|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By SCOTT BURNHAM

Mired at the back of the pack

Despite generous subsidies, Illinois racing suffers from

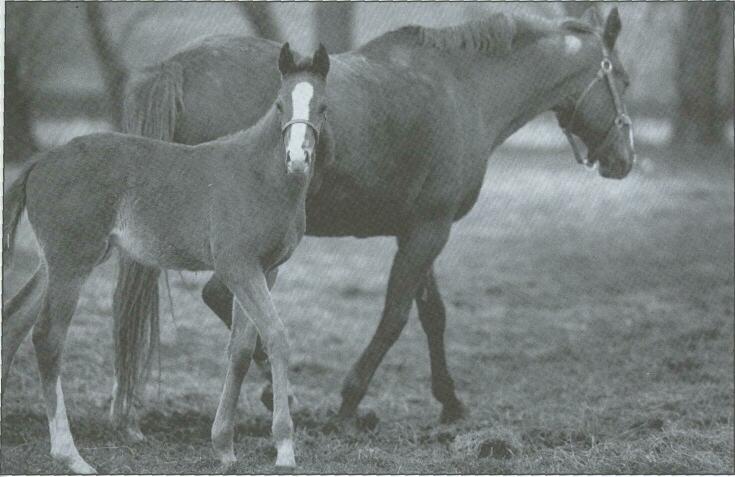

uncompetitive horses and competition from casinos. Now a task force tries to save a billion-dollar industry When the 3-year-olds come spinning out of the turn in this year's Kentucky Derby, an Illinois horse won't be among them. Larry The Legend, a small but gutsy bay colt born and bred in the Land of Lincoln, is eligible but is injured. He would have been the first Illinois horse in six years to make a run for the roses. An underdog, Larry won the Santa Anita Derby April 8 in a photo finish. But much to the chagrin of the state's racing indusfty, runners like Larry have been few and far between. In 120 runnings of the Derby, only one Illinois horse, Dust Commander, who ran in 1970, has been a first-place finisher. Despite pumping in more than $20 million annually to help Illinois horse breeders and owners — one of the most lucrative government-sponsored programs for horsemen in the nation — the state has fallen short of producing quality thoroughbreds that can compete with those from Kentucky, California, Florida and New York. "They just don't stack up," says John McEvoy, associate editor of the Illinois Racing Form. "Illinois horse racing may be established and competitive here, but very few horses can compete outside the state." Concerns about the quality of Illinois thoroughbreds reflect a larger debate about the stature of the state's horse racing industry. The size of the purse — or prize money — drives that industry, and since the mid-1980s purses have been declining as off-track betting parlors and floating casinos lure more and more weekend bettors from the tracks. Illinois' purse money doesn't compare favorably with other states. The average daily purse at Arlington International Racecourse is $188,000, compared to $372,000 at Saratoga Racecourse. So, in early April, Gov. Jim Edgar's newly appointed task force issued a set of recommendations aimed at making racing more competitive with other forms of gambling and putting Illinois' horses in the same league with those from other states. Edgar's interest in Illinois racehorses transcends his enthusiasm for the sport. What's at stake are 37,000 industry jobs and a whopping $1.3 billion wagered at state tracks and off-track betting parlors annually. Nearly $80 million is poured into the state's bank account and local economies each year.

The task force called for expanded simulcast wagering on races from across the country and around the world and for additional off-track betting parlors. Such proposals are aimed at increasing the number of bettors and, ultimately, the size of the purses. But the task force report also calls for an equitable distribution of betting commissions between track operators and horsemen. Also of interest to horsemen, the state's breeding program would be revised to increase financial incentives for Illinois-bred horses that race against horses from other states, while decreasing awards for those that run in races restricted to Illinois-bred horses. State tracks currently are required to run at least two restricted races a day. In recent years, the program has worked against enhancing the stock by shielding Illinois horsemen from the necessity to compete against better runners from out of state. In short, the incentives have created an inclusive, lower-class circuit, where state-bred horses are competing more with one another. Restricted races make it easier for Illinois horses to win and provide a kind of "protection," says David Nobbe, general manager of Horizon Farms in Barrington Hills, which is just 40 minutes from downtown Chicago and breeds more than 75 thoroughbreds a year. Illinois ranks third — behind California and New York — among incentive program payments nationwide, doling out $16.8 million in 1992. But the state ranks eighth in bonuses paid to breeders and 14th in money to owners. And most of the money goes toward purses for races that are restricted to Illinois-bred horses: Illinois pays out $15 million, second only to New York. Even in the restricted races, though, that figure is inflated, because Illinois counts the purse money along with the bonuses. "States always want their incentive programs to look the best," says Pat Whitworth, secretary/treasurer of the Illinois Thoroughbred Breeders and Owners Foundation. At the same time, though Illinois horses are winning an increasing percentage of races, more of those races are restricted. In 16/May 1995/Illinois Issues 1982, 33 percent of all state races were won by Illinois breds. By 1993, that number had grown to 43 percent. And, as the industry came to rely on restricted races, the quality of horses diminished. Because the restricted races are a surer bet, the argument goes, fewer horsemen are willing to stake their dollars on more competitive — and more expensive — stock. "The industry is being watered down," says Christine Janks, president of the Chicago division of the Horsemen's Benevolent and Protective Association, an organization comprised of owners and trainers. "To put more money into an industry that does not increase its productivity is like doing business in a vacuum — no business could possibly survive." Yet, the Horse Racing Act of 1975 was intended to encourage the breeding of "high quality" Illinois thoroughbreds and to help the state reap the agricultural and commercial benefits. The statute set up the Illinois Breeders Fund Program, which provides subsidies and incentives for Illinois-bred horses. The program gives money to breeders, owners and stallion owners through purse supplements and awards. The purse supplements and owners and stallion awards are drawn from 8.5 percent of all money raised by the Illinois privilege tax — about 2 percent of the handle, or money bet at all thoroughbred races. Breeder awards are paid by the tracks. In open company races, 11.5 percent of the winner's share goes to the Illinois winner. In restricted races, that percentage is divided among the top four finishers. Smaller purses attract fewer outside horses, however, so tracks slate fewer open races. "You want to keep the horse where the competition is easiest so you'll have a better chance of winning races," says Nobbe, whose 600-acre farm employs 35 people from farm hands to college graduates. "The laws protect Illinois breeders, but the issue is whether the laws encourage quality in breeding or mediocrity," says Lorna Propes, a member of the Illinois Racing Board. "There are ways to make Illinois horses more competitive with other states, but it may mean that some breeders may not survive." In fact, some in the industry, particularly Arlington International Racecourse owner Dick Duchossois, have called for opening up the restricted races to enhance competition and drive up purse money. "It's like welfare," says Arlington spokesman Paul O'Connor. "You're giving away incentives that don't work. It creates a dependency and a marketplace for bad horses." O'Connor says that Illinois should do away with restricted races and model its program after Kentucky's,

Photo by Tom Holoubek

May 1995/Illinois Issues/17

rewarding "on the basis of competitive standard." That may draw bettors back to the tracks, but, critics say, it wouldn't bode well for those Illinois breeders whose horses wouldn't stand a chance in open competition. "Breeders will go out of business or move where they can make money," Nobbe says. "And how does that benefit Illinois?" says Jim Reynolds of the state's agriculture department and a task force member. "The breeding program creates jobs and breeders buy Illinois products and commodities. It's a way to keep the money in Illinois and recirculate it." "With the restricted races, a lot of big racing stables will buy Illinois breds to flesh out their stables because they know they can run for restricted purses and make money," says Joan Colby, editor of Illinois Racing News. "Without restricted races, the race tracks wouldn't be able to fill a full card and probably wouldn't survive." O'Connor offers a simple solution to that problem: "Don't race." Duchossois and other track owners argue that the vitality of Illinois racing is threatened by the state's regulation of the sport. But they appear ready to cut horsemen in on any deal to overhaul those regulations. Track owners, for instance, take in a disproportionate share of the handle at off-track betting parlors. OTBs began luring bettors from live racing in the 1980s and, because 65 percent of all money bet on horse racing is wagered off-track, the purse return for horsemen in most cases is significantly less than it would be if the money were bet at the track. The consequence is that Illinois owners and trainers are leaving for greener pastures out of state. In addition, when the state reduced the privilege tax on betting, less money went to the bettor and less to the breeders. As the profits declined, fewer horses were born and bred in the state. In 1983, 1,912 newborn horses were registered in Illinois, compared with 1,289 last year. "That kept the breeding program at a standstill," says Pat Whitworth of the Illinois Thoroughbred Breeders and Owners Foundation and a task force member. "So when the other states have been growing, we've lagged behind." Most breeders believe that higher purse money will trickle down and lead to better horses and bring more people out to the tracks. But Christine Janks, who owns the Emerald Ridge Farm in Mundelein, believes higher purses are not enough. She thinks of herself as a "typical" breeder, owning about 40 to 50 horses and breeding about 10 mares a year. The best way to encourage quality breeding, she says, is to increase owner awards for open races substantially, perhaps as much as 50 percent of the purse for those who win in open competition. The result will be that cheaper horses get little or nothing, while better horses will get more. Some small breeders may suffer before they begin earning more money. But Janks believes breeders must "bite the bullet" and invest more in better horses to compete in open races. "No one will ever say, 'I invested $5,000 and I can win all these races and make $40,000. And now I'll invest $10,000 and do it again,'" Janks says. "What they'll say is, 'I'll get two horses from $5,000 because I know I don't have to spend that kind of money to win these races. I can do it with a cheap horse.'" Improvement won't happen by itself, she says. "The reward must be put out so they know if they buy or breed a quality horse, they'll be rewarded for it." Nevertheless, she believes restricted races will still be needed to help the small breeder make a certain level of money, because "that's the point of the whole program." In fact, the days of the commercial breeder, one who speculates to buy and sell for profit, are probably gone. These days, most breeders are animal lovers who own a few horses and decide to breed at the end of their racing careers, Nobbe says. "For a small investment, you can have a horse racing for a fair amount of money," Nobbe says. "You won't be winning against Kentucky horses, but you wouldn't be running against them." "Whatever happens won't happen overnight; you can't legislate better horses," says Whitworth of the Thoroughbred Breeders and Owners Foundation. "And you can't wish for them or pray for them. I know because I've done all three." Ron DiCicilia, who employs 40 people at his Crown's Way farm in suburban Hampshire, says Illinois should be more concerned with the economic threat of riverboats and less preoccupied with becoming No. 1 in racing. "We'll never be the best in the country," said DiCicilia, who is satisfied with the current breeding program, but would like to see purses increased. "We can be the jewel of the Midwest and not worry about the rest of them." Even though Larry The Legend won't be at the starting gate at Churchill Downs on May 6, his career isn't over. Illinois legislators should be mindful that Larry's original owner, Photini Jaffe, a well-known breeder, declared bankruptcy and was forced to unload Larry last year for $2,500. * Scott Burnham is a reporter for The Times in Lansing, Ill.

Photo by Tom Holoubek 18/May 1995/Illinois Issues

May 1995/Illinois Issues/19

|

|

|