By MARK BROWN

|

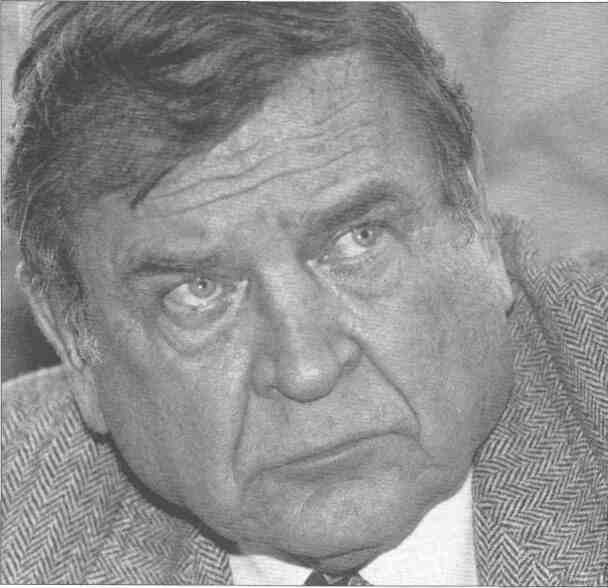

This much seems clear: The man who could go down in Illinois history as one of its most crooked politicians also deserves recognition as one of its most accomplished

Photo by Bill Stamets

|

12 / December 1994 / Illinois Issues

Rosty

The clout is gone

At the end, Dan Rostenkowski didn't seem any more powerful than any other member of Congress as he stood on a Chicago beach last month and promised to score a couple hundred million federal dollars to save the Lake Michigan

shoreline from erosion.

It was exactly the kind of made-for-television appearance on which Rostenkowski had been relying during three years of re-election campaigning: a photo opportunity to remind the voters of his singular ability to bring home the bacon.

This time, however, instead of bragging about his latest multi-million dollar coup, the 18-term Chicago Democrat was

reduced to talking about what he might be able to do in the future, if he got the chance, just like a lot of politicians of more ordinary reputation.

It's now known he won't get the chance. Mortally wounded by a 17-count federal indictment and the resulting loss of his House Ways and Means chairmanship, Rostenkowski was tossed aside November 8 by voters in his 5th Congressional District in favor of Republican Michael P. Flanagan.

Perhaps they sensed that Rostenkowski had become what one local political adviser described as a "dinosaur still trying to roar" instead of the legendary figure that had been sold to them in recent years: a contemporary Paul Bunyan who seemingly scooped out Chicago's Deep Tunnel with a broken beer bottle and resurfaced its

Kennedy Expressway with asphalt pried with his bare hands from the runways of Washington's National Airport.

More likely is that the voters weren't as cynical as the parade of Illinois officeholders who found his booty reason enough to overlook the indictment and to evoke his presumption of innocence in the face of allegations he stole nearly $700,000 from taxpayers through a variety of chiseling schemes.

While the legend of Dan Rostenkowski won't be complete until that criminal case is resolved, it's not too early to assess what he has meant for Illinois and what his loss will mean to the state's future.

This much seems clear: The man who could go down in Illinois history as one of its most crooked politicians also deserves recognition as one of its most accomplished.

Rostenkowski was vitally important in helping Chicago and Illinois compete for federal dollars, and his departure from

Congress will hamstring Gov. Jim Edgar and Mayor Richard M. Daley in their efforts in Washington. Daley can probably

start by kissing the shoreline protection money good-bye.

But some of the projects Rostenkowski aided were more vital to the politicians and other friends he assisted than to the residents of Chicago and Illinois. Rostenkowski, always the dealmaker, at times seems to have brought home federal funds for the simple reason that he could, not out of any personal conviction that they were needed.

Some may see his pork-producing proclivities as an example of what's wrong

December 1994 / Illinois Issues / 13

with Congress. Such practices, however, aren't likely to go away just because he does, even in the new Republican-controlled House and Senate. The only difference is Illinois won't get as large a helping.

Former Illinois Sen. Alan J. Dixon, who also devoted himself to pursuing pork, offered one of the most enthusiastic testimonials for his old colleague.

"I was there 12 years, and he did more for Illinois every year than the other 21 [House members from Illinois] put together.

|

Edgar, who struck up a personal friendship with Rostenkowski, will be one of the sorriest to see him go

|

I was there, and I know. In the whole Senate and House, there aren't a half dozen people that can do what he can," gushed Dixon, who is now in private law practice.

There is no shortage of such praise for Rostenkowski, despite what he euphemistically refers to as his "problem." It comes from politicians of both parties.

Gov. Edgar, who struck up a personal friendship with Rostenkowski, will be one of the sorriest to see him go.

Rostenkowski endeared himself to the governor in Edgar's first year in office in 1991 by intervening with George Bush's administration to help preserve a Medicaid financing plan on which Edgar was relying to solve a budget crisis. The congressman saved the state hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. There have been many millions more since then.

To assess the importance of Rostenkowski to Chicago and Illinois, it's a good idea to take a look at The List. Formally

titled "Accomplishments of Congressman Dan Rostenkowski on Behalf of the Chicago Metropolitan Area (Partial List)," The List is precisely that a 15-page recitation of pork-barrel goodies and other valuables for which Rostenkowski takes credit.

There are 144 entries, beginning with $2 billion for the Deep Tunnel and ending with $1 million in security assistance

from the Department of Defense for last summer's World Cup soccer matches in Chicago. In between is everything from his much ballyhooed garnering of $450 million for the recently completed Kennedy rehab project to a little-noticed $2 million grant for DePaul University's John T. Richardson Library.

Behind most of those list entries is a story of how government works, stories that Rostenkowski himself likes to tell

over a steak dinner with his buddies, or occasionally with the press, although he often precedes the latter sessions with a threatening, "This is off the record."

One such story involves how Rostenkowski helped secure for the city of Chicago the right to tax passengers flying in and out of its airports.

The tax, originally intended to raise money for the construction of a third airport, now yields $90 million annually for

improvements at O'Hare and Midway airports. But its passage was in big trouble before Rostenkowski stepped in to salvage it. According to Ways and Means lore, he threatened to hold up the entire federal budget at one point until he was sure the tax was in place.

The impediment to the deal was Sen. Wendell Ford (D-Ky.), chairman of the Senate aviation subcommittee, a wily

politician in his own right. The airport tax had been shepherded through the House by another Chicago Democrat, Rep.

William 0. Lipinski, but when Ford blocked the measure in his committee, the call went out to Rostenkowski to supply the grease to cut the deal. Rostenkowski brought Ford in line by reducing a planned increase in the cigarette tax, something the tobacco state senator was seeking. Rostenkowski also helped pave the way for the resolution of another Ford concern: allowing the federal government to pre-empt local airport noise regulations, a move sought by Ford to protect Federal Express.

Then there is the story of the Chicago Theater, a project that didn't even make the congressman's list of accomplishments.

As one of Rostenkowski's former aides tells it, Chicago officials and a group of private developers were awaiting

approval during Ronald Reagan's presidency of a $2.5 million Urban Development Action Grant to restore the theater. The coveted federal funding was to be used to remodel the venerable State Street movie house into a theater for live music shows and plays.

Housing and Urban Development Secretary Sam Pierce had spiked the project to get Rostenkowski's attention. Pierce was miffed that the Ways and Means panel had bottled up federal enterprise zone legislation that the Reagan administration was seeking, and he figured Rostenkowski would call him looking to make a deal.

Instead of calling Pierce, however, Rostenkowski called his friend, then-Vice President George Bush, and told him to

straighten Pierce out, no doubt with a reminder of some other matter of greater importance to the president that needed the Ways and Means Committee's approval.

Shortly thereafter. Pierce phoned Rostenkowski to ask if he could come up and see him. Sure, the congressman replied, just bring the papers for the theater project.

Pierce did as he was instructed and when the deal was complete, he asked Rostenkowski if the Ways and Means Committee would schedule hearings on the enterprise zone bill.

Naturally, Rostenkowski refused.

Both stories illustrate the keys to Rostenkowski's influence: He held a position of enormous power as Ways

and Means chairman, he has forged relationships with other powerful people during more than three decades in Congress, and he wasn't afraid to use his power to make things happen.

The combination of these factors allowed him to be known as a man who was going to be in the room when the big decisions were made, not the type of congressman who thinks he can protect his constituents' interests by signing a letter along with five of his colleagues.

14 / December 1994 / Illinois Issues

Rostenkowski had put together a fairly undistinguished career in Congress until 1981 when he took over

the Ways and Means panel the committee responsible for writing all tax legislation.

"It's an incredible position to have leverage on," said William Daley, a lawyer with Mayer Brown & Platt and brother to Chicago's mayor. "Everybody's coming to Ways and Means."

In the first place, most important pieces of legislation receive consideration from Ways and Means at some point, allowing Rostenkowski to make a direct imprint. But beyond that, other committee chairmen or cabinet officials knew they had to deal with Rostenkowski on matters that didn't come directly to Ways and Means because they would certainly be handling something else that would.

But there was more to Rostenkowski's influence than the chairmanship, which others have handled less adroitly. He has fancied himself a confidante of presidents and has indeed established himself as such. There also are relationships with cabinet members and congressional colleagues, all of whom are familiar with Rostenkowski's penchant for rewarding his friends and punishing his enemies.

"He's got all these relationships built up over 37 years and that counts for so much down there," said Daley, whose law practice has included lobbying the Ways and Means chairman for clients in private industry.

|

Nobody owes more to Rostenkowski than the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, which is digging the Deep Tunnel to relieve flooding problems

|

|

Republicans even score in congressional delegation

The GOP went into the election with eight U.S. House seats to the Democrats' 12. When the polls closed they were tied 10-10.

Newcomer Michael Flanagan knocked Rostenkowski off his 5th District seat in Chicago. But Rostenkowski, long-time chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, was already wounded by legal troubles. He was indicted last May on 17 counts ranging from trading stamps for cash to padding his payroll with no- show workers. Flanagan, a 32-year-old lawyer, got last-minute cash from the GOP.

The Republicans also picked up the 11th District seat after the retirement of Mokena Democrat George E. Sangmeister. And they held onto the hotly contested 18th District seat vacated by Republican leader Robert H. Michel of Peoria.

The 11th District, including Joliet, is considered a swing district. Jerry Weller of Morris beat Democrat Frank Giglio. In the 18th District, Michel aide Ray LaHood beat Democrat Doug Stephens.

In other closely watched races:

William O. Lipinski beat back his challenger in the 3rd District.

Mel Reynolds, despite an indictment on sexual assault charges, easily aced several write-in challengers in the 2nd District.

Both districts are in Chicago.

Illinois retained some seniority on both sides of the aisle, notably Republicans Henry Hyde, John Porter, Phil Crane and Harris Fawell; and Democrats Sidney Yates, Cardiss Collins and Dick Durbin. But political scientist Jack Van Der Slik of Springfield's Sangamon State University says the loss of two "heavy lifters" in Michel and Rostenkowski will have an impact on the state's ability to go to the table in Washington over the next two years.

|

Terri Moreland, the state of Illinois chief lobbyist in Washington, recalls an incident just before Christmas 1991 when the state got word that funding for an upgrade of Fermilab had been eliminated in Bush's soon-to-be-released budget. The cuts would have resulted in 100 layoffs and threatened the lab's position as a leader in high energy physics, Moreland said, so she tried to get the money restored before the president's budget hit the streets, after which it would be an uphill climb. While House Minority Leader Robert Michel was asked to make the case to Bush, it was left to Rostenkowski to work on Budget Director Dick Darman, with whom he had tangled previously on the Medic-aid business. Darman had gone on vacation for the holiday, but Rostenkowski tracked him down, and the Fermilab jobs were saved.

"I remember being told there's probably only a handful of people in the world who could get through to Dick Darman when he's on vacation," Moreland said.

Nobody owes more to Rostenkowski than the folks who run the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, the agency that is digging the Deep Tunnel to relieve flooding problems in the Chicago area.

It is one of the most mammoth public works projects in the nation and long a priority for Rostenkowski.

Every year, recalls former aide Thomas Sneeringer, Rostenkowski would prepare a wish list for Rep. Tom Bevill (D-

Ala.), chairman of the House Appropriations subcommittee that oversees water projects. "He would say, 'Don't forget, Tom. Deep Tunnel is first priority. If I don't get anything else, I want that.'" And when Congress decided several years back that the federal government should only pick up 50 percent of the cost of water projects instead of the 75 percent it had been paying, Rostenkowski grandfathered in the old funding formula for the Deep Tunnel so that the Water Reclamation District still gets its 75 percent.

Water Reclamation District President Thomas Fuller is grateful.

"He has been a real benefit to us, and when I say us, I'm talking about the taxpayers of Cook County," Fuller said.

December 1994 / Illinois Issues / 15

"That's the man who has gotten things done, in my opinion."

The project for which Rostenkowski takes credit that often draws scoffs is the reconstruction of the Kennedy Expressway, Chicago's crucial link to the north and northwest. Chicagoans are accustomed to the cyclical repaying of their expressways and don't figure somebody has to wave a magic wand in Washington to get it done.

But state transportation officials say that without Rostenkowski slipping through $225 million in special appropriations, the project would have been scaled back in size and taken twice as long as the three years in which it was completed.

"There aren't the funds in the normal course of business to handle it," said Illinois Department of Transportation spokesman Dick Adorjan.

Next up on the IDOT drawing board is a remake of the Stevenson Expressway, but Adorjan said there is a "serious concern" about where the state will find the money without help from Rostenkowski. (Interestingly enough, Rostenkowski was miffed that Edgar officially reopened the Kennedy during a re-election press stunt without arranging for the congressman to be there.)

The effect of Rostenkowski's clout was measured in an investigation last year by the Orlando Sentinel, which found that Illinois, with $435 million, ranked fifth among all states in highway demonstration project (read pork barrel) money received since 1991. That was $ 131 million more than the state stood to receive if the money were allotted according to the federal highway aid system's normal formula.

Some of the demonstration project money is typical of what Rostenkowski's detractors see as the downside of

how he used his clout.

Take the $35 million that Rostenkowski earmarked for construction of an underground parking garage at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. Rostenkowski slipped it into the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act, acting upon a request by Mayor Daley, even though it wasn't on anybody's list of the area's transportation needs. Other city and state officials were aghast, especially when they had to come up with $8.5 million in local matching funds. The public benefit hardly seemed worth the cost. But in the end, local officials decided that getting taxpayers from California and Texas to pay most of the bill was too good a deal to pass up.

"For that $35 million to wind up on the drawing board for an underground parking garage that we don't think is needed, to us, it's just sort of a bad joke on the taxpayers," said Jackie Leavy of the Neighborhood Capital Budget Group, an organization that serves as a watchdog on the city's infrastructure spending.

Leavy's group also has no stomach for one of Rostenkowski's other big pieces of pork, Chicago's proposed

downtown trolley system known as the Central Area Circulator. The circulator, which also is on the endangered list with Rostenkowski's departure from Congress, carries an $800 million-plus price tag. That's too expensive for Leavy's organization, which would prefer he found more money for existing Chicago Transit Authority train lines. Both projects are symptomatic, Leavy said, of the congressman's blind willingness to pursue whatever agenda is set for him by local politicians.

"You can bring home the bacon, but if it isn't what nourishes the city, what's the point?" Leavy said. "You really have to ask yourself, 'Is this guy a leader? Is he good for the city?'"

Both the museum garage and the trolley are proudly included in Rostenkowski's accomplishments list, but not so for

another project that is often cited as a symbol of the dubious value of Rostenkowski's pork.

Presidential Towers, a mammoth luxury apartment complex just west of Chicago's Loop, was built before the congressman felt the need to draw attention to the spoils he brought to the city. Rostenkowski helped engineer a couple of special breaks for the developers, including a provision that allowed its construction to be financed with tax-exempt bonds without the normal restriction that a percentage of the apartments be set aside for low- and moderate-income tenants.

|

'You can bring home the bacon, but if it isn't what nourishes the city, what's the point?' Leavy said. 'really have to ask yourself: Is he good for the city?'

|

The apartment project helped revitalize a former Skid Row neighborhood but proved a financial bust. The developers

defaulted on a $159 million federally insured loan and are still negotiating with HUD officials on how to resolve their red ink.

One of the developers of Presidential Towers happened to be Rostenkowski's long-time investment adviser, Dan Shannon. Shannon subsequently became the trustee of Rostenkowski's blind trust, turning the congressman's initial $200 investment into a profit of more than $50,000.

The epitome of Rostenkowski's wheeling-and-dealing prowess was the 1986 Tax Reform Act. To win support for the

bill, Rostenkowski doled out billions of dollars in special interest tax breaks, known as transition rules. At least 41 of the 650 transition rules went to Illinois, including a provision that allowed for construction of the new Chicago White Sox stadium. Commonwealth Edison, John Deere, Caterpillar and 1C Industries all received valuable transition rules.

Not all of Rostenkowski's efforts on behalf of Illinois involve bringing in more federal funds. He also plays defense,

particularly for Chicago's futures industry. During both the Bush and Bill Clinton administrations, he blocked transaction taxes that were proposed as a means of funding the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. In a more controversial maneuver on behalf of the industry, he pushed through a special tax provision in 1984 that cut the legs out from under an attempt by the Internal Revenue Service to collect some $300 million from individual commodity traders who had used a tax avoidance device known as a "straddle."

16 / December 1994 / Illinois Issues

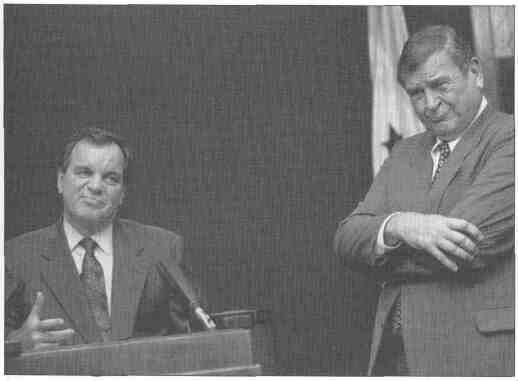

Photo by Bill Stamets

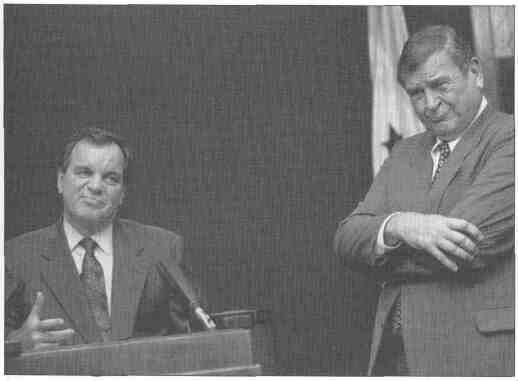

Dan Rostenkowski was vitally important in helping Illinois and Chicago compete for federal dollars, and his

departure from Congress will hamstring Mayor Richard M. Daley and Gov. Jim Edgar in their efforts in

Washington. In fact, a parade of Illinois office-holders found Rostenkowski's booty reason enough to overlook

the indictment and to evoke his presumption of innocence. Earlier this year, Daley (left) and Rostenkowski

faced the press in the mayor's City Hall briefing room.

A future without Rostenkowski is a frightening prospect for the futures industry, as it is for Daley and Edgar. But Chicago Board of Trade spokesman David Prosper!, somewhat downplaying the impact of his loss, said the CBOT has been assisted by Illinois' other representatives and senators and has successfully educated members of Congress outside the state on its issues.

There is more than a little resentment in some comers of the state's congressional delegation at the implication that they won't be able to get by without him, although they won't say so publicly. Some think they bent over backwards during Rostenkowski's re-election campaigns to let him take credit for projects in which he had minimal involvement.

|

There is more than a little resentment in some corners of the state's congressional delegation at the implication that they won't be able to get by without him

|

Despite protestations to the contrary from his staff, it was evident before his election defeat that Rostenkowski's influence was already on the wane because of his loss of the Ways and Means chairmanship.

He even lost a couple of public tussles with Lipinski, a Democratic representative from Chicago's Southwest Side who

has never been a particular friend of his fellow Polish-American from the Northwest Side. In one of those disputes, House members rose up to side with Lipinski on a procedural matter that embarrassed Rostenkowski, some of them sending the former chairman an implicit message that they were tired of his heavy-handed tactics of the past.

But Rostenkowski still had enough oomph, owing to loyal friends and others who feared that he'd regain his post, to help out the city one last time. In a move that was vintage Rostenkowski, he used an obscure parliamentary maneuver intended for technical clarifications of legislation to "clarify" that the Defense Department is supposed to pick up the $ 100 million cost of moving the National Guard out of O'Hare Airport to free the land for private development. The matter, however, hasn't been clarified sufficiently for the Pentagon, and the Democratic congressmen who helped Rostenkowski in his effort have lost their power in the Republican takeover.

Rep. Dick Durbin, the member of the Illinois congressional delegation who had been generally regarded as Most Likely to Succeed Rosty as the state's "go to" guy in Washington, had no illusions that he could fill Rostenkowski's shoes with his 12 years of seniority, even before the new Republican majority sidetracked his growing influence on the House Appropriations Committee.

"To have the chairmanship of the Ways and Means committee in your delegation is a once in a political lifetime opportunity," said Durbin, who was put on appropriations by Rostenkowski. "The rest of us, when the day comes, will do our best."

Mark Brown is part of the Chicago Sun-Times' investigative team that broke many of the major stories about Rostenknowski's financial affairs.

December 1994 / Illinois Issues / I 7

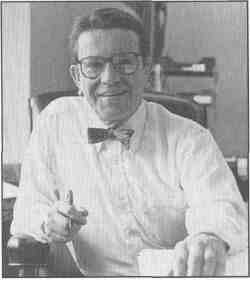

Simon bows out of '96 U.S. Senate race

U.S. Sen. Paul Simon

|

More people are relying on television/or their news. All they may get is 30 seconds of information about a bill that we've been debating for two weeks

|

Long before Paul Simon and Alan J. Dixon shared the title of U.S. senator from Illinois, they were seatmates in the state legislature.

"This was back when we were kids in our 20s," Dixon said, recalling a favorite anecdote about his former colleague. "It was

during the [Joseph] McCarthy era, and I was standing up arguing against [a] bill that would have made janitors and other people sign un-Communist oaths. It was just some silly red scare thing.

"A House page comes up to me and hands me a note written in red ink that says, 'Keep talking, you damn fool I'm gonna shoot and kill you from the balcony.' I turned to Paul Simon, who sat right next to me, showed him the note and asked him what he thought of it. And he says, 'I sure hope he's a good shot.'"

Such wit and humor, even in the face of hostility, has helped carry Simon through 40 years of politics. But it wasn't enough to push him to run for a third term in the U.S. Senate not in the current political climate that carries, he says, "a meanness in spirit."

"Without a doubt, what we saw in the November elections is the meanest campaigning I ever saw," Simon said. "I campaigned in eight states, and when I went back to the hotel rooms and turned on the television and saw the ads with everyone

calling each other crooks I don't think there's a question that this was the nastiest I've seen."

Simon's announcement last month that he won't seek re-election in 1996 is another blow to Illinois. Following the retirement of House Minority Leader Bob Michel and the defeat of powerful Rep. Dan Rostenkowski in the November election, Simon's political retirement means the state will have less seniority and clout on Capitol Hill. He was a member of the Senate Judiciary, Budget and Foreign Affairs committees.

Although he was favored to win re-election, Simon said he couldn't look forward to fund-raising for a campaign that would cost him an estimated $10 million. And he said he wants to leave public office while he still enjoys what he's doing unlike many of his colleagues.

One reason the fun has been draining from his job, Simon told Illinois Issues, is the changing nature of politicians and the public.

"You see it over and over: There are many people who just haven't done the basics in following what's going on," he said. "They're more interested in things like the O.J. Simpson trial than in the important issues that face the country.

"One of the problems is that more and more people are relying on television for their news rather than newspapers and magazines.

When that happens, all they may get is 30 seconds of information from a newscast about a bill that we've been debating on the Senate floor

for two weeks. And sometimes when you watch the report you wonder if they were attending the same session you were at."

Along with this narrowing voter attention span, Simon said, has come politicians' increasing tendency to follow polls. "That hurts the public in two ways. We don't face up to the real issues that provide answers that make sense. And it disillusions the public, who sees the

politicians as simply pandering to them." He says politicians don't need to become slaves to public opinion. "Even though they may disagree with what you're saying, people want a candidate who is candid."

That's how Congressman Dick Durbin of Springfield sees Simon. He first met him in 1966, when Simon was a state senator, Durbin was fresh

out of college, and both were campaigning for former U.S. Sen. Paul Douglas. "The thing that makes him so different is his honesty," said Durbin. "Not just his fiscal honesty although for years he's disclosed his finances in detail, even down to how much money his kids brought in from paper routes but his honesty on issues."

While campaigning for his second Senate term, Simon questioned the appropriateness of Chief Illiniwek. "There were 100 ways for Paul to duck out of that, but he refused to," said Durbin.

Before he became one, Simon helped keep an eye on elected officials. As editor- publisher of a chain of 14 weekly newspapers, including the downstate Troy Tribune, Simon investigated gambling connections among public officials in Madison County. Then-Gov. Adiai Stevenson ordered police raids that shut down several establishments, and Simon ended up testifying before the U.S. Senate's Kefauver Commission investigating organized crime.

His crusading continued even after he was elected to the Illinois legislature at age 25. When he failed to interest Springfield reporters in a story about legislative corruption in Illinois, Simon made national headlines by teaming up with a free-lance reporter to write the story himself for Harper's magazine.

Although his political career hasn't hampered his writing he has written 15 books and still pounds out a weekly column on a manual typewriter Simon may put more time into such endeavors when he leaves the U.S. Senate. One thing that's captured his thoughts lately is the future state of political affairs.

"I am concerned," he said. "It's too negative. The key word politicians should remember is trust. People may not even

agree with everything you feel, but they want to have faith in you."

Jennifer Halperin

18 / December 1994 / Illinois Issues