|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Summer Book Section

When the messengers become the message By RONALD DeBROCK William E. Shaw and Boris Ivanov, eds. From Fear to Friendship. Chicago and LaSalle: Open Court Press, 1994. Pp. 224 with illustrations and appendix. $41.95 (cloth); $17.95 (paper). Although newspaper people relish a good tale, they habitually shy away from telling their own stories. That barrier is one of many William "Bill" Shaw and Boris Ivanov overcame when they wrote From Fear to Friendship, a first-hand account of two newspapers' involvement during the mid-1980s thaw in relations between the United States and the former Soviet Union. Providence penned more of this story than its authors, but their personal involvement in the tale provides readers with an insider's look at the puzzles of international politics. Although Ivanov grew up in Siberia, arguably the harshest home a person could have, he benefited from the Soviet selective educational system and studied journalism at the Khabarovsk Institute before becoming news director of Krashnoyarsk Television. In 1986, he was a correspondent for the Novosti Press Agency when he read a weekly newspaper's story titled "Dixon: A Town of Lost Hopes." The story, which had run earlier in the London Sunday Times, gave an antagonistic appraisal of the Illinois town cited as the birthplace of then-President Ronald Reagan. In actuality, Tampico was Reagan's birthplace; Dixon was his boyhood home. Other newspaper stories of the day covered the cautious optimism of the world's top two leaders, Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. But the melancholy portrait of Dixon was what fascinated Ivanov and his fellow journalist Sergei Ostroumov. The latter suggested that an exchange between Dixon, Ill., and Dikson, Siberia, might aid world peace efforts in a small but symbolic way. Ivanov composed a letter of introduction from Dikson to Dixon, and in December 1986, the message was sent to Shaw's newspaper, The Telegraph. Unfortunately, the letter was addressed to Ben Shaw, Bill Shaw's late uncle, who had formerly held the same Telegraph publisher's post. As newspaper people are wont to do with inadequately addressed mail, Bill Shaw tossed Ivanov's letter in the trash. The story might have ended there, but fortunately Shaw's curiosity overcame his haste. A past president of the Illinois Press Association and a director of the National Newspaper Association, he reflected on the Ivanov letter's return address — the Soviet Embassy, Washington D.C. — and retrieved the discarded invitation. Scanning it with an editor's eye, he stopped at the word "Dixon." With piqued interest, he ran the letter on the front page of the next Telegraph. Mayor James Dixon, a descendant of the town's founder, responded with an official greeting to the Siberian city a few days later. And on March 15, 1987, Moscow's Komsomolskaya Pravda ran a three-paragraph story on the letter's receipt, completing the initial two-way communication between Dikson and Dixon. Time trudged on as an international exchange of pen pal missives between Ivanov and Shaw was played out in both communities' newspapers. After months of Soviet scrutiny and northern Illinois nay-saying, Dixon officials hosted Dikson officials in August 1988. Tales from the Dixon contingent's trip to Dikson's Arctic Circle community in April 1989 relay that residents' personal warmth is their greatest source of heat. Images of Illinois bed-and-breakfasts are pushed aside for polar bears and Kara Sea icebreakers. The fertile fields that honed John Deere are contrasted with the forever frozen Siberian soil. The authors take turns at their literary podium to share impressions and injuries harvested from their seeds of peace. Ignorance, prejudice and vanity aren't sins confined to cities. Shaw shares some not-so-favorable sentiments of his neighbors on the Soviets' visit, and Ivanov enlightens free-to-roam readers about the asperities of international travel. Their stories, however, hold strong to the optimism that initiated the sister cities' union. Comments and observations obtained from others, including insights from Reagan, flesh out the success story with real-world hopes noticeably lacking in politically correct puffery. Photos enhance the duo's messages of contrast and compromise, allowing readers to learn about both communities and their cultures. But the two towns' truest images are found in the captured voices of their residents. Teaspoon tastes of their counterparts' cultures provide the essential ingredients for Shaw and Ivanov's recipe for successful relationships between nations. The urge to use the sister cities as models, however, is tempered by the authors' realistic appraisals of today's politically hamstrung world. But given the hopeful beginnings of their book, Shaw and Ivanov may prove that even fate can be overcome by people with a shared goal. Ronald DeBrock is publications manager for the Illinois Press Association. He was a small-town newspaper editor from 1985 through 1994. 24/July 1995/Illinois Issues

A simpler time:

By ETHAN LEWIS Douglas Clayton. Floyd Dell: The Life and Times of an American Radical. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1994. Pp. 335 with photographs, notes and index. $30 (cloth). In an all-too-real sense, Floyd Dell (1887-1969) followed the heroine he created. Shortly after Dell and Diana Stair (1932) revived the historical novel — and so broke ground for John DOS Passes and Howard Fast, and later, Gore Vidal, James Michener and E.L. Doctorow — he became history, his name found solely in notes on the Chicago Renaissance. Yet, according to biographer Douglas Clayton, who has taught literature at Northwestern University and the University of Illinois at Chicago, this author, editor and "salon raconteur" best evinced the endeavor in this nation "to understand culture in relation to society." Clayton's monograph successfully recenters a hub of modern American thought. The Life and Times also captures Dell's internal struggle to reconcile ostensibly conflicting causes: bohemianism with socialism; self-absorption with public commitment. Clayton crisply depicts Dell's innately intellectual nature. From childhood, Dell felt driven to systematically explain things. Rather than ascribe his parents' poverty to poor character, for instance, he located the cause in capitalist inequity. "Through socialism Floyd found a key to understanding what had previously prompted only bewilderment, shame, and inarticulate rage," Clayton concludes. Dell would later formulate his worldview as editor of The Masses and Liberator, powerful socialist organs under his leadership.

The pattern repeats when Dell submits to Freudian analysis in order to overcome habitual infidelity. Personal and social outcomes again reflect each other; psychoanalyze oneself, Floyd figures, and one can better explicate the world: "Here was an idea of the same importance as the Copernican idea, the Darwinian idea, the Marxian idea — destined, like them, to revolutionize human thought in a thousand ways. My mind leaped to grasp the multiform significance of this new truth." Dell's once influential tomes on education and the family emerged from couch-work as much as desk-work. Even so, Dell always tempered his belief in explanatory models with a wariness of dogma. A champion of the Left, modern art, feminism, educational reform and (to some extent) free love, he maintained what so many of his comrades in these causes lacked: the detachment to criticize and question. This balance renders Dell an intellectual hero in Clayton's eyes, in the tradition of Dell's fellow critic Randolph Bourne and of Dell's proteges, author-activists Joseph Freeman and Dorothy Day. Given the candidness of Clayton's portrayal, the reader will likely see his subject in a similar light. The book has more than its discerning profile of Dell to recommend it. It treats the times of this American radical through deft portraits of the figures surrounding him. Perhaps the more integral cast members — Dell's Civil War veteran father,

July 1995/Illinois Issues/25

Summer Book Section

his wives Margery Currey and B. Marie Gage, his lifetime friend-and-nemesis George Cram Cook, the playwright — will upstage others. But I am struck particularly by the fleeting glimpses of the famous: Theodore Dreiser folding and unfolding his handkerchief; Sherwood Anderson, too scared at first to venture past the Dell's door; the "intoxicating ... unwholesome" Edna St. Vincent Millay lighting candles in Greenwich Village. Of Clayton, one might echo Dell's remark on what in Dreiser most impressed him: an "ability to capture with lifelike precision the features of his ... characters in terms of their connection with the facts and details of the new American scene." Of course, such cameos also showcase Dell in the middle of his milieu. The times, moreover, seem caught in microcosm, on occasion in remarkably complex ways. The chapter "Wartime," for instance, treats the first world war indirectly, through detailed coverage of three other battles — between writers and artists at The Masses; between editors of that monthly and the U.S. government, which tried the editorial board on treason charges; and between Dell and Millay, whose affair smacks of love as war. The report from that front relies on reading a writer's life through his work: here, specifically, through interpretation of the sonnets Dell composed about Millay. A standard if somewhat risky ploy, utilized by Clayton throughout, such reading between the biographical subject's lines was sanctioned by Dell, who championed literary expressionism and realism as writer and critic. That the Dell story entertains, and that Clayton tells it well, surpass doubt. One even detects in it a bit of Horatio Alger that endures (and endears) beyond the complexities of the narrative. When young Floyd applies for a printer's job and gets hired as a cub reporter; when Dell later happens by the restaurant window behind which The Masses brain trust has just decided to find a new editor; when at lowest romantic ebb he meets B. Marie, with whom he'll spend the rest of his life — we yearn for Dell's times, which, radical though they were, seem simpler than our own. Ethan Lewis is assistant professor of English at the University of Illinois at Springfield.

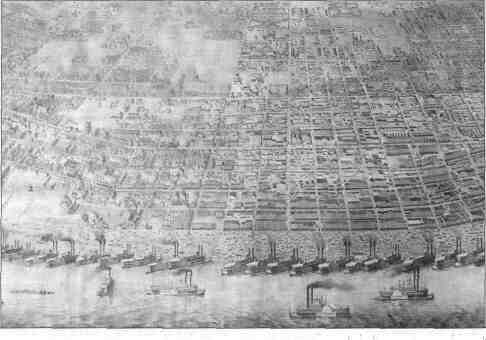

John Reps presents a new view of Old Man River and its towns By WILLIAM D. WARREN John W. Reps. Cities of the Mississippi: Nineteenth-Century Images of Urban Development, with modern photographs from the air by Alex MacLean. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1994. Pp. 342 with introduction, bibliography and index. $59.95 (cloth). If you have ever lived along the Mississippi River, or if you have ever had an interest in the Mississippi Valley, you will find viewing and reading Cities of the Mississippi fascinating. John Reps, professor emeritus of city and regional planning at Cornell University, is the established master in the art of assembling and presenting visual materials on the physical development of cities. His previous publications on cities and urban planning include The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States (1965), Town Planning in Frontier America (1969) and St. Louis Illustrated: Nineteenth-Century Engravings and Lithographs of a Mississippi River Metropolis (1989). The period covered by the latest volume in this outstanding series on the history of the American city starts with the purchase of the Louisiana Territory in 1803, and the development of the region's riverboat towns during the 19th century provides the book's primary focus. By the century's second decade Robert Fulton's steamboat was clearly established as the dominant means of transportation along the southern section of the river. Reps follows the south-to-north axis of urban growth that was stimulated by the river's extraordinary commercial development. By 1848 an image of traffic congestion is clearly apparent in the views provided by Cities on the Mississippi. The volume offers an initial narrative section, followed by a series of 65 tours or portfolios presenting images of the cities that developed along the river during the 19th century. Perspective renderings, maps, photographs and other sketched material comprise the folios, some of which contain as many as 16 illustrations. The narrative section discusses the artists that produced the imagery in the folio sec-

Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society This detail is called Bird's Eye View of St. Louis, Mo. James T. Palmatary drew it in 1858. 26/July 1995/Illinois Issues tion. Anecdotal material details the backgrounds, travels and experiences of the illustrators. Useful information is also presented regarding techniques that were used for preparing the illustrations. The folios will hold the greatest interest for most readers. Beginning with New Orleans, the folios proceed city by city upstream to St. Cloud, Minn. Many of the images are in color, which adds to their interpretive qualities. A wealth of written information is included in each folio. Travelers' accounts and details regarding aspects of the imagery are included in each tour. This gives the reader an alternative perspective regarding the places that are being exhibited. Through this medium Reps illustrates the character of the communities. For example, in Alton, Ill., in 1881 William Glazier reported enterprises that included castor-oil mills, foundries, steam saw mills, woolen mills and agricultural implement factories. Most of these manufacturers have long since left Alton. One of the volume's most remarkable features is the congruence between some of the oblique perspectives and the aerial photographs. For example, the view of Cairo produced by the artist's eye in 1888 is almost perfectly replicated by the aerial photograph taken 100 years later. A comparison of the images illustrates that the configuration of the city's boundaries and the location of buildings have hardly changed. The railway roundhouse for servicing steam locomotives has been removed. Instead of side-wheelers and stern-wheelers, barges now line the levee. Several new factories front the river bank. Nevertheless, the two views are very similar even though they are separated by a century. The presentation of the illustrated material is generally excellent except for one oblique aerial photograph of St. Paul, Minn. (page 307) that seems to be out of focus. Twin-stacked side-wheeler steamboats appear in most of the book's images. The river's traffic densities attained high levels as commercial traffic burgeoned. The impact of the Civil War and the introduction of reliable railway services after 1865 gradually muted this pattern of regional development. Railways changed the orientation of transportation from South-North to East-West. Many of the smaller river cities declined, while the larger ones pursued new economic activities. By the end of the century the zenith of the steamboat era was ending. The primary attractions of Cities of the Mississippi are its images and views. Readers who carefully examine the illustrations of the 65 featured cities gain a unique perception of their individual character and a new appreciation of the development of urban life along the Mississippi River during the riverboat century. William D. Warren is professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Illinois at Springfield. He has published articles on the subjects of cities, planning and transportation.

New Yorker writer shaped by an Illinois childhood By BARBARA BURKHARDT William Maxwell. All the Days and Nights: The Collected Stories. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995. Pp.415. $25 (cloth). William Maxwell, now 86, recently told a national radio audience that "being an old man is the most interesting thing that's ever happened to [him]." All the stages of life seem to coexist, he has said; the past is as real as the present and the two "pass so easily into each other without any effort at all." In the author's latest book. All the Days and Nights, the definitive collection of his short fiction, his past and present works mingle in a similar way. The volume gathers stories from 1939 to 1992 and joins the world of his Illinois childhood with the New York he has known as home since the mid-30s. Maxwell was born in Lincoln in 1908, and, following his mother's death during the 1918 influenza epidemic, he moved to Chicago with his newly remarried father and family. He graduated from the University of Illinois in 1930 with a scholarship to Harvard. After receiving his master's degree, he returned to the U of I for his Ph.D., but left a year later to pursue a literary career in New York. In the midst of the Depression, with jobs scarce, Maxwell boarded a schooner headed for the Caribbean in hopes of finding something to write about at sea. "I had no idea that three-quarters of the material I would need for the rest of my writing life was already at my disposal," he writes in the collection's preface.

July 1995/Illinois Issues/27

Summer Book Section

Indeed, Maxwell's Illinois childhood has provided the foundation for a writing career that has spanned 60 years. Even at The New Yorker — where, as a fiction editor, he helped shape the work of such writers as John Updike, John Cheever and Eudora Welty — he most often published pieces that recalled the prairie town he knew during the early decades of this century. The family and community, the simple, everyday details that make up what he calls "the Natural History of home," inspired four novels — including the award-winning So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980) — as well as a number of the stories in this volume. All the Days and Nights is unified by a sensibility, a state of mind that emanates from the Illinois of Maxwell's boyhood, yet extends far beyond its borders. In essence, the collection offers a panoramic view of the author's literary landscape: The "Natural History" of his Midwestern home remains the core of his fiction, yet other stories portray the anxieties of life on the upper East Side of Manhattan, as well as the adventures and disappointments of Americans travelling in postwar Europe. In fact. Maxwell chronicles a broader sweep of life than may be initially apparent. The stories present finely detailed glimpses of 20th century American experience: from the emergence of Freudian thought and heightened psychological awareness to the struggles of African Americans; from the artist's role in capitalist society to the rhythms of family interaction. The sequence of stories also reveals gradual changes in Maxwell's writing. A first-person narrator emerges who embodies the writer's own sensibilities. Later pieces illustrate an intensified concern with interpreting the past as well as a postmodern focus on the intersection of art, life and memory. More than any single Maxwell volume, All the Days captures the dimensions of the author's world and elucidates his narrative development over six decades. While concerned with the nuances of characters' inner experience, with the fragile beauty and gentle humor of everyday existence, Maxwell never neglects the threatening world that can ravage lives without warning. In "Over by the River," Iris and George Carrington grapple with the challenges of raising two young daughters in a Manhattan brownstone. Inside the apartment the daughters suffer from tiger-filled nightmares and persistent viruses, while outside cries for help pierce the night, the neighbor's cook commits suicide and an emaciated junkie with a switchblade lurks in the neighborhood. Still, George and other fathers rehearse earnestly for the school Christmas program. During their graduation ceremony, the daughters — dressed in pastel costumes and "holding arches of crepe paper flowers" — make their way to the stage as Class One becomes Class Two, and Class Two becomes Class Three. Wiping his eyes with a handkerchief, George realizes "it was their eagerness that undid him. Their absolute trust in the Arrangements." "The Lily-White Boys" also poignantly juxtaposes family tenderness and urban terror. On returning from a party Christmas Day, the Colemans find that robbers have left their home in shambles — mattresses pulled from beds and slashed with razors, drawers turned upside down, his clothes taken, hers spilled across the floor. Yet when the police have gone, Dan Coleman observes from the stairs that Celia is wearing an evening dress he hasn't seen in 20 years; with love and admiration — and without her noticing — he looks on as she systematically dons all the favorite gowns that had been "languishing on the top shelf of her closet" for years. "As she stepped back to consider critically the effect of a white silk evening suit, her high heels ground splinters of glass into the bedroom rug." Such tension between the piercing beauty and haunting sadness of human existence provides drama that courses beneath Maxwell's spare, restrained, yet graceful prose. The writer's Illinois stories also delicately balance life's joys and tragedies. In "The Man in the Moon," the author as narrator proclaims that "the view after seventy is breathtaking" — and from the perspective of memory he preserves the experience of Lincoln's first African- American doctor, Billie Dyer, forgotten in the county history book. From this vantage point, he also sees misdeeds and misfortunes he cannot appease. "The Holy Terror" reveals the startling mistreatment of his brother's leg injury at the hands of a morphine-addicted doctor. "Love" provides a portrait of Miss Vera Brown, the writer's fifth-grade teacher, who dies of tuberculosis at age 23. Throughout the collection, one senses relationships among characters in different stories as well as the author's redevelopment and reinterpretation of autobiographical material. Once acquainted with Maxwell's fictional territory, we begin to focus on his narrative, on how his writing allows him — and us — to continually refine and deepen our understanding of experience. The volume closes with 21 "improvisations" drawn from stories Maxwell has told his wife or written for her on special occasions. There is a purity about these little fables — as he describes their genesis, they were not shaped with the writer's creative control, but, like oral storytelling, are "in direct contact with the unconscious mind." So it is not surprising to find embedded in them the concerns that underscore the author's fiction and thought. Two have particular resonance: The title piece tells of a man who magically learns that all the days and nights of his life continue to be with him, each day "connected to the one before and the one that comes after, like bars of music." And in the hypnotic "The sound of waves," a man and his wife listen as the sea's undulations seem to say, "This year, and next year, and last year, and the year before that, and the year after next, and before they came, and after they had gone. ..." For Maxwell, this year seems particularly focused on connections among his many years. In October, Bun, a children's story written decades ago, will be published for the first time. Based on the author's memory of a neighbor dog who lived in a playhouse made of two piano boxes, the story will be illustrated by James Stevenson, who has 35 children's books, including one by Dr. Seuss, to his credit. Prompting further affinity with the ever-present past. Bun, and the piano-box playhouse Maxwell loved as a child, reappear in All the Days and Nights. The collection provides an eloquent and thorough introduction to the author's work. Yet perhaps most definitively, it highlights important connections in his canon — and presents an occasion to reconsider the rich body of fiction Maxwell leaves as his legacy. Barbara Burkhardt is a visiting assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and teaches American literature at the U of I at Springfield. She is currently writing a critical biography of William Maxwell. 28/July 1995/Illinois Issues New biography of Al Capone reflects a trend in crime history By GEORGE HAGENAUER Laurence Bergreen. Capone: The Man and the Era. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994. Pp. 701 with illustrations, geneology, notes on sources, selected biblography and index. $30 (cloth). For years, crime history books often lacked dates, people's proper identification and an accurate chronology of events. Laurence Bergreen's Capone: The Man and the Era is the third Capone book in recent years to reflect a new trend — well researched crime biographies with copious footnotes and references. Source identification is crucial in crime histories because most of their original sources are criminals, corrupt cops, politicians and newspaper reporters of the period — people who lie for a living, or at best elaborate on the truth. This is why today, many Chicago crime buffs still argue over how much involvement Al Capone actually had in the St. Valentine's Day massacre. The strongest portions of Bergreen's book are those where he has been able to bypass newspaper stories and crime memoirs to access and analyze government documents. One of his discoveries is that Capone used cocaine, a drug habit that may help explain his rapid mood swings and instability as a gangleader.

An additional problem in writing about Capone is that he, more than any other gangster, used the media to shape his own image. Through the many interviews that he granted, Capone effectively buried the real "Capone" from view. Bergreen's contacts with Capone's non-gangster neighbors and distant relatives provide some new insight into the non-criminal aspect of his existence. Bergreen's interviews with the little people in Capone's life, and especially his extensive discussion of Capone's lawman brother Vincenzo, provide a nice balance to his quotes from Capone's public relations machine. Bergreen also offers the most extensive presentation to date of Capone's later life, his years in prison and as an invalid at home. Bergreen, however, misses some major opportunities. After advancing the hypothesis that little-known Chicago Heights mobster Frankie LaPorte was the real power behind Capone, he provides few details and virtually no hard data to support this speculation. His coverage on Eliot Ness, more extensive than in any other book about Capone, also repeats mistakes commonly made about Ness. Most of the recent writing about Ness, including Bergreen's, has been in response to the legend Hollywood created after Ness' death and has been strongly biased by Ness' later years as an alcoholic and failed businessman. Ness' performance as a Prohibition agent (when presumably he didn't drink or drank very little) and in his early gang-busting years in Cleveland (before he became a serious alcoholic) was that of a skilled, innovative, university-trained criminologist. Many early references to Ness' book The Untouchables call it a novel. Since it was fictionalized from Ness' scrapbooks, the book has also been sold as non-fiction

July 1995/Illinois Issues/29

Summer Book Section — "Ness' own account of his battle with Al Capone." Why Ness presented his story as fiction is unknown, but the rights to novels are more easily controlled and sold as films than those to nonfiction works. Whatever its status, Bergreen quotes too much from The Untouchables and in doing so misrepresents a number of events, including giving credence to Ness' famous parade of beer trucks past Capone's headquarters, an incident that is probably apocryphal. Bergreen also detaches Ness' investigation in Chicago Heights from the successful raid by George E. Q. Johnson when, in fact, they were part of the same campaign. Likewise, Bergreen restates the common charge that Ness was a publicity hound who endangered his squad's effectiveness. In fact, there was virtually no press about Ness until after Capone was indicted. In creating The Chicago Mob Wars card set for the tourist trade, I could not find one photo of an actual Ness raid because the press were alerted only after the raids. Post-raid publicity probably was designed by Ness' boss and brother-in-law Alexander Jamie to obtain additional resources for fighting Capone. Jamie had saved his job and become chief Prohibition agent by using the press to advance his cause. This was a strategy Ness had also used in his early years in Cleveland. His famous Cleveland Harvard Club raid occurred while the City Council was considering Ness' massive proposed budget increases to modernize the Police Department. Likewise, Ness' publicized raids against Capone all occurred after his indictment. While they could have reflected a publicity-hungry ego, they also could have been part of a strategy to focus Capone's attention on the lesser Prohibition indictment as opposed to the real priority — the income tax evasion charge. These faults mar an otherwise excellent biography of Capone, a worthy addition to any reference library on crime, and a good read for any student of Chicago history. Former Chicagoan George Hagenauer currently lives in Verona, Wis. He has spent 15 years assisting Max Allan Collins with historical research for the Nate Heller and Eliot Ness detective novels. His uncle grew up living next door to Eliot Ness and his grandfather attended the same church as Mrs. Al (Mae) Capone.

Seeing southern Illinois through a camera's eye By DAVID KENNEY Ned Trovillion. Southern Illinois: A Photographer's Love for the Countryside and Its Beauty. Vienna, Illinois: Cache River Press, 1995. Pp. 112 with preface by the author and introduction by U.S. Congressman Glenn Poshard. $34.95 (cloth); $24.95 (paper). C. William Horrell. Southern Illinois Coal: A Portfolio. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995. Pp. 107 with foreword by Jeffrey L. Horrell and introduction by Herbert K. Russell. $39.95 (cloth). I do not know if Ned Trovillion and Bill Horrell ever met. Since the two shared a strong interest in photography and both lived in southern Illinois, I suspect that they did. I do know that they grew up not so very far apart during the Great Depression of the 1930s — Ned in Pope County and Bill in Union County, Ill. The two, oddly, have something else in common. The first camera each acquired as a teenager cost 12 dollars and change. Bill received his as a high school graduation gift from his mother — it was a folding Kodak 120. Ned, inspired by issues of the newly established Life magazine handed him by his aunt, bought his for himself — an Argus 35mm Candid — while he was in high school. In both families, $12 was a lot of money in those days. Perhaps the choices of and the differences between those two cameras help explain the divergent life courses that Trovillion and Horrell followed, and the contrasting kinds of images they came to value. These two books of photographs about southern Illinois are different in almost every respect. Both are engaging; when the viewer takes them up the pages turn quickly. But there the similarity ends. Ned Trovillion taught agriculture in high school for a time, and then began a 30-year career with the U.S. Soil Conservation Service in Vienna, Ill. All the while he was making images with his series of cameras until eventually he had accumulated a file of more than 200,000. 30/July 1995/Illinois Issues Bill Horrell became a teacher of photography. Most of his students for three decades called him "Doc." (When I first knew him more than 50 years ago it was as "Bill," and I have never known what the "C." stood for.) Almost all of his professional life was spent on the faculty of Southern Illinois University. The fact that he had earned a degree in sociology there may help explain the directions his work took. As an educator he was effective and popular; his published books were used nationwide. As a photographer he was professional and proficient; yet his lifetime collection of retained negatives totaled only 10,000. Trovillion's book is a feast for the eye. A fourth generation native of southern Illinois, he has a keen sense of the uniqueness of the area. In his preface he writes, "I instinctively feel that Southern Illinois is a different kind of place — unique in the nation." It is in fact sparsely populated, rustic, full of scenic wonders so understated and subdued that often only long acquaintance with them brings real appreciation. His subjects are eclectic. Man-made structures, rocky bluffs, rivers, waterfalls (no matter that they spill water only rarely), wild flowers, turtles, butterflies, birds — all appear on these pages. His use of color is richly done, on a few pages almost too much so. Trovillion's book would be improved by at least a few lines of text accompanying each print, better to orient the viewer to the images he sees. It also seems to lack any kind of structure. It is almost as if he had selected his favorite images and then allowed chance to dictate the order of their printing. Still, to turn his pages slowly, savoring each one, is an adventure in discovering southern Illinois. To take up Bill Horrell's book, in contrast, is an adventure of another sort. In stark black and white it introduces the viewer to the world of southern Illinois coal mining. Its images are not intended to please the senses as Trovillion's do. Horrell is the chronicler in images of those who dig coal, of the way they do it, the machinery they use and what they leave behind in the way of structures, equipment and the very shape of the land itself. It is Bill Horrell the sociologist as much as the photographer who dominates these pages. The way the miners are, the structure of their lives, the hazards they must deal with every working day — these are the concerns of the artist. Horrell's book, unlike Trovillion's, is neatly ordered. He moves from the faces and persons of miners, to deep mining, to work in narrow seams ("low coal"), to the people on top of the earth who make it all go, to surface or strip mining, and logically last, to what is left behind when the mines close. His book has two strengths lacking in Trovillion's. His son, Jeffrey L. Horrell, who is librarian of the Fine Arts Library at Harvard University, has contributed a foreword. From it the reader can learn much that is useful about the Horrell family and the motivations that lay behind his father's work. From the younger Horrell, for example, we learn that his father "preferred working in black and white for the stability and clarity of images" and that "he became interested in social documentaries after studying and looking at works of the Farm Security Administration project as background for his teaching." Bill Horrell did not learn until late in his life that two of his own early pieces of work were included in the FSA collection. Horrell's book also benefits from an introduction by Herbert K. Russell. Russell edited the book A Southern Illinois Album: Farm Security Administration Photographs, 1936-1943 (SIU Press, 1990), an experience that aligned his thinking with Horrell's on certain matters. He is also sufficiently well informed about coal mining to prepare the reader to better understand the pages of images that follow. That Jeffrey Horrell and Herbert Russell did their tasks so well is fortunate, for like Trovillion's book, the one to which they contributed has no running text to accompany its images, only brief captions. Trovillion has created a collection of colorful images of beautiful scenes. Horrell has given us a social documentary that is seldom pretty, never in color, but always powerful and compelling as a portrait of one of the key economic enterprises of the region. Taken together, these two books comprise a major step toward a better understanding of southern Illinois. David Kenney was born in Carbondale, Ill., in 1922 and lives There now in semi-retirement after serving as professor of political science at Southern Illinois University for many years. His books include Basic Illinois Government, Stratton of Illinois and Making a Modern Constitution.

Lincoln and the impulse toward tabloid history By DAVID E. LONG Michael Burlingame. The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994. Pp. 380 with introduction, a note on sources, appendix and index. $29.95 (cloth). In 1992, Michael Burlingame introduced himself at a conference of historians as a psychohistorian," employing a descriptive term that he then explained, tongue in cheek, was one word and not two. Some of those in attendance were unconvinced by the disclaimer. His first major publication, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, has done little to change the opinions of those skeptics. Psychobiographers are an odd subspecies of historian, seeking to explain not the importance of the message or even the messenger in influencing the course of history, 'but instead probing the nether world of the psychodynamics which compelled the messenger to act. Thus The Psychohistory Review is subtitled Studies of Motivation in History and Culture. Nearly a century and a third after Abraham Lincoln saved the Union, freed the slaves and championed democracy as no other figure of the 19th century, Burlingame wrests him from his sarcophagus and pins him to the analyst's couch in order to trash him for having a bad marriage, experiencing a midlife crisis and getting mad at incompetent generals who wasted the lives of young men in a profligate manner while gaining little toward ending the war or defeating the Confederates. We learn from Professor Burlingame that Lincoln freed the slaves because his father treated him like a slave, became first a highly successful circuit-riding lawyer and later president of the United States

July 1995/Illinois Issues/31

Summer Book Section because he was locked into a miserable marriage with an abusive spouse, and was vaulted by a midlife crisis from being a hack politician into becoming the greatest statesman in American history. This is tabloid history, reductive in scope and context, selectively focusing on sources and incidents that support the author's conclusions. Chapter Six, titled "Lincoln's Attitude toward Women: The Most Striking Contradiction of a Complex Character," begins with the sentence, "Abraham Lincoln did not like women." The chapter hardly supports the author's thesis, proving only that Lincoln was sometimes unsure of himself in the presence of particularly handsome women, a not uncommon affliction among men who like women too much. In the chapter on "Lincoln's Anger and Cruelty," Burlingame talks at length about the president's uncomfortable relationship with his temperamental secretary of the treasury, Salmon P. Chase. He cites Montgomery Blair, Lincoln's conservative postmaster general, who became the sacrificial lamb of an 1864 deal with the Radicals involving the withdrawal from the presidential race of third-party candidate John Charles Fremont. Blair said that Chase "was the only human being that I believe Lincoln actually hated." But despite an indictment of Chase's self-serving ambition, insufferable arrogance and "autocratic demand for complete control of his department's patronage," Burlingame never mentions the two incidents that most undermined the effectiveness of Lincoln's presidency and the success of his conduct of the war as commander-in-chief. The first was Chase's role as cabinet mole to the Radical Republicans in the Senate during the dark days of December 1862, and the other was his part in bringing about, or not preventing, the Pomeroy Circular (a pamphlet promoting Chase's candidacy and vilifying Lincoln as an ineffectual president) in early 1864. Chase's overweening ambition and nepotism in dispensing Treasury Department patronage were traits Lincoln could overlook; petulance that jeopardized the success of Union arms and cost the lives of Federal soldiers, he could not. The failure to mention these incidents in an account of the strained relations between the president and his treasury secretary leaves an incomplete picture of why Lincoln felt the anger that he did toward Salmon P. Chase. In another anecdote in the chapter on Lincoln's anger, Burlingame describes an incident which came "on the heels of Willie Lincoln's death in February 1862" when "a supplicant for a postmastership in Michigan loudly demanded to see the bereaved president." No event of Lincoln's adult life so bowed him emotionally as the death of this child. Nevertheless, he immersed himself in his work, and on the day in question when he emerged from his office to learn the source of the commotion, he agreed to meet with the office-seeker but asked the man if he did not see the crepe on the door and realize that somebody in the White House was dead. The intruder responded, "Yes, Mr. Lincoln, I did. But what I wanted to see you about was important." This incident caused Lincoln's anger with the man. If it is evidence of a volatile temper or a cruel streak, then there are few who would not be guilty of the sin. The most controversial chapter of the book has already drawn comments from David Letterman and Good Morning America and has resulted in a Springfield State Journal-Register editorial cartoon that has gained notoriety across the country. This chapter was described by historian Geoffrey C. Ward in American Heritage as "the definitive catalogue of anecdotes about Mary Lincoln's tumultuous personality, all aimed at demonstrating that Lincoln's home life was 'unbearable.'" Burlingame cites a volume of evidence in support of his claim that Mary Todd Lincoln was a shrew with a violent temper and that her hopelessly henpecked husband spent far longer riding the circuit than he had to in order to avoid his unhappy home. The last sentence of the chapter reads, "The Lincolns' marriage was ... a fountain of misery, but from it flowed incalculable good for the nation." In other words, if Abraham Lincoln had been happier at home he wouldn't have stayed away from there doing the professional and political things which got him elected president, and once in that office wouldn't have had the storehouse of wisdom and patience to draw upon which made him so successful. That is all very interesting, though most of it has been said before, but at one point Burlingame suggests "that Mary Lincoln may have been unfaithful." Abraham Lincoln was not only a henpecked and abused spouse, he was a cuckold as well. This entire paragraph is premised on some of the most unreliable sources imaginable. One is a letter from a reporter to David Goodman Croly, managing editor of the New York World, claiming that White House gardener John Watt told him in 1867 that "Mrs. Lincoln's relations with certain men were indecently improper." Much of what was "indecently improper" in the Victorian 19th century (when it was scandalous for a society matron to bare an ankle) would hardly qualify as such today. In addition, Watt was not a credible witness, having participated in 1861 as the principal in a scheme to defraud the government about expenditures made by Mrs. Lincoln, and later having threatened to blackmail her unless he was paid $20,000 hush money. Another of the sources cited in support of the suggestion of Mary Todd Lincoln's infidelity was Edward McManus, White House doorkeeper who was fired by the First Lady in January 1865 and a month later "apparently told Thurlow Weed that she was romantically linked with a man other than her husband." Might this witness have had a personal agenda other than bedrock truthtelling? A final piece of "evidence" was a letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Abram Wakeman, in which she supposedly says, "I have ... decided not to leave my husband while he is in the White House." Only by looking in the endnotes do we learn that no such letter exists, that the information was based on an account related by Wakeman's daughter (who supposedly saw the letter as a young girl) to her daughter, who provided the information for a story that appeared in the Newark Star in 1951, some 86 years later. But this is 1995, and the nation is currently in the midst of a mania occasioned by the trial of The People vs O.J. Simpson. Spouse abuse, adultery, mental instability and scandal among the rich and beautiful is much more interesting than saving the Union, freeing the slaves and preserving democratic government. The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln will do well, and the book does make for an interesting read. Unfortunately, its appeal will be the result of a conscious decision that it should travel the low road and emphasize what its author describes as the "dark side." David E. Long has been hired as a faculty member to teach Civil War and constitutional history at East Carolina University. He is author of The Jewel of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln's Re-election and the End of Slavery, which has been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. 32/July 1995/Illinois Issues |

|

|