By JENNIFER HALPERIN

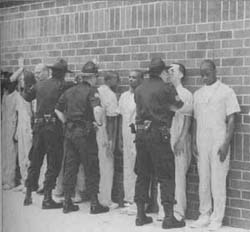

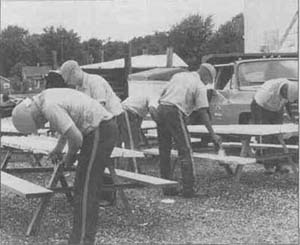

It's not every day one sees a grown man cry, let alone several. Especially men born and raised in some of Chicago's toughest neighborhoods; men with histories of drug use, gang involvement and bullet wounds. Men who have seen brothers and friends killed. But this is a fairly common sight at Illinois' Impact Incarceration Program — better known as a boot camp — in Greene County, about 50 miles southwest of Springfield. A lot of tears are shed during inmates' first few days there, and it's easy to see why. During a participant's first hour, the camp's officers are in his face screaming nearly non-stop. In scenes reminiscent of military movies like Full Metal Jacket, the incoming inmates are bullied and insulted to the point that tears start flowing. "You see a lot of crying the first few weeks," says Lt. Scott Lancaster, who has worked at the boot camp since it opened in March 1993."For a lot of them, it's the first time there's been any discipline in their lives." The state's first boot camp for prisoners opened at Dixon Springs in October 1990. A third one is set to open in August at DuQuoin. In Illinois, boot camps are a prison alternative offered on a voluntary basis to first- and second-time offenders who are under 36 years old and face up to eight years in prison. A boot camp sentence is 120 days, with extra time tacked on for mis-behavior. August 1994/Illinois lssues/23 Most of the inmates are young black high school dropouts from urban neighborhoods. They're not used to taking orders from people, Lancaster says, or asking for permission every time they wish to speak. Or rising at 5:30 a.m. for a regimented day full of grueling exercise and physical work. Or spend- ing their time cleaning up flood debris in 90-plus-degree heat, or painting buildings and mowing lawns in small southern and central Illinois towns. By subjecting inmates to such rigors, boot camps have been perceived as being "tough on crime," a label that has helped spur public and governmental approval for them. Their numbers have exploded in the past 10 years: While just two states had the programs in 1984, there now are more than 50 camps in 30 states, run by local, state and the federal governments. But political enthusiasm can carry them only so far. The camps have been running long enough that their results can be assessed, and studies are showing there's cause for concern about their perceived success. Boot camps were supposed to reduce prison crowding and costs by providing a cheaper alternative, and to deter crime by instilling discipline among participants. But across the country, boot camp graduates are returning to prison at roughly the same rate as those serving time in traditional prisons. In Illinois, the rate has been judged a bit better, and the state has been credited with taking steps toward keeping boot camp inmates' recidivism rates relatively low. Even so, nearly half of those who graduate from the state's boot camps end up returning to prison. Researchers have suggested ways to improve these numbers — more extensive job training in boot camps, for example, or more comprehensive followup drug treatment — steps that cost money and may be difficult to implement. But without improvements boot camps likely will continue serving their purpose — reducing costs and deterring crimes — for only a portion of those who graduate from them. To a visitor, the Greene County boot camp looks like the kind of place capable of turning young offenders' attitudes around. For one thing, the inmates keep it spotless. During work hours, they're constantly dashing around mopping, dusting and polishing just about everything in sight. They excuse themselves every time they pass a staff member or visitor in the hall. They ask for permission every time they want to speak. Their days begin with a 5:30 a.m. wakeup. Then there's physical training, showers, breakfast and inspection before work crews are sent out at 8:45 a.m. Some work inside the camp, cleaning and landscaping, and others are sent to nearby towns. On the crews, the camp's strict discipline carries through — no talking, no goofing off. There's a half-hour lunch break, then back to work until 3:00. After that, there's more exercise, another shower, dinner, classes toward a G.E.D., a high school equivalency diploma, and drug counseling for those who need it, which is just about everyone. Lights go out at 9:30 p.m. Inmates' only free time is between 1:30 and 2:30 p.m. on weekends, and most attend the non-denominational religious service offered during that time on Sundays. This rigid schedule works well for the camps, says Ernest Cowles, an associate professor at Southern Illinois University who conducted a study on boot camps for the National Institute of Justice. "Boot camps seem to have few problems controlling discipline, even less than in low-security prisons," he

says. "They have value in reducing inmate unrest. And we should look at them as models for ways to reduce idleness in prisons, which is something the public doesn't want to see." But many inmates can't take the strict discipline and drop out of the program, opting out even though they will have to serve out much longer sentences in prison. Nearly one-third of those who begin the boot camp programs fail to finish. A Department of Corrections study presented earlier this year to the governor and General Assembly found that through 1993, 1,386 (64 percent) of the 2,169 boot camp inmates graduated. Of the 783 who dropped out, three-fourths quit voluntarily, generally because they found the camps' physical training, work details and intensive staff supervision and authority too demanding, according to the report. The others were forced out because of repeated rule violations or based on mental or physical health considerations. Despite the large number of dropouts, there doesn't seem to be much public discussion about a punishment level between boot camps and minimum-security prisons. "If a person is not properly motivated to do better in boot camp, I'm not certain we should find some easier way for them," says Howard Peters III, director of Illinois' Department of Corrections. "The people who aren't motivated are the people at higher risk for recidivism." For inmates who do stick it out, about three in five seem capable of living completely crime-free after they graduate. One recent graduate who might be among those is James Jones of University Park, south of Chicago, who graduated in June from the Greene County boot camp and insists he learned lessons there that will keep him away from crime. Jones, 31, was found guilty of possession of narcotics and was offered a choice between five years in a state penitentiary and 120 days in the boot camp. He selected boot camp, thinking it would merely be the quickest way back to his wife and three kids. But while serving his sentence, Jones says, he realized he should use the time to set some kind of positive role model for his children, ages 11, eight and four. As part-owner in a jewelry store and a motorcycle repair business, he never felt the need A 24/August 1994/Illinois Issues to finish high school, which he left in his senior year. But in boot camp, he pursued and received his G.E.D. "I honestly don't feel like I need it, still. But I started thinking I better do it for my kids, to show them education is what they need," he says. "That's the only reason I did it." Lt. Lancaster points out that inmates' normal lives usually lack anything close to the demanding rigidity of the camps. "We try to give them a sense of accomplishment," he says. "By finishing a program as difficult and demanding as this, it gives them something to be proud of." And for inmates who have children, Lancaster says, officers also emphasize the importance of setting a law-abiding example for others. "I tell them if this generation doesn't stop and change things, I'm going to be sitting here and be talking to their kids in a few years," he says. This type of inmate — one who's a little older than the average 21 years, and who is leaving boot camp with a family, a high school education and a job in place — can benefit from the program, says Cowles. The discipline, education and drug treatment the camps offer may be enough of a kick in the pants to straighten up someone who gets into place a framework for crime-free self-sufficiency — namely, a job and an education. But the boot camp approach is not so promising for everyone. Seventeen percent of those who graduate from the Illinois programs return to prison for new felony crimes, compared to 26 percent among ex-convicts with similar criminal histories who served time in traditional prisons. Another 25 percent of the Illinois graduates end up returning to prison for technical violations of their probation, such as missing a curfew. Figuring in the number who have dropped out, just one in four Illinois inmates originally admitted into the program has stayed out of prison completely. One in two has avoided returning for felony crimes. Why are those numbers so discouraging? First, not every inmate can break free of gangs, which have been the center of their lives on the street. Lancaster says that despite the camp's strictly enforced standard outfits, haircuts and supplies, some inmates find ways to make themselves different to signify gang loyalty. As Lancaster shows a visitor through the boot camp's dorm rooms, an inmate stands at attention. His shirt catches the lieutenant's attention; its tucked-in collar and closed top button deviate from the norm at the camp. He grabs the inmate's shirt collar and yanks the top button off, demanding the inmate fix his outfit and his attitude. The response is a hearty, "Yes, sir!" Lancaster worries whether some inmates will be able to avoid gangs and their criminal activities after they leave the boot camp. Even among those who seem to want to change, he says, their home environments can lure them off track. Take, for example, Danny Grant, an 18-year-old from Chicago's south side who was arrested for possession of marijuana and cocaine. Although he was in the 11th grade when he dropped out of DuSable High School, a boot camp assessment on academic preparation placed him too low to train for the G.E.D. He's getting some basic education training, but will leave the boot camp with no diploma, no job — and basically no ticket out of the lifestyle that lured him into crime in the first place. "Instead of going out and getting back with gang-bangers I'm going to stay away," Grant says while on break from his work crew job cleaning streets in tiny White Hall, near the Greene County boot camp. "I was dealing drugs because when you've been around people your whole life who did it, you do it. Here you learn to better yourself, be responsible for yourself. It ain't hard to find new people to hang around with. I'm not going back to be in crime." He may be right. Grant may be able to leave the boot camp, return home, find a job and steer away from drugs and crime. But he faces some severe obstacles to doing so — the same ones that landed him in the boot camp. Obstacles such as an inadequate education, no job and peers who turn to gangs for money and security. "I think they feel they're going to make it," says Lt. Jeff Bates, who supervises the camp's work crews. "But they're going back to the same environment they came from, and it's hard. If you come from a ghetto or the inner city, and you go back out even after this type of thing, you're still facing the same things out there." Cowles agrees. "In general, younger offenders don't have much internal structure," he says. "It has to be imposed from the outside, and then they fit into it fairly well. It's when they're released and have to take over disciplining themselves that things like having a job, having a G.E.D. can help get them back into some stability." National studies have credited Illinois for its efforts to help boot camp inmates stay out of prison once they've been released. An evaluation done for the National Institute of Justice found Illinois was one of the three states with boot camps that showed any evidence of reducing recidivism. In Illinois and Louisiana, wrote Prof. Doris Layton MacKenzie of the University of Maryland, boot camp graduates were less likely to be returned to prison for a new crime but more likely to return for "technical" violations, such as missing a curfew or failing a drug test. Illinois requires inmates to spend 90 days on electronic detention before they are transferred to regular parole. When the Dixon Springs boot camp first opened, inmates also had to spend at least 90 days on intensive supervision. That requirement was removed after a study by the state's Department of Corrections found that more serious offenders needed the close supervision more than boot camp graduates. The state also requires that inmates either work, go through job training, continuing education or drug treatment programs, or perform community service for 40 hours a week while they're under supervision; they cannot sit idly at home. Requirements such as these are good, MacKenzie notes in her NIJ study, but would be enhanced by additional efforts. For instance, flexibility in the after-care component at boot camps — during which one in four Illinois boot camp graduates return to prison — could reduce recidivism more, she notes. If one major goal of boot camps is to reduce prison crowding, it may be counterproductive to send inmates back to prison for a single positive drug test or missed curfew. In cases of single positive August 1994/Illinois Issues/25 drug tests, for example, an alternative to prison might be to extend those boot camp graduates' community service status and lengthen the time they're required to spend in drug counseling. But Peters says stringent requirements make it clear to graduates that no slips in lawful behavior will be tolerated. "When you have a structured program like this, you want the graduates to follow something very structured when they get out," he says. "We hope to be able to reduce the numbers [of technical violations], but we don't see it as all bad if people return to prison for something that doesn't involve a new victim." Another point MacKenzie makes is that while short stays at boot camps may be good for reducing prison crowding, they do not always allow enough time to deliver sufficient drug treatment, long-term education, or job skills. She questions whether boot camps prepare graduates for employment. "Contrary to popular opinion," she writes, "it is unlikely that the long hours of hard labor characteristic of [boot camps] will improve work skills or habits. The labor that is often required of... participants is largely menial, consisting of picking up trash along highways, cleaning the facility or maintaining grounds. It appears unlikely that it will be of much value in and of itself." But Peters says boot camps try to teach "job readiness skills" rather than specific training. "A lot of people don't lose jobs because they don't know how to do the work," he says. "It's because they don't have a work ethic. We're trying to teach proper work attitude. Many of them have never held a job, never responded to supervision, so we have to teach them how to do that." Lancaster says some employers are impressed by the hard work required at the camp, and that one employer hired someone based upon his boot camp experience because "he said he knew this guy could really do some hard labor." By and large, though, the short stays hamper ideal education and job-training efforts, says John McCorkle, superintendent of the Greene County boot camp. "I really wish there was more we could do for the kids once they've left," he says. "I would like to see some type of vocational training, maybe an apprenticeship program, because some of these kids have no skills at all. But in four months time, there's really nothing we can do on that. We're just trying to get the basics across to them — stress education, begin drug counseling and try to get them to feel some self-respect." There's no guarantee, though, that these basics will take a person very far. "With a 120-day stay, the likelihood is a person's not going to develop long-term change," Cowles says. "The high-visibility part of the boot camp is when the public sees offenders in there with a drill sergeant barking orders, and we think, 'OK, they can straighten them out.' But lifestyles don't evolve overnight.

"You need a program with structure and support so changes during programs can be continued," he says. "I think they need to be developed into longer stays, whether longer stays in the boot camps or more continuation in community service. I think Illinois has the things it needs in place; there's just a lack of resources to provide everything needed." Peters says he also wants to see the state's post-release program expanded. "I think we are doing some of the right kind of things in requiring them to participate in school, work, public service, but I think we can strengthen what we do," he says. In the coming year, he says, the department will be looking at implementing more specific, structured activities; one idea is to begin daily job training and drug treatment at one location that graduates would take part in as a group. The value of boot camps as they now exist seems limited. Their numbers so far show they're keeping about one in four of those who start the program from returning to prison. Among those who have studied the programs, the ways to possibly improve that ratio include: • Lengthening in-camp sentences or post-release mandatory supervision so education and drug rehabilitation efforts can be expanded. • Instituting work training programs in the camps, geared toward teaching inmates skills in a specific trade that may help land a job. • Rethinking the policy of returning inmates to prison on technicalities, which has inflated recidivism rates significantly in Illinois. "The more services we provide, the more we help maintain the changes made in boot camp," Cowles says. Following some of these suggestions could help Illinois increase the chances of the Danny Grants of boot camps, who may not have much more than a will to improve when they return home. Otherwise, the state's get-tough boot camp approach — for all its media appeal, political support and ability to scare even society's toughest young people to the point of tears — will continue wasting money and time on many people who only wind up back in prison. 26/August 1994/Illinois Issues

|

|||||||||||||||