 1988 and 1992 the rate of violent offenses rose 24 percent in Cook County, 17 percent in both urban counties and rural areas and one percent in the collar counties. Statewide, the violent crime rate rose 15 percent during that period. Still, though people are most fearful of violent crime (and murders and rapes have registered slight gains even as the overall crime rate declined), the odds that the average citizen will be victimized by violent crime are relatively low. Most violent crime occurs between people who know one another. Moreover, for those unlucky people who are victims of crime, most are far more likely to be victimized by a property crime burglary, theft than a violent one. For every violent crime committed, five property crimes are committed. And property crimes have shown steady declines or, at worst, only modest growth for several years. Between 1988 and 1992, serious property crimes rose slightly in downstate urban and rural counties while actually declining by two percent in Cook County and eight percent in the collar counties. Statewide, the property crime rate rose one percent. August 1994/Illinois Issues/19 "A lot of areas have seen decreases," says Jeff Travis, a research analyst for the Criminal Justice Information Authority. In Sangamon County, for instance, while the rate of violent crime rose 49 percent between 1988 and 1992, there were actually fewer property crimes reported in 1992 than a decade earlier. Same in Peoria County violent crime rate up 41 percent, property crime rate down. Same trend in Rock Island County and Madison County. Same in McHenry, Kane, Lake and DuPage counties. In Champaign and Will counties the rate of violent crime and property crime declined during the 1980s. Notwithstanding recent crime trends, Travis has a more sobering observation. "We've settled on a higher constant of crime," he says. What he means is that crime trends are somewhat cyclical a period of steady growth, followed by a period of leveling off, or even some declines, as we're experiencing now. But each new period of growth starts from a new, higher level of crime. Though it may be of some comfort to the people of Cook County to know the rate of violent crime dropped about 10 percent in 1992, compared with 1991, they probably find less solace in the fact that the rate more than doubled between 1982 and 1992. On the other hand, police seem to be keeping up. While the rate of violent crime rose 17 percent in urban counties between 1988 and 1992, the arrest rate for violent criminals jumped 26 percent. In rural counties the arrest rate outpaced the increase in violent crime 22 percent to 17 percent. In the collar counties, the arrest rate for violent offenses was unchanged during the period, but the rate of violent crime rose just one percent. Even in Cook County, the arrest rate nearly kept pace arrests were up 18 percent compared to a rise in the violent crime rate of 24 percent. Statewide, arrests rose 20 percent, violent crime 15 percent. The trend is actually better for property crimes. In all regions and statewide, the arrest rate outdistanced increases in property crimes. So on balance, though violent crime has increased during the 1980s, other trends suggest that the public's temperature over crime is rising at a time when people might reasonably feel a bit safer. What are people afraid of? "A lot of things build into the fear," says Travis. Few people, he notes, get the long view, "the statistics of a 10- to 12-year pat- tern." Instead, he says, "understanding of crime is based on bits and pieces what you read in the newspaper, something that happened to a neighbor and that skews your understanding. "These are serious issues that scare people. You see more and more about youthful offenders and that puts a fair amount of fear into the public," says Travis. "There is story after story of 12-year-olds with firearms and suddenly you see there is a whole new population of people committing violent crimes. You see stories about 'three strikes and you're out' and that starts talk about how quickly people get out of prison. Without seeing the whole picture, it's easy to have your perceptions influenced by those things and you begin to say: 'Holy cow! This is really a dangerous place.'" It is the response to that emotion, rather than a response to crime, that most frequently motivates the political message. For example, a central theme of Edgar's commercials against Netsch was her opposition to mandatory sentencing provisions in a variety of "tough-on-crime" measures considered by the General Assembly during her 18 years in the Senate. Supporting information supplied by the Edgar campaign for one ad said Netsch was among only seven senators to vote against legislation in 1977 to automatically jail a person accused of a "forcible felony" while out on bail. A member of the House at the time, Edgar supported the bill. Also, the back-

ground paper asserted that Netsch voted five times against bills to impose mandatory prison terms (including for youths as young as 15) for persons who use a gun while committing a crime. Finally, the commercial asserted that Netsch opposed mandatory life sentences for felons convicted of a third serious felony the so-called "three strikes" provision originally added to the state criminal code in 1977 as part of the Class X crime package. According to debate recorded in Senate Journals, Netsch called the three strikes provision "a phony issue," "newspaper grandstanding" and "a terrible, terrible idea" that "is not going to have the impact it is represented to have." Indeed, the principal impact of get-tough measures has been on the state's treasury. In 1977 when the state began its campaign to toughen penalties and build new prisons, there were about 10,000 inmates in Illinois penitentiaries. Seventeen years and fifteen new prisons later, there are now more than 35,000 inmates. The unprecedented building program, which has not ended, cost $459 million for construction alone, not counting financing or operating costs. On average, it costs about $16,000 to feed, clothe and house each inmate for a year. In 1977, the Department of Corrections operating budget was $97 million. Its appropriation for fiscal year 1995 exceeds $700 million. The cost might well have been worth it if the crime rate had been affected in any significant way. It hasn't. The number of serious violent crimes rose 82 percent between 1983 and 1992. Even as Illinois more than tripled the number of people incarcerated in prison, the rate of violent crime rose steadily throughout the eighties before beginning to level off in the early 1990s. "None of that stuff helps particularly," says Dripps of the get-tough approach to fighting crime. "We imprison more people and incarcerate them longer than anybody in the world. There surely is some benefit to that, but it obviously hasn't solved the problem yet, and it is horrendously expensive." 20/August 1994/Illinois Issues

Yet, he notes, "there is no slaking of appetite for more of the same. Tough on crime appeals at a moral level; people have a taste for punishment because it validates their own lives. It makes people feel better about living a law-abiding life." So punishment is what the politicians offer. Andrew Leipold, a colleague of Dripps at the U of I law school, says there are "some good, thoughtful, intelligent politicians who have thought these things through." And there are others, he adds, who "sign on to anything that sounds like it's tough on crime because that is what is popular." One idea that seems to be gaining popularity is "truth in sentencing," which has the appeal of a snappy title with the added advantage of tangible, if rather extravagant, tough-on-crime results. Simply put, the proposal would force convicted felons to serve 85 percent of their sentence before becoming eligible for parole. Currently, because of a variety of "good time" credits, inmates of state prisons serve less than half their sentences. Eleven states limit good time credits and require that a felon serve at least 80 percent of his or her sentence, including four states that enacted truth-in-sentencing legislation within the past year. Though none of several truth-in-sentencing bills before the General Assembly passed during its spring session, the impetus to do so is strong. The federal crime bill includes provisions for construction of new regional prisons, but would require states to implement truth-in-sentencing legislation to use them. That could be a bad bargain. Last month the Criminal Justice Information Authority released a report on truth in sentencing that provides a revealing case study of the high cost and low yield of the lock 'em up approach. The authority's study notes that proponents of truth in sentencing contend it would reduce the crime rate by keeping felons off the streets for a longer time, curtail recidivism among ex-offenders who would be beyond the "crime-prone" years when released from prison, strengthen the integrity of the criminal justice system and curb costs by offsetting increased incarceration expense with reduced costs associated with prosecuting criminals and the crime victims. Opponents argue that elimination of good-time credits for education and vocational programs would hamper the ability of prison officials to promote good conduct and would increase the risk of violence in prison. They also assert that truth in sentencing would further burden already dangerously overcrowded prisons, and that judges would simply adjust sentences so the net gain in time served would be negligible. The authority's study found that truth in sentencing would add two years and nine months to the time served in prison by the average offender. It would also add 45,000 inmates to the Illinois prison system at a cost of $5.8 billion over the next decade. The study confirms what many people suspect: Most inmates do not serve anywhere close to the number of years they are sentenced to prison. Because good behavior is rewarded with a reduced sentence, the average inmate serves only about a third of the prison sentence imposed by a judge, ranging from a year and a half of time served by a person convicted of a property crime to about three years and three months for someone convicted of a sex offense. A felon convicted of a crime against another person aggravated battery, for example, or armed robbery might be sentenced to slightly more than eight years and serve about two years and eight months in prison. Under truth in sentencing, the average offender would serve four years, nine months, compared to just under two years now. But the impact on some inmates would be dramatic. Convicted murderers, who now serve about 10 years, would have to serve more than 25 years in prison. Class X felons convicted, for instance, of selling more than 15 grams of cocaine, or of home invasion would spend an additional five years, four months behind bars under truth in sentencing. So would the crime rate go down? Not necessarily. When social scientists and criminal justice experts talk about the relationship between incarceration and crime, they use terms such as "incapacitation effect" and "recidivism" and talk about the "crime-prone age bracket." A murderer who spends 25 years in prison instead of 10 would be "incapacitated" for an additional 15 years. However, as the authority's report notes, murderers make up only 1.6 August 1994/Illinois Issues/21 percent of the people sentenced to prison, and "since many homicides are not premeditated but are rather crimes of passion, the deterrent effect of longer sentences may be minimal." The effect on Class X felons would be more significant. On average, those convicted of serious violent crimes such as attempted murder, aggravated criminal sexual assault and armed robbery would be incapacitated by longer prison terms ranging from 5.6 to 6.5 years. Yet, the effect on those convicted of lesser felonies most drug charges, burglary, theft, battery would be small, raising the average time served by less than three years. Nearly three in four felons sent to prison are sentenced for such crimes, leading the authority's analysis to conclude that the incapacitative and deterrent effects of truth in sentencing would be negligible for the vast majority of criminals. More significant might be the effect of truth in sentencing on the age of ex-offenders and on recidivism, that is, their propensity to commit new crimes and return to prison. Older people commit fewer crimes than younger ones and to the extent that truth in sentencing increases the age at which felons are released from prison, it could influence the likelihood they would not go back. There is nearly a 60 percent chance that someone released from prison at age 20 will commit a new crime and return to prison; at age 56, the likelihood of recidivism is only about 15 percent. Overall, the proposal would raise the average age of persons released from prison from 30.6 to 33.4. The recidivism rate of 30-year-olds is 47.5 percent, while 42.8 percent of 33- year-olds return to prison within three years. Using figures from 1992, when 15,870 inmates were released from prison, the authority's analysis concludes that truth in sentencing, by increasing the average age of release, could have prevented the return to prison of 333 people who served time for crimes against persons, 326 drug offenders and 84 sex offenders. Even so, the authority's study also projected that nearly 1,500 violent criminals, almost 1,400 drug offenders and 180 sex offenders would return to prison within three years, convicted of a new crime notwithstanding truth in sentencing. Moreover, the report notes, the truth in sentencing "would have very minimal effects on reducing recidivism rates for property offenders." The authority's projections indicate that of the 6,389 persons released in 1992 on property offenses, truth in sentencing would have prevented the return to prison of just 102 of them. So, while truth in sentencing might keep 845 ex-inmates from returning to prison in a given year, it would have no effect on another 6,450 who might be expected to commit new crimes and be reincarcerated. Meanwhile, the cost of truth in sentencing would be extraordinary. The Department of Corrections estimates that the proposal would nearly triple the current inmate population over 10 years, necessitating construction of 28 new 1,600-bed prisons. The cost to build them would be $1.5 billion. The cost to operate them would be $4.3 billion over a decade. Maybe, says Donald Dripps of the U of I, "the most practical thing would be 'truth-in-crime legislation.' Maybe every time you pass a tougher sentencing law you'd have to pass the taxes to pay for it."

"The passage of laws is one thing people do because that is one thing they can do," says Michael Smith. "Building prisons is another." Smith is president of the Vera Institute in New York City, a not-for-profit center that researches and develops new techniques for policing and sentencing. He says he was long puzzled "why politically accountable officials weren't held to political account for the failure of their remedies, until I realized the people are not demanding remedies, but only demanding action. "If you are a chief executive, or a legislator or a high-level bureaucrat, your power to touch the moment and instance of crime is almost zero. What you can do is appropriate funds and build concrete and steel. So while a politician won't promise a 20 percent decrease in the burglary rate, he can promise a 20 percent increase in the number of prison cells. But you can't threaten teenagers, who think themselves immortal, with a prison cell they don't think they'll ever see." "There is no magic answer," says Prof. Leipold from the U of I. "People commit crimes for a zillion reasons their economic situation, to feed an addiction, because they're angry at someone, greed. The sources of crime are so numerous that people who look for a program or a simple solution are kidding themselves." 22/August 1994/Illinois Issues

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||