|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By ELIZABETH BETTENDORF

Land lovers

A growing cadre of preservationists have found allies

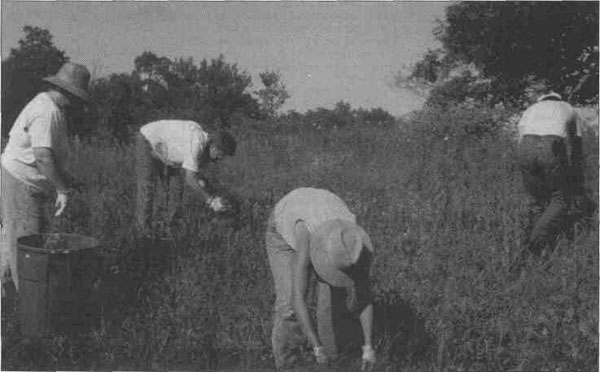

Photo by Carol Morton Schmidt One of approximately 34 densely wooded islands that once breached the quilt-flat expanse of McLean County, Funk's Grove is the largest prairie-grove remnant in central Illinois. The members of the Funk's Grove Cemetery Association spend their weekends in an effort to preserve the historic tract. Eric Funk sits in the hushed, cool interior of the old church, the gaze of his ancestors' portraits fixed on the walnut pews, kerosene lamps and wood-burning stove that have survived here for more than a century. He is a quiet, thinking man who warms his hands in the pockets of his suede jacket as he recalls a time long ago that still makes his face crease into a smile. Once, in the winter when he was a boy, he walked in the freshly fallen snow past the clapboard church with its green shutters the color of the cathedral trees that shroud the grove in the warm weather. Funk had brought his dog and the two crunched along in silence, their path illuminated by a swath of moonlight. "It was beautiful," he said. "Just me and nature and my dog." It is precisely this sort of experience that Funk and the members of the Funk's Grove Cemetery Association hope to preserve for his children and grandchildren, as well as the steady trickle of curious travelers who venture off Interstate 55 near Bloomington each year to visit Funk's Grove in McLean County. Eric Funk, the great-great grandson of Isaac Funk, whose portrait as a stern, silver-haired old man in his black Sunday coat still hangs in the back of the Funk's Grove church, is an example of an emerging breed of citizen who cares deeply, 10/July 1995/Illmois Issues often passionately about the land. Funk is also an example of someone who once feared restrictions on the family's homestead. Now he, as well as a growing number of other Illinoisans and property owners, is learning to work with experts — both private conservation groups and government agencies — to find ways to preserve the natural landscape for future generations. "As long as I am alive, I want to instill the idea of preservation, conservation and good husbandry," says Funk. "We're only here to pass the land along in better condition than we received it. We're only caretakers. We can't take it with us." One of approximately 34 densely wooded islands that once breached the quilt-flat expanse of McLean County, Funk's Grove is the largest prairie-grove remnant in central Illinois. The land is rare because it connects a lushly wooded Illinois nature preserve to the north and a restored savanna, woodland and prairie owned by the Illinois Department of Conservation to the south. Though much of the grove is a U.S. Department of the Interior natural landmark, the entire site is not fully protected. When the seven-member Funk's Grove Cemetery Association, still made up of old local families, wanted to acquire Sugar Grove, a 246-acre boot-shaped tract of land within Funk's Grove, they approached the Illinois chapter of The Nature Conservancy for financial backing. Though the conservation department had been negotiating to buy the land, the former owners were asking slightly more than fair market value for the parcel, causing the state to back off. So, in 1993 the Illinois chapter of The Nature Conservancy floated the association a $321,000 loan to help cover the price of the property. Originally created to provide for the care and upkeep of the elegant old church and tiny graveyard, the Cemetery Association has since enlarged its duties to include the preservation of the historic grove. The association repaid the loan in January, and an informal ceremony was held this spring at Sugar Grove, which will be coaxed back to a savanna and woodland system. Though the Funk's Grove families have closely guarded the integrity of their land for more than a century and a half, until recently they remained wary of state government and conservation experts. But their trust grew over the last few years, Funk says, after members of the association attended meetings with representatives of The Nature Conservancy (a private organization), the publicly funded Illinois Nature Preserves Commission and the state's Department of Conservation. Voluntary initiatives proving effective In Illinois, less than 1 percent of the original landscape remains in its natural state and more than 50 percent of the state's threatened and endangered plants and animals are found on private property. Because public dollars for land acquisition and preservation efforts are drying up, voluntary conservation initiatives like the one at Funk's Grove are proving an effective means of preserving the character of everything from blufflands to prairie to wetlands. According to a 1994 survey by the Land Trust Alliance based in Washington, D.C., there are 27 land trusts in Illinois. Often not-for-profit and regional-or community-based in focus, the trusts — also known as conservancies, foundations or societies — have helped protect 44,230 acres, which have been donated or purchased to create protective easements or nature preserves. The strongest legal protection for land in Illinois is dedication as a nature preserve. The mission of the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission — established in 1963 and funded by the Illinois Department of Conservation — is to help landowners set aside natural areas and species habitats. The commission has located 610 high-quality, undisturbed natural areas across Illinois. Half of these are unprotected. Every year, about a dozen new nature preserves are dedicated in the state and the transaction is recorded in the local county courthouse. Saving a rare black-soil prairie An example of an unexpected find is the prairie owned by Joseph Bystricky. In 1941, Bystricky's father bought land five miles north of Woodstock from a family that had owned it since the mid-1800s. The deal included a 17-acre swath of rare and beautiful black-soil prairie that still sprawls below Bystricky's commercial orchard operation. The land, which has since been dedicated as an Illinois nature preserve, has never been cultivated. For years, Bystricky, now 78, had burned and restored it on the advice of the previous owners. Yet, worried about the future, he wanted to do more. 'The prairie is my pride and joy," he says. "I just wanted things to stay the way they were. I'm old enough to appreciate what we had and what we're messing up. Development hasn't touched me. The prairie is out of reach to developers, and thank God for that." Gillian Moreland, a field representative for the Illinois chapter of The Nature Conservancy, who first visited Bystricky's undiscovered prairie in 1987, admits she was completely awed by what she encountered: "I found myself in the most incredible place," Moreland recalls. "Up here in McHenry County, where we're suffering the growth of Chicago, the whole countryside could be gone in no time flat. But here was this area — the most gorgeous area — with rare flowers that one can't even find in a field book." In fact, Bystricky's prairie is believed to be the only one of its kind in McHenry County, and one of the few left in the state. A black-soil prairie is particularly rare in an agriculturally rich state such as Illinois because most were long ago cultivated for farming. "I think Joe Bystricky is a really rare person," Moreland says. "He was really protective of the site. He was so excited when he found out he had something special and rare. These little remnants of prairie can teach us so much." At Funk's Grove to the south, all 200 acres of the conservation department property and 24 acres of the Sugar Grove tract have been dedicated as an Illinois nature preserve buffer, a designation that offers the same legal protection as a nature preserve, says Mary Kay Solecki, a central Illinois field representative for the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission. But the property enjoys even more protection because 30 acres of adjoining forest once owned by Thaddeus Stubblefield — who died in the 1940s but who requested special protection for the woodland — were also dedicated as a nature preserve in 1993. "It's basically an alliance of partners that may at one time have seemed unlikely," says Solecki, adding that all three properties were dedicated in tandem with "everybody holding hands and jumping in at the same time. We realized that it was the best way for everyone involved to build and maintain trust." The joint restoration of the Sugar Grove tract in Funk's Grove and

July 1995/Illinois Issues/11

the nearby conservation department's property is a historically significant effort. By working together, The Nature Conservancy, along with state government, private landowners and a vast network of volunteers restored the land to a condition found prior to European settlement. In the process, they created "one big preserve rather than an isolated piece of property," says Don Schmidt, a horticulturist at Illinois State University, who leads the restoration activities at Funk's Grove and helps coordinate the efforts of The Nature Conservancy's volunteer network in the Funk's Grove area. "We know that somewhere around here forest and prairie met each other and created savannas [a grassland containing large scattered trees]." But sometimes property owners are just as eager to protect smaller parcels of land. In McHenry County, Perle and Carl Olsson of unincorporated Ringwood also longed to protect their land. But their property — 2 1/2 acres of restored prairie that burgeons through the seasons with trillium, butterfly weed, yellow buttercups, prairie smoke, yellow star grass, blue-eyed grass and prairie violets — was too small to interest large conservation groups. Since the mid-1980s, Perle, an ardent gardener and amateur naturalist, labored intensely to coax her large yard back to what it may have been long before urban sprawl crept into her once-rural community about eight miles from the Wisconsin border. Olsson, who had planted native flowers and grasses and did not want to see her natural garden destroyed, approached the privately run Land Foundation of McHenry County. By offering to donate an easement on her backyard to the foundation, which is one of the many land trusts that have sprouted up in recent years in the Chicago area and across the country, the Olssons can still hold onto their property or eventually will it to family members. However, the easement — which is still being negotiated — will virtually guarantee that the future owners of the property treat the land with like-minded respect.

According to the 1994 National Land Trust Survey, there are now 1,100 similar land trusts across the country, an increase of 23 percent since 1990. Many of these trusts have helped protect more than 4.4 million acres of land in the United States. Under the legal contract for a conservation easement, the land trust agrees to keep an eye on the owner's parcel for future generations. Meanwhile, the landowner's generosity is reflected in the opportunity for state and federal tax deductions. A 1994 state law clarified tax regulations in Illinois for lands encumbered by such an easement. Previously, each county assessor evaluated these properties. With the new law, the property tax assessment is reduced from 33 1/3 percent to 8 1/3 percent of fair market value for lands with a perpetual conservation easement. When a landowner sells or gives such an easement to a public or not-for-profit organization, he or she is forfeiting certain rights for the common good. One of the benefits is that the legal provisions can be tailored to the landowner's wishes. Land that possesses natural, scenic, archaeological, cultural, educational or recreational values may be considered for protection. The tax reduction hinges on whether the parcel provides a "public benefit," but public access is not a requirement. To assist county and state tax officials, the determination as to whether the protected land qualifies for the tax break is made by the Illinois Department of Conservation. If the terms of the easement are perpetual and the property is sold in the future, the restrictions on the land remain in effect. The public agency or not-for-profit organization that accepted or bought the terms of the easement periodically monitors the land for compliance. Land conservation in private hands According to Gretchen Bonfert of Green Strategies, more than 90 percent of the land in Illinois is in private ownership and "the future of land conservation in the state is the private sector." Green Strategies is a Springfield-based consulting firm specializing in land conservation and environmental policy. Bonfert, who served as deputy director of the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission from 1989 to 1993, assisted in clarifying the property tax laws last year for conservation easements. "The future of land conservation in Illinois isn't limited to the important action of saving isolated parcels with rare resources," Bonfert says. "Much more broadly, the land along forested areas, hill prairies, streams, as well as up into watersheds, contributes to the well-being of Illinois' natural landscape. For a willing landowner who is committed to his or her property, a conservation easement can keep it in the family or in the business and ensure that its natural resources remain forever. It's not feasible, nor is it practical, to expect public agencies to acquire all properties that contribute to the conservation of the natural landscape. Typically, the consumer's action in the marketplace makes a statement." 12/July 1995/Illinois Issues She notes, for example, that the increasing appeal of homes in a natural setting inherently involves one or more preservation and conservation tools, such as nature preserve dedication or conservation easements. In just the last few years conservation and residential development interests have converged in such diverse areas as Lake and Cook counties in northeastern Illinois and Menard County in central Illinois. Restricted sites for home construction, offering privacy and access to natural lands using various conservation agreements and land management practices, contribute to a sophisticated rural lifestyle. Though some land trusts have been around for a while, the idea is slowly taking root as the public becomes more educated, says Ders Anderson of the Openlands Project in Chicago. "There really is a learning curve involved," he says. "You need not-for-profits and agencies to explain to property owners this tool that's available. It's a purely voluntary action. Land trusts are not a restriction that someone on the outside is putting on. It's your choice." Even property rights groups think such an agreement is a good deal for everyone involved, as long as the landowner is aware of what he or she is potentially giving up. "We think it's a great idea, if an individual wants to set aside land voluntarily," says Nancie Marzulla, president of the Defenders of Property Rights, a Washington, D.C., group that opposes the government's using purely environmental reasons to infringe on a landowner's rights. "But you should be aware of what you're giving away, because once it's given away, you can't change your mind." One group designed to help landowners find options for their property is the Natural Land Institute of Rockford. The institute — one of the oldest land trusts in the nation — joined forces with land trusts in Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin, hoping to better protect 2.7 million acres of bluffland along the Mississippi River. Over the years, about 13,000 acres of the bluffland — dominated by huge forests and biologically significant streams — have been successfully preserved. Much of the land is a habitat for neo-tropical migrating birds, as well as 45 special-status plant species and 25 special-status animal species, including the Iowa Pleistocene snail, once thought to be extinct but now found in Illinois along the bluffs.

"They [the blufflands] are amazing," says Brian Reilly, the institute's land preservation director. "They weren't touched by the glaciers and the topography is absolutely gorgeous." Reilly works only with willing landowners, offering them such options as easements and nature preserve dedication.

Landowners can also donate their property — or even sell it to the trust at fair market value. "We're a lot like family, and we work with landowners on a personal level," says Reilly of the trust, which helps preserve land in Illinois and southern Wisconsin. "We fully understand that people often can't afford to give away 40 acres of their family farm because it has a rare plant on it — it's just an unreasonable expectation." When Isaac Funk and his brother-in-law, Robert Stubblefield, settled in central Illinois in the mid-1820s, they began amassing what would become a 25,000-acre rural kingdom, an island of timber surrounded by a sea of prairie. Though modem travelers are probably more familiar with the homey billboards that hawk "Maple Sirup" at Funk's Grove off 1-55 about 10 miles south of Bloomington, the natural beauty of the landscape is equally alluring to nature lovers. Every other Saturday, from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m., Schmidt and. a dedicated core of volunteers — about 200 every year — turn out to help with everything from planting seedlings in the newly purchased tract to clearing hawthorns and honey locusts from the adjacent prairie savanna known as the Ewing tract, now owned by the conservation department. Says Eric Funk, "The Nature Conservancy volunteers have provided the bulk of the labor by replanting thousands of trees and making our dream a reality." The 246-acre Sugar Grove tract at Funk's Grove is still being farmed, though gradually it will be restored to its original pre-settlement condition. Though the land will remain in private hands, eventually it will be opened to the public, who could visit a nature center planned for the site. On a warm, breezy Saturday in February, about 20 volunteers turned out to work the adjoining savanna, cutting down such non-indigenous plants as sugar maples that can strangle other important vegetation. "I came here to chop, chop, chop," says Wes Wilcox, who had spent the morning running a power saw and removing some hawthorn and Osage orange trees. Retired from Funk Seeds, Wilcox, in his tobacco-colored jacket and corduroy ball cap, stood blissfully in the adjacent gravel parking lot. "I guess I'm a conservationist at heart," says Wilcox, who was raised in McLean County and still lives nearby. "I love the outdoors and have a long history here. I appreciate this land being restored for future generations to enjoy." * Elizabeth Bettendorf is a reporter for The State Journal-Register in Springfield.

July 1995/Illinois Issues/13

|

|

|