|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By DAVID MOBERG

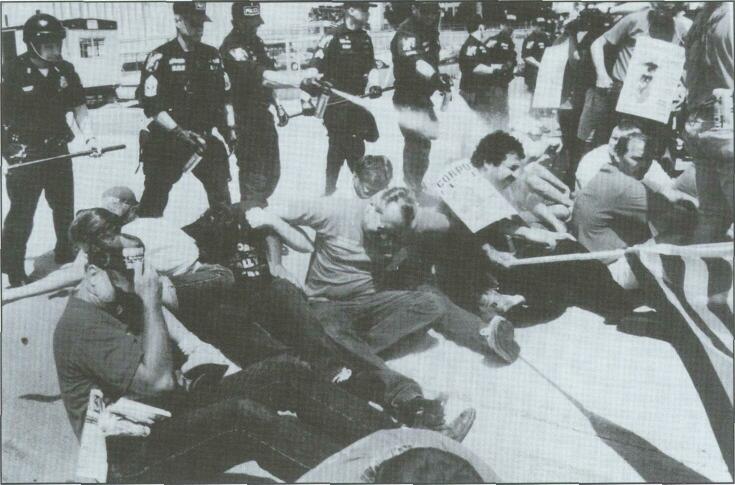

©1994 Jim West/Impact Visuals, courtesy of United Paperworkers Int'l Union Local 7837

Fraying of the union label

Democratic Party allies have lost clout, Decatur is a war zone,

labor leaders fight over political strategy. One long-time labor observer sees the movement's salvation in an old-fashioned idea: solidarity 20/May 1995/Illinois Issues At left, Decatur police spray pepper gas on A.E. Staley Manufacturing Co. workers in June 1994. The demonstration was held to commemorate the first anniversary of the lockout of union employees. Two omens of a difficult future loomed before Illinois labor unions at the start of this year. First, in Decatur, Ill., nearly 4,000 workers at the factories of three big multinational companies — American-owned Caterpillar, British-owned Staley & Co., and Japanese-owned Bridgestone/Firestone — were either locked out or on strike in prolonged and tumultuous conflicts stretching back nearly four years. It was, workers said, a "war zone," in which the heaviest tactical firepower from both sides of the labor-management divide had resulted in stalemates. To compound their woes, for the first time since 1960 Republicans controlled both houses of the General Assembly and the governor's office. The significance of this development for labor was clear soon enough: The first act of the new legislature was to repeal the 88-year-old "scaffolding act," which permitted injured workers to sue responsible parties other than their employers for damages. It was simply the first of a torrent of proposed laws that would, for example, restrict workers compensation, deny teachers the right to strike, or remove public worker unions' right to negotiate wages and working conditions. Labor's new political plight reflected not simply Republican ascendancy but also the atrophy of its independent, grass-roots political organizing during decades of over-reliance on old-style "machine" Democrats. The combined political and economic challenge is leading many labor leaders to call for dramatic changes in the way unions fight for workers' interests. Progressive unions want a more concerted effort at grass-roots labor and political organizing, more emphasis on labor solidarity and on labor-community coalitions, and a more issue-oriented approach to politics. The battles in Decatur, which have heightened the feeling of a need for change, also are prime examples of this new approach. The three unions most immediately involved have linked up with other unions from the area and across the country and have formed alliances with liberal religious and community representatives. They have fought back against not only their employers but also their employers' financial supporters, customers and corporate allies, including the Decatur-based national corporate heavyweight, Archer Daniels Midland. They have made the Decatur strikes and lockout a battle of "our solidarity versus theirs," challenging workers to recognize a common interest in resisting the demands of big corporations. They have taken their battle to the arenas of public opinion and politics, from pressuring elected officials to running campaigns for local offices. They see themselves as fighting not only for acceptable terms for their contract but for greater control over their lives. "Our fight is not just for us," argues Dave Watts, the tenacious president of the Staley workers union. "It's a fight for our kids and future generations, and how they're going to be treated." "There's no question there's a real crisis for workers in this state," argues Joe Costigan, political and legislative director for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers union and an initiator of a new labor-community coalition — Save Our Security — that will fight efforts to weaken Social Security, Medicare and other federal and state programs that protect workers' security. "Workers in Decatur and Peoria [another major Caterpillar strike site] are prime examples of long-term struggles critical to Illinois. We can't rely on our past glory. We have to fight with new tools for new agendas, programs and ideas. We can't rely on our institutional history and strength. We can't organize in the same old way." There's a common thread to the new agenda, but it's as old as the labor movement: Workers and their unions — whether they're industrial, service, or public workers — must support each other in a common fight against the power of business. That theme is certainly part of the Illinois labor legacy, from the Pullman strike to CIO organizing of the steel and meatpacking industries. Yet as University of Chicago political scientist J. David Greenstone observed a quarter century ago, the Chicago — and by extension, Illinois — labor movement has been deeply shaped by its close ties to the Democratic Machine. Labor relied heavily on individualized bargains with political officials — including an occasional Republican like former Gov. James Thompson. Compared to many other states, mainstream Illinois organized labor was even less oriented toward broad liberal legislative goals and building a grassroots political movement. Now the Machine may be nearly dead, but its legacy continues in the way Illinois labor approaches both politics and bread-and-butter union goals.

The new progressives argue that the old ways can't work in an era when business is more aggressive. Republicans are more ideologically hostile, and the old base of Democratic Party power and organization has vanished. "Our relationships [with both politicians and employers] have to be based on power, not who you play cards with," argues Tom Balanoff, the new president of the 23,000-member Local 73 of the Service Employees International Union. "For years now too many labor leaders have fought against any class analysis. Now things have gotten so bad that we have to take it to the corporations at a higher level. We can't go running around putting out fires." Balanoff believes that unions must see themselves as the heart of a broad movement representing all working people, unionized or not, and must be prepared to tackle corporations, not simply one by one as employers, but as part of a dominant, cohesive business class that is typically hostile or indifferent to workers' interests. Balanoff's message may find fertile ground as the makeup

May 1995/Illinois Issues/21

and leadership of the Illinois labor movement change. High-wage jobs in liberal industrial unions have declined, and low-paid service work has grown over the past decade, but there are new efforts by unions such as SEIU and the Teamsters to organize that sector (including 4,000 recently organized home care workers). While newly organized public employees have helped keep labor's ranks fairly stable over the past decade — around 1.1 million in 1993, labor's share of the workforce has slipped — to about 21 percent in Illinois, compared with 16 percent nationally. That means that AFSCME, the liberal state, county and municipal employee union, continues to gain relative importance. Internal changes within unions — such as SEIU and the Teamsters, where reformer Gerald Zero recently was elected secretary-treasurer of Chicago's 13,000-member Teamsters Local 705 — have also given new liberal counterbalance to the traditionally conservative and politically influential building trades. Crises such as the conflicts in Decatur also create within the labor movement a new sense of need to join together to fight business abuse of workers. These conflicts demonstrate that even cooperation with management is no protection against an employer offensive. In all three cases, the unions — United Auto Workers at Cat, United Paperworkers (formerly Allied Industrial Workers) at Staley and United Rubber Workers at Bridgestone/ Firestone — had for many years participated in cooperative programs with management that boosted productivity, quality and profits while jobs were cut. Yet when contracts came up for renewal, the companies all posed dramatic demands for concessions, such as deeper cuts in employment, more subcontracting of work, work schedules that would disrupt families and strain workers' health, pay or benefit cuts for many workers, and diminished employee rights on the job. Caterpillar and Bridgestone/Firestone both rejected "pattern" contracts previously negotiated between the unions and those companies' major competitors, which all unionized companies within an industry typically accepted with few changes in the past. In all three cases management has also taken very hard-line positions backed up by the threat — put into practice at Bridgestone/Firestone — of permanently replacing anyone who would strike. The unions, especially at Staley, but less so at Bridgestone/Firestone, have fought back with imagination. They have "worked to rule" (doing only what was required of them) while inside the plant, attacked financial and business allies of the companies, boycotted products or forced customers to end contracts (Miller Brewing stopped buying Staley corn syrup, and now the union is pressuring Coke and Pepsi), and spread their story around the country. Through regular meetings and communications, as well as symbols like their defiant red shirts, workers have created a strong sense of solidarity within each union and among the unions. Workers on strike or lockout have rallied to support other struggles — such as the AFSCME (public worker) battle against the closing of a mental health center — and to organize political campaigns for municipal elections (winning two of three contests they entered). As a result, the conflicts in Decatur have generated remarkable expressions of broader solidarity; thousands of workers from around the Midwest marching through the city streets, rallies in Chicago and other cities, outpourings of money to "adopt a family" of locked-out workers, and sit-ins — once subjected to a police "pepper gas" attack — that have often involved religious leaders. Late last year the state AFL-CIO helped with fund-raising and a rally, though during the first years of the struggle it did not come to Staley workers' aid: Their union had not paid its state federation dues. Recently, under some pressure, AFL-CIO president Lane Kirkland and national union leaders have also trekked to Decatur. However, some of these leaders had also insisted that Staley workers break off ties with independent labor strategist Ray Rogers, who along with another controversial, militant consultant, former UAW leader Jerry Tucker, had shaped much of the local's strategy. The unions that had all along been most active in support of the Decatur workers tended as well to be those who want a new political strategy — rebuild a new grass-roots, liberal Democratic Party and build coalitions with religious, community and consumer groups. For example, liberal unions had worked with former Democratic Party Chairman Vince Demuzio — with 22/May 1995/Illinois Issues support from then-Chicago Mayor Harold Washington — to give labor a bigger role in politics. Unions were asked to advise on policy through a new Democratic Labor Council and to replenish the depleted grass-roots precinct organization base of the state party. But Chicago Machine Democrats and the AFL-CIO mainstream ousted Demuzio and cut short the labor-based party building strategy. Many of the liberal unions had also been most involved in community and consumer coalitions, such as Illinois Public Action Council, one of the state's leading liberal lobby forces. But the state AFL-CIO, which has frequently allied with electric utility companies under the influence of the powerful International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, voted last year to urge all unions not to work with Public Action and other consumer opponents of utility rate hikes. It was a triumph of the old, narrow labor politics over the new agenda of labor as the champion of broad working-class concerns. Despite these continuing conflicts within labor, progressive union leaders think they see some "awakening" on the part of their more conservative brethren, "The loss of [former House Speaker] Michael Madigan's clout has sent these guys reeling," observes Public Action Associate Director John Cameron. But unlike Indiana, where the state AFL-CIO helped mobilize 25,000 workers against anti-labor legislation this spring, the Illinois AFL-CIO had only a few dozen people — including many lawyers — at their protest against repeal of the scaffolding act. "Their whole operation has atrophied so much, partly by their relying on their relation with Madigan to kill everything they oppose, and by their lack of any mobilizing agenda," Cameron contended. The state AFL-CIO and the moderate-to-conservative wing of labor "realize they have to do something different," one liberal leader argued, "but they don't have very many ideas about how to do it. But to the extent that people come with ideas, they've been pretty responsive." For example, the state AFL-CIO is supporting — though not paying for — an effort to organize grass-roots coalitions in key legislators' districts. The strategy resembles Demuzio's never-implemented plan. "Had that happened we'd be better off politically than we are today," argues retired Machinist union Political Director Charlie Williams, who was the first head of the Democratic Labor Council. Likewise, he believes it was a "terrible mistake" for labor to reject Public Action. "Labor is not big enough to do anything by itself," he said, "but if labor combines with Illinois Public Action, they can do a lot more." AFL-CIO President Don Johnson continues to describe Public Action as a group that has "worked against the interest of workers," even though they've been leading champions of health care reform, progressive taxation, environmental protection and many labor-backed bills. Though he acknowledges that Republican control of the legislature has brought "significant change" and worrisome threats, he says of the Republicans, "I've never felt like we were ever enemies, but their agenda and mine weren't walking down the same path." Despite his endorsement of the grass-roots campaign in key legislative districts, he also hopes to cultivate better relations with Republicans. "We have some relationships with a few Republicans that we've developed over the years," he said. "We're trying to improve those. We're looking at some of the new Republicans and trying to get to know them." While any lobbyist might cultivate all available connections, Johnson's approach also reflects the tug within the mainstream of labor between the old and new strategies. At the campaign office of the Staley workers in Decatur, there is no such conflict. There, on a typical evening, workers were busy cultivating ties with unions across the country and in Europe, planning a campaign against tax breaks Staley, Cat, Bridgestone and other big employers had received from the state and local government, coordinating municipal election efforts (which resulted in victories for two of the three labor-backed candidates to city council, including the mayor), and describing how they persuaded other unions such as the Teamsters (but not some building trades locals) not to cross their picket line. Though they were happy that their delegation to the winter AFL-CIO meeting in Bal Harbour, Fla., had brought new national labor support, they were deeply disappointed to read that their state federation of labor had "wined and dined" Republican politicians at that same meeting, while they had to work to get a hearing. To them it was like fraternizing with the enemy. "This is war," said Mike Griffin, one of the most active locked-out workers, "and not one that we picked either." "What's happening in Decatur is a microcosm of what the labor movement as a whole has to take on as we move into the 21st century," argued AFSCME Downstate Regional Director Buddy Maupin, a leading supporter of the embattled industrial workers in his hometown. "It's an exciting place to be. It's heartening to see people realize solidarity is our only defense. But when it's all over, I want to look back at this when I'm on my rocking chair as one of the finest moments the labor movement ever had, and it prevailed. It was a moment when confronted by the naked greed of big corporations who tried to become wealthier, common, ordinary people came together and fought against it." If Maupin's rocking-chair memories prove correct, the Decatur battles may also mark a turn of Illinois labor toward a new ethos of working-class solidarity, both in their relations with management and in political action. With the Chicago Machine in continuing decline and the state Democratic Party in disarray, the opportunities for labor to steer the Democrats in new directions are better than ever. Yet the more militant, progressive elements within the labor movement will have to overcome resistance not only from many unions that are unwilling to chart a new course, but also from the mainstream of the Democratic Party, downstate and in Chicago. At the moment they can pose a constructive challenge but probably not prevail in redefining both the Democrats and labor in Illinois, even though the new militants offer the best hope for both labor and political revitalization. Old habits will not disappear overnight, but the crises that have compelled rethinking labor's strategy are not likely to disappear soon either. * David Moberg, senior editor at In These Times, writes widely on labor and economic issues. His articles on central Illinois labor conflicts have appeared in The New Republic, The New York Times and the Chicago Tribune.

May 1995/Illinois Issues/23

|

|

|