|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Catherine E. Breen, Gerald A. Danzer, Conflict threatened the Union in the early 1800s. In 1818 Illinois' northern boundary was born in an atmosphere of political compromise at the national level regarding slavery. Since Mississippi had just been admitted as a slave state in 1817, and Alabama would follow in 1819, it was necessary for Illinois to be placed firmly into the free state column. The Missouri controversy of the next few years demonstrated the issue with great clarity, resulting in Missouri's admission as a slave state. But future state boundaries were put into the scales to reach a compromise. Adjusting boundaries of new states became a way to balance interests. Boundary compromise in 1818, however, produced later controversies for Illinoisans. Boundaries are like fences, and "good fences make good neighbors." As a text for analysis in social studies classrooms, this saying can lead in several directions. It makes sense to agree upon limits to reinforce boundaries with fences, and respect neighboring fields by keeping animals fenced in and away from the fields and gardens of others. In modern life, good fences keep your dog at home, out of your neighbor's flower bed, and away from the patio party down the block. But fences or boundaries also define an area, collecting space into a definable unit. The geographic concept of location and the historical sense of place both come into play. For example, think of Illinois as an entity whose extent was set by Congress when it defined the boundaries of the state. Boundaries also create a distinctive space within their confines, creating some interesting dynamics that, over time, will create a sense of place. Thus, after its boundaries were established in 1818, Illinois acquired not only its physical appearance but the ingredients to develop a unique character.

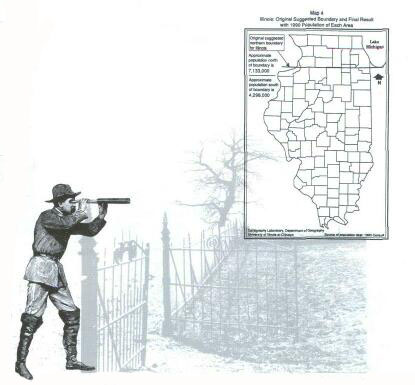

Here, inside the boundaries, were well-springs of internal conflict. When the Illinois territorial legislature decided to request statehood in 1817, the boundaries of the future state were easy to envision. In the south and east they were already set by the states of Indiana and Kentucky; to the west the Mississippi River had always been considered a natural boundary. The only question was the northern dividing line, and there, history offered several options. The first option dated back to the Northwest Ordinance, which prescribed an east-west line touching the southern tip of Lake Michigan as the northern boundary of the third state (Illinois) and the southern boundary of the fifth state (Wisconsin) to be created from the Northwest Territory. The latter provision provided the basis for Wisconsin's later argument for a southern extension of its boundary. Map 1 shows the boundaries as set by the Ordinance of 1787. The law permitted these boundaries to be altered by "common consent," opening the door to numerous adjustments over the years. See Map 2. These changes were rooted in geographic misunderstandings, local politics, and national concerns. The second option in setting the Illinois boundary was to use the northern line of either Ohio or Indiana as an alternative limit for Illinois. Note how the Northwest Ordinance intended the northern boundaries of all three states to be on the same parallel. But a geographic misunderstanding led to several adjustments. In 1787 the map used by Congress mistakenly showed the southern tip of Lake Michigan to be several miles further north. Thus when Ohio became a state in 1803 its northern boundary was set too far north. The port of Toledo on Lake Erie thus became part of Ohio rather than Michigan. When the truth was discovered, Michigan was outraged. The dispute was finally settled in 1837 with Ohio keeping the mistaken lands and Michigan receiving the upper peninsula as compensation. When Indiana applied for statehood it could use either the original northern bound- 2 ary for the second state of the Old Northwest, or it could extend Ohio's mistaken line westward. The final decision, in 1816, was to push the boundary further north, giving Indiana an additional northern strip so that it might develop harbors on Lake Michigan. Congress agreed that this revised northern limit should be ten miles north of the original boundary. Thus when the time came to draw the Illinois line, there were two precedents already set, one about six miles and the other ten miles north of the Ordinance line. The third option available in 1818 was to disregard all of the previous lines and to create a new one based on current concerns. When the Illinois Territorial legislature, meeting in Kaskaskia, resolved to send a memorial to Congress requesting statehood, its members knew that the required population of 60,000 had not yet been obtained. At best, the region could claim 36,000 souls, but an element of haste was induced by the fear that when Missouri, a slave territory across the river, would seek statehood, a national political crisis might put everything on hold. Thus the official memorial to Congress requesting statehood was deliberately vague about such things as population and boundaries. Nathaniel Pope, the delegate to Congress from the Illinois Territory, steered the enabling act through Congress. At first the congressional committee suggested that the northern boundary of the new state agree with the Indiana line, but Pope boldly suggested that the parallel of 42°30" be used instead. This would push the border about 31 miles north of the provision in the Northwest OrdinanceŚway beyond Indiana's northern extremity. The reason for Pope's bold move was "too obvious" for him to spell out in detail, although he did speak pointedly about the necessity of connecting the new state with the northern interests of New York and New England through a port at Chicago. He also suggested that a canal connecting Lake Michigan with the Illinois River would do more than facilitate commerce, swinging Illinois into the political orbit of the northern states, thus "affording additional security to the perpetuity of the Union." The spirit of compromise that led to the addition of 14 counties and 8,000 square miles to Illinois, however, also set up the internal dynamics of state politics. The development of Chicago eventually placed more than half of the citizens in the state in the northern addition. The balance of political power stood precariously between the rural "downstate" interests and the urban center in the far northeastern reach of the state. Much of the political conflict in Illinois since the 1850s can be interpreted in terms of this tension. After 1950 a third factor was added to the state's political dynamic when the growth of suburbs in the metropolitan area created another political block. Thus today's patterns of conflict and compromise that animate the story of state government in Illinois are often analyzed in terms of political blocks representing downstate, suburban, and Chicago interests. Such is the wheel of political activity as it moves from conflict to compromise to new conflicts and new compromises, on and on, hopefully attracting our best ideas and our highest motives. But the whole picture is given greater perspective when the origins of this political dynamic are placed in the historical context of 1818, when the need for compromise on the national level was so acute.

Click Here for Curriculum Materials

3

|

|

|