|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By JAMES KROHE Jr.

Not just for field trips

More and more museums are showing schools how to teach science

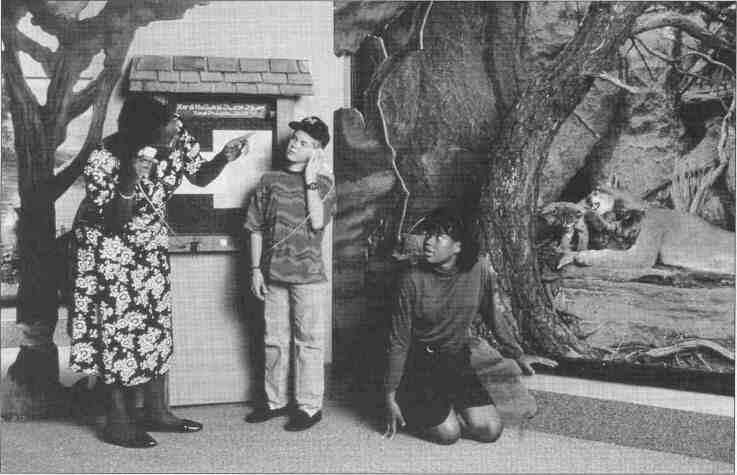

Courtesy of the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Photograph by John Weinstein, ©1992 If there's any dust on museums these days, it's plaster from new construction. In the 1980s the museum biz boomed. New ones opened, old ones expanded, brought on younger staff and shook the cobwebs out of their displays as visitors poured in. Illinois today has a museum for virtually every interest, and at present rates of expansion will soon have a museum for every Illinoisan. Still, the cultural landscape is shifting in ways that are rocking museums' foundations. Audiences are changing, and so are standards of scholarship. Museums face competition from new forms of entertainment — theme parks, TV — that are more educational than traditional museum fare is entertaining. Nor are museums the only repositories of the bizarre and the exotic, as any child learns when she turns on the Discovery Channel or C-SPAN. Funding is iffy too. Corporate and private philanthropy is 14/July 1995/Illinois Issues stretched very thin. (The cumulative goal of capital fund drives now underway for the Museum of Science and Industry and the Art Institute in Chicago is $112 million.) Public funding, more predictably, also is undependable. For a century, Illinois museums were funded the way that one used to automatically tip one's hat to the parson — on the assumption of virtue. But museums are no longer automatically counted among the deserving poor by lawmakers. The Right sees in their well-meant attempts to accommodate Illinois' more urban, polyglot culture proof that museums are agent provocateurs in our PC wars, while the Left sees them as irrelevant to that culture. A lot of people in-between feel the natural resentment felt by the nearly educated for the over-educated. Important factions in the new Congress have targeted for funding cuts the National Science Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Institutes of Health — all substantial funders of museum research, outreach and exhibit projects in Illinois. Museums thus are keen to demonstrate that they have usefulness beyond scholarship and instruction in social manners, now that both of those traditional benefits are temporarily beyond the political pale. Nothing demonstrates a museum's dedication to High Public Purpose more than education. The Art Institute's newest long-range plan, which like those of most of its sisters pledges a renewed emphasis on education, recalls its own 19th-century youth when its collections consisted mainly of plaster casts of Famous Art assembled for students to copy. Museums in those days brought to visitors things they knew about but had not seen. Today they are more often asked to show visitors things they have seen but know nothing about. A spokesperson for the Art Institute explains that the mission of the museum's education department today is still essentially to teach people about its collection. But where coming to the museum used to constitute maybe 10 percent of a child's education in art, now it's often his only education in art. It used to be that an art museum was where one went to see a Monet. Today it is to find out who Monet was. (And in some cases, to find out what a museum is.) A few years ago, the Field Museum surveyed its visitors about the Pacific, which was to be the subject of a major — and controversial — new exhibit. Staff found that while people had heard of the Pacific somewhere, many of them didn't know there was so much water in it or that it had so many islands. One would not think that explaining that the Pacific has a lot of water in it is the best use of an institution that is home to the West's pre-eminent experts on Melanesian cultures, but then buying a computer to teach 4-year-olds how to add two and two isn't very efficient either.

There's one we don't have yet: A museum of misguided pedagogy. Museum ed Education is the sum of the mandate of most of Illinois' newer museums. Scitech, the not-for-profit "science and technology interactive center" in Aurora, was the brainstorm of a senior scientist at Fermilab eager to find ways to cure science illiteracy. The measure of museums' commitment to education may be taken in the lavish provision in new museum buildings such as that being built by Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art for classrooms, lecture halls and libraries. Less visible is the increasing share of the budget and clout that museum education wields at the big museums. Not so long ago a field in which retired teachers might putter productively, museum ed is now an accredited profession. In days past they explained exhibits; today they help design them. Museum News runs articles on human learning by the University of Chicago's unpronounceable expert on "flow," Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, describing how museums might build intrinsic rewards and situational interest into their exhibits along with the humidity controls and lighting. When one visits the Discovery Room in the Illinois State Museum or the Kidspace at Scitech, it is hard not to be impressed with the buzz of committed activity one sees there. It is also hard to not ask why one can't see the same things in every grade school in the state. "Discovery centers" — every museum has one — look like what a grade school science class would look like if schools were as well run as our museums. There being real limits on how many kids one can cram into a museum on field trips — one of those limits being the tolerance of other visitors to having the place turned into a school — less and less of museum education happens inside museums. The Illinois State Museum shares its collection of Illinois arts and crafts via distance-learning networks to (mainly small rural) schools that finally got electricity but don't yet have arts programs. The Field supplies materials to "teach" Africa (required by the Illinois General Assembly, which is quicker to provide mandates than materials). The Art Institute and the Sears Roebuck Foundation provide area schools with 10 framed posters of famous works (mostly from the Institute's own collections). Chicago-area schools incorporate Middle East anthropology into their social studies curricula thanks to the Spertus Museum at the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies. The Museum of Science and Industry sponsors science clubs in neighborhoods throughout the city and supplies them with materials and training. Museums and schools have always worked together of course. Museums offered the chance for an outing, and the

July 1995/Illinois Issues/15

schools offered a way to kite the attendance figures. Today, increasingly, museums are a presence in the day-to-day curriculum. "Synergistic" is a good word to describe a relationship in which museums provide expertise and materials and schools provide civic purpose. Real dirt! Real fun! This evolving relationship benefits museums and school districts, clearly. It also benefits lawmakers and their constituents, who thus can pass off some of the costs of educating the young to private givers (including foundations) and to federal agencies such as the National Science Foundation that fund projects like Scitech. But the real beneficiaries are kids. One museum tradition in particular has reinvigorated museum education, and thus promises to do the same for what we might call school education. That is the museum's focus on the real. In days past, seeing, oh, a wooden buffalo mask of the Bamileke behind glass was as close as one got to it. In the pre-TV era that was enough. But seeing is no longer believing in a TV culture; kids look at amazing stuff behind glass all day long. The Field states that learning is achieved primarily through the object. It certainly is at the Field, an institution that has some 20 million objects in its collections. What scientists know also is known by child development researchers, and by children. Only conventional pedagogy seems not to know this. Thus the trend in museum education toward "hands-on" learning. At Dickson Mounds, visitors may get insights into Indian ways by grinding corn, using a pump drill, honing bone into needles, playing with replicas of ancient toys. In 1989 the ArdFact Center at the Spertus Museum recreated a Near Eastern archaeological dig in which kids dig — real dirt! real fun! — for pot shards that reveal how the ancient peoples of Israel lived. Teens get a chance to actually handle specimens and learn scientific methods at the Illinois State Museum's "Science Connections" workshops. In short, visitors get the chance to do science more the way scientists do it. Done with restraint, such experiences add enormously to "the museum experience." (Most of these activities are aimed at kids, but the Art Institute is not the only museum to find that adults want to get in on some serious fun.) At the Art Institute's Kraft Education Center, copies of major works are displayed near six alcoves. One can pick up an African ceremonial mask, then adjourn to watch a video showing the dance in whose rituals it plays a part. Seeing a Japanese wood block print up close may be augmented by a chance to handle print paper and a wood block, and inspect a print in various stages of production. Here, the real world and the abstract world of image are put back into their proper relation. The best of the museum education programs do not only do more than most schools do. They do it in ways that most schools can't, or won't. For example, museums are abandoning the schools' one-size-fits-all methods. The museum's enduring reputation for boringness is owed in large part to the fact that exhibits were designed for only those visitors who were comfortable with the printed word. Exhibit designers recognize that people learn in different ways. Today, computers, slides, sound tracks, graphics give visitors choices about how to leam. Graphics teach visual learners, words the readers, just as there are techniques geared to the preferences of the listeners, the problem solvers, the touchers, the artists and the builders. Museum educators also are liberated by the setting within which learning happens. The visitor to the museum has choices in what to pay attention to as well as how, plus the freedom — ironically, most constrained on "educational" field trips — to choose how long to pay attention. The Field's president, Willard L. Boyd, drew a sharp distinction between conventional schools and museums in a recent address to an East Coast college of education: "Unlike schooling, learning in a museum is self-motivated, self-directed and can be lifelong." Boyd goes so far as to imagine a future in which museums will have evolved into alternatives to conventional schools by becoming centers of teaching as well as centers of learning. Some Illinois museums already function as parallel schools or community learning centers (phrases used by others in the field who tout the same idea); the steadiest users of the new exhibits at Dickson Mounds Museum, for example, are home-schoolers. It is not hard to foresee a quid pro quo in which school systems would exploit museums' interest in audience building and 16/July 1995/Illinois Issues outreach — and give the latter a new revenue stream — by contracting arts and sciences instruction to them. But reaching more than a few students would require bulking up museum ed departments, which might thus achieve the imbecilities of scale that afflict existing school bureaucracies. Better that the museums stay out of the schools. There is a role for them as laboratories to test new ideas — new to the educational establishment, anyway. It is admittedly a fond hope. Illinois' better private schools have been immersing their students in the real for years, with no apparent impact on mainstream methods. School systems, like kids, apparently learn better by doing than by example. A more promising role for museums is as an alternative to another discredited branch of American pedagogy, teachers' colleges. Museums have already attracted a cadre of committed teachers — it is hard not to think of them as subversives — who are eager to learn better ways of doing their jobs. Two examples of several: The Illinois State Museum in 1992-93 drew 300 people to week-long science literacy training institutes for teachers, funded by the State Board of Education, and the Art Institute busily produces teacher manuals and various courses for teachers, some of them for credit. Having excited the best with new ideas about teaching, perhaps our museums can help raise the rest. * James Krohe Jr. is a contributing editor of Illinois Issues.

July 1995/Illinois Issues/17

|

|

|