|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By TARA McCLELLAN McANDREW

Making history

When historic site interpreters try to entertain visitors,

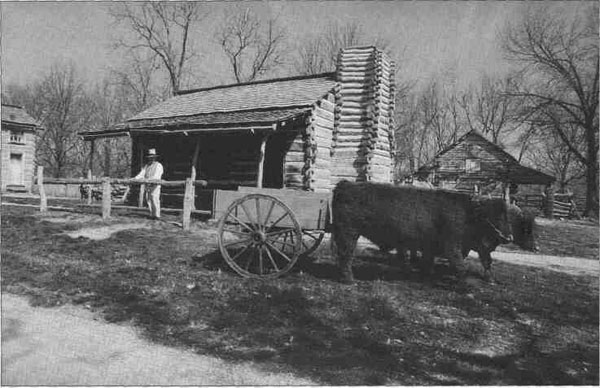

Courtesy of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency "Did you see today's paper?" the woman asks a visitor as he enters her log cabin in New Salem. "You should check this list of people who haven't picked up their mail at the post office to make sure you're not on it," she says, pointing to an 1832 issue of the area paper, the Sangamo Journal. The costumed interpreter then explains to the visitor how mail was delivered in the old days at New Salem, a reconstructed prairie village near Springfield, where Abraham Lincoln lived before moving to the state's capital. Lincoln's New Salem State Historic Site is just one of Illinois' 57 historic sites and memorials, an inventory that includes Ulysses S. Grant's home in Galena at our northwest border and the Buel House in Golconda on the Cherokee Trail of Tears along our southern tip. The sites attempt to tell the story of our distant past, represented by the native people who lived at Cahokia Mounds, through our recent past, represented by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Springfield. New Salem represents the 1830s, when Abraham Lincoln was a young man, and it attracts the most visitors of all of the state's historic sites, according to David Blanchette, spokesman for the Illinois His- 18/July 1995/Illinois Issues tone Preservation Agency. While all the sites attract a combined three million visitors each year, Blanchette says. New Salem alone draws 600,000. Yet, while the encounter with the New Salem "resident" may seem innocuous enough to most casual visitors, it raises some key issues among public and academic historians alike about the role of such sites. What is, or should be, the state's purpose in interpreting the past? Is the role of a historic site primarily to educate us? To entertain us? To raise dollars for the state through economic development and tourism? Can these sometimes competing agendas be balanced? And how does that effort affect our understanding of the past? Scholars and history professionals — known as public historians — point to a long list of benefits in government-sponsored sites. Education is at the top of the list. They also cite preservation of old buildings, equipment, tools and other material items of everyday life; economic development; promotion of state and national identity; and even healing — the national Vietnam Veterans Memorial is cited as one example of history as catharsis. But some of these roles can be in conflict. The pressure to make historic sites entertaining inevitably alters the presentation of history; the need to package, even market history necessarily has an impact on the representation, and ultimately our understanding of the past. In fact, public historians haven't sorted these issues out. They continue to debate among themselves what does and should happen when the historian meets the public. As the person responsible for helping sites develop their interpretive programs, Richard S. Taylor of the preservation agency has given considerable thought to the matter. He believes it's impossible to completely and accurately represent the past. As a result, Taylor believes public historians have some latitude to experiment with more effective ways to draw people to history. According to Taylor, there are two standard methods for presenting history at sites: first-person interpretation, where staff members or volunteers portray characters from the past, and third-person interpretation, the traditional lecture/tour approach. The encounter at New Salem illustrates a third approach, called "interpretive theatre." That approach combines first- and third-person interpretation and re-enactments of events from New Salem's past, including a wedding and a temperance sermon. While Taylor advocates all modes of interpretation, as long as they fit the particular needs of the individual historic site, he wanted to try the new approach at New Salem for several reasons: It would enliven the presentation and raise the morale of interpreters — the lecture-style approach can be too repetititive for them — and he believed it would create a better learning environment for the public. "We wanted to put a little life into our program, to make it more palatable for the visitors," says David Hedrick, site manager at New Salem. "We have noticed sometimes here and at other sites around the country that history can really be boring. Sure the information is interesting, but the manner in which it's presented can really affect how enjoyable and palatable it is for the visitors." And how effective the educational mission is. "You're trying to share this information with a public that doesn't have to listen to you," says Patricia Mooney-Melvin, past president of the National Council on Public History and associate professor of history at Loyola University in Chicago, where she directs the public history program. "Just kind of shoving information down people's throats is not necessarily going to bring understanding," says Mooney-Melvin. With that problem in mind, the state's historic preservation agency hired Phil Funkenbusch, a Havana, Ill., native with an extensive theater background, as chief of interpretive theatre. Funkenbusch explains that he works with New Salem interpreters to make the site "more like a real village." Interpreters stroll around, greeting one another and visitors. "I want the public to feel comfortable being able to ask questions about New Salem, because the more comfortable they are, the more apt they are to ask questions and learn something," Funkenbusch says.

Most of the state's sites still use the traditional lecture-style presentation, although some have switched to first-person, a method that has become more popular across the country. And, while critics say the new methods of interpretation lean too far toward entertainment and too far away from historical accuracy, advocates point to public response. "They love it," Hedrick says of the tourists who put New Salem at the top of the popularity list. And the politicians who fund historic sites love the tourists. Susan Mogerman, the director of the Historic Preservation Agency, says when she defends her agency's budget to state lawmakers each year, the argument they respond to the most is her agency's economic impact around the state. "They do enjoy the connections for education, as well," she says. But in order to have an economic impact, historic sites have to attract visitors. In order to do that they have to be competitive in the way they present programs, especially with leisure time decreasing and leisure time options increasing. "We're competing with Disneyland, lakes in Wisconsin, casino boats and the like, so we have to have a program that's both entertaining and worthwhile," Mogerman says. "You can't have display boxes [at historic sites] anymore and expect people to go home thrilled." Tom Vance, manager at the Lincoln Log Cabin State Historic Site in Lema, agrees. He switched the approach at that site from third-person to first-person in 1981. "People expect to be entertained," he says. "So if you can get history across in an entertaining and accurate way, you're going to be more effective." Vance believes the switch in interpretive method partially accounts for increased attendance at his site.

July 1995/Illinois Issues/19

Mogerman, Vance and historic preservation agency employees associated with New Salem say that education and preservation remain the top considerations at the state's sites. Nevertheless, professor John Bodnar, who specializes in American history at Indiana University in Bloomington, raises a few warning flags about government-sponsored history. He believes the overall educational mission can be jeopardized if, under political pressure, government loses sight of that priority. "If funding for state sites is totally controlled by interests that want to generate more tourism, then obviously the history is going to serve those interests and be more appealing and exotic than one that is more balanced in terms of what went on." At the other extreme, Bodnar points to the dangers of complete privatization of historic interpretation. He cites Disney World as an example of a commercial venture that idealizes and fictionalizes small-town America, or the world created at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, a privately funded site that until recently gave a romanticized and sanitized version of the past. "For many years there was the preservation of a southern town in the colonial era with no record of slavery, though that eventually changed," Bodnar says, referring to Williamsburg's recent increased attention to slavery in its interpretive programs. That shift, it should be noted* caused considerable public controversy. But government can play the role of mediator among a community's contending views of the past. Bodnar and Mooney-Melvin say, in fact, that government's role is to make certain as many views of the past as possible are presented at historic sites. This way, Mooney-Melvin says, "the public gets a deeper understanding of the dynamics of the past than they would if they're given a song and dance, like, 'This is the way it is.'" Bodnar adds that to achieve that inclusiveness requires input from scholars and the public. In fact, public input is increasingly serving as a check on the content of presentations at public and private historic sites. A recent example is the controversy over the Enola Gay exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution's Air and Space Museum. The debate centered on the meaning of the bombing of Hiroshima. Veterans challenged the Smithsonian's version. Ultimately Congress stepped in and the exhibit was revised. Marcia D. Young, manager for the David Davis Mansion State Historic Site in Bloomington, says that controversy and others like it raise an important question: "Who owns history?" It strikes at the heart of power and control over our understanding of the past, she says. "Are scholars' expertise and training more valid than any other consideration? Or does the community's personal memory and the community's meaning [of the past] have a role to play in its presentation?" she asks, adding that she believes the public will become more involved with defining the content of history, to the point of helping government and scholars develop historic exhibitions from their inception.

The Enola Gay exhibition was an example of a forceful effort to claim history. But the public has been claiming it in more subtle ways for a long time; a good example of this is what happens at New Salem, according to Edward M. Bruner, University of Illinois emeritus professor of anthropology. In a 1993 article about New Salem in Museum Anthropology, Bruner wrote that a conflict between the popular and the scholarly is enacted daily at the site because "the parties involved have their own interests." So, despite the efforts of scholars and historians to present an "accurate" view of New Salem, for many reasons visitors may come away with a view that is technically "inaccurate." One reason is the way in which volunteer interpreters portray the past. Largely because of local pride, volunteer interpreters, consciously or otherwise, portray New Salem as the site that created Lincoln, the future leader of our nation. It's "the familiar American rags-to-riches success story," Bruner wrote. But, he added, academic historians say New Salem's importance in Lincoln's future may have been overemphasized. However, tourists come to New Salem because they want to see that American success story and local volunteers want them to see it, too. So, people often see what they want to see at historic sites, despite the efforts of scholars or public historians. "People are going to use the sites for all sorts of reasons, for their own agendas," Bodnar says. He cites as an example the ways in which Lincoln has been appropriated by different groups to meet different needs: as a symbol of unity or of freedom. Still, government can serve as a forum for the diverse communities in our country to decide what's important about our past. And, ideally, the sites can present history in a manner that's conducive to understanding. Meanwhile, attendance at all state historic sites is up by 16 percent this year, according to the Historic Preservation Agency. David Blanchette says the agency thinks the rise is due to the Illinois Department of Commerce and Community Affairs' increased tourism promotion and to a resurgence of interest in Lincoln. Such interest always increases when there are freedom movements anywhere in the world, he says. (On a less lofty note, the baseball strike may have helped. There have been reports that the public's continuing strike against baseball has increased attendance at other leisure-time venues.) Attendance at New Salem is up even more than at the other state historic sites. It has increased 20 percent so far this year. The lesson? Maybe the public likes its history served with a dollop of entertainment. * Tara McClellan McAndrew is a free-lance writer who specializes in writing about culture and the arts. As a lifelong resident of Springfield she's visited New Salem many times and has experienced both of the interpretive approaches. 20/July 1995/Illinois Issues |

|

|