|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By JENNIFER HALPERIN

An Illinois prisoner may have made your desk

and chair. And critics of correctional industries say that could cost you your job At a time when the state is just about out of room — and patience — for prisoners, Illinois Correctional Industries sounds like a great idea. It puts inmates to work sewing clothes, assembling furniture, recycling antifreeze, making cigarettes. Hundreds are at work every day learning a trade, learning good work habits, building confidence and earning money to pay part of their expenses. It sounds too good to be true. And for some people it is. For every prisoner making and selling products, critics say, a job is lost in the private sector. What's more, they contend prison industries have unfair competitive advantages over private businesses. They aren't required to pay minimum wage. They needn't carry workers compensation insurance. In many states, including Illinois, they get first dibs on filling state agency orders, so they essentially work under no-bid contracts. "It's an unfair competitive advantage," says Sue Perry, executive director of the Prison Industries Reform Alliance, or PIRA. The national group represents a number of business and labor organizations, including the National Association of Manufacturers, the United Food and Commercial Workers and the Carpenters Union. It lobbies against expanding prison industries in fields that compete with the private sector, such as furniture and garments. "I think what's happened is that as the state is forced to deal with a large number of prisoners, politicians are grabbing at anything and everything they can to try to reduce incarceration," says Shelley Hoffman, whose husband is part-owner of Wiley Office Equipment in Springfield. The business supplies desks, tables and other office furniture to state agencies. Illinois Correctional Industries makes a range of office furniture aimed at the same market. "Do I think prisoners should work? Yes," Hoffman says. "But as someone who has operated a business for 35 years, I don't think I should be disallowed to compete so prisoners can have a job. Somebody isn't asking the question: Who are they displacing?" Ron Parish says he wants to make sure such questions do get asked. As chief administrative officer for Illinois Correctional Industries, he acknowledges that expanding inmates' work opportunities is among his highest priorities. At the same time, he says, it's crucial to preserve jobs in the private sector. "How would you feel if your brother or sister were out of a job because an inmate was given one?" he asks rhetorically. "I

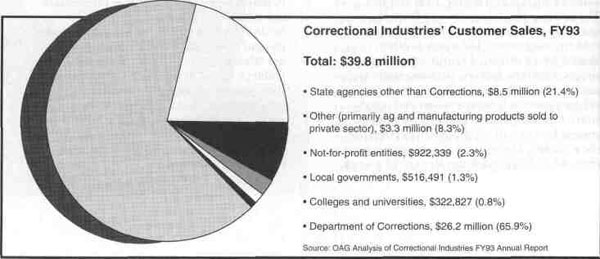

20/August 1995/Illinois Issues have to make sure we can answer to the constituents of this state — the taxpayers. I have lawmakers calling me with legitimate concerns about how prison industry affects businesses in their districts. It wouldn't do us any good to have taxpayers losing jobs." The concept of inmates working has been around since the early 1800s. At first efforts focused on hard manual labor, Parish says. "It was chain gangs and time spent breaking big rocks into little rocks. The idea was to tire the prisoners out." By the 1900s the focus shifted to encouraging inmates to do productive work. By the mid-1970s, when Illinois Correctional Industries was established, planners wanted prisoners to learn skills that could be transferred to the private sector. Instead of receiving an appropriation from the state legislature each year. Correctional Industries is supported by a revolving fund. Last year, the operation had revenues of nearly $40 million but a net loss of $1.5 million, which Parish hopes to make up next year. Now, Parish says, almost 2,000 of the nearly 40,000 inmates in Illinois state prisons perform a wide variety of jobs — from processing meat to silk screening. The positions are in high demand, so inmates must interview and perform well to keep them, Parish says. Prisoners farm more than 5,000 acres, harvesting and processing food to feed the state's booming inmate population. They sew their own uniforms and build much of their own furniture. More than 50 inmates who have become certified to do asbestos abatement have been hired by companies in Chicago. That sounds good. The problems begin when Correctional Industries supplies clothes, furniture and other products to state agencies that otherwise would buy from private manufacturers and suppliers. "It can be very frustrating," says John Young, an owner of Illini Supply Inc. in Decatur. He says prison industries aren't on a level playing field with the private sector. Some of the obvious advantages, he says, are that prisons don't have to pay property taxes or minimum wage salaries, and their original work sites and equipment are subsidized by the government. What's more, they may not always be able to provide products more cheaply than the private sector. Parish says he agrees — so much so that at times he has backed off on orders from such public agencies as school districts if private businesses were in danger of laying off employees. "It's a fine line that I have to walk. I want inmates to learn things that are going to help them once they get out. I think that means something to us as a society. We hope it keeps some from coming back." This hope is difficult to substantiate, though; the state does not keep recidivism statistics on inmates who work in Correctional Industries. So where do public officials draw the line between potential rehabilitation and guarding against job losses? Furniture -and garment-production operations are firmly in place in Illinois prisons. There is little chance of phasing them out, given the capital investment. But business and prison interests seem to agree on an answer for the future: moving prison industries away from products and services that compete with the private sector and toward labor-intensive jobs that private industry can't afford to do. Recycling is a possibility, say Perry and Parish. For example, the private sector can't afford to dismantle mattresses, which are made up of recyclable elements. It is cost-prohibitive to pay people minimum wage to separate and sell the parts, Perry explains, so they usually end up in landfills. Using prison labor would bring down the cost to the break-even point. Parish says prisoners now dismantle certain appliances and sell the parts for scrap metal. He says he'd like to go a step further: public-private ventures in which communities hire inmates to separate recyclables that otherwise would be landfill- bound. "Recycling ... wouldn't put people out of jobs," says Cindy Davis, who owns Resource One of Illinois, an office furniture supplier in Springfield. "Let them do things that don't compete with the private sector. I don't think they need to have glamorous jobs." *

August 1995/Illinois Issues/21

|

|

|