By JENNIFER HALPERIN Political polarity

You couldn't find two more opposite candidates to run for secretary

of state if you asked Hollywood to cast the race

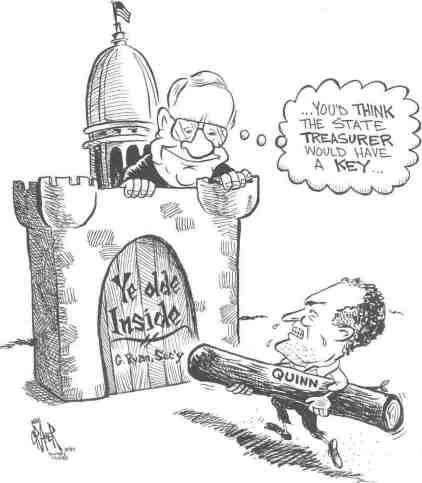

It was a warm day in mid-May, and Elsie Turner was worried her chocolate chip cookies were going to melt. She'd baked them special for the one politician who had captured her interest and loyalty of late — state Treasurer Patrick Quinn, the Democratic candidate for secretary of state — so she wanted them to stay intact. Elsie and her husband Jim aren't exactly big fans of many public officials; in fact, they think most are dishonest and untrustworthy, and would just as soon see them kicked out of office. The Turners are the kind of citizens so frustrated with government that they eagerly signed on with United We Stand, Ross Perot's alternative to the Democratic and Republican parties. They're also the kind who embraced Quinn's term limits petition drive with a vengeance; the Turners collected 15,000 signatures in their zeal to see the measure placed on the ballot. They see Quinn as a different breed of politician. "From the first time I heard him on the radio on KMOX, I thought: 'This guy is too good to be true,'" Elsie says. "Just everything he talked about — term limits and giving power back to voters — I totally agreed with." So when she heard Quinn was going to be in Decatur appearing at a local school and doing some TV and radio interviews, she and Jim volunteered to chauffeur him around town. Which is how she came to be sitting in a hot car, waiting for him, and worrying about her cookies. Quinn must be thrilled to have friendly, enthusiastic supporters like the Turners. Because in the political world, this kind of support seems to be just about all he's got. He's earned the hatred — yes, the feelings of some appear to run that strong — of too many political insiders from both parties to be able to count on them for help in passing legislation, raising money, winning elections, or much else. October 1994/Illinois Issues/17 The irony of this race is that Quinn is running against a man who may well be his political antithesis. George Ryan is well- liked by both Republican and Democrat lawmakers — or at least liked enough that he can guide his proposals through the legislature, for example, while similar bills pushed by Quinn sit idle. While Ryan worked his way up through the Republican ranks by serving in various political offices, Quinn gained fame as a voice of protest against the political establishment. In many ways, it's doubtful that two more opposite candidates could have been invented for this race. If Ryan and Quinn were running solely on their records in the offices they currently hold, it would be difficult to pick a If Ryan and Quinn were running solely on their records, it would be difficult to pick a winner. Both have done arguably well in their respective positions winner. Both have done arguably well in their respective positions. As secretary of state, Ryan has aggressively encouraged people to sign up as organ donors, leading to a 50 percent increase in the number of driver's license applicants who signed up. There were 1.5 million registered donors in Illinois in July, more than any other state, Ryan says. He also has backed literacy efforts; since he took office, funding for workplace literacy grants have nearly quadrupled. And Ryan was behind the lobbyist registration and disclosure law — the only successful ethics reform the legislature has passed in recent years. As treasurer, Quinn has helped young children set up bank accounts through their elementary schools as part of the two- year-old Bank at School program. Students learn about loans, mortgages and other financial transactions, and are encouraged to start saving through participating banks that link up with classrooms. Quinn also has fought for lowering currency exchange fees that take a toll on the poor, and has tried to increase bank loans for housing, small businesses and agriculture by depositing state money in banks that are generous in these areas. But their records in office will be just one of many factors in deciding the race in November, and perhaps not the most important factor. First, other than the fact that the secretary of state's name is on their driver's licenses, many people know little about the duties of the office. At the same time, candidates are usually spurred to run for the office by more than a desire to be the state's chief librarian, another of its functions. The secretary of state oversees about 3,500 jobs, and guarantees its holder very high name recognition. It can be seen as a stepping-stone to higher office — as it was for Gov. Jim Edgar and former U.S. Sen. Alan J. Dixon. So, much is at stake in this race, and each candidate brings a wealth of political experience to his run for what is arguably the state's second most important statewide office. George Ryan worked his way up through the Republican ranks to his current position by serving for more than a decade in the legislature — including four years as House GOP floor leader and two years as speaker — and then two terms as lieutenant governor under Jim Thompson. Ryan likes to reminisce about his days as the last speaker of "the big House" when he presided over a House of Representatives with 177 members — before Quinn's Cutback Amendment reduced the size of the House by a third. In collecting signatures to get this amendment on the ballot, and in campaigning for its approval by voters, Quinn made a name for himself as someone who wanted to take politicians off the public payroll. He also earned the enduring enmity of many politicians. In contrast, Ryan is the politician's politician. A testament to his image as the consummate political insider is that he's maintained so many friends in both parties. One reason for these allegiances is that he can't be painted as an extremist. Five years ago, for example, while serving as lieutenant governor, Ryan irked conservatives in his party by enthusiastically supporting a failed effort to ban assault weapons. The move put him in an unlikely alliance with some of the most liberal Democratic members of the legislature. And two years ago, when almost everyone under the Capitol dome was pushing their own ethics-related measures, only Ryan was able to successfully maneuver his into law. It wasn't the boldest proposal in the world — it did nothing, for instance, to sever ties between campaign contributors and recipients of state contracts — but it provided just enough bite to satisfy those who were clamoring for some kind of reform that year. Scores of other ethics proposals went nowhere. Quinn, meanwhile, not only prides himself on having so few political friends, but seems hell-bent on reducing that number. One of his main missions has been to cut down the perks and power that accompany political office. For example, in 1976 he stirred up so much public anger over the fact that lawmakers received their entire annual salary on their first day in office that the legislature voted to end the century-old practice. A few years later, when the legislature raised the salaries of all its members by $8,000, Quinn urged citizens to send teabags to the governor's office as a Boston Tea Party-style protest. When nearly 40,000 teabags glutted the governor's mail room, a special session of the legislature was called, and a portion of their raise was delayed for a year. This year, Quinn has continued building on this "outsider" image by pushing for an amendment to the state constitution that would limit Illinois lawmakers to eight years in office — a prospect that irritates and frightens many entrenched politicians. In their battle for secretary of state, Ryan and Quinn have so far been true to their public images. For the most part, Ryan has spent the past few months trying to build his likable image as a guy who does good, if somewhat safe, things with his office — like getting tough with teen-aged drunk drivers, and successfully promoting legislation requiring criminal background checks for school bus drivers. Ryan has issued I8/October 1994/Illinois Issues

detailed position papers on issues like improving customer ser- vice for driver's licensees, highway safety and literacy — all areas that have to do with the secretary of state's office. He is stressing his ability as a steward of good government. On the other hand, Quinn has continued trying to project himself as an organizer of the masses against the rich and pow- erful, even in an office like secretary of state. "I think the secretary of state's office is like the Chicago post office," he says. "It works for the office-holders, but it's inefficient and wasteful for too many people. I know how to organize customers. I organized the Citizens Utilities Board to change utilities; I can reorganize people who drive cars. There are defects in cars, problems with marketing cars and insur- ance of cars. The way car drivers are treated by the tollways is bad. I know they'll say this has nothing to do with the secre- tary of state's office, but I think it has everything to do with it. I think the secretary of state should be head of Citizens for Auto Reform." He's spent even more time trying to portray himself as the opposite of Ryan, whom he characterizes as the quintessential insider politician, or, as he puts it, "King George, prince of perks." Quinn has tried to capitalize on the image of pampered politician vs. working man at every chance. Whereas Ryan has seven bodyguards — more than any secretary of state in the country — Quinn has none. While vehicle title and registration taxes were increased during Ryan's tenure, Quinn vowed to cut each of the fees by a dollar per year over the next four years. Charging that Ryan billed taxpayers more than $12,000 for lawn care and snow removal at his Springfield residence, Quinn showed off Sears and Kmart circulars at a press confer- ence, pointing out ads for lawnmowers that Ryan might take a look at. Combing the Sunday papers for good deals, Pat Quinn is just an everyman who happens to hold state office, right? A true outsider. Well, that's an assertion that riles Ryan and many others who have watched Quinn over the years. "He's as insider as anyone," Ryan says. "He was back working for the Dan Walker administra- tion [in the 1970s]. He's made a career out of push- ing referenda. I don't think he's held any job out- side the public eye." Many people share Ryan's opinion. The most common description you hear of Quinn isn't "common man"; it's "demagogue." "Years ago, I used to look at Pat Quinn and think, 'Now here's a guy who really wants to do things differently,' and I thought that was pretty neat," says a longtime Statehouse journalist. "But it got to the point where he just kept demagoguing on all these issues, and you start to think he's just like everyone else. He used to say he was working on public policy issues for the public's good, and that he absolutely didn't want to run for public office. Now we see he's just a regular politician." The funny thing is that people have had the same complaints about Quinn for more than a decade. An Illi- nois Issues story from February 1980 titled "Pat Quinn — a man politicians love to hate," details, among other things, his history as a "ghost payroller" in former Gov. Dan Walker's administration, when he pulled a salary from one agency but did not work full-time there. He also handled patronage for Walker. Filled with angry quotes from politicians and political observers calling Quinn a hypocrite and asserting he's no more of an "outsider" than those he attacks, the story reads like it could have been written today. Quinn responds to such criticism now much as he did then. "I see myself as someone who helps organize the public about issues," he says now. "Anytime you do this there will be a modicum of cynicism among institutions — from lobbyists, from career politicians, even from reporters. The press is an institution. I deal with cynicism all the time. These institutions don't understand that idealism still works. You have a cause and you know it will help people. So I don't really care what institutional folks say." Quinn isn't necessarily saying his critics are wrong — only that they have an ax to grind. And so does he. His most credi- ble claim to the title "anti-politician" is in his willingness to make powerful people angry; he doesn't shy away from an issue — like term limits — if it will boil the blood of people who control campaign contributions. Instead, he embraces it. And that's enough of a difference from the norm for people like Elsie Turner. "I really believe he wants to change things," she says, "and I don't think many others in public office truly want that." The easy part for Quinn has been projecting his outsider image to cynics among the public; the hard part seems to be expanding it to a larger audience of those casting ballots. Ryan, on the other hand, hopes voters won't buy the idea that Quinn is a political outsider inside the government. October 1994/Illinois Issues/19

|

|||||||||||||||

George Ryan

George Ryan

Pat Quinn

Pat Quinn