|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

November 1995 / Illinois Issues / 10 An analysis by MICHAEL HAWTHORNE State Sen. Walter Dudycz is shrewder than he's willing to admit when it comes to the volatile subject of affirmative action. The Chicago Republican ignited a fierce debate earlier this year when he introduced legislation to prohibit race and gender preferences in college admission and hiring policies and in contracting and hiring by state and local governments. He argues such preferences end up discriminating against whites. Although his proposal was sent to a subcommittee, the traditional legislative burial ground, hundreds of opponents crowded into hearings Dudycz held last summer in Chicago and Springfield. At the hearings, civil rights activists noted that whites continue to hold more than 80 percent of the jobs in two-thirds of the agencies, despite 20 years of affirmative action in state government. The director of the state Department of Human Rights said there is no preferential treatment given to unqualified minority job applicants. She cited statistics that suggest there isn't widespread discrimination against whites, who make up 78.4 percent of Illinois' population. Gov. Jim Edgar, meanwhile, said the state's affirmative action laws shouldn't be scrapped because they don't set specific requirements — or quotas — for minority participation in jobs and contracts. But for the media-savvy Dudycz, who also is a Chicago police detective, attacking affirmative action plays well in his largely white, middle-class Northwest Side district. He says he's expressing the frustration of many whites, including scores of his fellow white police officers, who believe racebased preference programs allow "unqualified" minority applicants to get jobs over "qualified" white candidates. Dudycz and others say affirmative action promotes "reverse discrimination." Although Dudycz' hearings seemed to lend more heat than light to the debate about racial and gender equity, he isn't worried. "Protest me," he had dared a Hispanic construction contractor earlier this year. "March in front of my [office]. I'll get more votes."

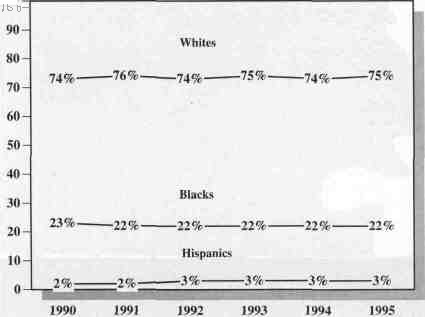

Playing with the politics of fear Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life by Charles Murray and the late Richard J. Hennstein. The analysis gave new currency to an old argument — that blacks are inherently less intelligent than whites — providing a foundation for those who argue that programs designed to overcome economic and social obstacles do little good in the long run. Now comes Dinesh D'Souza with The End of Racism: Principles for a Multiracial Society. More subtle than Murray and Hennstein, November 199 51 Illinois Issues/11 Figure 1. State job breakdown, 1990-1995

According to the secretary of state's office, the breakdown in state employment for whites, blacks and Hispanics has been stable for the past five years. D'Souza builds his case against race-specific remedies on moral and cultural grounds. He believes merit alone should determine career and social advancement. That principle might be achievable in a robust economy. When the government and corporate sectors went through a period of rapid expansion during the 1970s, affirmative action helped to open doors for talented and educated minorities by encouraging companies to hire nonwhites. In his 1979 book, The Declining Significance of Race, University of Chicago sociologist William Julius Wilson argued that "the very expansion of these sectors of the economy has kept racial friction over higher-paying corporate and government jobs to a minimum." Flash ahead to 1995. America is in the midst of dramatic corporate downsizing and wages are stagnant. Government forecasts predict the economy is on the rebound, but hardly a day goes by without an announcement that a major corporation is slashing its workforce, putting thousands on the unemployment line and leaving others wondering whether they'll also be left without a paycheck. "Affirmative action has become a scapegoat for the anxieties of the white middle class," writer Michael Kinsley noted earlier this year in The New Yorker. "Some of those anxieties are justified; some are self-indulgent fantasies. But the actual role of affirmative action in denying opportunities to white people is small compared with its role in the public imagination and the public debate." Economic insecurity has always given some politicians an opening to advance their careers. But civil rights activists fear decision-makers want to roll back whatever gains we've made in closing our racial divisions. California is setting the pace. Gov. Pete Wilson is a longtime moderate Republican who ardently supported affirmative action throughout most of his political career. But with defense plants closing and his state's economy on the skids, Wilson reversed course earlier this year and began waging an assault on race and gender preference programs, starting with admission to the University of California system. While the tactic couldn't save Wilson's erstwhile presidential campaign, there's no shortage of candidates willing to attack affirmative action. GOP presidential candidates Bob Dole and Phil Gramm both say they want to eliminate the policy.

The language of racial division Senate Republicans vow to produce a study that spotlights abuses. But Rose Mary Bombela, the director of the state agency responsible for monitoring compliance with affirmative action laws, says widespread "reverse discrimination" is a myth. Only 35 of the 902 discrimination complaints filed with the state Department of Human Rights during the past six years were filed by white males, Bombela says. Of those, only three were supported by substantial evidence. In the political world, though, perception often is more important than reality. Some analysts believe Republicans are in a position to benefit from that perception by using affirmative action as a "wedge" issue in appeals to voters disenchanted with the Democrats. Instead of advancing their own strategy on affirmative action, the Democrats have been forced to 12/November 1995/Illinois Issues defend the status quo and respond to a language of fear coined by the policy's detractors. Ironically, several historians credit a Democrat for being a harbinger of the current debate over affirmative action. Former Alabama Gov. George Wallace, infamous for his 1963 "Segregation forever!" inaugural address and his 1968 independent presidential bid, is the Godfather of racial code words that appeal to white anxieties about the progress of blacks. Taylor Branch, author of the civil rights history Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, highlighted the technique in a recent review of a Wallace biography: "Without harping on racial epithets, as everyone expected him to do, Wallace talked all around race by touching on the related fears of domination, coining new expressions such as 'forced busing' and 'big government,' which were anything but common cliches 30 years ago." More recent additions to the Wallace-inspired lexicon include "quotas" and "reverse discrimination." Race-based remedies Currently state officials seek 10 percent minority participation in building and road projects (5 percent for minority firms and 5 percent for those owned by women). Highway contracts also are reserved for minority-owned firms in the Chicago area. Though the results are mixed, there is no question that affirmative action has created opportunities that otherwise wouldn't be available to minorities. State Sen. Miguel del Valle, another Chicago Democrat, notes that while affirmative action is portrayed as only benefitting racial minorities, firms owned by white women have received substantial business through the state's preference programs. Yet, many conservative intellectuals — white and black — contend that race-based preference programs actually serve to block the progress of blacks as they emerge from decades of legalized segregation and other forms of racism. They attack the policies from a different angle, suggesting that affirmative action and welfare programs undermine black initiative. There are no such arguments about traditionally accepted forms of "affirmative action." Elite universities frequently seek geographical diversity by turning away better qualified New Englanders to admit a Midwestemer or the child of an alumnus. As Kinsley points out, veterans-preference programs violate the oft-stated principle that a job should go to the best qualified candidate. "Some veterans may have sacrificed nothing in particular, while nonveterans who have sacrificed greatly in other ways get no preference, or may even lose out to a less deserving veteran," Kinsley wrote in The New Yorker. "The point is not that giving veterans a preference is a bad idea — only that, like any group generalization, it is approximate. Yet we live with it." Charles Morris, vice chancellor for academic affairs at the Board of Regents, says Illinois has had a long history of preferential treatment at public universities. During the 1800s, he notes, state universities were open only to white children. Affirmative action has helped to erase decades of racial and gender discrimination, Morris says, but "equal opportunity in higher education for minorities and women remains a distant goal." The disparity is highlighted by employment figures from the state's flagship university. There were only 52 black and 44 Hispanic faculty members among the 1, 993 tenured or tenure-

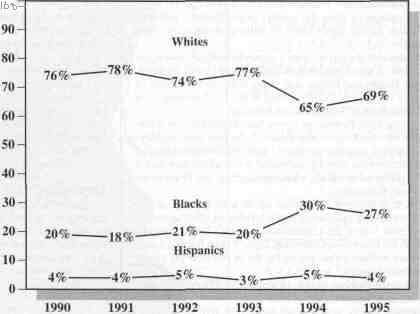

Figure 2. Breakdown of state hiring, 1990-1995

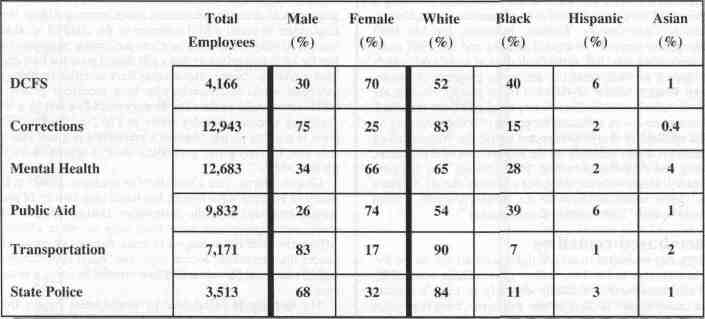

Breakdown of hiring in state government for whites and the two largest minority groups, according to data provided by the secretary of state. November 19951 Illinois Issues/13 Table 1. State agency employees by gender and race

The secretary of state's report for 1995 and the depiction of the categorization by gender and race within various Illinois state agencies. track professors at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign last fall. Because there is a shortage of black Ph.D.s graduating from the nation's major research universities, those figures aren't likely to improve much in the near future. Results also are mixed when it comes to hiring in state agencies. Some departments, such as Children and Family Services, Mental Health and Public Aid, boast high concentrations of minority employees. Yet 90 percent of the 7, 171 employees at the Department of Transportation are white. Theresa Faith Cummings knows how difficult it is to diversify the state work force. She used to be the only black employee at the state Abandoned Mined Lands Reclamation Council. Now she oversees minority recruitment and affirmative action for another predominantly white state agency: the Department of Natural Resources. The new department is made up of what used to be the Department of Conservation and a handful of other agencies. Fewer than 100 of the consolidated agency's 2, 000 full-time workers are minorities, Cummings says. "I'm trying to get people tested so their names are on the list of potential job candidates, but it's tough." Part of the problem used to be geography. Minorities generally live in urban areas, while much of the former conservation department's work was in rural areas. The new department, though, has entities in all 102 counties. "I think the lack of minority employees can be attributed to people in-house knowing other folks and letting them know about vacancies," says Cummings. "Those are the people who traditionally get jobs in this department." Like veterans-preference programs, hiring people based on their connections violates the principle that merit alone should determine who gets a job or contract. But many of the same politicians attacking affirmative action make no pretense about using their position to steer state jobs and business to campaign supporters. In fact, Illinois politicians have a long history of promoting patronage in jobs and contracts, despite court rulings intended to curb cronyism. Cummings is trying to change that. Backed by Brent Manning, the department's director, she constantly reminds office managers that they need to give minorities the same opportunities afforded to white job candidates. "It's hard to believe that coming over here from my old job is an improvement," she says. "It shows we've still got a long way to go."

Decoding the discourse By debating affirmative action, politicians could clarify what we as a society will and won't stand for. Such a debate also could be used to divide us further. Michael Hawthorne is Statehouse bureau chief of the Champaign- Urbana News-Gazette. 14/November 1995/Illinois Issues

|