|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

By JENNIFER HALPERIN

It was a week before the November election, and Jorge Monies had his hands full at the Jim Edgar campaign office in Chicago's Little Village. The office answering machine was spewing a string of messages from potential volunteers, which Montes was jotting down as fast as he could. People wanted to pick up signs for their yards. They wanted leaflets to distribute. They just wanted to help.

Such interest wouldn't be a surprise in most Illinois communities. After all, the Republican governor was predicted to be re-elected by a wide margin. But Little Village, with an 85 percent Latino population, is a traditionally Democratic stronghold. Many expect voters in this West Side community to turn away from Republican candidates. Sandwiched between tacquerias and mim-mercados on bustling 26th Street, the Edgar office wasn't expected to attract much attention and support.

"There's a misconception that Hispanics all vote one way: Democratic," says Montes, who sits on the state's Prisoner Review Board and is president of the Latin American Bar Association. "But we've seen Hispanic Republican congressmen elected from Texas and Florida just as we've seen them in Democratic offices. It shows that no party can afford to take us for granted or ignore us."

Indeed, the days when Illinois' Latino population could be overlooked as a relatively small, poor and powerless minority are long gone. Their numbers are skyrocketing. They're a growing economic force. And they're mobilizing politically. As state Sen. Miguel del Valle, a Chicago Democrat, puts it:

"We're like a sleeping giant — with one eye open and the other one getting there."

Visits to Little Village and other West Side neighborhoods such as Pilsen and Humboldt Park reveal vibrant communities: Restaurants are packed at lunchtime with hungry patrons ordering arroz. con polio and fried plantains. People have covered their garage doors and businesses with bright murals in an effort to discourage gang graffiti. Festive Spanish music blares from passing cars and storefronts. This colorful surface is not unexpected. What's underneath, though, might surprise many people.

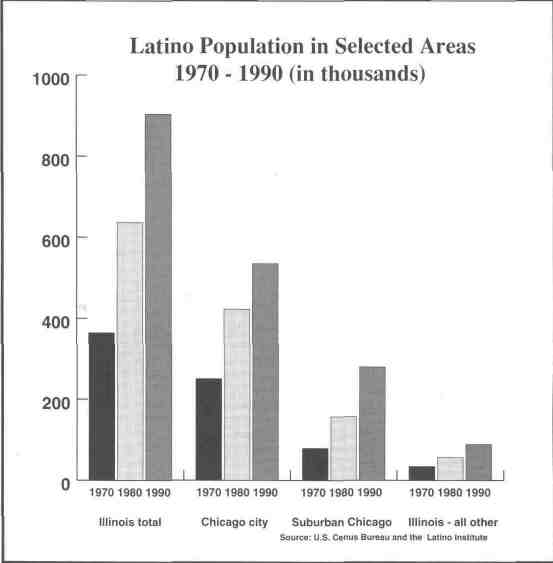

For one thing, the number of Hispanic residents is growing like crazy in Chicago and across the state. Census figures show Illinois ranks fifth in the nation in total Hispanic population. Between 1970 and 1990, the number of Latinos in Illinois ballooned to 904,400 from 364,400. More than 535,300 Latinos lived in Chicago in 1990, census figures show, while 280,000 lived in the suburbs.

And Hispanics' growing power isn't just a result of population growth, says state Sen. Jesus Garcia, a Democrat whose district includes Little Village; they're becoming a potent economic force.

The 26th Street corridor in Little Village is among the most lucrative business districts in all of Chicago, based on sales tax revenue. In fact, many Hispanic business owners have done so well they've opened second and third stores in the nearby suburbs of Cicero and Berwyn.

| Little Village has the highest concentration of Mexicans in the Midwest. A lot of goods they want from Mexico can only be gotten here |

"I think the numbers speak for themselves," says Bill Velazquez, executive director of the Little Village Chamber of Commerce. "In 1990 there were 480 stores in Little Village; now, four years later, there are 850. We had static growth in the 1980s, but since then we've about doubled the number of businesses here.

"It shocked me when I first heard how well we do compared to other business corridors in the city," he says. "But Little Village has the highest concentration of Mexicans in the Midwest. A lot of goods they want from Mexico can only be gotten here, so Mexicans from other parts of the city and region come here."

Velazquez' one lament is the business district's failure to attract tourists. "We can do better in promoting the area, because our own community supports our businesses now. The piece we're missing is outsiders."

The growth of areas such as 26th Street encourages Garcia's aide, Marcelo Gaete, who says economic success leads to

24 / December 1994 / Illinois Issues

respect, power and increasing self-sufficiency for Hispanics.

"People still see us as selling tacos from a stand," he says. "That's not who we are anymore."

Hispanics may have been underestimated on the political front as well. Sen. del Valle has first-hand experience with the way growing numbers of Hispanic voters can take an unsuspecting community by surprise. He credits his first victory — against incumbent Ed Nedza in the 1986 Democratic primary for his Senate seat — to those in power being unaware of Hispanic voting power. "It was an example of Democrats not paying attention," says del Valle, the first Hispanic elected to the Illinois Senate. "They didn't know we were out there, using Hispanic media, appealing to Hispanic voters."

And since then, political organizing efforts among Latinos have snowballed.

Danny Solis is president and executive director of the United Neighborhood Organization, a community-based group with chapters in three Hispanic neighborhoods in Chicago. He says there were 132,000 Latinos registered to vote in Chicago in 1992. A mere two years later, there were 182,000. "Maybe that's not real impressive," he says, "but we're projecting that by the end of 1996 we'll have 300,000 registered." Along with African Americans, Hispanics and other ethnic groups have the only rising populations in Chicago.

Energetic citizenship drives across metropolitan Chicago are boosting these numbers. A federal amnesty program gave 3.1 million immigrants across the country legal permanent resident status in the late 1980s. Now those legal residents are becoming eligible for citizenship, and thus eligible to vote — including 100,000 Mexicans in Chicago, says Solis.

Communities elsewhere are feeling the growth as well. There are nearly 90,000 Hispanics outside the metropolitan Chicago area, many in the Quad Cities and Rockford areas.

|

Photo by Richard Foertsch

Hispanic women's restaurant serves up cultural, intellectual dishes to Pilsen Chicago's Hispanic community is booming. And a pair of entrepreneurs in the largely Mexican Pilsen neighborhood on the city's West Side wants to make sure women get a taste of the economic growth. Carmen Velasquez and Rosario Rabiela opened La Decima Musa restaurant in 1982. Since then, it has come to be known as the heart of Pilsen's intellectual community. Its walls are lined with posters of people who have inspired society in different ways — from Galileo to Marie Curie to Anne Frank. Poetry readings, experimental theater, music and dance have become standard fare. "Carmen and I believe women should have options," says co-owner Rabiela. "When we opened, there were not many businesses in Pilsen owned by women. They said we'd never survive one year. Now, knock wood, we've been here for 13 years." Rabiela hopes the activities at Decima Musa inspire Hispanic women to make themselves heard and take a place at the cultural table. "Certainly in our community there's a stereotype of a boys' network that doesn't include women unless they want something done," says Rabiela. "So we've had our own activities: writers' workshops, theater presentations, political rallies, mesas regondas — roundtable discussion of women in today's society." Even the restaurant's name is meant to be inspirational. La Decima Musa — the 10th muse — is named after Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, a 17th- century Carmelite nun who is considered the first feminist in North America. Sor Juana was a poet and playwright who entered the convent in the late 1600s as a way to educate herself during an age when women were denied schooling. She refused to bow to church criticism over her intellectual pursuits, and her colleagues named her La Decima Musa — equating her with the nine muses of Greek mythology who oversaw learning and the creative arts. Just like La Decima Musa — who wasn't supposed to pursue intellectual feats in her male-dominated culture — Rabiela and Velasquez have stepped out of stereotyped roles in their own community three centuries later. They have inspired cultural growth among Hispanics as a whole. And they've made sure women get to enjoy the fruits of their community's increasing economic prosperity. Jennifer Halperin |

December 1994 / Illinois Issues / 25

Photo by Richard Foertsch

| As the Latino population has skyrocketed in Chicago neighborhoods like Pilsen, residents have tried to keep gang graffiti to a minimum. Brightly painted murals and signs are a common sight in these communities, often adorning storefronts and residences. |

But the numbers are really creeping up in the suburbs, says Armando Saleh, citizenship project coordinator for the Chicago office ofNALEO, the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials.

"Wheeling, Wood Dale, Melrose Park, Bensenville — there's been a lot of growth. Now we have suburban officials offer us space in City Hall for naturalization efforts, and provide police officers to do the necessary fingerprinting," says Saleh. "They recognize Latinos as a strong political power."

Some political organizers even believe this power will enable a Hispanic voting bloc to elect whomever it wants as Chicago mayor by the year 2000. In the last two years, Hispanics have doubled their representation on the Cook County Board and in the legislature, electing two senators and four representatives. Community activists say next year Hispanics will boost the number of seats they hold on the Chicago City Council to seven from four. Illinois' first Hispanic congressman, Luis Gutierrez, took office in January 1993.

This mobilization comes as Latinos grow angry about their needs being overlooked. They're tired of sending their kids to classes held in the coatrooms and closets of public schools. They're sick of keeping children holed up at home after school out of fear they'll encounter gangs.

A breaking point came recently when the Chicago School Board wanted to implement a controversial busing plan to relieve school overcrowding. A group of Hispanic parents staged a school boycott and hunger strike, attracting much media attention and eventually persuading the board to build a new school in the neighborhood instead of starting the busing program.

"My gut feeling is people will look at that as important," says Gaete. "We've been fighting overcrowding for years, but with this we got reactions from the press and politicians. It was our introduction to the larger community."

Garcia says this larger community includes areas outside Chicago. "Hispanic activists are networking with people in East Moline, Elgin, Sterling — outside of Chicagoland — and they engage local politicians."

He says even Senate President James "Pate" Philip, a conservative Republican from the suburbs, has been open to discussion of Hispanic needs. Despite comments such as "Let 'em learn English," which revealed hostility toward bilingual education programs, Philip allowed two mild bilingual proposals through the state Senate last year, and has met with Hispanics in his community to hear their concerns.

But there's much more to be done, says del Valle. Another bill related to bilingual education has languished in the Senate, and Hispanic leaders are afraid anti-immigrant sentiments may

26 / December 1994 / Illinois Issues

spur movements in Illinois to restrict social services for immigrants.

"There is a climate in this country developing, and we have to be alarmed about it," del Valle says.

At the same time, Latinos insist they are not a monolithic group with a single agenda. To those who don't know better, the Hispanic community can look like a sea of brown faces. "In reality, we're all shapes, all colors," says Gaete, 28, who was born in Chile and came to the United States when he was 9 years old. The largest group of Hispanics in the metropolitan Chicago area is Mexican (65 percent), followed by Puerto Rican (22.6 percent), according to 1990 census figures. Immigrants from Guatemala, Cuba, Ecuador, Colombia, El Salvador, Peru and Honduras each make up slivers of the Hispanic population.

These groups have converged on Chicago in large part because of the city's history as a port of entry for immigrants and the long-time presence of manufacturing jobs there. The city's lower West Side in particular, where Little Village sits, has been peopled since the 1870s by waves of Irish, German, Polish, Swedish, Lithuanian and Italian immigrants. In recent decades, Mexicans moved in to establish businesses, restaurants and social centers. Central and South Americans have followed suit.

"Every group brings something different to our society; their baggage is a lot different," says Gaete. "And not everyone who comes from one country, Mexico for example, comes from the same region or has a peasant background."

What's more, Solis foresees a philosophical change among Latino voters.

"They consider themselves immigrant ethnics rather than a racial minority," he says. "When a Mexican immigrant comes to this country, he doesn't say, 'I'm a minority and I need to be protected, so I'm entitled to handouts.' He says, 'I'm lucky to be here. I'm going to work hard and try to achieve the American dream.' Their basic attitude is that government should get out of their way."

Solis says this will mean a shift toward conservative voting patterns among Latinos, even within the Democratic Party.

Garcia agrees. "A lot of them are new voters, and they'll be independent-minded people who scrutinize particular candidates."

Which explains the potential enthusiasm among Hispanics for some conservative elements of the Republican agenda, such as anti-abortion and pro-family sentiments, as well as decreased government intrusion. Although Latinos in Chicago still vote ovewhelmingly Democratic, their partisan diversity is unmistakable. One look at Monies, sitting in the Edgar campaign headquarters among signs that read "Edgar: el nuestro amigo," brings this home.

Montes says such independence should constitute a wake-up call for the state's political parties.

"The powers that be should be taking note."

December 1994 / Illinois Issues / 27

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |